In 2008, MESDA acquired a monumental, two-piece walnut Tennessee corner cupboard (Figure 1). With strong architectural appeal and distinctive carved elements, the cupboard exemplifies the highly competent level of cabinetmaking available on Tennessee’s frontier at the close of the eighteenth century and reflects the significant role that Scots-Irish craftsmen from the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia played in furnishing settlers and artisans to East Tennessee.

The corner cupboard is part of a distinctive group of furniture made for patrons who settled in and near Knox County, Tennessee, in the final decades of the eighteenth century. Coming primarily from Augusta, Botetourt, and Rockbridge counties in Virginia, many of the families established themselves in the fertile Grassy Valley, about five miles north of the town of Knoxville (Figure 2). Chief among them was the family of William Anderson (1758-1830), who at one time owned MESDA’s corner cupboard. William Anderson came from Rockbridge County, Virginia, and in 1801 settled in the Grassy Valley on the waters of Whites Creek. Along that very same creek, on a farm adjacent to the Anderson homestead, lived the cabinetmaker responsible for building the corner cupboard: Moses Crawford.

Like the Anderson family, Moses Crawford was a member of the Scots-Irish community. Although his arrival in Tennessee had occurred twenty-five years ahead of the Andersons, he too was from the Shenandoah Valley.[1] Crawford’s residence and possible training in the Shenandoah Valley is consistent with attributing the corner cupboard to his shop: The cupboard displays significant features which relate to furniture produced in the northern Shenandoah Valley. In particular, the cupboard’s arched cupboard doors, scrolled pediment, carved finial, tympanum shell, and carved rosettes (Figure 3) have been observed to relate to Frederick County, Virginia, work.[2] Many of those features also appear on case pieces produced in Augusta County, Virginia, where Moses Crawford was known to have lived earlier in his life (Figures 4 and 5).[3]

MESDA first documented the Moses Crawford corner cupboard in August 1981 during the museum’s field research in Tennessee. MESDA identified two additional pieces of furniture attributed to the same artisan: a glazed-door corner cupboard with a Knox County history (Figure 6) and a six-drawer chest of drawers, or bureau (Figure 7).

Of particular note, MESDA also recorded the ownership history of the Moses Crawford corner cupboard. It had been owned for nearly a century by the Truan family, Swiss immigrants to Knox County. According to the last Truan descendant to own the cupboard, it had been part of the household contents in 1849 when the Truans purchased William Anderson’s Grassy Valley farm and two-story log home from William’s son, Judge Robert McCampbell Anderson (1794-1855), and Robert’s wife, Catherine McCampbell.[4] The Anderson and McCampbell families, originally from Rockbridge County, Virginia, had settled in Knox County near the end of the eighteenth century and their two families had shared close kinships for centuries leading back to family origins in Ireland. Uncertainty whether the Crawford corner cupboard had come to Robert and Catherine Anderson through his family or hers resulted in it becoming known as the “Anderson-McCampbell” corner cupboard.

Until now, no investigation had been undertaken to determine the corner cupboard’s history predating ownership by Judge Robert McCampbell Anderson and his wife. This article will present late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth-century evidence for identifying the original owners of the cupboard and establish Moses Crawford as the maker of MESDA’s corner cupboard and seven other pieces of case furniture. In the process, Moses Crawford will be revealed to be Tennessee’s earliest documented cabinetmaker.

Knoxville and the Grassy Valley

The area where Knoxville would be established was first explored for settlement in the 1780s (Figure 8). James White (1747-1821), along with Alexander McMillan (1749-1837) and others, surveyed the area within the French Broad and Holston river watersheds after 1783. James White erected a fort along the Holston River in 1786 in what a year later would be laid out as Hawkins County, North Carolina. On 2 April 1790, the United States Congress accepted the cession of North Carolina’s western lands (present-day Tennessee), organized the region into the Southwest Territory, and established requirements necessary for its citizens to achieve entry into the Union as a state.[5]

William Blount (1749-1800) served as the territory’s first governor. He chose White’s settlement as the seat of government and named the new capital after United States Secretary of War Henry Knox (1750-1806).[6] Situated on a rise on the north bank of the Holston River, the town was just four miles below the mouth of the French Broad River and ideally located as a trade center for supplying goods to the Cherokee and Chickasaw Indian tribes.[7] [8] An observer arriving from Philadelphia in 1791 described the place as absent of houses “except shanties put up … to hold government stores.”[9] Despite that harsh criticism, substantial building was soon underway. Knox County claimed 11,573 inhabitants by 1795, a number that included 2,365 slaves.[10] By 1799, nearly a hundred houses, principally built from logs, had been erected in Knoxville.[11]

Settlement within the Grassy Valley, located just north of Knoxville between Black Oak and Webb’s ridges, occurred simultaneously with White’s endeavor. Veterans of the Revolutionary War began to clear the land for homesteads and apply for grants from North Carolina in payment for their service. Among the first in the valley was John Adair (1732-1827) and his wife, Ellen Crawford Adair (1734-c.1827). The couple established a station in the valley in 1788 on a 640-acre grant from North Carolina. The Adairs were from Northern Ireland. They arrived in America in 1771 and a few years afterward moved into the Watauga settlement of upper East Tennessee, where Adair would serve as entry-taker for Sullivan County beginning in 1777. Ten years later, once established in the Grassy Valley, Adair’s Station was designated as a depot from which the Cumberland Guard could obtain supplies for the escort of settlers making the treacherous journey from East Tennessee to the Middle Tennessee settlements located near Nashville along the Cumberland River.[12]

John Crawford

In 1790, John Crawford (1756-1831) began to register land grants along Whites Creek adjacent to Adair’s Station. John Crawford was a native of Augusta County, Virginia, and a veteran of the 1780 Battle of King’s Mountain, fighting for the American cause. It appears Crawford was already established in the Grassy Valley by 1790 and residing on the property for some time because that same year, on 3 November, he was commissioned as a captain in the Hawkins County militia. Grassy Valley was a part of Hawkins County at the time, as it was being reconstituted under territorial status by Governor Blount.[13]

The following year, another Crawford settled along Whites Creek. In December 1791, Samuel Crawford (1754-1822) recorded a grant for 200 acres on the headwaters of Whites Creek adjoining John Crawford’s holdings.[14] Like John, Samuel Crawford was a native of Augusta County, Virginia, and a veteran of the Revolution. Samuel Crawford is recorded in some family histories as having participated in the building of the first log house in Knoxville and his own home was a two-story structure similar in form to most in the Grassy Valley (Figure 9)—including the one constructed by John Crawford on his farm.

The precise relationship between John, Samuel, and the cabinetmaker Moses Crawford has not been fully established. The men were of Scots-Irish lineage due to their surname and continual proximity and interaction with acknowledged Scots-Irish families. Each of the Crawfords can be traced back to Augusta County, Virginia, and all arrived in Tennessee before 1780. Once in Tennessee, the three men lived near one another time and time again as they moved westward within the state. Considering their respective ages and the fact that families often settled close to one another during the period, some degree of kinship—possibly brothers—is almost certain.[15]

John Crawford was married in Augusta County, Virginia, to Jane Lauderdale, whose family were early settlers of the county. Their first child, Jane, was born in 1776. Crawford was present in Washington County (then part of North Carolina) by 1780 when he joined the Overmountain Men to march in the campaign against the British that ended with an American victory at King’s Mountain.[16] The war depleted the North Carolina treasury and in order to compensate its veterans a system was set up to grant lands from the western territory as payment for service in lieu of specie.

