Editor’s Note: This is the first installment of a two-part article presenting new research into the life and furniture of the cabinetmaker Porter Clay. The companion article, Porter Clay, “A Very Excellent Cabinetmaker”—Part Two: Associated Furniture, authored by Macklin Cox, will be published by the MESDA Journal in 2016.

Among Kentucky’s earliest and finest cabinetmakers was Porter Clay, brother of one of America’s foremost statesmen, Henry Clay.[1] Henry Clay is said to have declared of his brother, “He was the greatest man I ever knew.”[2] And, in an 1844 speech to the cabinetmakers of Columbia, South Carolina, Clay made a point of asserting that his brother was “once a very excellent Cabinet Maker.”[3] While Henry Clay devoted his life to a long and conspicuous career in national politics, one in which he attained lasting fame, his sibling Porter Clay led a mercurial existence. Brother to a United States senator, half-brother to an army general, and brother-in-law to Kentucky’s first millionaire, Porter Clay (Figures 1 and 2) began his adult life with great promise as a socially well-connected and talented artisan in Lexington, Kentucky. But after a diversely episodic career he met a melancholy and improvident end, removed from his family, and relegated to an unmarked grave on the early western frontier.[4]

Porter Clay was born in 1779 in Hanover County, Virginia, also the birthplace of his famous brother. He was the youngest son of the Reverend John Clay and his wife, Elizabeth Hudson Clay. John Clay was a Baptist minister during the colonial period when the Anglican Church was the established church. A rebel by temperament, for a time he was imprisoned for his zealous preaching and demands for religious freedom.[5] Reverend Clay was a farmer as well, and a prosperous one, moving in the mid-1770s to the farm that had belonged to his father-in-law, a tract of over 460 acres worked by twenty-one slaves.[6] Of the couple’s nine children, only three lived to adulthood, their sons John, Henry, and Porter.

When Reverend Clay died in 1781, Porter was only two years old. The following year, Elizabeth Hudson Clay married Captain Henry Watkins—whose brother, John Hudson, was married to Elizabeth’s sister, Mary Hudson Watkins. Porter Clay’s new uncle, John Watkins, moved from the Hanover County area into the district of Kentucky in far western Virginia prior to the soon-to-be commonwealth’s statehood in 1792. There, John Watkins was one of the founders of the town of Versailles, nearby to Lexington. He was a delegate to Kentucky’s constitutional convention and then a representative in the first legislature. In 1791, Henry Watkins and his wife Elizabeth determined to move west into Kentucky, as well.

At the time of the family’s removal, Henry Watkins was the legal guardian for his two minor stepsons, Porter and Henry Clay.[7] Elizabeth’s eldest son, John Clay, also moved to Kentucky with his mother, stepfather, and brother Porter, and opened a store in Lexington. Henry Clay (Figure 3), however, remained in Virginia, where Henry Watkins arranged for him to work in Richmond under Peter Tinsley, Clerk of the High Court of Chancery. From there Henry Clay became the amanuensis of Chancellor George Wythe, one of the most prominent and significant legal figures in Virginia—Wythe had been the first professor of law at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg and mentor to Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. After working under Wythe, Clay studied law with Virginia’s attorney general and former governor Robert Brooke. Clay received his Virginia law license on 6 November 1797 and moved west to Kentucky in the same month. He was licensed to practice law in Kentucky by March of the following year.[8]

Meanwhile, John and Elizabeth Watkins settled in the town of Versailles, where they opened a tavern adjacent to the courthouse square, on South Main Street. The Watkins Tavern, the town’s only tavern and in the center of the community, became a noted site of hospitality in recently formed Woodford County. The large masonry building was constructed of native stone by the stonemason Thomas Metcalf, who later served as governor of Kentucky from 1828 to 1832.[9]

Just as Henry Watkins arranged for the mentoring of his stepson Henry Clay by Peter Tinsley in Virginia, he arranged for Porter Clay to learn a trade soon after the family’s arrival in Kentucky. Porter Clay was apprenticed to a Lexington cabinetmaker, Thomas Whitney, in order to master the art and mystery of making furniture. Thomas Whitney was an Irish immigrant who appeared in the Kentucky district of Virginia as early as August 1789, when he married in Bourbon County.[10]

If Porter Clay was bound to serve a typical seven-year apprenticeship, he would have moved from Versailles to Lexington in 1792, at the age of thirteen, to begin his training in Thomas Whitney’s shop. The location of that shop in 1792 is not know, but in June 1797 Whitney acquired a lot at the corner of Main and Mulberry (later named Limestone) streets, and it is possible that he had rented this space prior to buying it. Lexington memoirist William A. Leavy noted that in 1804 “two houses, residence and shop of Thomas Whitney, one of the earliest cabinet makers” were located at the northeast corner of Limestone and Main streets. Whitney appeared as a cabinetmaker on Main Street in Lexington’s first city directory in 1806; he appeared again in the second city directory of 1818, the year before his death.

Whitney was evidently a prosperous and prominent figure in Lexington. He was a trustee of the town and frequently served as a court-appointed appraiser for various estates. He was also active in the Episcopal Church and his son attended Transylvania University. At the time of his death, Whitney owned six slaves.[11] Whitney’s location at the intersection of Limestone (the busy north-south Maysville Road corridor) and Main streets conspicuously placed his shop at the most active crossroads in the town. Given Whitney’s obvious commercial, social, and political status, Porter Clay should have benefited substantially from his association with him.

If the terms of his agreement with Whitney followed a traditional model, Clay would have remained bound to his master until he was twenty-one years old. However, on 5 March 1798, in what was probably the final year of his apprenticeship, Porter Clay and another apprentice, Colin Carters, rebelled against Thomas Whitney and absconded. Stewart’s Kentucky Herald of 6 March 1798 carried a notice posted by Thomas Whitney:

Thirty Dollars Reward

Ran away from the subscriber on the 5th inst. two apprentices in the cabinet-making business; one named Porter Clay… . Clay is about 20 years of age, about 5 feet 10 inches high, fair hair, and fair complexion, heavy limb’d and knock-kneed; took with him one blue coat and one black, one pair of pea-green breeches, and a pair of stripped [sic] overalls.

Whitney repeatedly ran the advertisement from March into mid-July, but received no claim for his offer of thirty dollars. Although Porter Clay had decamped from Whitney’s shop, he nevertheless felt an obligation toward his mentor: he arranged for his older brother, the attorney Henry Clay, to negotiate an ample financial settlement with Whitney to compensate him for the loss of an apprentice for one year.[12]

After leaving Whitney’s shop, Porter Clay left both Lexington and Kentucky. In a reversal of the prevailing westward movement, he set out for the northeast and for the island of Manhattan. There, for a year, he worked in the context of the foremost figures in the field of American furniture of the Federal period. One scholar of American decorative arts wrote: “Leadership in the design and production of furniture moved from Philadelphia to New York during the Federal period.”[13] A consciousness of this trend was shown even among New Yorkers of the time. Daniel Longworth, writing in 1805, noted that “this curious and useful mechanical art is brought to a very great perfection in this city. The furniture daily offered for sale equals, in point of elegance, any ever imported from Europe, and is scarcely equaled in any other city in America.”[14] As a journeyman in several shops in New York, Porter Clay would have seen the most sophisticated designs and materials and learned the techniques of construction then most in use. While he might later be regarded as a provincial craftsman, Clay had in fact been exposed to the best furniture that the nation could offer in forms, materials, and execution.

We know that Porter Clay returned to Lexington, Kentucky by the spring of 1799 because his name appeared there in a ledger entry of 16 April buying nails.[15] The purchase occured on the ledger sheet of his brother, John Clay, at the store of Thomas Hart, a nail manufacturer and one of the town’s wealthiest citizens. Only five days before, their brother Henry Clay had married Thomas Hart’s daughter, Lucretia. And Hart, like the Clay brothers, was a native of Hanover County, Virginia. Following his marriage to Lucretia Hart, Henry Clay built a new house on Mill Street approximately one hundred feet south of the Hart residence, which was at the northwest corner of Mill and Second streets.[16]

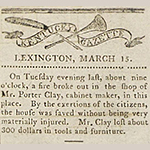

For his new house, Henry Clay required furniture, and he turned to his brother Porter to provide it. In Henry Clay’s early Lexington account book, almost a whole page is devoted to furniture bespoke from Porter Clay (Figure 4). The entry appears to date from 1804 or earlier and included the following items, priced in pounds, shillings, and pence:

one Side board 27-0-0

eighteen chairs & 2 setees 17-8-0

pair of Card Tables 15-0-0

Toilette table ___ ___ $3 2-18-0

Tester for Bed Stead 3$ 0-18-0

6 window frames for Curtains 7-11-6

Knife box 0-6-0

Plank for window Shutter 0-10-6

Tea table 7-10-0

Bed stead 5-8-0

Work on Book Case 1-1-0

Badette 4-1-0

Coffin for Negro Child 0-15-0 [17]

The record of Henry Clay’s order for furniture from Porter Clay is interesting not only from the standpoint of patronage, variety, contemporary domestic needs, and the decorative arts, it is also valuable from an economic standpoint. Porter Clay appeared to have learned New York prices as well as New York fashions, and he brought both back to Kentucky with him. In fact, his prices tend to surpass those of his celebrated New York contemporary, Duncan Phyfe. Porter Clay charged his brother Henry £27 for a sideboard. On 26 July 1800, Duncan Phyfe charged Mr. Brewerton of New York £26 for a sideboard—on par with Porter Clay’s price—however, on 28 December 1802, Phyfe charged Mr. Morewood £16 for a sideboard, £11 less than Clay’s. For his brother’s tea table, Porter Clay asked £7-10-0; on 26 July 1800, Duncan Phyfe charged Mr. Brewerton £12 for a pair of tea tables, or £6 each. Porter Clay charges £2-18-0 for a toilet table; for four toilet tables, Phyfe charged only £1-16-0 to Mr. Brewerton. For a pair of card tables, however, both Henry Clay and Mr. Brewerton paid £15.[18] In a newspaper advertisement as late as 1807, Porter Clay sensitively referred to “some reports, which have been ingeniously circulated, about my extravagant charges.”[19] Clearly, Porter Clay was establishing himself as a prestigious artisan seeking a carriage trade clientele.

