German-born cabinetmaker Jacob Sass arrived in Charleston in 1773, the same year that Thomas Leitch put the final touches to his panoramic 1774 “View of Charles-Town” (Figure 1).[1] Leitch’s painting provides a unique view of the South Carolina city as 23-year-old Jacob Sass would have experienced it coming into the Charleston harbor for the first time. Sass died in 1836—only a few years after Samuel Barnard completed his 1831 painting of bustling East Bay Street (Figure 2)—and Charleston was a dramatically different city from the colonial port painted by Thomas Leitch sixty years earlier.[2]

Charleston’s cabinetmaking trade witnessed several seismic changes over the six decades that Jacob Sass lived and worked in the city. By the second decade of the nineteenth century, much of the furniture purchased by Charlestonians was no longer made locally. Instead, venture shipments of bureaus, beds, chairs, and other furniture forms frequently sailed down the coast from America’s mid-Atlantic and northern cities—and from overseas—to be sold in the city’s warerooms.[3] The ethnic and regional characteristics of Charleston’s cabinetmakers and the furniture they produced also greatly evolved in the decades after the American Revolution. The furniture made by the descendants and apprentices of those German-born and German-trained cabinetmakers who arrived in the city in the 1760s and 1770s, such as Jacob Sass, became virtually indistinguishable from that of furniture makers who emigrated from the British isles as well as those born and trained in the American South and North.[4]

Amidst this landscape of change, Jacob Sass (Figure 3) emerged as one of the city’s most prominent German-born citizens. During the Revolution he actively participated in the siege of Savannah, serving with Charleston’s German Fusiliers. He was twice elected president of the German Friendly Society, in 1789 and 1805.[5] He served as president of the vestry for St. John’s Lutheran Church for nearly twenty years and was elected to a number of municipal and state offices.[6] Jacob Sass would also become the most successful of Charleston’s Post-Revolution German School cabinetmakers, working in the trade for nearly forty years and rising above nearly two dozen fellow shop masters, journeymen, and apprentices.

There are hundreds of surviving examples of furniture made in Charleston between 1780 and 1820, yet there are only a handful that can be attributed to a specific cabinetmaker from the city’s German community. Despite the volume of material that has been published about Charleston’s furniture and the city’s cabinetmakers—including two major monographs and several significant articles—it is surprising that until now only one desk and bookcase has been positively attributed to the shop of Jacob Sass (Figure 4).[7] Considering the longevity of Jacob Sass’s cabinetmaking business and his distinction among Charleston’s German community, it would be expected that a few notable pieces of case furniture could be attributed to his shop.

This article addresses that dilemma by employing a statistical process known as hierarchical cluster analysis to evaluate surviving Charleston case furniture. Carefully assessing the results of that cluster analysis will produce a number of new furniture attributions to the shop of Jacob Sass as well as a more refined insight into Charleston’s Post-Revolution German School. Perhaps as importantly, by introducing cluster analysis as a tool for categorizing and interpreting large data sets, this article provides decorative arts scholars with an objective methodology that can lead to new understandings and discoveries about object groupings (see Appendix A).

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

Why hasn’t more furniture been attributed to the shop of Jacob Sass? A simple answer is that Charleston’s German School cabinetmakers operating in the city during the last decades of the eighteenth century produced similarly constructed and decorated furniture—and in nearly all instances they did not sign their work.[8] In fact, if it were not for Jacob Sass’s signature (Figure 5) it would be impossible to attribute the desk and bookcase illustrated in Fig. 4 to his shop.

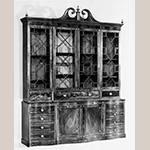

Thomas Savage was the first to identify Charleston’s German School of furniture makers, focusing on those who worked before and during the American Revolution.[9] Primary among these cabinetmakers was Martin Pfeninger, who brought a distinctly Continental style and design to the furniture he made in Charleston. Among the furniture made in Pfeninger’s shop is the iconic Holmes-Edwards library bookcase now displayed in the Charleston Museum’s Heyward-Washington House (Figure 6). Other furniture from Pfeninger’s shop includes a desk and bookcase owned by the Hofyl-Broadfield Plantation, a breakfast table at MESDA, and Colonial Williamsburg’s chest of drawers (Figures 7 through 9).

During the twenty years after the Treaty of Paris officially ended the American Revolution in 1783, there were three German-born and German-trained cabinetmakers documented as shop masters in Charleston: Jacob Sass, Henry Gesken, and Charles Desel.[10] Each of these men immigrated to South Carolina in the 1770s, and most likely they all had worked as journeymen in the shop of Martin Pfeninger through the Revolution. Together, Sass, Gesken, and Desel formed the core of Charleston’s Post-Revolution German School, employing a number of similarly trained journeymen and apprenticing at least ten young men to the trade.

Martin Pfeninger died in September 1782. This is significant because about a year later Jacob Sass first advertised his own shop, in December 1783 (Figure 10).[11] Similarly, Henry Gesken and Charles Desel were not associated with a shop of their own until they formed a partnership in 1784.[12] Neither Sass nor Gesken nor Desel advertised their own businesses until after Pfeninger’s death in 1782 although all three men are documented as cabinetmakers working in Charleston in the 1770s. This evidence strongly suggests that they had worked in Pfeninger’s shop as journeymen.[13]

While all three men may have been at the center of Charleston’s Post-Revolution German School, Sass was obviously the most successful. Sass advertised his shop—located on what is today the south side of Queen Street between Meeting and King—prolifically for over thirty years.[14] Those advertisements reflect a business that was profitable enough to incorporate new products as they became fashionable and to experiment with emerging commercial practices, such as warehousing and auctions.[15] [16] As previously mentioned, Sass served as vestry president of St. John’s Lutheran Church for nearly twenty years.[17] [18] He represented the parishes of St. Philip’s and St. Michael’s in the South Carolina House of Representatives in 1798-1799.[19] In 1799 he was elected to the position of Charleston’s Commissioner of Streets and Lamps and a year later became a commissioner for Sullivan’s Island, a barrier island just outside of the city.[20] He served as a warden and vice president of the Charleston Mechanic Society.[21]

In contrast, Desel and Gesken never advertised their businesses—or at least none of their advertisements survive. Sass was the only one of the three who could read or write. Desel testified in a foreclosure document that he could neither read nor write and when Gesken signed the rules of St. John’s Church he used his mark, not a signature.[22]

Jacob Sass was productive enough on his own that he did not take a partner until 1810 when his son Edward George Sass came of age.[23] Desel and Gesken, however, partnered with each other for five years, from 1784 to 1789.[24]

From 1783 through 1800, Charleston’s Post-Revolution German School grew to include six shop masters, six journeymen, ten apprentices, and four partnerships (Figure 11).[25] This network became even more intricate in the first decade of the nineteenth century as the apprentices of German School shop masters came of age and formed partnerships of their own. Adding to this generational complexity in the 1790s is a significant influx of Scottish journeyman cabinetmakers and those from the American North who intermingled and integrated with Charleston’s German shops, as well as the employment of local non-German apprentices and journeymen that began working with German School shop masters.