By obtaining land grants in the Grassy Valley in 1790, John Crawford’s intent could possibly have been to more permanently settle near a family member already in the area. That relative may have been John Adair’s wife, Ellen, a Crawford by birth and a native of Northern Ireland.[17] Regardless, John Crawford established himself as a significant landholder in the Grassy Valley. By 1797, he had accumulated nearly two thousand acres along Whites Creek. Crawford was a leader in the county militia, as previously mentioned, serving first as a captain in Hawkins County in 1790 and again later in the Knox County militia after that county’s creation two years later.[18] [19] A neighbor, George Christian, writing to the historian Lyman Draper in 1845, described John Crawford as:

an active officer, brave enough, though sometimes indiscreet. [He] was one of the first settlers of Knox County, stood all the brunt of the Indian wars in those days. About 1792 the upper towns were professing to be at peace, whilst the lower towns kept up constant war on our border settlement. There was sent for the use of the Indians to Knoxville a quantity of goods, whilst the frontiers were kept in continual alarm by the frequent murders and other aggressions by the Indians, so much so, that a strong party headed by Crawford proceeded to Knoxville, dragged out the goods designed for the Indians, piled them up on the streets, set fire to them all. All this was done under the eye of Captain Ricard. For a while this made a good deal of notice and noise, but the government suffered it to pass, and among the people Crawford got great applause, for they elected him to the legislature several times.[20]

John Crawford became a major in the Knox County regiment of the Tennessee militia on 4 October 1796. Earlier the same year he and John Adair had been elected as two of the four representatives of Knox County to attend a convention held in Knoxville to adopt a constitution for the newly formed state of Tennessee.[21] Crawford served as one of the two Knox County representatives in the state’s first General Assembly of 1796-97 and as senator in the third General Assembly, 1799-1801.[22]

1801 marked the last year that John Crawford’s presence is documented in Knox County. He had frequently served as a juror in the county court, but his last appearance in this role was 12 January 1801.[23] In the fall of that year, Crawford sold most of his Grassy Valley property, along with the two-story log house, to William Anderson and relocated his family to eastern Middle Tennessee on the Roaring River in Jackson County.[24]

The shear scale of Moses Crawford’s corner cupboard exhibited at MESDA, as well as its prominent architectural appearance, suggests it was made for someone of means who enjoyed a certain amount of community importance. The cupboard was most likely constructed between 1790 and 1800 and has a long history of ownership in the Grassy Valley of Knox County. John Crawford, long established in the valley and active in the militia, local court system, and state politics, is the prime candidate to be the cupboard’s first owner.

Sitting directly on the floor—as MESDA’s massive cupboard does—supports a conclusion that the cupboard may have been considered an integral part of the house interior. Robert McCampbell Anderson sold it along with his parent’s log house to the Truan family in 1849. Perhaps John Crawford did the same in 1801 when he sold his Grassy Valley farm to Robert’s father, William Anderson. Such a massive piece of furniture would have been difficult to move across rivers and over Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau; necessities if John Crawford had chosen to take the cupboard to his new home in Jackson County in 1801. Instead, it is most probable that John Crawford sold the cupboard along with his log house to William Anderson before moving west.

The Anderson-McCampbell Family

The family of William Anderson (1758-1830) had emigrated to the United States during the great Scots-Irish migration. His paternal grandparents and father Isaac Anderson (1730-1811) arrived in Augusta County, Virginia, about 1741. The family settled among the McCampbells, with whom they shared close friendships and familial ties that can be traced back to the Ulster province of Ireland.[25] William Anderson’s decision to relocate his family to East Tennessee may have been influenced by the presence of an extensive family network of relatives already present in the Grassy Valley.

Anderson arrived in Knox County in the fall of 1801 with a large family that required immediate housing and shelter from the approaching winter. The family included William’s wife, Agnes “Nancy” McCampbell (1757-1837); five sons (ranging in age from seven to twenty-one years old); two daughters (two and twelve years old); William’s father, Isaac Anderson (1730-1811); and at least two slaves.[26] John Crawford’s thousand-acre plantation along the waters of Whites Creek fulfilled Anderson’s needs precisely and the family purchased Crawford’s property, log house, and—most likely—the corner cupboard.[27]

Despite the “Anderson-McCampbell” label associated with the corner cupboard throughout most of the twentieth century—reflecting the cupboard’s ownership by Judge Robert McCampbell Anderson (1794-1855) and his wife Catherine McCampbell before its 1849 sale to the Truan family—an examination of Knox County records for Anderson and McCampbell family settlement dates within the Grassy Valley supports a conclusion that the cupboard descended through William Anderson to his son Robert rather than through Catherine’s McCampbell family. Although Catherine had paternal uncles who had settled in the Grassy Valley in the 1790s, her immediate family, including her father John McCampbell (1757-1853), did not arrive in the area until 1820.[28] Additionally, Catherine’s father died well beyond 1849, the year that the cupboard was sold to the Truans. These facts make it highly unlikely that the cupboard passed to Catherine through the McCampbells.

Judge Robert McCampbell Anderson and Catherine McCampbell married on 31 March 1825 in a ceremony performed by Robert’s oldest brother, Isaac Anderson (1782-1857), pastor of the New Providence Presbyterian Church at Maryville, Tennessee, located about twenty-five miles from the Grassy Valley.[29] Reverend Isaac Anderson was not the only son of William Anderson to achieve prominence in the Eastern Tennessee community. Two of Isaac’s brothers, William E. (1785-1841) and Samuel Anderson (1787-1859), studied the law, as did his younger brother Robert McCampbell Anderson, who became an attorney and in 1837 was appointed a judge in the newly established 12th Judicial District of Tennessee.

Robert McCampbell Anderson’s judicial appointment was to a district that did not contain Knox County, where Robert and Catherine were living at the Anderson family farm in the Grassy Valley. They relocated to the town of New Market, in adjacent Jefferson County. As a result, in 1849 Robert sold the Anderson family property, the log house—and the corner cupboard—to the Truan family.

The Truan Family

The Truan family immigrated to Knox County from the Canton of Vaud in the Lake Geneva region of Switzerland in 1849.[30] Like the Chavannes family, who had arrived in Tennessee the preceding year, the Truans were members of the Assemblee de Freres larges (Open Brethren), a group of Christians who had in 1824 eschewed the formality of the National Protestant Church of Switzerland for a simple worship model focused on Bible reading, prayer, and hymns sung without instrumental accompaniment. Settling chiefly in the Grassy Valley north of Knoxville, the “Swiss Colony” would become Knox County’s largest European ethnic group by 1850.[31]

The first Truan to own the Moses Crawford corner cupboard was Jean Jacques Truan (1790-1858). Widowed in 1836 with seven children, Jean Jacques remained in Switzerland until 1849 when he—along with sons J. David (1832-1915) and P. Louis (1815-1861), and P. Louis’s family—travelled to Tennessee to reunite with Jean Jacques’s daughter, Henrietta (1825-1896), who had settled in Knox County the preceding year.[32]

Arriving in Knox County on 4 July 1849, the Truans were reunited with Henrietta and her husband, Auguste Gouffon (1820-1887). They lodged within the crowded walls of the Gouffon’s one-room log house four miles north of Knoxville, which the Gouffons were then leasing from the Chavannes family. Five or six farms were then for sale in the Grassy Valley vicinity and Auguste Gouffon had been gathering information to purchase one, but absent the arrival and approval of the Truans he had not entered into a purchase contract. They would decide as a family to purchase the farm belonging to Robert McCampbell Anderson.

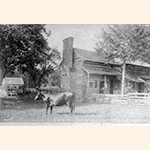

Jean Jacques Truan’s daughter-in-law, Louise Rochat Truan (1820-1865)—wife of Louis Truan—writing to her parents in July of 1849, described the new farm as the largest available in the community, consisting of 340 acres, and the purchase included the Anderson family’s house, a two-story log structure. At the suggestion of Auguste Gouffon, the family named the farm Ebenezer.”[33] A circa 1870 photograph made by Louise Rochat Truan’s son-in-law, Auguste J. Truan, is the only known image of the dwelling built by John Crawford and inhabited by the Anderson family before it was sold to the Truans (Figure 10).

The 1870 photograph shows a two-story log structure with a wooden shake roof and cut-stone chimney. The central doorway and flanking windows on the first floor suggest the hall-and-parlor plan for the interior, which Auguste Gouffon described in a letter to his parents dated 12 April 1852:

In looking at the house you see two windows, one above the other. The lower one is the one that lights the common room and where my father-in-law [Jean Jacques Truan] sleeps. The one above is that of my little family from where I write to you… . There is a third window at your left which is that of my brother-in-law, Louis [Truan]. Above the room of my brother-in-law there is another room which has a window at the side. Back of the house is the kitchen of which you can see a part at the left. The tree at the left is an acacia. At right are peach trees, the forge, and the garden.[34]

The Moses Crawford corner cupboard would have stood in one of the first floor rooms occupied by the Truans. In 1853, the year following his written description of Ebenezer, Auguste Gouffon began construction of a new house on the property where the Gouffons would take up residence separate from the Truans for the first time since 1849.[35]

Upon Jean Jacques’s death in 1858, Louis and Louise Rochat Truan remained in the log house that Louise described to her Swiss cousin, Henrietta in 1859:

We have a wooden house. The chimneys are made of stone. There are four rooms and a kitchen which is separated by a porch, and over the kitchen there is a storage room. I occupy one room, my sister-in-law one, my boys the third, and the other is the dining room. We have only the furniture that is necessary; chairs, table, bed and buffet. We find here all this is necessary to furnish a house nicely, but we have bought the least possible.[36]