The variety of furniture forms made in Porter Clay’s shop can be gleaned from the order he fulfilled for his brother Henry: sideboards, chairs, settees, card tables, tea tables, toilet tables, knife boxes, beds, and other objects. Although there are no known signed or labeled specimens of Porter Clay workmanship, he may have simply been following a local practice of not signing or labeling furniture. In her Checklist of Kentucky Cabinetmakers, Edna Talbott Whitley pointed out that the only known labeled example of early Kentucky furniture is a chair by Thomas Tradore Burns of Georgetown, Scott County.[20] Attribution of furniture to Clay’s shop, therefore, has been made on the basis of tradition, provenance, construction elements, and design features. A comprehensive examination of furniture attributed to Porter will be presented in the forthcoming companion to this article: Porter Clay, “A Very Excellent Cabinetmaker”—Part Two: Associated Furniture by Macklin Cox.

The first scholar to study furniture made by Porter Clay was Lexington historian and salon host Colonel James Maurice Roche. As early as March of 1940, he was recorded as being aware of two Porter Clay tables.[21] A newspaper article ten days later, on Roche’s eighty-second birthday, noted that “At present, Mr. Roche is keenly interested in tracing down tables constructed by Porter Clay, a brother of Henry Clay and one-time cabinet maker in Lexington.”[22] One of the tables enumerated by Colonel Roche belonged to his friend, Judge Charles Kerr, editor of the 1922 multi-volume History of Kentucky. That table had descended to Judge Kerr’s wife, Linda Payne Kerr, and offered a provenance tracing back to Kentucky’s Robert Wickliffe (Figure 5), an attorney and one of the most prominent political figures of the commonwealth and a one-time supporter of Henry Clay.[23] The table, in a private collection, is representative of the type Kentucky decorative arts specialists associate with Porter Clay’s shop (Figure 6).[24] A pair of games tables was listed in Henry Clay’s furniture order from his brother, and the tables illustrated in Figure 7 comprise the only extant matched pair attributable to Porter Clay’s shop; that said, as of yet, none of the bespoke work documented in Henry Clay’s ledger has been confidently linked to surviving examples. Most of the furniture appears to have been dispersed in an auction sale at Clay’s Ashland estate in 1825, after his appointment as Secretary of State.[25]

It is not know where Porter Clay located his shop when he returned to Lexington in 1799. Quite likely, however, he was working on Mill Street, at the northeast corner with Church Street, a site that he would later purchase from the estate of Francis McDermid (Figure 8).[26] The location placed Porter Clay’s home and shop in a neighborhood with strong family ties. He would have been on the opposite side of Mill Street from the homes of his brother Henry Clay and Henry’s brother-in-law Thomas Hart as well as next to Henry’s law office (Figure 9). Today, the law office and Porter Clay’s home and shop are separated by First Presbyterian Church. Also, a block further down Mill Street, at the northwest corner of Short Street, was the home of James Brown, Kentucky’s first secretary of state, later a United States Senator from Louisiana, and then American Minister to France during the period when Henry Clay was the United States Secretary of State. Like Clay, Brown, too, had been a student of George Wythe in Virginia. Of particular note is that Brown was married to Ann Hart, the sister of Henry Clay’s wife, Lucretia Hart. This span of Mill Street was a physical manifestation of the connections between the Clay, Hart, and the Brown families.

On Tuesday evening, 8 March 1803, a fire broke out in Porter Clay’s shop.[27] “By the exertions of the citizens, the house was saved without being very materially injured,” noted The Kentucky Gazette of 15 March (Figure 10). “Mr. Clay,” the article continued, “lost about 300 dollars in tools and furniture.” He replaced his tools and restocked his inventory and continued on in his trade. A year later, on 11 April 1804, Porter Clay married (Figure 11). His bride was Sophia Grosh, who was brought to Kentucky with her sisters, Eleanor and Catherine Grosh, from Maryland under the care of Thomas Hart, Henry Clay’s father-in-law and Porter Clay’s neighbor.[28] Sophia would have grown up as an integral member of the Hart household—and Thomas Hart Jr. married her sister, Eleanor Grosh. The third sister, Catherine Grosh, married John Wesley Hunt, considered to be Kentucky’s first millionaire. Through this marriage, Porter Clay further allied himself among the Lexington’s foremost families and the Mill Street community.[29]

When Joseph Charless published Lexington’s first city directory in 1806, he included “Porter Clay, Cabinet Maker,” located on Mill Street. By the time of the directory’s publication, however, Clay’s Mill Street quarters were about to become a dancing school, a development advertised in March of that year as being in the house “lately occupied by Mr. Porter Clay.”[30] Sometime prior to March 1806, Clay had built a new brick residence and shop located near Main Street, behind Lexington’s First Kentucky Bank, designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe for the Kentucky Insurance Company and completed in 1804.[31] Clay ran the following newspaper notice, dated 7 December 1805 (Figure 12):

PORTER CLAY,

Cabinet and Chair Maker,HAS lately removed his Shop to his new brick house, which he has built for the purpose, on Bank Alley immediately back of the Bank… where he has on hand a stock of stuff, equal to any in this State. FURNITURE of the newest and most elegant fashions, may be had on the shortest notice, executed in as neat a manner as any where in the United States. He flatters himself, that from the many sources of information which he has had in his line of business; the regular correspondence which he has kept with all the principal Cabinet Makers both in Philadelphia and New-York, that he will be able to give general satisfaction. [32]

In July of 1804, Porter Clay accepted an apprentice named George Armstrong. Armstrong was to be nineteen years old on 16 September of that year and was to be bound to Porter Clay until the age of twenty-one, in 1806.[33] There is no record showing whether Armstrong remained with Porter Clay afterwards.[34] Very likely, Porter Clay took on a number of additional apprentices, and one of these was Benedict Thomas, who later moved to Nashville, where he published an advertisement in June 1810 for the firm of McLaurine & Thomas, cabinetmakers, with Porter Clay’s endorsement:

Lexington, May 17, 1810. I do certify that Benedict Thomas served his apprenticeship with me, that he behaved himself always as a good and faithful young man should do, he also worked as a journeyman in my shop for sometime after his apprenticeship expired, and when he left my employment he was a master of his business. Given under my hand and date above mentioned. Porter Clay. [35]

By the autumn of 1816, Benedict Thomas had returned to Kentucky, where he took on an apprentice, fifteen-year-old William Spillman, “to learn the trade of a cabinetmaker” in Scott County.[36]

A newspaper notice of 6 October 1807 stated that the work of Porter Clay’s shop “will be carried on hereafter under the firm of CLAY AND WILSON.” His new partner, Robert Wilson, was an Englishman who arrived in Fayette County around 1792 and established himself as a cabinetmaker prior to his partnership with Porter Clay.[37] The 1806 directory showed him on Mulberry Street (later Limestone Street). The appearance of apprentices and the emergence later of a partner further indicate that Clay did not work alone in his shop. At the time that Clay announced his partnership with Robert Wilson, he also stated that he had just returned from a tour of the eastern United States, an indication of his ongoing interest in the work of practitioners in the major cities. Interestingly, too, he announced that the firm was reducing its prices.[38]

By the time that Clay went into partnership with Robert Wilson in the fall of 1807, he may have been considering withdrawing from the field of cabinetmaking. In the 19 January 1808 issue of the Gazette, Clay and Wilson declared that their partnership was dissolved. A few weeks later, in the same newspaper, the partners again placed their announcement of dissolution, but directly above it Clay placed a notice that explicitly stated that the firm was now the business of Robert Wilson, a craftsman “whose qualifications I conceive to be inferior to none in the western country” (Figure 13).[39] Porter Clay sold his Lexington building later in 1808, and in the fall of 1809 Wilson himself left the building on Bank Alley and moved his shop to a location on the south side of Main Street near Postlethwaite’s Tavern. Here, according to the memoirist William Leavy, Wilson “had the largest and best Shop of the kind that had been established in Lexington.”[40]