Sorting out the furniture produced by the Post-Revolution German School shops is greatly complicated by the fact that there do not seem to be any easily recognizable features to establish what came from which shop. A multitude of anonymous hands worked in numerous shops producing similarly constructed and decorated furniture and very few signed or labeled examples survive.[26] Thus, it is quite understandable why, with only one piece of signed case furniture, scholars and collectors have been hesitant to attempt any attributions to Jacob Sass’s shop based on construction or decoration.

The signed desk and bookcase (Fig. 4) was made for Judge John Julius Pringle in 1794 and resided in the Miles Brewton House on King Street for much of the nineteenth century and at least the first half of the twentieth. Judge Pringle’s daughter-in-law, Mary Motte Alston Pringle, penned an 1876 memorandum to her will that bequeathed to her daughter, Susan Pringle, “the Secretary that stands in the drawing room… given to me by my husband’s father.” The desk and bookcase was most likely the “large mahogany secretary-bookcase” valued at $550 in Susan Pringle Frost’s probate dated 1960.[27]

Could MESDA’s secretary bookcase (Figure 12) also have been made in Jacob Sass’s shop? Obviously the signed desk and bookcase is quite plain while the secretary bookcase is heavily ornamented with veneer, inlaid stringing, and bellflowers, but their proportions are very similar. They are both extremely tall and wide: the desk and bookcase is nearly a foot wider and taller than other desk and bookcases of the period, and the secretary bookcase is only a few inches narrower and shorter.[28] And there are other similarities as well, such as their framed and paneled upper and lower backs, the distinct pattern of the bracket feet featuring a half astragal pendant on the respond, and the plan of the desk interiors and the pattern of the pigeon-hole valences (Figures 13, 14, and 15).[29] [30]

The two pieces had not been linked by scholars in published works. Bradford L. Rauschenberg and John Bivins Jr. documented the unsigned secretary bookcase in The Furniture of Charleston, 1680–1820, but they grouped it with two other pieces made between 1790 and 1800 as the products of an unidentified German School shop (Figures 16 and 17). They made no direct connection between the secretary bookcase illustrated in Fig. 12 and the signed Sass desk and bookcase.[31]

How to move forward? With no other antecedents with signatures to compare, dozens of surviving related unsigned examples, and a complex landscape of potential makers that stretched over a twenty-year period, there is not an established decorative arts methodology that can either confirm or negate a reasonable and rational attribution to the shop of Jacob Sass. Or is there?

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

Biologists and biophysicists have a variety of analytical tools at their disposal for identifying relationships among large populations of similar specimens. Collecting construction variables of case furniture to determine potential relationships among surviving examples is not very different from cataloging the physical traits of individuals to define species and subspecies of organisms or to defining structural similarities amongst different molecular configurations. To that end, an informal probability study was created that included a data set of variables found on case furniture with Charleston attributions.[32]

The probability study recorded twelve construction and decoration variables from a sampling of 130 examples of Charleston case furniture made before 1820.[33] Some of these variables were unique to the signed Sass desk and bookcase (Fig. 4), but most could not be considered significant in a shop with multiple journeymen and partnerships forming and dissolving over time. When analyzed in total across a large sample of furniture, it was hoped that these innocuous variables might reveal some helpful groupings. The twelve variables included:

- Back Construction: Framed and paneled upper and lower case backs OR framed and paneled upper case back with horizontal lower case back boards

- Foot: Straight or canted bracket foot pattern seen on the signed Sass desk and bookcase (indented at bottom and featuring a half astragal at end of responds)

- Dustboards: Full-bottom dustboards, either 3/4 or full depth

- Foot Blocking: Vertical foot blocks resting upon horizontal, abutting flanker blocks that are shaped to the foot responds and mitred at corner

- Bed Blocking: Full-width bed blocks on front and full-depth bed blocks on sides, blocks mitred at front corners

- Drawer Height: Graduated drawers

- Drawer Construction: Drawer backs pass sides; large beveled drawer bottoms set into dadoes in front and sides; nailed at back; boards parallel to front

- Pediment Construction: One-piece dovetailed frame with pediment, cornice, and frieze

- Door Joinery: Door frames are unpinned mortise-and-tenon jointed; corner joints may be mitred or covered with triple stringing or astragal molding

- Desk Interior: Shaped valences, document drawers/prospect sizes, and overall layout seen on signed Sass desk and bookcase

- Secondary Woods: White pine and/or red cedar and/or cypress and/or yellow pine (no tulip poplar)

- Carcass Joinery: Case carcass is dovetailed top and bottom

Each of the variables was then converted into numerical values based on their similarities to the signed Jacob Sass desk and bookcase (the “control” example). Those values were:

2 = a match with the signed Jacob Sass desk and bookcase

1 = not recorded or not applicable[34]

0 = not matching the signed Jacob Sass desk and bookcase

This resulted in a scale of zero to 24, with a score of 24 being an exact match to the signed Sass desk and bookcase.

This probability study showed that ten examples from the survey scored an 18 or above (including, of course, the signed Sass desk and bookcase; see Appendix B). This suggests that nine pieces of furniture analyzed might be related to the signed desk and bookcase. Two of them—MESDA’s secretary bookcase (Fig. 12) and a second desk and bookcase (Figure 18)—matched all twelve variables found on the signed Jacob Sass desk and bookcase.

While an interesting and heartening exercise in applying mathematical analysis to establish potential relationships among decorative arts objects, a more formal and proven analytical tool was required to determine if there was any validity to these groupings. Through the guidance and assistance of Dr. Freddie Salsbury, associate professor of physics at Wake Forest University, whose areas of expertise include computational and theoretical biophysics, the data set of twelve case furniture construction and decoration variables were evaluated and prepared for hierarchical cluster analysis. Just one of many mathematical tools used by scientists and statisticians to identify relationships among populations, hierarchical cluster analysis is a technique with a primary purpose of grouping objects into “clusters” based on attributes, or variables, that make them similar. Those clusters “form groups in such a way that objects in the same group are similar to each other, whereas objects in different groups are as dissimilar as possible.”[35] In other words, the clusters represent examples in the population analyzed that are more closely related to one another than to any other objects in the study.