Louise Truan’s use of the word “buffet” in her letter is significant. The French term buffet refers to a cupboard form. Though the word “buffet” appears in many different spelling corruptions in Tennessee inventories dating from the late-eighteenth century, most mid-nineteenth-century probate records use “corner cupboard” or simply “cupboard.” In fact, the term “cupboard” would be used six years later in the probate inventory for the estate of Louise Rochat Truan after she died of consumption in April 1865.[37] Her inventory itemized the following household furnishings, including “1 cupboard”:

1 press, 2 large tables

2 small tables

1 cupboard, and Table furniture

1 cooking stove and vessels

1 clock, 10 chairs

1 large rocking chair[38]

Louise Rochat Truan’s will, dated 23 March 1865, vested her son Henri Truan (1841-1907) with “the enjoyment of the stock, farming implements and furniture” and she directed that no sale of the property be made after her death.[39] Henri’s younger brother Auguste Truan (1842-1931) eventually took up residence in their parent’s log home where the cupboard remained until about 1900 when Auguste and his wife Eliza (1847-1933) removed it to their new home in Washington County, Tennessee.[40] Louise Truan Campbell obtained possession of the corner cupboard when her mother Eliza died in 1933 and Louise retained ownership until the she sold the cupboard at public auction in 1946 or 1947.[41]

Moses Crawford

Attribution of MESDA’s corner cupboard (Fig. 1) to Moses Crawford (c.1743-1819) could not have been made without establishing a more complete provenance for the object. To summarize: the cupboard was most likely made for John Crawford in the 1790s, who then probably sold it with his property and log house to William Anderson in 1801; the cupboard would then have passed on with the house to William Anderson’s son, Judge Robert McCampbell Anderson; Judge Anderson then sold it among the household contents of the log house in 1849 to the Truan family; the cupboard then descended in the Truan family until it was sold at auction in the late 1940s. (See Appendix A for a timeline of the cupboard’s history and Appendix B for a timeline of Crawford’s life.)

Interestingly, the fact that John Crawford—most likely a close relative of the cabinetmaker Moses Crawford—is the best candidate to be the cupboard’s original owner is not the linchpin for unraveling the mystery. The strongest and most tangible connection between Moses Crawford and the corner cupboard is Moses Crawford himself: he is buried in the McCampbell family cemetery, within a mile of the site of the log house where the corner cupboard stood for over a hundred years. The cemetery, located on the southern edge of the Grassy Valley just southeast of Sharps Gap, is also less than a half-mile from the site of John Adair’s Station and situated on property owned by John Crawford before 1794. Moses Crawford is buried alongside his wife Rachel and other family members. Simple limestone markers erected by a descendant without birth or death dates mark the graves.[42]

Like many artisans, Moses Crawford’s trade was not revealed in the historical record until he died. The probate inventory of his estate itemized cabinetmaking tools, a workbench, a glue pot, various planes, chisels, punches, and gouges, as well as walnut plank.[43] When viewed in total, Crawford’s inventory establishes him as a maker of furniture. A small quantity of carpenter’s tools suggests he may also have been a builder of houses.

Documents first reveal Moses Crawford as a resident of the Grassy Valley in 1800 when he purchased land that had once been owned by John Crawford; however, circumstances point to his being in the area for some time earlier (the specifics of which will be discussed more fully later in this section).[44] He had most likely followed John Crawford and Samuel Crawford in the early 1790s from the Nolichucky River Valley to Whites Creek in the Grassy Valley, just as they probably had earlier followed him from Augusta County, Virginia, to upper East Tennessee before 1780.

Moses Crawford’s connections to the Shenandoah Valley also support his attribution as the cupboard’s maker. As mentioned at the beginning of this article, MESDA’s corner cupboard is stylistically related to Shenandoah Valley furniture, especially pieces made in Frederick and Augusta counties. Moses Crawford, like John Crawford and Samuel Crawford, can be traced back to Augusta County, Virginia. In May 1764, Augusta County resident George Skillem brought suit against “Moses Crofford,” but evidence presented before the court indicated the defendant had “gone to Carolina” (present-day upper East Tennessee was considered the western territory of North Carolina until the 1780s).[45] A return of summons in June found “no inhabitant” at Crawford’s home.[46]

He was probably among the settlers who first began to make their way during the 1760s into the valleys of upper East Tennessee, within the watersheds of the Watauga and Nolichucky rivers. Settlement of the region was in violation of a 1763 royal proclamation prohibiting British colonials from settling west of a line drawn through the Appalachian Mountain chain.[47] Nevertheless, people came. The area east of the Tennessee River’s confluence with the Ohio, covering present-day Kentucky and Tennessee, was controlled by the Cherokee, and the first European settlers of upper East Tennessee arranged leases with the tribe for entry onto Indian lands.

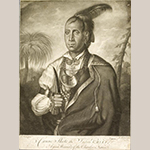

In March 1775, some 1,200 Cherokee gathered at Sycamore Shoals on the Watauga River to discuss the sale of their land. The Cherokee were represented by several chiefs, including Attakullakulla and Cunne Shote (Figure 11), who was also known as Occonostota (Figure 12).[48] The meeting had been orchestrated by Richard Henderson (1734-1785), a North Carolina jurist who had spent much of the 1760s promoting proposals to settle these lands. On 14 March, after four days of negotiation, an agreement was reached whereby Henderson’s Transylvania Company purchased approximately 20 million acres from the Cherokee. The conveyance included much of Kentucky and Middle Tennessee north of the Cumberland River as well as a small amount of territory extending to the Watauga settlement (near present-day Elizabethton, Tennessee).[49]

Settlers already living in the Nolichucky and Watauga River valleys also formalized their own land treaties with the Cherokee. On 25 March 1775, Jacob Brown (1736-1785), a blacksmith and Indian trader, secured two deeds for tracts in the Nolichucky River Valley.[50] Brown’s deed was signed by five of the Overhill Cherokee leaders, including Attakullakulla and Occonostota (Cunne Shote).[51] Witnessing the Cherokee signatures were two of Brown’s neighbors, Moses Crawford and Samuel Crawford (Figure 13).[52] The 1775 deed provides the earliest documentation for any cabinetmaker within the political boundaries now recognized as the state of Tennessee.

Once Jacob Brown held title, his neighbors sought deeds from him. On 18 April 1776, Moses Crawford acquired from Brown a deed to 182 acres along the north side of the Nolichucky River, for which Crawford paid £100. That tract was in turn sold by Moses Crawford to Michael Woods on 1 September 1777, for the sum of £200.[53] The appearance of Moses Crawford and Samuel Crawford on the deed from the Cherokee to Brown two years earlier is strong indication that both Crawfords were already living along the Nolichucky and that Moses may have been residing on the land acquired in the deed from Brown.

Shortly afterward, in November 1777, the North Carolina legislature organized the region into Washington County, North Carolina—the first time that North Carolina officially organized its territory west of the Appalachian Mountain chain.[54] Two deeds recorded after Washington County was formed assist in more precisely locating Moses Crawford’s home during this period. On 26 February 1778, Isaac McConnell and Thomas Blackburn each entered two-hundred-acre claims for land in Washington County on Richland Creek, beginning “at the mouth of a big spring about a mile above Moses Crawford’s land.”[55] Crawford’s proximity to Richland Creek is further confirmed in a 6 November 1779 land entry made by Colonel John Sevier (1745-1815), who would become Tennessee’s first state governor in 1796. Sevier’s entry for 640 acres on Richland Creek included “Moses Crofford’s” improvement on the north side of the Nolichucky.[56]A second entry, made the same date for land also along the north side of the Nolichucky River, included the improvement of a “James Crawford.”[57] Whether or not these two Crawford men (Moses and James) were kin, their proximity to one another, as well as events occurring in the late summer and autumn of 1780, would prove troublesome to Moses Crawford.