In the winter of 1808, Porter Clay had also announced to the Lexington community that he had joined William Smith in the “Iron Works of Red river, lately occupied under the firm of Clark and Smith.”[41] On 26 December 1807, Clay had signed a seven-year lease with the executors of the estate of Robert Clark Jr. to rent Clark’s half of the Red River Iron Works. Clark’s partner, William Smith, owned the other half, with rights for use of the forge.[42] Together, Clay and Smith proposed to erect a sawmill for eighteen or more saws. Under terms of the lease, Clay was permitted to cut up to 100,000 board feet of lumber free per year. Newspaper advertisements on 3 and 24 May 1808 revealed that the sawmill had been erected on the Red River. In addition to the sawmill, Smith and Clay represented Harrison Monday in a boat building enterprise at the mouth of Tate’s Creek. An advertisement of this period reads: “THOSE gentlemen engaged in shipping from this country can be furnished with a BOAT in four day’s notice, during the ensuing season by applying to SMITH & CLAY.”[43] The partners afterwards marketed the boats through Clay’s brother-in-law Thomas Hart Jr. in Lexington.[44]

Willard Rouse Jillson published a study of the Red River Iron Works in which he portrayed William Smith as a predatory and difficult individual. Of Smith’s settlement of affairs with the Clark family following the death of his earlier business partner, Jillson wrote that by 1809 Smith had “divested the six Clark children of every piece and class of property included in their original patrimony.”[45] At this point, Porter Clay and Smith had collaborated in real estate, a sawmill, and a boat-building enterprise. Although Jillson makes no mention of Porter Clay’s involvement in the Red River Iron Works, his analysis of Smith’s conduct may explain why, on 30 November 1808, Clay sought from Robert Clark’s executors, William Smith and James Clark, release from his seven-year arrangement and from any further involvement in their business. Documentation for this break was recently discovered among the unrecorded loose papers of the Clark County courthouse by historian Harry Enoch.[46] Regardless of ceasing to do business with Smith, Clay appears to have gone forward with a sawmill of his own, as he contracted with his brother-in-law Thomas Hart Jr. to provide lumber for Hart’s boatyard in January of 1809 and advertised for sawyers the following April.[47]

From an advertisement in the Kentucky Gazette of 2 July 1811 it is known that Porter Clay was living on Main Street in Lexington; a house he occupied there, owned by the silversmith Samuel Ayres, was offered for rent.[48] Although Porter Clay had been active in Lexington from his apprenticeship onward, he also retained an interest in his hometown of Versailles, and from 1810 through 1815 he served as manager of the Versailles Dramatic Club. However, by mid-1811, he had decided on a move from Kentucky to his native Virginia.

Nathaniel P. Watkins, Porter Clay’s half-brother from Versailles, attended the Transylvania University Law School from 1806 to 1808 and, in the footsteps of Henry Clay, was entering into the legal profession at about this time.[49] Seeing a brother and a half-brother focused on careers in the law, Porter Clay re-oriented his own interests toward the legal profession. When he had wished to advance himself in the craft of cabinetmaking, he moved to New York. Now, in pursuit of legal training, he moved to Richmond, Virginia, where Henry Clay had gained his preparation in law. An entry in the Henrico County Order Book, dated 2 November 1812 reads: “Ordered that it be certified that Porter Clay, who wishes to obtain a license to practice law, is a person of probity, honesty and good demeanor, that he is upwards of twenty-one years of age, and hath been a resident of this county for the last twelve months.”[50]

In 1813, the Kentucky Reporter announced that Porter Clay would practice law in Nicholasville, Versailles, and Lexington.[51] On 13 April 1815, he was admitted to the Woodford County Bar. Also during this period he became a justice of the peace in Woodford County. He also served as Woodford County Attorney.[52] Francis Mason, a Versailles barber and later a fellow Baptist minister, spoke of Clay as being “in good practice as a lawyer” in Woodford County. Interestingly, Mason also stated that Porter Clay, along with five others, was stabbed there by an obnoxious attorney. Very likely he refers to the notoriously litigious and homicidal John U. Waring, once described in a murder indictment as “moved and seduced by the instigation of the devil.”[53] One of Waring’s clients was Jereboam Beauchamp, who killed Colonel Solomon P. Sharp in Frankfort in 1825, an event that gained literary fame as “the Kentucky Tragedy.”[54] Porter Clay and Waring carried on a suit against each other in Woodford County Court in May and June of 1817, Clay’s suit being for assault and battery. Waring, who was a defendant in court every term for twenty-five years, was eventually murdered in Versailles in March of 1845.[55]

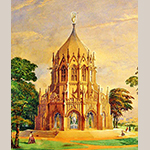

Following Porter Clay’s move to Versailles to practice law, yet another shift of interests emerged in his life. Of his brother, Henry Clay once wrote, “In early life, after he had grown up to manhood, Porter Clay appeared to be a confirmed Deist, but about the year 1814 or 1815, he became seriously religiously inclined.”[56] Their father had been a Baptist minister of great conviction and was even jailed for his militancy before the American Revolution. Their mother was a fervently religious woman, and, perhaps as a result of his move to Versailles, Porter Clay was more frequently subjected to her beliefs. Not long after Porter Clay moved to the south side of Morgan Street in Versailles, his mother and stepfather retired from their tavern to a farm three miles from town on the McCowan Pike. In 1817, at the age of 38 years old, Porter Clay was converted into his mother’s congregation, the Clear Creek Baptist Church, and baptized by the Reverend Ambrose Dudley. Clay became a trustee of the Baptist Church of Versailles and played a role in acquiring a town lot for its sanctuary, the Big Spring Church, in 1819 (Figure 14).[57] He recalled that at the time of his conversion, “I was then practicing law at Versailles, Kentucky. I soon discovered that that course of life was inconsistent with the pledge I had made to God… . I determined to throw myself under the protection of my Heavenly Father and wait His good providence rather than make my thousands in an unholy Calling.”[58]

However, in May of 1820, Kentucky Governor Gabriel Slaughter, perhaps influenced by Henry Clay, appointed Porter Clay to be the state’s Auditor of Public Accounts at $3,000 per year (Figure 15).[59] Newly-elected Governor Adair reappointed him later that year, and he was afterwards successfully re-elected to the post. Moving to Frankfort, he reconciled both church and state as a prominent Baptist and a public official.[60] In an autobiographical letter of 1848 he recalled:

I found a small church there [at Frankfort] with, I think, 16 members, poor and persecuted by other denominations. They called me to the care of them, and I can say that we lived in great harmony for several years, and they grew in numbers and grace. In the conscientious discharge of my duty as auditor I incurred the displeasure of a very wealthy and influential member of the church who was a member of the legislature at the time. He determined to effect my ruin, either as auditor of public accounts or as pastor, or both. The legislature saw through the whole and sustained me in the act complained of, and the people did the same at the next election, but he was more successful with the church. They suspended me from my ministerial labors by giving heed to his falsehoods and plausible accusations, concocted in malice, and having no foundation in truth. [61]

As Clay became a leader in the Frankfort Baptist Church, he served from time to time as the church’s clerk and occasionally as its moderator. By November of 1822, still a layman, he was asked to preach one Sunday each month. He was entrusted with the key to the church, which was kept in the state auditor’s office. In 1823, the Franklin County Court granted Porter Clay testimonials of honesty and probity and empowered him to perform marriages.[62] Moreover, he was formally ordained. John Taylor, in his 1827 History of Ten Baptist Churches, declared the ordination of Porter Clay “a farce of the most outlandish kind, that I ever knew,” recalling one among the many arcane questions from Clay’s examination: “Do you recollect brother, that you ever knew a sheep turned into a goat or a goat into a sheep?” to which Porter Clay replied correctly, “I do not recollect that I ever knew such a circumstance.”[63] By the fourth Saturday in February 1824, “by prayer and imposition of hands,” he was made minister of the New Testament at the Frankfort Baptist Church.

Porter Clay’s rapid emergence as a minister was soon imperiled by his abrasive relationship with the “very wealthy and influential member of the church” mentioned in the 1848 autobiographical letter. His adversary was merchant, bank director, and state senator Jephthah Dudley, a member of the church from its founding on 26 February 1816.[64] In early 1824, Dudley placed in the church minutes a notice that he (Dudley) had infringed on the church rules “in the act of a personal encounter with an individual in this place”—very likely Porter Clay—“since our last meeting,” an act for which he was excused. Jephthah Dudley was married to Sarah Lewis Clay, the widow of General Green Clay of Madison County, who, it is thought, commissioned furniture from Porter Clay when he was a cabinetmaker.[65] Ironically, Senator Jephthah Dudley, himself an occasional clerk of the church, was also the son of the Reverend Ambrose Dudley who had baptized Porter Clay in Woodford County in 1817. In addition, Reverend Dudley died on 27 January 1825 in Porter Clay’s old shop on Mill Street in Lexington, by then the home of his son Dr. Benjamin W. Dudley of the Transylvania Medical School.[66]

Church historian Charles Hinds suggested that Jephthah Dudley, appealing to the concept of the separation of church and state, felt that Porter Clay should not be both a Baptist minister and the state’s chief financial officer. However, contradictory opinions about the future direction of the church were more likely the source of discord. At this period there was a growing division among Kentucky Baptists between Missionary Baptists and Antimission Baptists. Porter Clay, according to Hinds, was a Missionary Baptist. Jephthah Dudley, by contrast, was militantly antimissionary. Dudley’s brother, Reverend Thomas Parker Dudley, actually split the church, leading the Antimission Baptists into a separate organization with the Particular Baptists.[67]

At some point, Clay accused Dudley of untruthfulness and corruption. He later recanted, while at the same time raising his New Testament in the air and still insisting that Dudley was at fault from an unidentified passage in Chapter VIII of the book of Matthew. An apparent lack of interpersonal suavity hints that Clay’s theological reasoning was less polished than his sideboards and tea tables. In the manuscript minutes of the church in the Kentucky Historical Society, Senator Dudley, with some lack of piety, reportedly shook his fist at Reverend Porter Clay and declared, “I’ll split you to the ground if you call in question my honor and veracity.”[68] Tensions between the two were translated into charges and counter charges that led to a sensational church trial. Reverend Porter Clay laid out three charges against Senator Dudley; Senator Dudley laid out thirty-one charges against the minister, with an additional charge of insanity. One summary of the event recorded that “The controversy between Porter Clay and [Jephthah] Dudley shook the church to its foundation.”[69] As a result of the conflicts of this curious episode, on 25 November 1826, both men were temporarily suspended from church membership. A trial went forward, and on 5 October 1827, quoting the minutes, “The resolution which was offered at a former meeting, having for its object the putting away from us Brother Porter Clay, was taken up and adopted.”[70] As if by the bell, book, and candle of the ancient church, Reverend Porter Clay was excommunicated by his own congregation (Figure 16). Throughout the ordeal, Clay appeared at best stubborn, inconsistent, and quibbling. His unwillingness to engage in a solution ended his affiliation with the church and the pulpit in Kentucky. Unlike his famous brother, Porter Clay was not a Great Compromiser.