Cluster analysis is an accepted tool used in biology, paleontology, and archaeology, for analyzing data for oil mining, medical imaging, and even crime prevention. Whenever and wherever there is a need to manage and interpret relationships in “big data” sets, cluster analysis is commonly employed.[36] For researchers in the fields of decorative arts and material culture, the ability to work with large data sets has become an imperative as more and more analog databases, archives, and even monographs are being digitized or are born digitally. A few of the digital resources that can be manipulated and interpreted in ways that would have been unthinkable in an analog world include: Yale University Art Gallery’s Rhode Island Furniture Archive; the Classical Institute of the South’s Gulf Coast Decorative Arts & Fine Arts Database; the Chipstone Foundation and University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Digital Library for the Decorative Arts and Material Culture; and the MESDA Craftsman Database and MESDA Object Database.[37] In addition, large decorative arts data sets are now easily collected by researchers as more and more museums make their collections records and images available online.

Dr. Salsbury’s hierarchical cluster analysis of the Charleston case furniture data set identified fourteen pieces of furniture (cluster G3.3.2.2.2, which included the signed Sass desk and bookcase) as being more strongly related to the signed Jacob Sass desk and bookcase than to any of the other 130 examples of case furniture analyzed (Appendix C). Of those fourteen examples, ten were most relatable to the Sass Shop (the other four will be discussed in detail below). In other words, the computer algorithm had provided a mathematical basis for relating ten pieces of case furniture to the shop of Jacob Sass (including the signed desk and bookcase).

The group of furniture attributed to the Jacob Sass Shop obviously begins with the signed desk and bookcase from 1794 (Fig. 4) and MESDA’s 1790 to 1800 secretary bookcase (Fig. 12). Also included are:

-

• the circa 1790 desk and bookcase (Fig. 16), which sold at public auction in September 2010

-

• the linen press (Fig. 17) in a private collection, which was probably purchased by Nathaniel Heyward in 1789 or 1790 for his East Bay Street townhouse[38]

-

• the desk and bookcase (Fig. 18) in a private Charleston collection[39]

-

• a linen press owned by Drayton Hall (Figure 19)

-

• a linen press (Figure 20) in the Rivers Collection of Charleston[40]

-

• a secretary bookcase (Figure 21) at the Baltimore Museum of Art

-

• the serpentine-front secretary linen press (Figure 22) also in the Rivers Collection[41]

-

• and the Alston family library bookcase (Figure 23) in Yale University Art Gallery’s Garvan Collection[42]

It must be explicitly stated that hierarchical cluster analysis was just one method among several that were employed to support these attributions to the Jacob Sass Shop. It would be foolish to assume that cluster analysis alone can be used to attribute furniture, or any other object, by robotically feeding data into a computer. These ten attributions of furniture to the Jacob Sass Shop were based on a number of observed relationships, including:

• previous attribution to Charleston through provenance, wood usage, and/or style

• dating to the 1780 to 1820 period through style, hardware, provenance, and/or wood usage

• shared variables with the signed desk and bookcase (cluster analysis results)

It is paramount to recognize that attributions based on cluster analysis without supporting evidence are useless because:

Cluster analysis is descriptive… [it] has no statistical basis upon which to draw inferences from a sample to a population, and many contend that it is only an exploratory technique…. Cluster analysis will always create clusters, regardless of the actual existence of any structure in the data.… Only with strong conceptual support and then validation are the clusters potentially meaningful and relevant.[43]

There were numerous considerations made in choosing how to model the Charleston case furniture data, such as how many features or variables to include, what those variables were, and how many were unique to the “control” example (the signed desk and bookcase). In this particular study, hierarchical cluster analysis was intended to define groupings among related examples. In contrast, cluster analysis can also be used as an exploratory tool to classify large amounts of information or populations of objects into manageable and possibly meaningful groups. See Appendix A for more detailed information about cluster analysis and considerations for shaping data sets and using cluster analysis in decorative arts research, as well as more detailed information about the variables chosen for the hierarchical cluster analysis of Charleston case furniture and the resulting data set.

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

As emphasized above, hierarchical cluster analysis was simply one tool among several that were employed to generate the list of ten examples of case furniture attributable to the Jacob Sass Shop. Using the traditional methods of connoisseurship and provenance to further define the group, it is also possible to attribute two tables to the shop of Jacob Sass.

The Sass Shop library bookcase (Fig. 23) was owned by William Alston of Charleston and Georgetown, South Carolina, as was the card table illustrated in Figure 24.[44] [45] Both objects were likely among the household furnishings recorded in the 1840 estate inventory of Alston’s Georgetown plantation house (Figure 25).[46] The inventory listed a “Book case $100,” a “Library containing about 250 books at $1 per,” as well as “1 pair Card Tables $10.”[47] The Sass shop may have produced the library bookcase and card tables en suite with the two tea tables ($12) and a dining table ($40) also listed in Alston’s inventory.[48] This suite of furniture was made in Charleston, most likely between 1791 and 1795, for Alston’s use at the Miles Brewton House at 27 King Street. Following Alston’s marriage to Mary Brewton Motte in 1791, he acquired “the Miles Brewton House (completed 1769) on King Street, arguably Charleston’s most palatial, surviving pre-Revolutionary townhouse. He [Alston] may have commissioned the library bookcase [Fig. 23] for his city residence shortly thereafter.”[49]

Rauschenberg and Bivins suggested the possibility of the Alston library bookcase and card table being part of a larger set based on the similarities of their inlay (Figure 26):

With the exception of seating furniture, no intact matching suites of Charleston neoclassical furniture are known to survive, but there is evidence that they existed. William Alston’s library bookcase [Fig. 23]…has an unusual floral inlay that accents the mitres in the veneered facings of the bookcase and cabinet doors. Virtually the same inlay occurs on the frame of a round card table [Fig. 24] that also has a history of descent from Alston. This table undoubtedly was one of at least a pair… and therefore suggests that Alston’s house at 27 King—or at least his library—was graced with a set of matching furniture.[50]

The card table’s shared provenance and inlay decorations with the Alston library bookcase attributed to Jacob Sass’s shop provides strong evidence to also place the card table in the Sass Shop.[51] [52] The same reasoning provides evidence to attribute a breakfast table in the Kaufman Collection (Figure 27) to the Sass Shop as well. Not only do the inlaid husks, stringing, and floral decorations on the drawer front of the breakfast table match those found on the Alston card table and relate to the bookcase (Figure 28), but all three pieces of furniture once resided in the Miles Brewton House. A label affixed to the underside of the breakfast table reads: “This table came from the old Pringle home at 27 King st. Charleston So. Ca… .”[53] The breakfast table may very well be one of the “2 tea tables $12” recorded in Alston’s 1840 household inventory and part of a Sass Shop suite of furniture produced for the Miles Brewton house that included the library bookcase and card table.[54]