A climate of fear and anxiety gripped the settlers of upper East Tennessee as early as August 1776 when the American South became actively involved in the American Revolution at the Ninety-Six settlements in Upcountry South Carolina. Loyalist and patriot were pitted against one another, a fact evidenced on 24 February 1779 when three witnesses appeared before the Washington County court and gave sworn testimony sufficient to convince the tribunal that Moses Crawford remained loyal to the crown and was thus of concern for the local colonials. The court heard the testimony—the specifics of which were not preserved in the minutes—without Crawford being present. In his absence, and without having heard any defense, the judges ordered Crawford “to the Goal for further trial.”[58]

Shortly thereafter, Moses Crawford appeared before the court with counsel and the justices rescinded their earlier order of jailing him upon the condition that Crawford take an oath of allegiance to the State of North Carolina and post a bond of ten thousand pounds.[59] If Crawford agreed, he would remain free; his refusal would ensure that he would wait out the war incarcerated at Salisbury, North Carolina. Crawford took the oath and remained of “peaceable and good behavior” during the remainder of the Revolution.[60] Whether or not Crawford had loyalist leanings is uncertain. In the end, proof of his allegiance to the crown was insufficient to declare him a Tory threat. Whatever his political opinion, he benefited from sufficient local friendships: Seven of his neighbors joined in his bond as sureties.

In the fall of 1780, the upper East Tennessee settlements became directly involved in the patriot revolt. Buttressed with a resounding victory in August over American forces at Camden, South Carolina, Lt. General Earl Charles Cornwallis (1738-1805) ordered Major Patrick Ferguson (1744-1780) to take his force from the Ninety-Six settlement in South Carolina and cross over into North Carolina, protecting Cornwallis’s troops on the rear and western flanks.[61] Once in North Carolina, Ferguson encamped at Gilbert Town (present-day Rutherfordton) and, having heard that the Wataugan settlers were expected to join the resistance, sent word to leaders there that “if they did not desist from their opposition to the British arms, he would march his army over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay their country waste with fire and sword.”[62] Major Ferguson’s threat prompted militia leaders Colonel John Sevier and Colonel Isaac Shelby (1750-1826) to call for volunteers to engage Ferguson.

Over a thousand men gathered at Sycamore Shoals on 25 September 1780, forming a militia that became known as the Overmountain Men. Whether Moses Crawford was among the volunteers is unknown, but James Crawford, Moses’s neighbor on Richland Creek, did join. Two days into the march, James Crawford slipped away from the patriot force and sent word to Ferguson of the Tennessean’s movements.[63] Based on James Crawford’s actions in 1780, it might be possible that the loyalist accusations lodged against Moses Crawford in 1779 were in fact a case of mistaken identity. Despite James Crawford’s treachery, the Overmountain Men pursued Ferguson as he moved his army from Gilbert Town and ultimately fought the British at King’s Mountain, where the patriots were victorious and Major Ferguson was killed.[64]

There is no surviving documentation for Moses Crawford from 1784 until 1800. He probably remained on Richland Creek until shortly before 1790 when he most likely followed John Crawford and Samuel Crawford to the Grassy Valley in 1790 or 1791.

The first evidence for Moses Crawford in Knox County is a 4 December 1800 deed confirming Crawford’s purchase of a 290-acre tract on Whites Creek.[65] He purchased the land from Thomas Cox of Grainger County, which Cox had previously purchased in October 1794 from John Crawford.[66] In 1790, Cox had been appointed a lieutenant in the Hawkins County militia—the same date John Crawford was commissioned as captain in the same unit. In April 1794, William Blount’s secretary noted that Cox had left the regiment, a strong indicator that Cox was not expecting to remain in Knox County.[67] Moses Crawford may have already been living on the land he purchased from Cox, and Cox—a subordinate to John Crawford in the local militia—may have been called upon by a superior officer to “hold” the property until such time as Moses could purchase it outright.

Minutes for the Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions of Knox County reveal Moses Crawford was regularly called to duty as a juror beginning in January 1802, a date that followed John Crawford’s relocation to Jackson County in Middle Tennessee. Joining Moses Crawford as a potential juror that day was his Grassy Valley neighbor and possible relation, Samuel Crawford. That Moses Crawford appears to have replaced John Crawford in the county court further supports a conclusion the two men were kin to one another and that one family member was being substituted for another to fulfill a community duty. Moses Crawford was a regular participant on the county court until the fall of 1818.[68]

Moses and Rachel Crawford were parents to at least four children who, along with some grandchildren, are also buried in the McCampbell family cemetery. The oldest child, Margaret “Peggy” was born in 1774 and married Solomon George (1757-1830) on 12 September 1803 in Knox County.[69] Solomon George was born in an area of Augusta County, Virginia, that was organized into Botetourt County in 1770. He arrived in Knox County about 1792 from Orange County, North Carolina, and Margaret Crawford may have been his second wife.[70] According to her tombstone, Margaret died 6 November 1827. The Crawford’s second child was Elizabeth “Betsy” Crawford (1785-1866).[71] She outlived all of her siblings.

Joseph Crawford (1789-1865) is the only known son of Moses and Rachel Crawford. A family Bible records Joseph’s date of birth as 9 January 1789.[72] Like his sister Betsy, Joseph claimed in both the 1850 and 1860 census to have been born in North Carolina, an accurate statement considering that present-day upper East Tennessee was considered the western territory of North Carolina at the time of their births. Joseph married Nancy Davis (1782-1859) on 5 September 1809 in Knox County and they had nine children.[73] No direct evidence of Joseph’s participation in the cabinet trade has been discovered—although as a child and possibly young adult he almost certainly would have been required to work in his father’s shop in some capacity—and Joseph did not purchase any property at his father’s estate auction. Census information suggests he was a successful farmer.[74]

The birth date of Moses and Rachel Crawford’s fourth child, Rebecca Crawford, is unknown. She married John Milton Clark in Knox County on 29 July 1820, so was likely born sometime in the 1790s and was probably the youngest of the Crawford siblings. She is buried next to her mother and her tombstone is inscribed “Rebecca Clark.”

Moses Crawford died in late 1819 and his probate inventory was taken on 28 December by his youngest daughter, Rebecca. The inventory was recorded in the April 1820 term of court. Movable furniture listed in his household included: three pair of walnut bedsteads; one small pine chest and one trunk; one cupboard and contents; two walnut tables; two looking glasses; one dozen chairs; and a pine table. The walnut bedsteads and tables in his household furniture may reflect Crawford’s preference for the wood, a sentiment also expressed in the body of work attributed to his shop.[75]

In the inventory of Crawford’s shop, his daughter recorded “one set of cabinetmaker’s tools”; a few carpenter’s tools and some plain stocks; one small grindstone; two candlesticks; eleven books; “several pieces of dry beech fit for plain stocks”; and one workbench with a screw and iron vice, glue pot, various planes, chisels, punches, and gouges. Crawford also had 190 feet of walnut plank on hand, a possible indication that he was still constructing furniture shortly before his death.[76]

Personal property belonging to Moses Crawford was sold at public auction on 13 January 1820 and brought just over $500.[77] The majority of his shop tools and stock were purchased by Andrew C. Hall (1798-1858). Crawford’s death occurred when Hall would have been 21 years old, and it is possible (but not documented) that he was apprenticed to Crawford (see Appendix C).

Moses Crawford’s daughter Betsy Crawford spent a cumulative $128.44 to purchase nearly all the household furnishings and kitchen equipment as well as first choice of three of the family sheep, a cow with bell, a yearling heifer, and some farming tools. She was the largest single purchaser at her father’s estate sale. Moses’s widow, Rachel, spent $4.00 for “one bed and furniture.” Their combined purchases would make up a newly constituted mother-daughter household where daughter Rebecca continued to live until her marriage to John Milton Clark in July later that year.

Rachel Crawford survived to be recorded in the 1830 Federal Census, the earliest existing for Knox County. Noted as the head of household and classified as between the age of 80 and 90 years, Rachel Crawford was living with her second-eldest daughter, Betsy, and “one free white male” aged 20 to 29 years, probably her grandson Samuel S. C. George (1807-1863).[78]

Furniture Attributed to Moses Crawford

Seven cupboards, including MESDA’s example (Fig. 1), have been identified and attributed to Moses Crawford.[79] Five of the seven will be discussed and compared in this article, as will a desk and bookcase, tall chest, and a chest of drawers (or bureau).

Significantly, the collective histories of Crawford’s surviving furniture represent ownership traceable to Scots-Irish families who established themselves in Knox and Blount counties between the years 1787 and 1801.[80] Not only do the provenances establish that the furniture was being made in the area where Moses Crawford’s shop was located during the period, but they also culturally connect Crawford to the Scots-Irish community in East Tennessee.