The late summer and fall of 1829 saw a downward spiral in Porter Clay’s family circumstances. Between August and December, death came to his daughter Eleanor, his wife Sophia, his brother John, his stepfather Henry Watkins, and his mother Elizabeth Hudson Clay Watkins. In a little over three months, he lost five of his closest family members.[71] A widower at the end of September 1829, Porter Clay remarried six months later, on 5 April 1830.[72] This second marriage only accelerated the downward thrust of his career. His new wife, younger by five years, was Elizabeth Logan Hardin (Figure 17), described as “the elegant widow” of United States Senator Martin D. Hardin of Frankfort.[73] The Hardins, a socially prominent couple, had both been painted by Kentucky’s leading portrait artist, Matthew Harris Jouett, who had also painted Porter Clay’s famed brother, Henry Clay.[74]

At the time of his death, Senator Hardin owned a farm, called Locust Hill, today called Scotland, outside of Frankfort, astride the Franklin and Woodford county lines. Porter and the senator’s widow, wrote Henry Clay, “occupied one of the best farms in Kentucky.”[75] However, Senator Hardin had accumulated over $50,000 in debt.[76] Porter Clay complained of the hardships in managing Locust Hill: “It takes more than the money I received from the hemp to pay our present overseer whose time expires the first of September… . If I stay here seven years I will never have another overseer.”[77] Although now stepfather to Hardin’s son, John J. Hardin, Porter Clay deferred to him and to Hardin’s mother—Senator Martin Hardin’s direct heirs—in the management of their financial affairs.[78]

An early defining issue upon Porter Clay’s union with the Hardins was the sale of Locust Hill. Porter Clay wrote to John J. Hardin on 10 November 1833 that Locust Hill had been sold to Robert W. Scott of Frankfort.[79] Porter Clay then resigned as state auditor in January 1834.[80] Historian Thomas D. Clark described the farm at the time of the sale as “poorly managed and run-down.”[81] Henry Clay summarized the financial straits in which his brother and sister-in-law found themselves: “Their removal was, perhaps, unfortunate,” he wrote, “as by misfortune, it led to the loss of all his property and some of hers.”[82]

Porter Clay’s correspondence during this period, a time that included the cholera plague of 1833, indicated that he, along with his new wife and her family, were making plans to acquire land in Illinois in order to join her son. John J. Hardin, who had trained in law at Lexington’s Transylvania University, had moved to Illinois in 1830 and served in the Black Hawk War and in the Illinois Mormon War, rising to the rank of major general. [83] With what resources remained after settling her late husband’s debts and the sale of Locust Hill, Elizabeth Hardin Clay acquired six acres in Jacksonville, Morgan County, Illinois; she then built a house there, now known as the Porter Clay House (Figures 18 and 19).[84] According to surviving documents, the Clays acquired house plans from the noted Kentucky architect Gideon Shryock, who had recently finished building Kentucky’s third capitol in downtown Frankfort. The second capitol, along with Porter Clay’s office, had burned in 1824. Lumber, doors, doorframes, sash, glass, paint, tin, locks, and other necessities for construction of the house were to be shipped from Kentucky to Illinois.[85] Porter and Elizabeth Hardin Clay left Locust Hill for Illinois on Tuesday, 25 February 1834.[86]

The Clays, along with John J. Hardin, occupied the new dwelling in Jacksonville. Porter Clay’s stepson was the founder of the Illinoisian newspaper in Jacksonville in 1837, served in the Illinois House of Representatives from 1836 to 1842, and was elected to Congress as the Whig candidate for the term of 1843 to 1845.[87] Hardin was aggressive by temperament and was said to have challenged Jefferson Davis to a duel, a confrontation that was rumored to have been averted by Zachary Taylor.[88] An anonymous writer in Ford’s Christian Repository wrote of meeting Porter Clay in 1842 and spoke of the difficult relationship between Clay and his stepson John Hardin: the stepson, in the writer’s words, treated Clay “with marked disrespect.” Another writer stated that Hardin never accepted Clay, “either as his stepfather or as the rightful husband of his mother.”[89]

About 1839, Clay became an outcast from his own home, forced by family tensions to leave his second wife and stepson. He went for a period to Jackson, Missouri to stay with his half-brother Nathaniel Watkins, later a speaker of the Missouri House of Representatives and Confederate general. In response to Porter Clay’s needs, his brother Henry Clay arranged for him to be a representative of the American Colonization Society, an organization that urged slaveholders to free their slaves and to underwrite their transportation back to Africa, to the colony of Liberia. Although Henry Clay was himself a slave owner, he served as president of the Colonization Society. Jared Irwin of Springfield, Missouri wrote in his diary on 8 April 1839:

This evening heard with pleasure Porter Clay, Esq. (Bro. of the Hon. H. Clay) deliver his first lecture in behalf of the “Colonization Society”; he was recently appointed agent of the “great valley” and has this evening commenced upon the duties of his mission, intending to lecture and form Societies through the length & breadth of the Valley. He is quite eloquent. —May success attend him. [90]

The minutes of the society recorded that Clay “traveled over Illinois, Indiana, and Kentucky, organizing many Societies and taking large subscriptions, payable yearly, for ten years, besides remittances in cash.”[91]

During this late phase of Porter Clay’s life, his brother Henry continued to be one of the country’s most prominent public figures. In the election year of 1844, Henry Clay sought the presidency as the Whig party’s nominee but was defeated by Democratic candidate James K. Polk of Tennessee. Polk, like Clay, was a former Speaker of the House of Representatives. Porter Clay’s association with his older brother was well known and involved him in political discussions. An acquaintance from his days in Versailles recalled:

He often came into the shop where I worked, and the conversation sometimes turned on his brother becoming President, a question then considerably agitated in Kentucky. He was very confident that Henry would never reach the presidential chair, fortifying his opinions by various well considered statements of the condition and strength of parties in different sections of the United States. [92]

Not all such exchanges, however, were friendly. In mid-December 1844, The Baltimore Sun referred to an article in the Jacksonville, Illinois Morgan Journal that gave “an account of an outrage committed upon the Rev. Porter Clay, by some rascals, simply because he is the brother of Henry Clay.”[93] Details of the outrage against the sixty-five-year-old minister were not recorded.

In February of 1847, Porter Clay’s stepson and nemesis John J. Hardin, already a military veteran, was commissioned a colonel in the Illinois Volunteer Infantry to serve in the Mexican War. On 23 February 1847, Colonel Hardin died leading a charge in the Battle of Buena Vista. In the same war, in the same battle, on the same day, Porter Clay’s nephew, Henry Clay Jr., a West Point graduate and a Lieutenant Colonel in the 2nd Kentucky Volunteers, was also killed leading yet another charge.[94] Both battlefield events were commemorated in lithographs published by Nathaniel Currier.[95]

Porter Clay was by then a wandering Baptist preacher. Church historian Ermina Jett Darnell wrote that Clay was “an evangelist to the border settlements of Illinois and Missouri, preaching to white, black, and red men. He is said to have been the first to preach in the English language west of the Mississippi.”[96] In Illinois, he is known to have been pastor of churches both at Carrollton and Quincy.[97] The year 1848 is illustrative of Porter Clay’s itinerant status: A history of the Clay family indicated that he began the year preaching in Alton, Illinois; he then moved to Shelbyville, Kentucky; and in the fall of the same year moved to Helena, Arkansas, the place where his brother John had been buried following his death on a Mississippi River steamboat in 1829. Porter became a pastor of the New Hope Baptist Church in Helena. At New Hope Baptist Church, according to an 1855 Arkansas Baptist History, he “labored as pastor for six months, preaching two Sabbaths at this place, and the remainder elsewhere. In the spring of 1849, he went into the southern part of the state.”[98]

An acquaintance recorded Porter Clay’s last months: “At length he reached Camden, Arkansas. He held meetings every night for a considerable time. A church was organized, and he seemed likely to spend his last years there in active ministry.”[99] However, in February of the new year, at the age of 71, he was stricken by a fever and confined to his room at the Southerland House Hotel. After suffering for several days, Porter Clay died on Saturday, 16 February 1850.[100] His brother Henry Clay (Figure 20) also died in a hotel room, two years later in Washington, DC.