William Alston’s library bookcase also provides support for the speculation that Jacob Sass worked as a journeyman in Martin Pfeninger’s shop in the 1770s and early 1780s. Such a relationship becomes apparent when Pfeninger’s library bookcase (Fig. 6) is compared to the one produced by the Sass Shop (Fig. 23). There are obvious parallels between the two bookcases, especially in their serpentine fronts, floral inlays, and general layout of drawers, cabinets, and decoration. The two library bookcases visually support the theory that Sass had worked in Pfeninger’s shop—a theory that grows stronger when the timing of Sass’s first advertisement, only a year after Pfeninger’s death, is considered.[55]

Here again, cluster analysis can provide mathematical evidence to support a supposition. Based on the cluster analysis data, Dr. Salsbury generated a relationship dendrogram, a diagram in which the identified clusters are plotted geometrically (Figure 29). The more closely the clusters are charted on the dendrogram, the more closely the objects in those clusters are related; the farther apart the clusters appear on the dendrogram, the less related the objects in the clusters are related. In other words, the dendrogram visually represents how strongly or distantly the groupings, or clusters, are related.

In this study, the furniture attributed to Jacob Sass’s shop is shown in cluster number 1, to the far left. The most closely related shop is cluster number 3, which contains much of Martin Pfeninger’s furniture. This establishes that the Sass Shop case furniture has a stronger correlation to that of Pfeninger’s than to any other Charleston cabinetmaking shop. In other words, the dendrogram provides evidence that Jacob Sass had indeed worked in the shop of Martin Pfeninger.

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

Returning to the original cluster analysis groupings (Appendix C), the Sass cluster (G3.3.2.2.2) revealed even more about the Post-Revolution German School than expected. In addition to the ten examples in cluster G3.3.2.2.2 that have been attributed to the Jacob Sass Shop, there were four pieces of furniture that scholars had previously considered to be the product of other cabinetmakers. This is a noteworthy aspect of any cluster analysis that can lead to larger discoveries. The resulting clusters sometimes point to relationships not previously considered. Indeed, the Sass cluster analysis provided support for an argument that those four examples may have been the product of Jacob Sass’s apprentices after they worked in his shop and reflect the acculturation of Charleston’s Post-Revolution German School by the first decade of the nineteenth century.

Two of the examples, a linen press and a secretary bookcase (Figures 30 and 31), might be the work of Jacob Sass’s son, Edward George Sass. While no documentation exists to prove that Edward George Sass apprenticed under his father, it would have been an anomaly for him to train under someone else.[56] Adding to that master-apprentice relationship, Edward George Sass also worked in partnership with his father for five years beginning in 1810. After the partnership of Sass & Son was dissolved in 1815, Edward George Sass established a furniture warehousing business with Andrew Gready, who had no known connection to the Charleston German community prior to his partnership with Edward George Sass.[57]

The linen press and secretary bookcase were possibly made by Edward George Sass and not another of his father’s apprentices, but he would have been quite young to make them, since both pieces stylistically date to 1805 at the latest, when he would have been only 17 years of age. That said, the variegated star on a card table (Figure 32) in a private collection signed “E.G. Sass” and dated 10 October 1811 provides an interesting comparison. Similar stars are found on both the linen press and secretary bookcase (Figures 33 and 34).[58]

Unfortunately, there are no examples of case furniture attributed to or signed by Edward George Sass for comparison, and although the cluster analysis placed the linen press and secretary bookcase in cluster G3.3.2.2.2, no conclusions can be made without further evidence.

The next unanticipated example included in cluster G3.3.2.2.2 is a secretary bookcase currently owned by the Historic Columbia Foundation (Figure 35). Rauschenberg and Bivins related this example to another secretary bookcase (Figure 36) produced by the short-lived partnership of John Michael Philips and John Welch.[59] John Michael Philips, the son of John and Regina Phillips, was baptized at St. John’s Lutheran Church and was a member of the German Friendly Society.[60] Whom he apprenticed under is not known, but it was most likely either Jacob Sass or one of his competitors, Charles Desel or Henry Gesken. It is also unknown where John Welch was born, but he does not seem to have had any connection to Charleston’s German community before working with Philips.[61]

Both of these secretary bookcases have features that are found on Jacob Sass’s work, but there are other details that more closely relate to Massachusetts furniture—especially from the city of Salem—as John Bivins highlighted in his 1997 American Furniture article and in his books with Rauschenberg.[62] Could Welch have been one of those Salem influences on Charleston? Quite possibly.

The fourth example that the hierarchical analysis placed in the cluster G3.3.2.2.2 is a secretary bookcase (Figure 37) that could be the work of Jon Gros or the partnership of Jon Gros and Thomas Lee. Gros was documented as being apprenticed to Jacob Sass in 1794, so it is logical that their work would be grouped together in the cluster analysis.[63]

Rauschenberg and Bivins made a tentative attribution of the secretary bookcase to Jon Gros and/or Gros & Lee by comparing its foot with the one found on Colonial Williamsburg’s secretary linen press signed by Thomas Lee (Figure 38).[64] Historic Charleston Foundation acquired a secretary linen press with dressing drawer (Figure 39) that has the same foot profile (Figure 40)—this example had previously been attributed to an unknown Scottish cabinetmaker in Charleston.[65]

Beginning in 1804, Jon Gros formed a three-year partnership with Thomas Lee, a Scottish-born-and-trained cabinetmaker who immigrated to Charleston shortly before their partnership was established.[66] Thomas Lee signed the base of Williamsburg’s secretary linen press, which is also signed by an otherwise undocumented craftsman named “Grimball.”[67] Could the Williamsburg secretary linen press have been made in Jon Gros’s shop by Thomas Lee shortly after he arrived from Scotland and before he formed a partnership with Gros? It might explain why both Lee and Grimball signed it, since both men may have been journeymen in Gros’s shop.

Also, the gothic drops on the cornice of Williamsburg’s secretary linen press compare favorably to those found on one of the Sass-attributed linen presses (Figures 41, 42, and 43). This gothic decoration was published in the late 1780s on Plate 3 of The Cabinet-Makers London Book of Prices. If the linen press was made while Jon Gros was Sass’s apprentice, then Gros could have easily incorporated the cornice construction and design later into his own furniture.[68] The possibility of Gros being the maker of the secretary linen press was recognized by Rauschenberg and Bivins as well, as they wrote that “Lee’s partnership with Gros is important in regard to the probable blending of German-school and Scots fashions in their work.”[69]

Like Edward George Sass and John Michael Philips, Jon Gros partnered with a furniture maker from outside his local ethnic community. The furniture that those three partnerships produced could reflect an acculturation of these wider influences and mark the tail end of a distinct “German School” in Charleston’s furniture.