The most complex and visually striking of the Crawford corner cupboards is the walnut example most likely made for John Crawford in the Grassy Valley and now exhibited in the MESDA collection (Fig. 1). Constructed between 1790 and 1800, this cupboard is the only one surviving known from the Crawford shop to use a scrolled pediment and incorporate carved elements, here floral rosettes, a gadrooned tympanum shell, and central flame and urn finial (Fig. 3).[81] Additionally, the cupboard breaks from the other examples in its two-part case construction and its lack of shaped ogee feet—it rests directly on the floor. Despite these differences, many features present on this cupboard serve as a catalogue of Crawford shop traits and characteristics.

Both the upper and lower case doors of the cupboard are hung by surface mounted brass hinges. Notably, the spines of the hinges are carefully placed in alignment with a bead molding applied to the surround edge of the cupboard opening (Figure 14). Like all cupboards attributed to Moses Crawford, the edges of all door rails and stiles are molded and the rails are through-tenoned into the stiles (Figure 15). Door panels tend to be roughly finished of thick stock, necessitating the need to cut dados into the interior surface to allow the doors to close and rest against the shelves, which are generally about an inch in thickness (Figure 16). On this cupboard, the upper surface of the shelves is cut with a groove to accommodate the display of plates.

The drawers, which are set at the waist of the cupboard, are finished in a cockbead and employ brass rosette bails as hardware (Figure 17). The case stile dividing the drawers, including the exposed joinery, is consistent with Crawford’s usual method of installing this component. Drawer sides are yellow pine and joined by heavy dovetails covered by the cockbead at the front and open dovetailed and reverse pinned at the rear (Figures 18 and 19). Some of the dovetails are wedged. Drawer bottoms are tulip poplar. The drawers are stopped by the case back. The proper left drawer exhibits construction marks visible on the interior drawer surfaces, details that are seen in the same place on all the cupboard drawers discussed in this article (Figure 20). The deep rails separating the doors from the drawers are also observed in all Crawford shop cupboards.

The upper and lower cases have fluted quarter columns finished with similarly turned capitals and bases. A plain, turned area about an inch long serves as a neck separating the fluting from both capital and base. Of note is the cabinetmaker’s rounding off of the outside edge of the plinth joining the capital and base, a characteristic habit observed in Crawford’s other surviving furniture (Figure 21). This feature is not observed on other Knox County furniture associated with the Delaware Valley tradition, and it is also absent on Shenandoah Valley work frequently associated with the Knox County groups. A substantial base molding finishes the lower edge of the cupboard and its profile is very similar to base molds of the single-case cupboards constructed in the Crawford shop.

The low pitch of the heavily denticulated scrolled pediment and the large carved rosettes were likely inspired by architectural images available in the late 1750s when Crawford would have been of apprenticeship age. In particular, the pediment of a doorway found at Plate XXVI of William Salmon’s Palladio Londinensis published in 1738 may have served as a model (Figure 22). The large rosettes shown over the doorway flank a central plinth emerging from a small tympanum board similar to that produced by Crawford on the cupboard. Also notable are similarities between the radius of the curves engaging the central plinth on the cupboard and this area shown on the doorway.

Perhaps the earliest surviving form recognized as a product of the Crawford shop is a walnut desk and bookcase (Figure 23) that descended in the family of Barclay McGhee (1759-1819), who arrived in Tennessee with his wife Jane McClanahan (1767-1835) from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 1787.[82] Shortly after their arrival, the McGhees settled in present-day Blount County, near Maryville, which was still part of Knox County prior to 1795. Barclay McGhee was a merchant and successful land speculator, accumulating thousands of acres of land, primarily in the Little Tennessee River Valley. McGhee’s business and land speculating endeavors would have certainly required a desk and bookcase for proper record keeping.[83] About 1790, he constructed a two-story frame house on the main road leading from Knoxville to Maryville and probably acquired the desk and bookcase from Moses Crawford at this time.[84] In 1793 and 1794, McGhee placed advertisements in the Knoxville Gazette requesting customers to settle their accounts and he maintained an active business relationship with the Indian Agency at Knoxville.[85]

The composite five-part cornice is a standard feature repeated on most corner cupboards associated with the Crawford shop. Cornice construction on the bookcase (Figure 24) includes a shaped astragal glued directly to the case across the frieze above the doors and returning along the sides.[86] The bookcase doors are unusual in both construction and appearance. The rectangular doorframes are evenly divided by a central rail that is through-tenoned into the stiles and secured by large exposed pins in the same fashion as the top and bottom door rails. The two vertical openings created within the frame are covered by shaped boards having molded outer edges that recall similar shaped panels seen on tall case clock bases from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. This treatment has not been documented in other Tennessee case furniture. The cupboard opening has an applied bead mold like that seen on MESDA’s corner cupboard (Fig. 1).

The front edge of the bookcase is ornamented with fluted quarter-columns that have an arched stop approximately two-thirds the height of the lower door panel. The base and capital turnings are nearly identical to those seen on MESDA’s cupboard and the other large cupboards attributed to the Crawford shop. Notable also is the presence of a small stop-molding inserted just above the capital and below the base plinth of the quarter-columns (Figure 25). This is actually a triangular-shaped block that is molded on the two visible sides. A triangular-shaped stop-molding is a feature also present on a secretary and a tall chest of drawers that are attributed to the vicinity of Winchester, Virginia (Figures 26 and 27).[87]

The interior arrangement of the desk, with its stepped two-over-one arrangement of drawers with blocked fronts flanking a central prospect, is unique in documented Tennessee work, and has much more in common with designs fashionable in the 1770s than the early 1790s when this desk and bookcase was likely constructed for McGhee (Figure 28). The desk interior’s design is in keeping with work that Crawford would have been exposed to early in his cabinetmaking career. The arched central prospect with carved keystone and flanking fluted Doric pillars—like the MESDA corner cupboard’s pediment—suggest Crawford’s likely exposure to eighteenth-century architectural designs.

The desk’s fallboard features an applied panel with an outer edge shaped in an astragal, repeating the treatment seen on the bookcase frieze (Figure 29). Small candle drawers flank the top drawer of the desk section. These drawers also support the fallboard when the desk is open. The faces of both candle drawers are finished with an applied circular, gadroon-carved applique that is more typically associated with work from Pennsylvania and the North Carolina Piedmont showing Delaware Valley influences. The vertical divider separating the candle drawers from the top-most drawer of the desk is open dovetailed into the lock and drawer rails in the same fashion as between the waist drawers of the larger cupboards from the Crawford shop. All drawers are finished with a cockbead and the front edge of the desk is chamfered, fluted, and stopped with an arched head. Most likely, the desk was originally raised on ogee feet—the present turned feet and straight edged molding are replacements.

A walnut cupboard (Figure 30) is likely contemporary in date with the McGhee desk and bookcase.[88] The cupboard has remained in the same family since being acquired in the early-twentieth century in Maryville, but its specific history prior to that is not known. The cupboard incorporates the same cornice treatment present on the McGhee bookcase and it is possible that it may have been acquired by Barclay McGhee for use in his Maryville home. Ancestors of the present owners purchased property from a direct descendant of Barclay McGhee near the turn of the twentieth century.[89]

Five separate elements make up this cupboard’s cornice construction (Figure 31). The carved astragal is set flush against the frieze and abutting the lower edge of the molded board immediately above. The method of laying out the astragal is visible in the form of compass point indentations centered on a scribe line (Figure 32). The full-height quarter columns flank the case storage areas and are finished with an arched head stop-flute positioned about mid-drawer level (Figure 33). Capital and base turnings also conform closely with those present on the bookcase section of the McGhee desk and bookcase.

The doors originally hung on face-mounted H hinges but are now supported by replacement butt hinges hung on the case stiles, attached in such a way that only the spine of the hinge is visible. The doors and drawers, which maintain their original bails, are constructed in the same manner as those of the MESDA cupboard. The drawers slide directly on the top surface of the board used to close the lower cabinet space. The vertical stile separating the cockbeaded drawers is shared by other Crawford shop furniture. The dimensions of the substantial rails above and below the drawer compartment are consistent in all cupboards identified with the Crawford shop (Figure 34).

The cupboard’s front case stiles and returns, together with the case backboards, extend to the floor to support the cupboard, alleviating stress on the swelled ogee feet that are attached to underlying case components (Figure 35). This method of construction is similar to that seen on the Augusta County, Virginia, tall chest of drawers (Fig. 4) and no doubt figured heavily in the survival of the original feet on this corner cupboard. Large wooden pins exposed on the case surface are used to join the various elements of the cupboard.