A national competition was held for the design of Henry Clay’s tomb. The winning submission was an ornate thirteen-sided Gothic Revival pavilion topped by an angel sounding the trumpet of fame (Figure 21).[101] The design was so fantastic that it could never be built. By contrast, there was no national competition for a monument to Porter Clay. In fact, there was no monument at all. Porter Clay was buried in the Oakland Cemetery in Camden in an unmarked grave. After a period of neglect, his grave was marked with a wooden headboard. The New Century Club of Camden erected a stone monument of eight by eighteen inches at Porter Clay’s burial site in 1910, and by 1913 Clay’s name “was almost obliterated by the weather.”[102] This marker was replaced in 1939 with a larger marble monument placed by the Liberty Baptist Association of South Arkansas.

The Lexington Observer & Reporter carried a brief obituary notice for Porter Clay in its issue of 13 March 1850.[103] Also in the year of his death, Stryker’s American Register and Magazine carried the following tribute, making no mention of his work in cabinetmaking, the law, agriculture, as an emancipationist, or to his tenure as a political functionary:

He was the last living full brother of the Hon. Henry Clay. Like him he was, in all the attainments of education, self-made. Although his career was less known, he was distinguished and endeared to the circle of his acquaintances by his quiet and unobtrusive virtues, by his perfect uprightness of conduct, and by his fervent devotion, in and out of the pulpit, to the Christian religion.[104]

The fullest and most sympathetic treatment to appear, however, was a brief essay by Senator Henry Clay in The Baptist Memorial and Monthly Record.[105] Writing anonymously, the Kentucky statesman wrote of his brother: “After he had been divested of all his property upon earth, and had not a cent remaining, his brother Henry offered him a residence and the means of support at Ashland [Figure 22]; but he declined it, stating that he owed his service to God and that his Maker, he had perfect confidence, would take care of him.”[106] Clay wrote in a letter to his wife, Lucretia, that Porter “has gone, poor fellow… . He had but little to attach him to this life.” [107]

But Porter Clay led an eventful life. He seemed strangely representative of the mad artist, a man who pivoted from the material to the spiritual world, rejecting prosperity and embracing poverty. Half-orphaned, a runaway from his master, and burned out of his cabinet shop; sued, stabbed, farcically ordained, tried, suspended, accused of insanity, and excommunicated; widowed, outraged by rascals, evicted, bankrupted, homeless, and preceded in death by all of his children; Porter Clay, “a most excellent cabinetmaker”—indeed, perhaps the most sophisticated of the early cabinetmakers of Kentucky—was at last propelled into oblivion and an unmarked grave. Eclipsed in achievements by his older brother Henry Clay and by his younger half-brother Nathaniel Watkins, Porter Clay seems by contrast to have possessed a self-destructive demon that confounded his every effort in life. Had his story been fictional instead of real, Porter Clay would be studied today as the prototypical literary anti-hero.

James D. Birchfield is the emeritus Curator of Rare Books for the University of Kentucky Library’s Special Collections Research Center. He has a long list of exhibits, publications, and lectures documenting and highlighting the history and culture of the Commonwealth of Kentucky. He can be contacted at [email protected].

APPENDIX: PORTER CLAY TIMELINE

|

1779: |

Born in Hanover County, Virginia to Reverend John Clay and Elizabeth Hudson Clay |

|

1781: |

Reverend John Clay died |

|

1791: |

Moved with mother and step-father, Henry Watkins, to Versailles, Kentucky |

|

1792: |

Probably began apprenticeship with cabinetmaker Thomas Whitney in Lexington, Kentucky |

|

1798: |

Ran-away from Thomas Whitney’s shop |

|

1798/99: |

Worked as a journeyman cabinetmaker in New York City |

|

1799: |

Returned to Lexington from New York |

|

1803/04: |

Commissioned to make furniture for Henry Clay’s new house |

|

1803: |

Fire damaged his cabinetmaking shop on Mill Street, Lexington |

|

1804: |

Married Sophia Grosh in Lexington |

|

1806: |

Built a new house and cabinetmaking shop on Bank Alley, Lexington |

|

1807: |

Partnered with Robert Wilson to create the firm Clay & Wilson |

|

1808: |

Dissolved the partnership of Clay & Wilson |

|

1808/09: |

Began and ended two business ventures with William Smith: the Red River Iron Works and a boat-building business |

|

1811: |

Moved to Richmond, Virginia to begin law education |

|

1813: |

Announced that he would practice law in Nicholasville, Versailles, and Lexington |

|

1815: |

Admitted into Kentucky’s Woodford County Bar Association |

|

1817: |

Baptized at the Clear Creek Baptist Church in Versailles |

|

1820: |

Appointed to be Kentucky’s Auditor of Public Accounts and moved to Frankfort |

|

1824: |

Ordained a minister at the Frankfort Baptist Church |

|

1827: |

Excommunicated by the Frankfort Baptist Church |

|

1829: |

Death of his wife, daughter, mother, step-father, and brother |

|

1830: |

Married Elizabeth Logan Hardin in Frankfort |

|

1833: |

Sold Locust Hill |

|

1834: |

Resigned as Kentucky’s Auditor of Public Accounts |

|

1834: |

Moved to Jacksonville, Illinois and built a house designed by Gideon Shryock |

|

1839: |

Left his wife and stepson in Jacksonville to live in Jackson, Missouri with his half-brother Nathaniel Watkins |

|

1840-1850: |

Worked as an itinerant preacher in Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, and Arkansas |

|

1850: |

Died at the age of 71 in Camden, Arkansas |

[1] The author acknowledges the following, whose advice and/or previous research has forwarded the development of this article: Daniel Kurt Ackermann (MESDA), Gary Albert (MESDA), Mary Frances Alkire (Jacksonville, Illinois Area Genealogical & Historical Society), Hubert Boddie (Ouachita County Historical Society), Macklin and Sharon Cox, Jennifer Duplaga (Kentucky Historical Society), Harry G. Enochs, Gary D. Gardner, B. J. Gooch (Transylvania University), Scott Erbes (Speed Art Museum, Louisville), James Holmberg (Filson Historical Society, Louisville), Wayne Johnson (Lexington, Kentucky Public Library), William J. Marshall, Jr. (Director, Special Collections, University of Kentucky Libraries), Marti Martin (Woodford County, Kentucky Historical Society), Greg Olson (Jacksonville, Illinois Public Library), Kim Wilson-May (MESDA), Marianne P. Ramsey (Clifton Anderson Antiques), Bill Roughen Photography + Design, Deirdre Scaggs (Associate Dean, Special Collections Research Center, University of Kentucky), Denise Shanks (Lexington, Kentucky Public Library), Henry Clay Simpson, and Pamela Withrow (Jacksonville, Illinois Public Library).

[2] Charles Kerr, History of Kentucky (Chicago, IL: American Historical Society, 1922), 3: 4; Elizabeth Patterson Thomas, Old Kentucky Homes and Gardens (Louisville, KY: Standard Printing Company, 1939), 54.

[3] The Papers of Henry Clay (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1991), 10: 16.

[4] For genealogical and biographical information, see John Frederick Dorman, “Clay,” in Adventurers of Purse and Person: Virginia 1607-1624/5 (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2004), 1: 682; Henry Clay (anonymous), “Biographical Sketch of Rev. Porter Clay,” The Baptist Memorial, and Monthly Record, Devoted to the History, Biography, Literature and Statistics of the Denomination, Enoch Hutchinson, ed., vol. X, New Series vol. III (1851), 213-214, reprinted in Starlight: Or Concise Biographies and Portraits of Eminent Deceased Ministers of the Gospel (New York: Edward H. Fletcher, 1855) (online: http://archive.org/details/baptistmemorial05unkngoog [accessed 10 December 2014]); William Cathcart, “Porter Clay,” Baptist Encyclopedia (Philadelphia, PA: L. H. Evert, 1883), 3: 232; Charles Kerr, ed., History of Kentucky (Chicago, IL: American Historical Society, 1922), 3: 4; Zachary F. Smith and Mary Rogers Clay, The Clay Family (Louisville, KY: The Filson Club, 1899), 9-10, 12, 18 20, 21, 90; Newton Bateman and Paul Selby, eds., Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois, vol. I (Chicago, IL: Munsell Publishing, 1912), 106; “Humble Brother of Henry Clay: Man Who Cast Away Ambition Became Obscure Clergyman and Lies in Almost Forgotten Arkansas Grave,” Lexington Leader (Lexington, KY), 13 March 1913; William E. Railey, History of Woodford County (Frankfort, KY: Roberts Printing, 1928), 273-274; Edgar Erskine Hume, “Auditor of Public Accounts: Porter Clay,” Lafayette in Kentucky (Frankfort, KY: Transylvania College and the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Virginia, 1937), 9; Dan M. Bowmar, “Porter Clay, Henry Clay’s Brother: Spent Early Life Here, Was County Attorney—Converted in Local Revival, Became Noted Preacher,” Woodford Sun (Versailles, KY), 4 March 1940; “Henry Clay’s Mother Ran Famous Tavern on Site Occupied by Amsden Bank Building,” Woodford Sun (Versailles, KY), 7 July 1960; Edna Talbott Whitley, A Checklist of Kentucky Cabinetmakers From 1775-1859 (1969; 2nd ed., Paris, KY: Edna T. Whitley, 1982), 18 and “Supplement,” 1; Ethel Hall Bjerkoe, The Cabinetmakers of America (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1957), 65; and Thomas D. Clark, Frontier America: The Story of the Westward Movement (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1959), 213.