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

Among the hundreds of surviving examples of furniture made in Charleston, South Carolina between 1785 and 1820 very few had been attributed to a Post-Revolution German School cabinetmaker. Surprisingly, until now only a single example had been attributed to the shop of Jacob Sass. Drawing on the work of previous scholars and the MESDA Object Database, a large amount of information was collected and then a hierarchical cluster analysis implemented to manage such a sizeable data set. The results of that cluster analysis, in concert with traditional methods, revealed ten examples of case furniture and two tables that can now be attributed to the Jacob Sass Shop.

By carefully interpreting the relationships pinpointed by the cluster analysis and resulting dendrogram, a more nuanced view of Charleston’s Post-Revolution German School is revealed. A bit of light has been shed upon a confusingly complex landscape of shop masters, journeymen, and apprentices; émigrés, natives, and creoles; the formation and dissolution of partnerships; and indoctrination and acculturation of technique and design. A better understanding emerges, suggesting that by the first decade of the nineteenth century the German School furniture of Charleston was speaking less with a Teutonic growl and more with a faint Scottish brogue or the hint of a New England Yankee accent.

While cluster analysis will—and must—never replace connoisseurship as a method of attribution through observation, historical document research, and provenance, it should be considered a powerful tool at our disposal. Just like Ancestry.com has become a proven resource for establishing provenance and Google has allowed for efficient searching of vast amounts of primary and secondary resources, cluster analysis should be considered one technique for managing large data sets and objectively finding relationships among groupings of objects. I hope that this article provides inspiration and a methodological framework for others to adopt cluster analysis into their decorative arts research.

Gary Albert is Editorial Director and Adjunct Curator of Silver & Metals at MESDA. He can be reached at [email protected]

The author wishes to extend appreciation and heartfelt thanks to Brad Rauschenberg and John Bivins. Both men have been instrumental in my education in southern decorative arts and without whom this article would not have been possible. Appreciation is extended to my talented colleagues on the MESDA staff, especially Robert Leath, June Lucas, and Daniel Ackermann, and also those field researchers who contributed to the hundreds of files on Charleston furniture in the MESDA Object Database. Thanks, of course, to Dr. Freddie Salsbury, Associate Professor of Physics, Wake Forest University, for his enthusiasm and efforts in seeing this article to publication. Others who assisted and supported this work and deserve my appreciation and acknowledgment include: Betsy Allen, Gavin Ashworth, David Beckford, Adam Bowett, Andrew Brunk, Russell Buskirk, Tara Chicirda, Dr. Amber Clawson, the Priestly Coker Family, Edward Counts, Brandy Culp, Ron Hurst, Grahame Long, Rob and Jane Pearce, Jim and Harriet Pratt, Sumpter Priddy, the staff and loyal patrons of Recreation Billiards, Tom Savage, Wes Stewart, Dr. Van West, Bill and Patty Wilson, and Phil Zea.

Appendix A: Methodology Considerations for Cluster Analysis

Freddie Salsbury, PhD and Gary Albert

What follows is a general discussion of cluster analysis and its potential application for decorative arts researchers. Nearly every university and many community colleges with statistics or data science programs have a specialist with the skills and software required to execute a cluster analysis. If you are interested in incorporating cluster analysis into your research, you should develop a relationship with a local program or professional statistician who can help you shape your data, identify appropriate variables to include, and conduct a valid cluster analysis.[70]

Cluster analysis is a group of multivariate techniques whose primary purpose is to group objects (e.g., examples, respondents, products, or other entities) based on the similarities across the variables they possess. The primary objective of cluster analysis is to define the structure of the data by placing the most similar observations into groups, or clusters, based upon attributes that make them similar. If plotted geometrically (such as in a dendrogram), the objects within the clusters will be close together, while the distance between clusters will be farther apart.

The term cluster analysis does not identify a particular statistical method or model, as do discriminant analysis, factor analysis, and regression, rather cluster analysis defines a class of techniques of varying complexity. In cluster analysis, one generally does not make any detailed assumptions about the underlying distribution of the data, instead one uses cluster analysis to determine groupings within the data. There are numerous ways you can sort cases into groups; the four most common approaches are hierarchal clustering, k-means clustering, Gaussian-mixture models, and neural network approaches.

Generically speaking, hierarchal clustering produces nested clusters, so one can obtain sets of different clusters depending on how finely one wishes to parse similarity. Nested clusters are commonly used to infer ancestral relationships, and as such were ideal for the Charleston case furniture project.

K-means clustering produces non-nested clusters based upon distances; commonly used to separate set of data into different types without any desire to infer relationship between clusters. Distances need not be the usual Euclidean geometric distances one uses in the real world, but can be any function that defines how different two things are; a metric in the mathematics sense.

Gaussian-mixture models are used to describe data when the data has overlapping distributions and especially when the data is assumed to come from Gaussian distributions. However, any data set that can be described as a sum of Gaussians can be described with a Gaussian-mixture model; the description may require so many Gaussians so as to make the interoperation difficult.

The last class of methods—neural network—are, as the name suggests, used to classify data in a manner inspired by the working of neurons, and are used as non-linear classification methods when there is massive amounts of data, and the features that separate the data are unclear. A prominent recent example is Google’s “Inceptionism” use of a massive neural network to classify images, and then to invert the neural network to identify what features are used to identify specific types images.[71] The choice of a method depends on, among other things, the size of the data file. Methods commonly used for small data sets are impractical for data files with thousands of cases, and the latter two approaches are best when there is significant amount of data.

In summary, clustering can be used to group any type of data into small number of clusters, each of which captures a particular aspect of the data. A researcher may be faced with a large number of observations that can be meaningless unless classified into manageable groups. Cluster analysis can perform this data reduction procedure objectively by reducing the information from an entire population to information about specific groups.

A cluster is a group of similar objects (examples, cases, points, observations, members, customers, patients, locations, etc.). The clusters within the population are grouped according to their similarity in the several dimensions used to define the data, such as features of furniture. Of the different varieties of clustering approaches available, a hierarchical clustering procedure was chosen for the Charleston case furniture data set. This is due to hierarchical clustering producing a set of nested clusters in which each object is progressively nested in a larger cluster until only one cluster remains, and as such relationships between clustering can be inferred and so ancestral-type relationships may be inferred. Hierarchical procedure begins with each object or observation in a separate cluster. In each subsequent step, the two clusters that are most similar are combined to build a new aggregate cluster. The process is repeated until all objects are finally combined into single clusters, and so a hierarchy is defined that goes from a single super-cluster to each data point; i.e., pieces of furniture, comprising a single cluster. The useful information is obtained in-between, in how the clustering divides the data into groups and subdivides these groups.