Shelves in the upper cabinet are ploughed, creating a groove for plate display and this feature is executed in the same manner as seen on the MESDA cupboard (Fig. 1) and the glazed-door corner cupboard (Fig. 6), which is also constructed of walnut and nearly identical in format with the exception that it features glazed upper doors in place of the double panel doors present in the remaining examples. The replacement feet seen on the glazed-door cupboard closely resemble the original ogees surviving on the cupboard illustrated in Figure 30, but are somewhat smaller in scale.

A cherry cupboard (Figure 36) descended in an eastern Knox County family.[90] The cupboard is of smaller stature than most examples from the Crawford shop and further varies with the use of fielded panels in the doors, a surrounding architrave molding, single waist drawer, and frieze inlay. Simple bracket feet appear in place of ogees. The overall visual effect is a decidedly architectural appearance and may suggest the cabinetmaker’s attempt to relate the cupboard aesthetics to a specific household interior.

Like all cupboards associated with the Crawford shop, this cupboard features fluted quarter columns that extend nearly the full height of the piece. The turned capital and base elements, which are identical to one another, do not have a plain transitional turn separating them from the fluting as seen on the larger cupboards (Figure 37). The interior edges of all doors are molded in the same profile seen on the remainder of the examples studied. The upper and lower panels of the upper doors are separated by a relatively wide rail and pins used in joining the components are exposed (Figure 38). The single drawer set at the cupboard waist is lipped on three sides and tulip poplar is used as a secondary wood for the drawer in contrast to yellow pine that appears elsewhere in the cupboard. Notable is the installation of a brass tea table latch as hardware closure for the lower cabinet (Figure 39).

The two uppermost elements of the cornice are restorations and are likely smaller in scale than the missing originals. The remainder of the cornice below the restored cove molding is original and consists of a shaped dentil capped with decorative drillings, which rests above a board having a molded lower edge that transitions into a running astragal. The crisp edge of the astragal component contrasts with the beveled edge treatment seen on Crawford’s larger cupboards. Compass point and horizontal scribe marks needed for laying out the pattern for cutting the astragal are visible, as in the other examples.

A sawn oak fret in a Wall of Troy pattern inset into the cupboard frieze with flanking hearts is the only known use of decorative inlay associated with the shop. The yellow pine backboards extend to the floor and rise above the board used to ceil the upper cupboard to the height of the cornice, creating a well.

A small walnut cupboard descended in the Coulter family of Blount County (Figure 40). Like its parent Knox County, Blount County had begun to be settled in earnest shortly after 1783. Coulters were present in Knox County before its formation as indicated in John Coulter’s advertisement in the Knoxville Gazette of 6 June 1793 in which he warned readers not to trade on a 1790 bond to Benjamin Goodwin that had been paid but not surrendered. Another family member, Alexander Coulter, began acquiring property along the Holston River in 1797.[91]

Richard Coulter III (born 1765 and died before 1830) and his wife Elizabeth Stephens (1769-1841) were probably the first to own the cupboard, which then descended for five generations in their family. Richard was part of a family migration that included his siblings and father, who left Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, to settle newly opened lands in Wilkes County, Georgia, about 1786. While in Georgia, he married Elizabeth Stephens. About 1797, the same year Alexander Coulter was acquiring land along the Holston River in Knox County, Richard and Elizabeth relocated to Blount County, Tennessee.[92]

The Coulter cupboard displays a number of subtle shifts in decorative treatment that signal Crawford’s attempt to adapt to a lighter neoclassical taste; changes which may have resulted from exposure to the work of other artisans then appearing in Knoxville. The cornice is constructed of four component pieces rather than the five seen on the shop’s larger cupboards (Figure 41). While the cornice continues to robustly extend beyond the surface plane of the case, as in Crawford’s earlier work, the top most element above the ogee is integral with the ogee and replaces the two-part, quarter-round-over-cove treatment seen in the remainder of the group. This ogee is nailed over a thin board, the final inch of which is exposed and sawn into a dentil. The dentil board in turn rests over a thicker board, the lower edge of which is molded and affixed to the lower-most decorative element, which is the astragal running across the frieze. Here the astragal is produced from a very thin stock that, rather than abutting the molded board above, actually extends about an inch behind the board.

Thin door stiles and rails together with a simple chamfer in place of the usual fluted quarter-column combine for a lighter aesthetic. The astragal surround of the lower doors recalls the applied shaped panel used to decorate the fallboard of the McGhee desk (Fig. 23).[93] In keeping with this lighter, neoclassical aesthetic, the spurs have been eliminated from the returns of the swelled ogee feet (Figure 42)—which are in other respects constructed as those found on Crawford’s larger cupboard (Fig. 30)—and the case pinning is noticeably smaller than that exhibited on the larger cupboards. That last feature could indicate the presence of a younger, more delicate, hand within the shop.[94]

Drawer joinery is consistent with the remainder of the cupboards (Figure 43), including the presence of construction marks visible on the interior sides of the proper left drawer noted on all the larger two-drawer cupboard examples (Figure 44). Unlike the larger cupboards, this cupboard’s drawers do not slide directly on the top side of the board ceiling the lower cupboard but instead rest on front-to-back square rails that are face nailed to the top board of the lower cupboard from the interior (Figure 45). Also like the larger examples, the backboards rise above the top board of the case and rest on the floor to support the piece. All secondary components are of yellow pine.

Two forms of chests of drawers have been documented, a small two-over-four-drawer example (Fig. 7) and a tall chest (Figure 46). Both of the pieces are constructed of walnut. The smaller chest of drawers, more commonly referred to as a bureau at the time of its manufacture, primarily uses yellow pine as the secondary wood, but a small amount of tulip poplar is noted.[95] This mixture is commonly observed in cabinetwork attributed to Knox and its surrounding counties.

At the time the bureau (Fig. 7) was acquired near Nashville in the 1930s, its provenance was not obtained, but it is without doubt a product of the Crawford shop.[96] The top and bottom boards of the case are open dovetailed to the sides and this joinery is covered by the cornice and base moldings respectively. Quarter-columns are fluted without stops, as in the MESDA cupboard, and the capital and base turnings are similar to those seen on the furniture previously discussed. The cornice is made up of three elements seen on the shop’s larger cupboards (Figure 47), omitting the dentil and the molded board to which it would be applied. As seen on the large cupboards, the astragal board is glued to the case and does not extend behind the cove molding applied above, which on this piece is finished with a bead along the lower edge. The divider between the bureau’s two top drawers is joined to the case with an exposed dovetail, as seen on other Crawford furniture, and the original swelled ogee feet that survive on the front are notably similar to the feet of the corner cupboard illustrated in Fig. 30.

The surviving cornice elements of the tall chest of drawers (Fig. 46) suggest it was finished with a five-part cornice system like those seen on cupboards from the shop. Like the McGhee bookcase (Fig. 23) the case corners have a stop-mold above and below the fluted quarter-columns, which have an arched stop (Figures 48 and 49). Capital and base turnings are consistent with the group, but where the neck abuts the fluting the cabinetmaker has carved small arches to visually end the fluting in a more academic manner. This treatment has not been documented on any other piece from the Crawford shop. Drawer construction is consistent with the smaller bureau and again the uppermost case drawer divider is joined to the case with exposed dovetails. Both chests of drawers have framed drawer support systems that are dadoed and pinned to the case sides.

Conclusion

Moses Crawford’s appearance at Sycamore Shoals in 1775 represents the earliest documentation of a cabinetmaker within Tennessee, over two decades before the state entered the union. His 1764 presence in Augusta County, Virginia, associates him with Shenandoah Valley cabinetmaking traditions that were then carried further south and west as settlements crept gradually toward Tennessee.

Many of those early Tennessee settlers were Scots-Irish, as was Moses Crawford himself. The closeness and strength of the Scots-Irish communities in the Nolichucky River Valley, Grassy Valley, and greater Knox County are highlighted by Moses Crawford’s probable relationship with John and Samuel Crawford, his burial in the McCampbell family cemetery, and the families who purchased his furniture. Fittingly, it was Crawford’s physical proximity to the two-story log house in which MESDA’s corner cupboard stood for a hundred years—and the people who owned that house—that provided the key to identifying him as the craftsman responsible for making the earliest identified group of Tennessee furniture.

C. Tracey Parks is an independent scholar living in Lebanon, Tennessee. He served as the editor of The Art and Mystery of Tennessee Furniture and Its Makers Through 1850 by Derita Coleman Williams and Nathan Harsh. He can be reached at [email protected].