[5] “Henry Clay’s Father and Brother Preachers,” The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, GA), 16 October 1904, reprinted as “Henry Clay’s Father,” Iowa City Press-Citizen (Iowa City, IA), 19 November 1904: “Robert B. Semple, in his History of Virginia Baptists, says that the Black Creek Baptist Church in Hanover County was originated by John Clay and that he was pastor of the Chickahominy Church and did much missionary work in the region around.”

[6] Robert Remini, Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union (New York: W.W. Norton, 1991), 3. Zachary F. Smith and Mary Rogers Clay, The Clay Family (Louisville, KY: The Filson Club, 1899), 90.

[7] Guardian Accounts, Woodford County Will Book A, October Court 1795 and Will Book B, December Court 1797, see Dona Adams Wilson, ed., Woodford County, KY Will Book Abstracts (Lexington, KY: Lynn Imaging, 2003), 1-2.

[8] Remini, Henry Clay, 12, xvii.

[9] Bowmar, “Porter Clay, Henry Clay’s Brother…”.

[10] Thomas Whitney (1764-1819) was buried in the Old Episcopal Burying Ground, Lexington, see Frances Keller Swinford Barr, Old Episcopal Burying Ground (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 2002), 55; J. Winston Coleman Jr., Lexington’s First City Directory (1806; reprinted, Lexington, KY: Winburn Press, 1953), 6 (Main Street); J. Winston Coleman, Lexington’s Second City Directory (1818; reprinted, Lexington, KY: Winburn Press, 1953), 18 (Main Street); William A. Leavy, “Memoir of Lexington and Its Vicinity: With Some Notice of Many Prominent Citizens and Its Institutions of Education and Religion,” Register of Kentucky State Historical Society, vol. 41, no. 137 (October 1943), 329: “N.E. corner of Limestone & Main 2 houses Residence and Shop of Thomas Whitney, one of the earliest Cabinet Makers”; Will of Thomas Whitney, signed 3 August 1819, recorded Will Book E, 107, probated November Court 1819; Michael L. Cook and Bettie A. Cummings Cook, eds., Fayette County Kentucky Records (Evansville, IN: Cook Publications, 1986), 5: 235.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Henry Clay (anonymous), “Biographical Sketch of Rev. Porter Clay,” 213.

[13] John L. Scherer, New York Furniture: The Federal Period 1788-1825 (Albany: New York State Museum, 1988), 6.

[14] Daniel Longworth, ed., American Almanack, New York Register and City Directory for the Thirteenth Year of American Independence (New York: The Compiler, 1805-1806), iii.

[15] Remini, 17; Thomas Hart with John Clay, Samuel M. Wilson Papers, MSS 52W111, Oversize Ledger Sheet, flat file, Special Collections, University of Kentucky Libraries.

[16] C. Frank Dunn, “Col. Thomas Hart House, ‘Poplar Row,’ ” Old Houses of Lexington, typescript, Lexington Public Library.

[17] Henry Clay Account Book, 70M39, Samuel M. Wilson Collection, Special Collections Research Center, University of Kentucky Libraries.

[18] See Peter M. Kenny et al., “Invoices and Accounts from Duncan Phyfe Relating to Furniture in this Volume,” in Duncan Phyfe: Master Cabinetmaker in New York (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011), 273-279.

[19] “Furniture,” The Kentucky Gazette and General Advertiser (Lexington, KY), 29 December 1807.

[20] Whitley, Checklist of Kentucky Cabinetmakers, 12. Although labels were not in use, a number of Kentucky pieces include signatures incised or written in ink or chalk. For examples, see the cover illustration for Kentucky Furniture (Louisville, KY: Speed Art Museum, 1974) showing Elisha Warner, Peter Tuttle, Isaac Evans; Jessie Poesch, The Art of the Old South (New York: Harrison House, 1989), 197 (Elisha Warner); Marianne P. Ramsey and Diane C. Wachs, The Tuttle Muddle: An Investigation of a Kentucky Case-on-Frame Furniture Group (Lexington, KY: Headley-Whitney Museum, 2000), 30 (Peter Tuttle); and Genevieve Baird Lacer and Libby Turner Howard, Collecting Kentucky 1790-1860 (s.l.: Cherry Valley Publications, 2013), 29 (Peter Tuttle), 79 (Jesse Head), 207 (Thomas McMurray), and 211 (probably Rufus King Summers).

[21] Dan M. Bowmar, “First One Thing, Then Another,” Woodford Sun (Versailles, KY), 21 March 1940.

[22] “James M. Roche 82 Years Old: Historian Observes Birthday Informally,” Lexington Herald-Leader (Lexington, KY), 31 March 1940: “One of these tables is owned by Judge Charles Kerr at Washington; a second is in Kirkwood, Mo., and a third is believed to be in the J. R. Morton residence of Mrs. Anderson Gratz on North Market [actually Mill] street.”

[23] The provenance of the table to 1940, documented by Gary D. Gardner, is 1) Robert Wickliffe and Margaret Preston Howard Wickliffe to 2) Sarah Howard Wickliffe and Judge Aaron Kitchell Woolley to 3) Ellen Douglas Woolley and John Breckinridge Payne to 4) Linda Payne Kerr and Judge Charles Kerr (MESDA Object Database, S-3131). Dan Bowmar wrote in his March 1940 Woodford Sun column “The veteran Lexington historian, J. M. Roche, mailed a copy of The Sun with my story [about Porter Clay] to Judge Charles Kerr, of Washington, D.C. and Lexington, a high authority… Judge Kerr owns a mahogany [no doubt cherry] side table that was made by Porter Clay at a cabinet shop in Lexington, he says, for the Hon. Robert Wickliffe, a distinguished Lexington lawyer. This table came into the Kerr home through Mrs. Kerr, a descendant of Mr. Wickliffe. Mr. Roche has discovered another piece of furniture that was made by Porter Clay, said to be a very unusual table, that is in the possession of Mrs. E. F. Berkeley Jones of Kirkwood, Mo.” The story of Porter Clay’s table for Robert Wickliffe is told again by C. Frank Dunn, “Porter Clay’s Cabinet Shop House (Burrowes’ Mustard Factory), Old Houses of Lexington, typescript, Lexington Public Library.

At the time of his marriage on 1 May 1804 (approximately a month after Porter Clay’s own marriage) to Margaretta Howard of Howard’s Grove, Robert Wickliffe was a resident of Bardstown, Nelson County, Kentucky. He first appeared in Fayette County on the 1807 tax roll (microfilm, Kentucky Historical Society). Porter Clay remained active as a cabinetmaker through 1807; however, since Wickliffe’s wife was from Fayette County, it is likely that they were often in Lexington to visit members of the Howard family. Robert Wickliffe’s table might have been constructed at any time from 1804 (or earlier, if prior to his marriage) through 1807, when Porter Clay sold his interest to Robert Wilson.

[24] The table is featured in “Digging Deep” in Lacer and Howard, Collecting Kentucky, 56.

[25] Sale lots of the auction of 24-25 June 1825 enumerated in The Papers of Henry Clay, 4: 457-462.

[26] Fayette County, Kentucky Circuit Court Book B, 127; see also Book B, 409 (a second recording of the transaction). On 24 May 1804, Porter Clay and William Smith purchased a large parcel of downtown real estate that included Lot 48, the corner of Mill and Church Streets where Clay’s cabinet shop was located. Clay later acquired Smith’s interest in the lot. See Fayette County, Kentucky Deed Book C, 350, where this property is transferred to Thomas Dye Owings on 18 March 1808 and also states that Smith had previously sold his interest to Clay, an otherwise unrecorded transfer.

[27] The building was still owned by Francis McDermid at the time of the 1803 fire. Porter Clay would not purchase the property until 1804.

[28] Kentucky Gazette (Lexington, KY), 17 April 1804; Cook and Cook, Fayette County Kentucky Records, 3: 10.

[29] Possibly influenced by his civic-minded relatives, on 7 May 1806 Porter Clay took the oath of office for a justice of the peace. Public life did not seem to be his calling, and Clay later resigned the position, on 13 February 1809. Ibid, 4: 265.

[30] Kentucky Gazette, 12 March 1806.

[31] The First Kentucky Bank was demolished before the Civil War. James C. Klotter and Daniel Bruce Rowland, eds., Bluegrass Renaissance: The History and Culture of Central Kentucky, 1792-1852 (Lexington: University of Kentucky, 2012), 292-293.

[32] Kentucky Gazette, 12 December 1805. See also Joe Jordan, “Lexington Landmarks: Porter Clay’s Cabinet Shop Still Stands,” Lexington Leader, 1 November 1947. By the mid-twentieth century, Porter Clay’s shop on Bank Alley had become 117 Wrenn Court.

[33] 9 July 1804, Cook and Cook, Fayette County Kentucky Records, 4: 61.