Cluster solutions can be variable as they are dependent upon the variables used as the basis for the similarity measure. As a result, the researcher must be especially cognizant of the variables used in the analysis, ensuring that they have strong conceptual support. When shaping a cluster analysis, the researcher should ensure that the sample size is large enough to provide sufficient representation of all relevant groups of the population. The researcher must therefore be confident that the obtained sample is representative of the population, and that each sample is correctly described. In the Charleston case furniture analysis, a population of 130 examples of case furniture made between 1720 and 1820 and attributed to Charleston cabinetmakers was selected. The population of furniture was chosen because it was representative of the city’s cabinetmakers’ products but, as importantly, because it was easily accessed with consistent data collected for each example.[72] In a perfect scenario, every researcher would independently and in-person record each example available to them to create their populations; in reality this will be rarely possible to decorative arts scholars, so using secondary sources would be an acceptable alternative.

There is not a standard number for the variables to be recorded and clustered, although ten variables should suffice. The qualities of the variables, not the quantity, is most important. Researchers should consider carefully the variables they will use for establishing clusters. If they do not include variables that are important, their clusters may not be useful. For example, if a ceramics researcher is clustering pottery and does not include information about height or diameter, then size will not be used for establishing clusters.

The goal of the Charleston case furniture cluster analysis—to determine how many natural groups existed among the population based on the signed Jacob Sass desk and bookcase and who belongs to each group—was paramount in selecting the variables for this study. To determine relationships in the population to the signed desk and bookcase, some of the variables chosen were important to that example (paneled upper and lower cases, foot profile, pediment construction, etc.), but most could not be considered significant on furniture made in a cabinetmaking shop with multiple journeymen and partnerships forming and dissolving over time. Conversely, a cluster analysis could be shaped without specific variables to determine if any natural groups existed among the population. This method would be most helpful for those researchers beginning their investigations into a particular region or time period. For example, clustering a population of needlework samplers all made in Maryland between 1750 and 1850 might reveal clusters of samplers for further study.

Determining which variables to record for each example in the population can be more art than science—and will require the most thought by a decorative arts researcher. In principle, cluster analysis can distinguish between relevant and irrelevant variables as irrelevant variables would be uniformly distributed across different clusters, but given the data sizes likely to be available to a decorative art researcher, irrelevant variables are likely to have spurious correlations to relevant variables and will produce “noise” that can interfere with the clustering. Therefore the choice of variables included in a cluster analysis must be underpinned by conceptual considerations. This is very important because the clusters formed can be very dependent on the variables included. In the Charleston case furniture study, the variables were chosen for three primary reasons: 1) because the analysis was conducted to reveal clusters in relation to the signed Sass desk and bookcase, several variables were specific to the desk and bookcase; 2) all of the variables chosen were construction features most consistently recorded in the MESDA Object Database (from which the great majority of the population was taken); and 3) several of the variables were easily recorded from only a photograph (graduated drawers, foot pattern, desk interior plan, etc.) because sometimes a photograph was all that was available.

The selected variables should be based on objective data. For instance, if the clustering is to identify relationships among a population of paintings, then variables such as dimensions, substrates, pigments, or compositional techniques are appropriate. Subjective variables such as mood, shapes of noses, or naïve versus academic technique could result in weak results, especially if the researcher does not collect the data firsthand. Selecting objective variables also allows for later researchers to replicate or build upon the relationships identified in the cluster analysis.

Consistency is the key to strong results. In a perfect analysis, a researcher would identify the cluster variables prior to the collection of data and that researcher would independently and firsthand record each example in the study population to ensure consistency and completeness. In reality, the variables of a decorative arts study may be driven more by accessibility to the objects in the study and how quickly the data set needs to be collected.[73]

This brief discussion of considerations for shaping data for a decorative arts analysis should not be considered definitive or comprehensive. Employing cluster analysis as a decorative arts tool will most certainly require further discussion and trial and error. Above all, establishing a relationship with a statistician, mathematician, or a computational scientist with expertise in clustering analysis within the researcher’s community to assist in identifying appropriate variables and to perform the cluster analysis will ensure strong and accurate results.

Appendix B: Data Set for the Informal Probability Study of Charleston Case Furniture

Construction & Decoration Variables:

| Variable | Description |

| Variable #1 | Back Construction: Framed and paneled upper and lower case backs OR framed and paneled upper case back with horizontal lower case back boards |

| Variable #2 | Foot: Straight or canted bracket foot pattern seen on signed Sass desk and bookcase (indented at bottom and featuring a half astragal at end of responds) |

| Variable #3 | Dustboards: Full-bottom dustboards, either 3/4 or full depth |

| Variable #4 | Foot Blocking: Vertical foot blocks resting upon horizontal, abutting flanker blocks that are shaped to the foot responds and mitred at corner |

| Variable #5 | Bed Blocking: Full-width bed blocks on front and full-depth bed blocks on sides, blocks mitred at front corners |

| Variable #6 | Drawer Height: Graduated drawers |

| Variable #7 | Drawer Construction: Drawer backs pass sides; large beveled drawer bottoms set into dadoes in front and sides; nailed at back; boards parallel to front |

| Variable #8 | Pediment Construction: One-piece dovetailed frame with pediment, cornice, and frieze |

| Variable #9 | Door Joinery: Door frames are unpinned mortise-and-tenon jointed; corner joints may be mitred or covered with triple stringing or astragal molding |

| Variable #10 | Desk Interior: Shaped valences, document drawers/prospect sizes, and overall layout seen on signed Sass desk and bookcase |

| Variable #11 | Secondary Woods: White pine and/or red cedar and/or cypress and/or yellow pine (no tulip poplar) |

| Variable #12 | Carcass Joinery: Case carcass is dovetailed top and bottom |

Scoring:

2 = a match with the signed Jacob Sass desk and bookcase

1 = not recorded or not applicable [74]