Appendix A: MESDA’s Moses Crawford Corner Cupboard Timeline

|

1790 |

John Crawford applied for land grants and subsequently built a two-story log house on Whites Creek in the Grassy Valley, located in what would become Knox County, TN |

|

1790-1800 |

Moses Crawford made the corner cupboard, most likely for John Crawford’s log house on Whites Creek |

|

1800 |

Moses Crawford documented for the first time in the Grassy Valley, purchasing 290-acres of land on Whites Creek |

|

1801 |

John Crawford moved to Jackson County, TN, and sold his Grassy Valley land and log house—and probably the corner cupboard—to William Anderson |

|

1819 |

Moses Crawford died and was buried in the McCampbell Family Cemetery about a mile from the Crawford-Anderson log house |

|

1830 |

William Anderson died and his son and daughter-in-law, Robert McCampbell Anderson and Catherine McCampbell Anderson, inherited the land, log house, and corner cupboard |

|

1849 |

Robert McCampbell Anderson while residing in Jefferson County, TN, sells his Knox County land, the log house, and the corner cupboard to Jean Jacques Truan |

|

1858 |

Jean Jacques Truan died and the log house and corner cupboard are bequeathed to his son and daughter-in-law, Louis Truan and Louise Rochat Truan |

|

1859 |

Louse Rochat Truan described a “buffet”—the corner cupboard—in a letter to her cousin |

|

1861 |

Louis Truan died |

|

1865 |

Louise Rochat Truan died and her inventory included “1 cupboard”; all of her property and furniture was willed to her son, Henry Truan |

|

1870-1900 |

Henry Truan’s younger brother, Auguste Truan, lived in the log house with the corner cupboard |

|

1900 |

Auguste Truan and his wife, Eliza Truan, move to Washington County, TN, taking the corner cupboard with them to their new home |

|

1903 |

On 18 November, the Crawford-Anderson-Truan house is destroyed by fire |

|

1931 |

Auguste Truan died |

|

1933 |

Eliza Truan died and her daughter, Louise Truan Campbell, inherited the corner cupboard |

|

1946-1947 |

Louise Truan Campbell sold the corner cupboard at public auction; the cupboard was purchased by Knoxville attorney Beverly Burbage |

|

2008 |

MESDA acquired the corner cupboard |

Appendix B: Moses Crawford Timeline

|

c. 1743 |

Moses Crawford born |

|

c. 1745 |

Future wife Rachel born |

|

1764 |

Probably moved from Augusta County, VA, to settle in the Watauga Settlement of present-day East Tennessee |

|

1764 |

“Moses Crofford” sued by George Skillem in Augusta County, VA |

|

1774 |

Daughter Margaret “Peggy” Crawford born |

|

1775 |

Witnessed a deed (along with Samuel Crawford) between Jacob Brown and Cherokee leaders for land in the Nolichucky River Valley of East Tennessee |

|

1776 |

Acquired a deed from Jacob Brown for 182 acres of land along the north side of the Nolichucky River for £100 |

|

1777 |

Sold the 182 acres of land to Michael Woods for £200 |

|

1778 |

Crawford was identified as owning land about a mile below the mouth of a big spring on Richland Creek, which flows southward into the Nolichucky River |

|

1779 |

A land entry by John Sevier identified “Moses Crofford’s” land on the north side of the Nolichucky; a separate document recorded the land of a “James Crawford” also located on the north side of the Nolichucky River |

|

1779 |

Three witnesses testified before the court that Moses Crawford remained loyal to the crown and was thus of concern for the local colonials |

|

1779 |

Crawford retained the services of attorney Luke Bowyer; Bowyer petitioned the court to rescind its order to jail Crawford and the court agreed with the conditions that Crawford take an oath of allegiance to the State of North Carolina and post a bond of ten thousand pounds |

|

1783 |

Crawford’s land was identified in a deed entered by Benjamin Ray for land on Richland Creek |

|

1785 |

Daughter Elizabeth “Betsy” Crawford born in present-day Tennessee |

|

1789 |

Son Joseph Crawford born in present-day Tennessee |

|

c. 1790 |

Most likely followed John and Samuel Crawford to Whites Creek in the Grassy Valley, in what is now Knox County, TN |

|

1790-1800 |

Made the corner cupboard, most likely for John Crawford’s log house on Whites Creek |

|

c. 1795 |

Daughter Rebecca Crawford born |

|

1800 |

Purchased 290-acres of land on Whites Creek from Thomas Cox (land that Cox had previously purchased from John Crawford in 1794) |

|

1802 |

Served as a juror in Knox County court for the first time (he was recorded as performing this duty regularly in Knox County until the autumn of 1818) |

|

1803 |

Daughter Margaret “Peggy” Crawford was married in Knox County to Solomon George of Augusta County, VA |

|

1809 |

Son Joseph Crawford married Nancy Davis in Knox County |

|

1817 |

Sued along with Adam Huntsman as security for Ambrose Jones; Crawford paid $31.60 |

|

1819 |

Moses Crawford died and was buried in the McCampbell Family Cemetery about a mile from the Crawford-Anderson log house |

|

1819 |

Crawford’s probate inventory—taken by his daughter Rebecca in December and recorded by the court in April 1820—itemized cabinetmaking tools, a workbench, a glue pot, various planes, chisels, punches, and gouges, as well as walnut plank |

|

1820 |

Property sold at public auction and brought just over $500; most of Crawford’s shop tools and stock were purchased by cabinetmaker Andrew C. Hall |

|

1820 |

Daughter Rebecca Crawford married John Milton Clark in Knox County |

|

1827 |

Daughter Margaret “Peggy” Crawford George died |

|

c.1835 |

Widow Rachel Crawford died |

|

1865 |

Son Joseph Crawford died |

|

1866 |

Daughter Elizabeth “Betsy” Crawford died |

Andrew C. Hall was the ninth child of born to Thomas (1758-1833) and Nancy May Hays Hall (1760-1836), who were married in Orange County, North Carolina, on 25 September 1783, following Thomas’s release from a British prison in Charleston. The family settled in Knox County, Tennessee, about 1796 on a land grant Thomas received for his military service in the Continental Army. Andrew was the first child born to the family on the new farm in Tennessee, which was located on the southern perimeter of Hines Valley, about three miles north of Moses Crawford’s farm on Whites Creek (Figure 50).[97]

Andrew C. Hall spent a total of $32.83 2/3 at Moses Crawford’s estate sale, purchasing the following: twelve walnut plank, one plank and some dry beech, three saws, two rabbet planes, a lot of cabinet maker tools, a set of chisels and gouges, one plow plane and two bits, one workbench and vice and a lot of chisels and punches. It is likely Hall also bought the remaining shop lumber, listed as “100 feet of walnut plank,” but the purchase was erroneously entered by the court clerk as being bought by Betsy Crawford. This entry appears at the end of the second page of the inventory recorded in the court minute book. Hall’s first purchase is recorded at the top of the next page where his name is misspelled “Andrew C. Mott.” Hall is the only purchaser at the sale having a distinguishing middle initial and his cumulative purchases entered by the clerk fall short of the total if the plank is not included in his purchases.[98] Additionally, the surname “Mott” does not appear in contemporary Knox County documents.

Hall’s purchase of cabinetmaking tools, plank, and a workbench clearly evidence both the young man’s vocation as well as his intent to practice the craft. Based on his birth year, Hall would have begun an apprenticeship in 1812, the year he turned fourteen, and completed his training on his 21st birthday in October of 1819. Considering the relatively short distance between Hall’s family home and that of Moses Crawford, it is possible that Hall could have learned the craft from Crawford, but no record exists to prove this relationship. Apprenticeships recorded in the public record involved contracts between the county court, and artisan, and an orphan. No public records were kept of the private apprenticeship contracts between the parents of young men like Hall and the masters with whom the parents entrusted their sons.

Hall lived his entire life in Knox County. He married Martha Jane Hansard (1806-1860) in May of 1821 and constructed a house next to her parents along Bull Run Creek, a few miles northeast of his own family homestead. Martha’s parents, William (1763-1846) and Martha Christian Hansard arrived in Knox County in 1806 from Amherst County, Virginia, where they had married in 1792. Martha was born shortly after their arrival.[99]

Outside the purchases Hall made at the Crawford sale, some additional evidence points to his involvement in the furniture trade. The 1840 Federal Census reported two persons employed in manufacturing or trade as members of the Andrew C. Hall household. Martha Jane Hall had a younger brother, Robert Christian Hansard (1810-1876), who was eleven years old when Andrew married into the family. Robert Christian Hansard’s pursuit of the furniture making business is confirmed in an 1844 advertisement in which he identified himself as a cabinetmaker in the nearby town of Tazewell.[100] Considering the family relationship it seems likely that Robert Hansard learned the trade from his older brother-in-law. Andrew C. Hall may have drifted away from the craft over the course of his life. He described himself as a farmer in the 1850 Federal Census.