[34] Whitley, A Checklist of Kentucky Cabinetmakers, 18; an error was made by Whitley in suggesting that the Fayette County order books recorded other Porter Clay apprenticeships in 1803 and 1804—not all apprentice agreements were a matter of legal record in the order books, and it is likely that Porter Clay accepted a number of apprentices. The 1805 Fayette County, Kentucky tax roll for 1805 lists Porter Clay’s household as having one male over twenty-one years old (Porter Clay) and two white males over sixteen years old (probably cabinetmaking apprentices) as well as three slaves.

[35] Democratic Clarion and Tennessee Gazette (Nashville, TN), 1 June 1810.

[36] Court session of 4 November 1816, recorded in Court Order Book B, 331, Scott County, Kentucky.

[37] See Mary Clay McClinton, “Robert Wilson, Kentucky Cabinetmaker,” The Magazine ANTIQUES, vol. 103, no. 5 (May 1973), 945-949.

[38] Kentucky Gazette and General Advertiser, 6 October 1807.

[39] Kentucky Gazette, 16 February 1808.

[40] Porter Clay to David Dodge, 5 November 1808, Fayette County, Kentucky Deed Book C, 394. “Removal,” Kentucky Gazette, 15 August 1809; William A. Leavy, “Memoir of Lexington and Its Vicinity,” Register of Kentucky State Historical Society, vol. 41, no. 137 (October 1943), 329.

[41] Kentucky Gazette, 16 February 1808.

[42] Before Clay left the cabinetmaking trade he had partnered with William Smith on several real estate transactions, including the 1804 purchase of downtown real estate that included Clay’s Mill Street shop and home. “Shortly after 1800,” writes Lexington architectural historian C. Frank Dunn, “the youthful Porter, together with William Smith, launched into real estate.” They acquired a large swath of downtown land extending two blocks from Limestone Street to Broadway. According to Dunn, Porter Clay “laid off and gave the Town of Lexington both Market Street and Church Street.” See Dunn, “Porter Clay’s Cabinet Shop House (Burrowes’ Mustard Factory)”; Cook and Cook, Fayette County Kentucky Records, 1: 364, 369, 394, 432, 528; and “Sale to Thomas Dye Owings,” 18 March 1808, Fayette County, Kentucky Deed Book C, 350.

[43] Kentucky Gazette, 11 October 1808.

[44] Kentucky Gazette, 24 January 1809; although the advertisement reads “Thomas Hart,” the reference is to Thomas Hart Jr., as Thomas Hart Sr. had died on 23 June 1808; Thomas Hart Jr. died on 25 November 1809; see Kentucky Gazette of 11 October 1808 and 24 January 1809.

[45] Willard Rouse Jillson, The Red River Iron Works; A Narrative Account of the Rise and Decline of a Basic Industry in Eastern Central Kentucky (Frankfort, KY: Roberts Printing Company, 1964), 21.

[46] Harry G. Enoch, “Porter Clay and the Red River Iron Works,” typescript of research based in part on unrecorded loose papers in the Clark County, Winchester, Kentucky courthouse and other sources, generously provided by the author.

[47] Kentucky Gazette, 24 January 1809; Kentucky Gazette, 4 April 1809.

[48] “Samuel Ayres has a house for rent next door to Joseph H. Daviess and presently occupied by Porter Clay.”

[49] William A. Leavy, “Memoir of Lexington and Its Vicinity: With Some Notice of Many Prominent Citizens and Its Institutions of Education and Religion,” Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society, vol. 41, no. 132 (January 1943), 55.

[50] Henrico County, Virginia Order Book No. 17, 1812-1814, 144 (photocopy, MESDA Object Database, S-7781).

[51] Kentucky Reporter (Lexington, KY), 20 March 1813.

[52] Bowmar, “Porter Clay, Henry Clay’s Brother…”

[53] Lewis Franklin Johnson, Famous Kentucky Tragedies and Trials (Louisville, KY: Baldwin Law Book Company, 1916), 59.

[54] The story of Jereboam Beauchamp is the basis for Robert Penn Warren’s World Enough and Time (New York: Random House, 1950) as well as earlier literary efforts by Edgar Allen Poe, Thomas Holley Chivers, William Gilmore Simms, Charles Fenno Hoffman, and others.

[55] Bowmar, “Porter Clay, Henry Clay’s Brother…”; Francis Mason, The Story of a Working Man’s Life (New York: Oakley, Mason & Co, 1870), 128, 164; Johnson, Famous Kentucky Tragedies and Trials, 59, 66; J. Winston Coleman, Jr., “Francis Waring vs. Jacob Holeman,” Famous Kentucky Duels (Lexington, KY: Henry Clay Press, 1969), 62-63.

[56] Anonymous (Henry Clay), “Biographical Sketch of Rev. Porter Clay,” 214.

[57] Indenture, Porter Clay et al., “Trustees of the Baptist Church in the Town of Versailles, sum of $300, a tract of land in the Town of Versailles, beginning at a stake on Morgan Street, Lot No. 17 [this is where Woodford County Historical Society is located],” Wilson, Woodford County, KY, Deed Book Abstracts, Deed Book H: 1819-1821, 14-15.

[58] Porter Clay’s autobiographical statement is cited, unsourced, by Bowmar, “Porter Clay, Henry Clay’s Brother… .”

[59] He was appointed upon the death of John Madison, Kentucky Reporter, 24 May 1820; re-appointed, Kentucky Reporter, 4 December 1820.

[60] While he was living in Frankfort, both of Porter Clay’s daughters married. Elizabeth married 2 October 1821 to Edmund Haynes Taylor, cashier of the Branch Bank of Kentucky in Frankfort. Eleanor Hart married 4 July 1825 in Clark County to Nathaniel Pendleton Taylor; he became United States Registrar of Lands in Missouri.

[61] Porter Clay to unknown correspondent, 1848, quoted in Bowmar, “Porter Clay, Henry Clay’s Brother… .” In another Woodford Sun article, 28 March 1940, Bowmar quotes from Porter Clay’s response to a publisher who asked for a sketch of his life; the source of the quotation is not given.

[62] L. F. Johnson, The History of Franklin County, Ky. (Frankfort: Roberts Printing Co. Print, 1912), 73.

[63] John Taylor, A History of Ten Baptist Churches, of Which the Author Has Been Alternately a Member: In Which Will Be Seen Something of A Journal of the Author’s Life for More Than Fifty Years. Also A Comment on Some Parts of Scripture, in Which the Author Takes the Liberty to Differ From Other Expositors, Second Edition (Bloomfield, KY: Will. H. Holmes, 1827), 92, reprinted in J. H. Spencer, A History of Kentucky Baptists, (Cincinnati, OH: J. R. Baumes, 1885), 2: 299.

[64] Ermina Jett Darnell, Forks of Elkhorn Church, With Genealogies of Early Members (1946; reprinted, Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1980), 31.

[65] See Ethel Hall Bjerkoe, The Cabinetmakers of America (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1957), 65, which referred to a Porter Clay chair, but spoke erroneously of Clay as of White Hall, Kentucky, the home of General Green Clay. The chair was exhibited at the seminal “Exhibition of Southern Furniture,” Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, 1952.

[66] Dunn, “Dr. Benj. W. Dudley’s Office,” Old Houses of Lexington.

[67] Charles F. Hinds, 175 Year Heritage: History of the First Baptist Church, Frankfort, Kentucky 1816-1991 (Frankfort, KY: First Baptist Church, 1992), 35, 38-39, 57.

[68] First Baptist Church (Frankfort, KY) Records, 1816-1831, Special Collections Manuscript SC-1016, Kentucky Historical Society. Image courtesy of the Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, Kentucky.

[69] Johnson, The History of Franklin County, Ky., 248.

[70] First Baptist Church Records, 5 October 1827.

[71] See Henry Clay Jr., West Point, New York to Henry Clay, 24 October 1829, Papers of Henry Clay (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1984) 8: 117; William C. C. Claiborne Jr. to Henry Clay, 28 November 1829, Papers of Henry Clay, 8: 130; Henry Clay to Henry Clay Jr., Papers of Henry Clay, 8: 131-132.

[72] Kentucky Marriages from The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Company, Inc., 1983), 236. Thomas Marshall Green, Historic Families of Kentucky (Cincinnati, OH: R. Clarke, 1889), 183. Elizabeth Patterson Thomas, “Scotland” (the successor house to Locust Hill), Old Kentucky Homes and Gardens (Louisville, KY: Standard Printing Company, 1939), 54.

[73] She was the daughter of prominent Kentucky pioneer Benjamin Logan and Ann Montgomery. See “Logan,” Kentucky Ancestors, vol. 7, no. 2 (October 1971), 78.

[74] William Barrow Floyd, Matthew Harris Jouett: Portraitist of the Ante-Bellum South (Lexington, KY: Transylvania University, 1980), 36-37. The Jouett portraits, illustrated in William Floyd’s work, are at the Filson Historical Society in Louisville, Kentucky, given by Mr. Evelyn Hardin Sherman.

[75] Anonymous (Henry Clay), “Biographical Sketch of Rev. Porter Clay,” 214.

[76] Richard Lawrence Miller, Lincoln and His World, The Early Years: Birth to Illinois Legislature (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 1: 191-192.

[77] Porter Clay, Frankfort, Kentucky to John J. Hardin, Jacksonville, Illinois, 25 August 1832, one of thirty Porter Clay letters and documents, 1830-1837, in the Hardin Family Papers, Chicago History Museum, Chicago, IL. These papers deal with farm topics—weather conditions, livestock and field crops, sales of land, slaves, and livestock—as well as family and acquaintances and the cholera plague of 1833.