0 = not matching the signed Jacob Sass desk and bookcase

Results:

|

MESDA |

Figure No. ** |

Form |

#1 |

#2 |

#3 |

#4 |

#5 |

#6 |

#7 |

#8 |

#9 |

#10 |

#11 |

#12 |

SCORE |

|

S-10890 |

NC-06 |

Library Bookcase |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

18 |

|

D-32530 |

NC-09 |

Secretary Bookcase |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

18 |

|

D-32529 |

NC-08 |

Wardrobe |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

18 |

|

S-2639 |

NC-51 |

Secretary Bookcase |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

17 |

|

S-29209 |

NC-34 |

Secretary Wardrobe |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

17 |

|

S-27079 |

NC-02 |

Triple Chest |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

17 |

|

S-11937 |

NC-11 |

Wardrobe |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

17 |

|

S-8745 |

NC-20 |

Wardrobe |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

17 |

|

S-8996 |

NC-53 |

Wardrobe |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

17 |

|

S-14180 |

NC-49 |

Wardrobe |

2 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

17 |

|

S-2818 |

NC-58 |

Chest of Drawers |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

16 |

|

S-28780 |

CC-32 |

Chest on Chest |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

16 |

|

S-14657 |

CC-44 |

Desk & Bookcase |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

16 |

|

S-13869 |

CC-46 |

Desk & Bookcase |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

16 |

|

S-8010 |

NC-07 |

Secretary Bookcase |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

16 |

|

S-11698 |

NC-29 |

Secretary Bookcase |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

16 |

|

NN-1616 |

NC-18 |

Secretary Wardrobe |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

16 |

|

MK-5171 |

CC-45 |

Wardrobe |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

16 |

|

S-11840 |

CC-06 |

Cabinet on Chest |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

15 |

|

S-8740 |

NC-28 |

Chest of Drawers |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

15 |

|

S-28776 |

CC-17 |

Chest on Chest |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

15 |

|

S-20343 |

CC-34 |

Desk |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

15 |

|

S-2891 |

NC-32 |

Library Bookcase |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

15 |

|

S-30176 |

– |

Secretary |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

15 |

|

S-2422 |

NC-50 |

Secretary Bookcase |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

15 |

|

S-11329 |

NC-37 |

Secretary Bookcase |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

15 |

|

S-8742 |

NC-54 |

Wardrobe |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

15 |

|

S-8014 |

NC-31 |

Wardrobe |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

15 |

|

S-8344 |

NC-33 |

Wardrobe |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

15 |

|

S-30178 |

– |

Wardrobe |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

15 |

|

S-14600 |

NC-43 |

Wardrobe |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

15 |

|

S-29212 |

NC-48 |

Wardrobe |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

15 |

|

S-29200 |

CC-10 |

Chest of Drawers |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

14 |

|

NN-1882 |

– |

Chest of Drawers |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

14 |

|

S-30175 |

– |

Chest of Drawers |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

14 |

|

S-30177 |

– |

Chest of Drawers |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

14 |

|

S-29731 |

NC-17 |

Chest of Drawers |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

14 |

|

S-28775 |

CC-16 |

Chest on Chest |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

14 |

|

NN-1592 |

CC-26 |

Chest on Chest |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

14 |

|

S-28777 |

CC-18 |

Chest on Chest |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

14 |

|

S-29215 |

NC-73 |

Desk & Bookcase |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

14 |

|

S-8005 |

CC-22 |

Desk & Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

14 |

|

S-5532 |

CC-15 |

Dressing Chest |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

14 |

|

S-14250 |

NC-35 |

Secretary |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

14 |

|

NN-1617 |

NC-23 |

Secretary Bookcase |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

14 |

|

S-14656 |

NC-76 |

Secretary Wardrobe |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

14 |

|

S-9126 |

CC-35 |

Wardrobe |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

14 |

|

S-10891 |

NC-26 |

Chest of Drawers |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

13 |

|

S-8043 |

NC-19 |

Chest of Drawers |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

13 |

|

S-14625 |

CC-05 |

Chest of Drawers |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

13 |

|

S-14649 |

NC-47 |

Chest of Drawers |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

13 |

|

S-9094 |

CC-29 |

Chest on Chest |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

13 |

|

S-8787 |

CC-31 |

Chest on Chest |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

13 |

|

S-8166 |

CC-20 |

Desk & Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

13 |

|

S-28778 |

CC-24 |

Desk & Bookcase |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

13 |

|

S-5990 |

CC-25 |

Desk & Bookcase |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

13 |

|

S-9009 |

NC-56 |

Dressing Chest |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

13 |

|

S-8024 |

NC-03 |

Triple Chest |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

13 |

|

S-8237 |

NC-42 |

Wardrobe |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

13 |

|

NN-2534 |

– |

Chest of Drawers |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

12 |

|

S-14610 |

NC-30 |

Chest of Drawers |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

12 |

|

S-5531 |

CC-03 |

Chest of Drawers |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

12 |

|

S-11733 |

CC-03c |

Chest of Drawers |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

12 |

|

S-7418 |

CC-08 |

Chest on Cabinet |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

12 |

|

S-9148 |

CC-19 |

Chest on Chest |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

12 |

|

S-1129 |

CC-07 |

Desk & Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

12 |

|

S-11241 |

CC-21 |

Desk & Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

12 |

|

MK-6621 |

CC-23 |

Desk & Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

12 |

|

S-8000 |

CC-43 |

Library Bookcase |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

12 |

|

S-1594 |

CC-28 |

Library Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

12 |

|

S-29211 |

NC-46 |

Secretary |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

12 |

|

S-8995 |

NC-22 |

Secretary Bookcase |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

12 |

|

NN-2533 |

– |

Wardrobe |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

12 |

|

S-14620 |

NC-69 |

Wardrobe |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

12 |

|

S-9128 |

NC-41 |

Wardrobe |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

12 |

|

NN-2535 |

NC-52 |