[1] The author acknowledges with appreciation the assistance and encouragement of the following persons: Gary Albert, David and Marty Black, Dan Brown, Andrew Brunk, David Duggin, Robert Leath, June Lucas, Peggy Nickell, Kim Jackson Parks, Clifford Quinton, Sumpter Priddy III, Wes Stewart, and the private owners of the furniture discussed in this article.

[2] See examination report of John Bivins, 8 August 1981, MESDA research file (hereafter MRF) 11,228. For a discussion of the Frederick County, Virginia, furniture see Wallace Gusler, “The Furniture of Winchester, Virginia,” in American Furniture (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone Foundation, 1997), 228-265. See also Anne S. McPherson, “Adaptation and Reinterpretation: The Transfer of Furniture Styles from Philadelphia to Winchester to Tennessee,” in American Furniture (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone Foundation, 1997), 298-334. McPherson discussed four objects included in this study; the McGhee family desk and bookcase (illustrated as Fig. 23 in this article), MESDA’s corner cupboard (Fig. 1), the glazed-door corner cupboard (Fig. 6), and the chest of drawers (Fig. 7); she also discussed other furniture produced in Knox County, Tennessee, by other as-yet unidentified artisans working in the Delaware Valley style.

[3] The backboard of the clock (Fig. 5) extends nearly to the floor to support the case, a trait shared by the corner cupboards discussed in this article. See Ronald Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Southern Furniture 1680-1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection (New York: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and Harry M. Abrams, 1997), fig. 169, p 558.

[4] See MESDA MRF 11,228.

[5] Walter T. Durham, Before Tennessee: The Southwest Territory 1790-1796 (Piney Flats, TN: Rocky Mount Historical Association, 1990).

[6] Ibid.

[7] For the purposes of this article, the Holston River is considered to be the section of the Tennessee River from the mouth of the French Broad River (about four miles upstream from Knoxville) to the mouth of the Little Tennessee River (about 51 miles downstream). This definition of the Holston River is consistent with its designation prior to the establishment of the Tennessee Valley Authority in 1933.

[8] A description of the new town and observation of its potential as a repository for goods to supply the various Indian tribes appeared in the 11 February 1792 issue of the Knoxville Gazette.

[9] History of Tennessee from the Earliest Time to the Present; Together with an Historical and Biographical Sketch of the County of Knox and the City of Knoxville, Besides a Valuable Fund of Notes, Original Observations, Reminiscences, Etc., Etc. (Nashville, TN: Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1887), 839-840.

[10] Ibid, 807.

[11] On 11 July 1795, the boundaries of Knox County were reduced by the organization of Blount County, south of Knoxville. Knox County was further reduced by the establishment Grainger County 22 April 1796, and of Anderson and Roane counties in 1801.

[12] The site of Adair’s Station is memorialized by a Tennessee Historical Commission marker within the modern-day boundaries of Fountain City, Tennessee. The marker is a short distance from the burial site of John and Ellen Adair. John Adair was one of five commissioners appointed by the Knox County Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions “for the purpose of letting the building of a court-house, prison, and stocks, for said county.” Knoxville Gazette, 9 March 1793. See also, Nannie Lee Hicks, The John Adair Section of Knox County, Tennessee (Knoxville, TN: J.K.L. Lithographers, 1976), 1-16.

[13] The Blount Journal: 1790-1796 (Nashville: Tennessee Historical Commission, 1955), 37. This edition is a facsimile of the manuscript authenticated by Territorial Secretary Daniel Smith (1748-1818) and owned by the Tennessee Historical Society. The original journal was written by Daniel Smith, who spelled Crawford’s name as “Crafford.”

[14] Knox County Deed Book 8, p. 247, Register of Deeds, Knox County Courthouse, Knoxville, TN.

[15] A 23 November 1804 note in the amount of $25.00 against Samuel Crawford was part of the probate estate of Moses Crawford. Knox County Wills and Inventories Book 3, p. 180, Knox County Courthouse, Knoxville, TN..

[16] Katherine Keogh White, The King’s Mountain Men: The Story of The Battle with Sketches of the American Soldiers Who Took Part (Dayton, VA: Katherine Keogh White, 1924; Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Printing Co., 1977), 164.

[17] Hicks, The John Adair Section of Knox County, 12.

[18] Blount Journal, 37, 62.

[19] Also in 1792, he recorded his stock mark in the Knox County Brands Book as an “under Keill off each ear, and a split in the right ear, Brand thus, C [followed by a forward slash symbol with two parallel horizontal lines through it].” Brands Book, Register of Deeds, Knox County Courthouse, Knoxville, TN.

[20] White, King’s Mountain Men, 164.

[21] The other Knox County representatives were James White and his son-in-law Charles McClung, residents of Knoxville. Thus the Grassy Valley and Knoxville settlements furnished equal representation of Knox County at the state convention.

[22] For reference to Crawford’s senate service, see Tennessee Senators, Historical Listing, Anderson County – Wilson County, p. 129 (available online: http://www.tennessee.gov/tsla/history/misc/tga-senate2.pdf [accessed 21 December 2013]).

[23] Knox County Court Minute Book 3, p. 11, Knox County Courthouse, Knoxville, TN.

[24] On 14 December 1801, the first county court for Jackson County met in the home of Crawford’s son-in-law, John Bowen. John Crawford remained active in political matters following his relocation to Jackson County. In 1806 the new county was subdivided and its eastern portion, including the Crawford and Bowen homes, became part of Overton County. Crawford was elected to the 7th, 8th and 9th state assemblies serving from 1807 to 1813. Vernon Roddy, The Early Local Points of Non-Indian Administration and the Early Local Non-Indian Administrators of the Jackson County, Tennessee Area 1799-1810: A First Look” (TN: Vernon Roddy, 1983). See also, Robert M. McBride and Dan M. Robison, Biographical Directory of the Tennessee General Assembly Volume I 1796-1861 (Nashville: Tennessee State Library and Archives and Tennessee Historical Commission, 1975), 171-172. The authors included entries for two men named John Crawford and do not include the correct lifespan of the John Crawford (1756-1831) discussed herein.

[25] Samuel Tyndale Wilson, Isaac Anderson: Founder and First President of Maryville College, (Maryville, TN: Kindred of Dr. Anderson, 1932), 18-20, 38.

[26] For the Anderson family genealogy see MRF 11,228. William Anderson freed his “Black man Moses” in his last will and testament, written 4 April 1828. Anderson had two black polls in the 1806 tax record for Knox County indicating two adult male slaves.

[27] Knox County Deed Book A, p. 275. The deed is dated 4 October 1801 and the acreage conveyed to Anderson was made up from three grants made to Crawford: grant number 83 and part of grant number 102 registered in Hawkins County, together with part of grant number 286 registered in Knox County.

[28] The Knox County settlement dates for Andrew McCampbell (1754-1825) and his brother William McCampbell (c.1765-1813) are 1793 and 1796 respectively and are recorded on markers placed in the McCampbell Family Cemetery by descendants. Catherine’s father, John McCampbell, also served as an elder in the Presbyterian Church in Knoxville; see William S. Speer, Sketches of Prominent Tennesseans Containing Biographies and Records of Many of the Families who have Attained Prominence in Tennessee, (Nashville, TN: Albert B. Tavel, 1888), 398.

[29] Reverend Anderson had previously been installed as pastor of the Washington Presbyterian Church in Knox County in 1802—the same year as his marriage to Flora McCampbell (1782-1852)—when he built a log house two miles from that of his parents in the Grassy Valley. He was appointed pastor to New Providence Presbyterian Church in 1812 and relocated to Maryville (Blount County), where he established the Western Theological Seminary in 1819. He would serve as both pastor at New Providence and president of the seminary for the remainder of his life. Rev. John J. Robinson, Memoir of Rev. Isaac Anderson, D.D. (Knoxville, TN: J. Addison Rayl, 1860), 9-40, 161 and Will A. McTeer, History of New Providence Presbyterian Church Maryville, Tennessee 1786-1921 (Maryville, TN: New Providence Church, 1921), 4, 98.

[30] David Babelay, They Trusted and Were Delivered: The French-Swiss of Knoxville, Tennessee (Knoxville, TN: Vaud-Tennessee Publisher, 1988), 190.