[78] See Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774-1989 (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1989), s.v.

[79] Porter Clay, Locust Hill, to John J. Hardin, Jacksonville, Illinois, 10 November 1833, Hardin Family Papers, Chicago History Museum. Martin D. Hardin had assembled the property in two separate parcels in 1817.

[80] Observer & Reporter (Lexington, Kentucky), 9 January 1834.

[81] Thomas D. Clark, Footloose in Jacksonian America: Robert W. Scott and His Agrarian World (Frankfort: Kentucky Historical Society, 1989), 114-115.

[82] Anonymous (Henry Clay), “Biographical Sketch of Rev. Porter Clay,” 214.

[83] A letter from Porter Clay in Frankfort, Kentucky to John J. Hardin in Jacksonville, Illinois, 7 July 1830, Hardin Family Papers, Chicago History Museum, indicated that Hardin was in Illinois by May of 1830.

[84] Darnell, Forks of Elkhorn Church…, 164. The house, known as the Porter Clay House, stands in 2014 at 1019 West State Street in Jacksonville, Illinois. The house is documented in the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS); available online: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/hh/item/il0224.photos.063364p/ (accessed 5 December 2014).

[85] Porter Clay, Frankfort, Kentucky to John J. Hardin, Jacksonville, Illinois, 28 February 1833; Porter Clay, St. Louis, Missouri to John J. Hardin, Jacksonville, Illinois, 3 May 1833; Porter Clay, Frankfort, to John J. Hardin, Jacksonville, 14 May 1833, Porter Clay, Frankfort, to John J. Hardin, Jacksonville, 6 November 1833, mentioning “Mr. Shryock.” Manuscript letters and transcription, Hardin Family Papers, Chicago History Museum.

[86] Porter Clay, Frankfort, Kentucky to John J. Hardin, Jacksonville, Illinois, 28 February 1834, Hardin Family Papers, Chicago History Museum.

[87] Franklin William Scott, Newspapers and Periodicals of Illinois 1814-1879 (Springfield: Illinois State Historical Library, 1910), 23.

[88] “Porter Clay Rests in Camden Grave: Brother of Illustrious Henry is Buried in Old and Unfrequented Cemetery,” Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock, AR), 23 February 1913.

[89] Jim Lair, “Porter Clay: A Ouachita County Baptist Giant From the Past,” Ouachita County Historical Quarterly, vol. 24, no. 1 (Fall 1992), 12.

[90] Paul M. Angle, “Here I Have Lived”: A History of Lincoln’s Springfield 1821-1865 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1935), 78-79.

[91] Twenty-Third Annual Meeting of the American Colonization Society, 21 January 1841, Henry Clay Presiding (Washington, DC: American Colonization Society, 1841), 7. The Liberator (Boston, MA), 28 June 1839: “Mr. Porter Clay, of Illinois, now an agent of the Colonization Society, had lectured in Greensburg [Indiana] a few days before. He is a brother of the Hon. Henry Clay, and is the same whose name is mentioned in connection with the outrageous case of kidnapping which occurred sometime ago in Jacksonville, the village in which he resides.” The kidnapping relates to the story of two slave children, Emily and Robert Logan, moved to Illinois, a free state, by the Clays. Although the Clays attempted to retain both as slaves, Emily escaped to freedom; Robert was kidnapped and sold back into slavery in Missouri. The Logan name indicates that they were the property of Elizabeth Logan Hardin Clay.

[92] Francis Mason, The Story of a Working Man’s Life (New York: Oakley, Mason & Co., 1870), 128.

[93] The Sun (Baltimore, MD), 18 December 1844.

[94] Thomas Marshall Green, “The Logans,” Historic Families of Kentucky (Cincinnati, OH: Robert Clarke & Co., 1889), 179-183. For the death of Henry Clay Jr., see Zachary Taylor, Agua Nueva, Mexico to Henry Clay, 1 March 1847, The Papers of Henry Clay, 10: 312-313. Porter Clay’s grandson, Porter Clay Taylor, also served in the Mexican War: “Colonel Clay Taylor served in the Mexican War and was a member of Captain Weightman’s company of Missouri light artillery, in which he served for about a year. He was on Kearney’s expedition to New Mexico, and was with Colonel Doniphan on the latter’s march to join General Zachary Taylor at Buena Vista.” History of St. Charles, Montgomery, & Warren Counties, Missouri (St. Louis, MO: National Historical Company, 1885), 1116-1117.

[95] See Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Collection, LC-USZC4-2957 and LC-USZC2-2392. Online: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3g02957/ and http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3b50266/ (accessed 10 December 2014).

[96] Darnell, Forks of Elkhorn Church, 164; also stated in Kerr, History of Kentucky, 3: 4; see also Thomas Hart Clay and Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Henry Clay (New York: G.W. Jacobs & Company, 1910), 20. “Clay Taylor, in a letter to the late Thomas H. Clay, of Lexington, in 1879, said he had often heard his grandfather [Porter Clay] say that ‘he preached the first English sermon ever delivered west of the Mississippi River.’ ” Quoted in Bowmar, “Porter Clay, Henry Clay’s Brother.”

[97] Edward P. Brand, Illinois Baptists: A History (Bloomington, IL: Pantagraph, 1930), 139.

[98] Rev. Patrick Samuel Gideon Watson, “Chapter XLI: Illinois Baptist Preachers, 1835-1840,” Arkansas Baptist History (1855). Watson never fully completed or published his history, but it is now in preparation and accessible on the internet at the Baptist History Homepage; available online: http://baptisthistoryhomepage.com/ar.phillips.co.html (accessed 5 December 2014).

[99] Anonymous, “Porter Clay: The Career of the Brother of the Famous Henry Clay,” undated scrapbook clipping from Ford’s Christian Repository, reprinted in The Ouachita County Historical Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 2 (Winter 1969), 1-2.

[100] The cause of death was said to be “inflammation of the lungs.” “Porter Clay” entry in Illinois Baptist Pastoral Union, 5, unsourced photocopy in Arkansas History Commission files. The Masonic Lodge of Camden passed a resolution mourning Porter Clay’s death, forwarded to Henry Clay on 17 February, see The Papers of Henry Clay, 10: 677. To his wife, Clay wrote on 7 March, “He has gone, poor fellow, where we must shortly follow,” The Papers of Henry Clay, 10: 684. See also Henry Clay’s letter to N. L. Farris of 11 March 1850: “I am very grateful and thankful for the kindness extended by you and others to my lamented brother in his last illness, and for the respect paid to his remains in Camden, by the Masonic Order, and other citizens,” The Papers of Henry Clay, 10: 686. Obituary notice, The Adams Sentinel (Gettysburg, PA), 11 March 1850; Observer & Reporter (Lexington, KY), 13 March 1850; The Courier-Journal (Louisville, KY), 24 February 1896 (soliciting funds for a monument); “Burial Place of Porter Clay, The Iola Register (Iola, KS), 19 April 1913; “Burial Place of Porter Clay,” The Nashua Reporter (Nashua, IA), 22 May 1913; “Henry Clay’s Brother,” The Lima News (Lima, OH), 23 May 1913; “Brother of Henry Clay is Buried in Arkansas,” The Courier-News (Blytheville, AR), 1 October 1930; “Brother of Clay Buried in Arkansas,” The Ogden Standard-Examiner (Ogden, UT), 2 October 1930; “Memories—The Grave of Porter Clay,” The Camden News, 13 December 1969; “Henry Clay’s Brother is Buried in Camden,” The Camden News (Camden, AR), 3 July 1974; Jim Lair, “Porter Clay: A Ouachita County Baptist Giant From the Past,” The Ouachita County Historical Quarterly, vol. 24, no. 1 (Fall 1992), 13.

[101] The winning submission was by architect James Hamilton of Cincinnati. The original watercolor is in Special Collections, University of Kentucky Libraries. See “Henry Clay’s Monument,” Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, vol. 8, no. 9 (August 1855), 121; see also “Design for Clay Monument,” Lexington Democrat (Lexington, KY), 25 July 1903; Burton Milward, “Gothic Temple First Favored as Memorial to Henry Clay,” In Kentucky, vol. 8, no. 2 (Summer 1944), 8-9, 36; Burton Milward, “The Henry Clay Monument” in A History of the Lexington Cemetery (Lexington, KY: Lexington Cemetery Company, 1989), 33-42.

[102] The Courier-Journal (Louisville, KY), of 24 February 1896 carried an appeal from the Rev. W. K. Penrod of Pine Bluff, Arkansas for funds to erect a monument to Porter Clay. “Must his grave at Camden remain unmarked?”; see also “Humble Brother of Henry Clay,” Lexington Leader, 13 March 1913; “Clay’s Brother Died Poor,” New York Evening Post, 18 February 1913; “Many Interesting Stories Found in Old Cemetery; Many Notables Rest in the City’s Oldest Burial Place; Porter Clay, Brother of Henry Clay, Buried Here,” The Camden Evening News (Camden, AR), 16 October 1924.

[103] G. Glenn Clift, Kentucky Obituaries, 1787-1854 (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1979), 200.

[104] Stryker’s American Register and Magazine, vol. 4 (1850), 450.