Wardrobe |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

12 |

|

S-13561 |

CC-11 |

Bureau Table |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

11 |

|

S-11135 |

NC-66 |

Cabinet on Chest |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

11 |

|

NN-1610 |

CC-48 |

Chest of Drawers |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

|

S-27129 |

NC-27 |

Chest of Drawers |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

11 |

|

S-8782 |

NC-59 |

Chest of Drawers |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

11 |

|

S-8018 |

CC-30 |

Chest on Chest |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

11 |

|

S-21605 |

CC-33 |

Chest on Chest |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

11 |

|

S-14653 |

CC-09 |

Clothes Press |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

11 |

|

S-28781 |

CC-36 |

Corner Cupboard |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

11 |

|

S-15257 |

NC-01 |

Desk & Bookcase |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

11 |

|

S-29208 |

NC-29d |

Secretary |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

11 |

|

S-14607 |

NC-44 |

Secretary Wardrobe |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

11 |

|

S-29214 |

NC-67 |

Wardrobe |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

11 |

|

S-9038 |

NC-70 |

Wardrobe |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

11 |

|

MK-5162 |

CC-45a |

Bookcase |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

10 |

|

S-28770 |

CC-02 |

Bureau Table |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

10 |

|

S-13784 |

CC-14 |

Bureau Table |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

|

S-8329 |

CC-37 |

Corner Cupboard |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

10 |

|

S-17690 |

CC-01 |

Desk |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

10 |

|

S-9138 |

NC-55 |

Dressing Chest |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

10 |

|

S-11271 |

NC-57 |

Dressing Chest |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

10 |

|

S-8526 |

NC-45 |

Secretary Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

|

S-8868 |

NC-63 |

Secretary Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

10 |

|

S-14629 |

CC-04 |

Chest of Drawers |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

9 |

|

S-1267 |

CC-27 |

Chest on Chest |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

9 |

|

S-13800 |

CC-38 |

Corner Cupboard |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

9 |

|

S-14609 |

NC-77 |

Library Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

9 |

|

S-29210 |

NC-36 |

Secretary |

2 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

9 |

|

S-6429 |

NC-74 |

Secretary Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

9 |

|

S-14678 |

NC-39 |

Secretary Bookcase |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

9 |

|

S-14638 |

NC-40 |

Secretary Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

9 |

|

S-8356 |

NC-61 |

Secretary Wardrobe |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

9 |

|

MK-5453 |

NC-71 |

Sideboard with Press |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

9 |

|

S-8202 |

NC-30a |

Wardrobe |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

9 |

|

S-20972 |

– |

Wardrobe |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

9 |

|

S-8045 |

NC-68 |

Wardrobe |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

9 |

|

S-8734 |

NC-16 |

Chest of Drawers |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

|

S-20204 |

NC-72 |

Secretary Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

|

S-8725 |

NC-38 |

Secretary Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

8 |

|

S-8638 |

NC-62 |

Secretary Bookcase |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

8 |

|

S-8365 |

NC-65 |

Secretary Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

|

S-13162 |

CC-12 |

Desk & Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

|

S-28880 |

CC-13 |

Desk & Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

6 |

|

S-15413 |

NC-60 |

Dressing Chest |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

S-9375 |

NC-64 |

Secretary Bookcase |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

S-14671 |

NC-04 |

Triple Chest |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

S-27083 |

NC-75 |

Secretary Bookcase |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

|

S-21103 |

NC-05 |

Desk & Bookcase |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

24 |

|

S-14460 |

NC-25 |

Desk & Bookcase |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

24 |

|

S-15325 |

NC-21 |

Secretary Bookcase |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

24 |

|

D-32526 |

– |

Desk & Bookcase |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

22 |

|

S-27076 |

NC-10 |

Secretary Wardrobe |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

21 |

|

S-16983 |

NC-24 |

Wardrobe |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

21 |

|

D-32528 |

– |

Wardrobe |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

20 |

* MESDA Object Database identification number

** Figure number in Furniture of Charleston, 1680-1820 (Rauschenberg & Bivins, 2003), if applicable

Appendix C: Results of Hierarchical Cluster Analysis of Charleston Case Furniture Data

|

MESDA ID |

Figure |

Form |

SCORE |

Cluster |

Dendrogram |

|

S-21103 |

NC-05 |

Desk & Bookcase |

24 |

G3.3.2.2.2 |

1 |

|

S-14460 |

NC-25 |

Desk & Bookcase |

24 |

G3.3.2.2.2 |

1 |

|

S-15325 |

NC-21 |

Secretary Bookcase |

24 |

G3.3.2.2.2 |

1 |

|

D-32526 |

– |

Desk & Bookcase |

22 |

G3.3.2.2.2 |

1 |

|

S-27076 |

NC-10 |

Secretary Wardrobe |

21 |

G3.3.2.2.2 |

1 |

|

S-16983 |

NC-24 |

Wardrobe |

21 |

G3.3.2.2.2 |

1 |

|

D-32528 |

– |

Wardrobe |

20 |

G3.3.2.2.2 |

1 |

|

S-10890 |

NC-06 |

Library Bookcase |

18 |

G3.3.2.2.2 |

1 |

|

D-32530 |

NC-09 |

Secretary Bookcase |

18 |

G3.3.2.2.2 |

1 |

|

D-32529 |

NC-08 |

Wardrobe |

18 |

G3.3.2.2.2 |

1 |

|

S-29209 |

NC-34 |

Secretary Wardrobe |

17 |

G3.3.2.2.2 |

1 |

|

S-11329 |

NC-37 |

Secretary Bookcase |

15 |

G3.3.2.2.2 |

1 |

|

S-2422 |

NC-50 |

Secretary Bookcase |

15 |

G3.3.2.2.2 |

1 |

|

S-8344 |

NC-33 |

Wardrobe |

15 |

G3.3.2.2.2 |

1 |

|

S-8996 |

NC-53 |

Wardrobe |

17 |

G3.3.2.2.1 |

2 |

|

S-8742 |

NC-54 |

Wardrobe |

15 |

G3.3.2.2.1 |

2 |

|

S-14180 |

NC-49 |

Wardrobe |

17 |

G3.3.2.1 |

3 |

|

S-14657 |

CC-44 |

Desk & Bookcase |

16 |

G3.3.2.1 |

3 |

|

S-13869 |

CC-46 |

Desk & Bookcase |

16 |

G3.3.2.1 |

3 |

|

MK-5171 |

CC-45 |

Wardrobe |

16 |

G3.3.2.1 |

3 |

|

S-8014 |

NC-31 |

Wardrobe |

15 |

G3.3.2.1 |

3 |

|

S-14600 |

NC-43 |

Wardrobe |

15 |

G3.3.2.1 |

3 |

|

S-29212 |

NC-48 |

Wardrobe |

15 |

G3.3.2.1 |

3 |

|

S-8237 |

NC-42 |

Wardrobe |

13 |

G3.3.2.1 |

3 |

|

S-8000 |

CC-43 |

Library Bookcase |

12 |

G3.3.2.1 |

3 |

|

S-8995 |

NC-22 |

Secretary Bookcase |

12 |

G3.3.2.1 |

3 |

|

S-11135 |

NC-66 |

Cabinet on Chest |

11 |

G3.3.2.1 |

3 |

|

S-14638 |

NC-40 |

Secretary Bookcase |

9 |

G3.3.2.1 |

3 |

|

NN-1617 |

NC-23 |

Secretary Bookcase |

14 |

G3.3.1 |

4 |

|

S-10891 |

NC-26 |

Chest of Drawers |

13 |

G3.3.1 |

4 |

|

S-14620 |

NC-69 |

Wardrobe |

12 |

G3.3.1 |

4 |

|

S-27129 |

NC-27 |

Chest of Drawers |

11 |

G3.3.1 |

4 |

|

S-9038 |

NC-70 |

Wardrobe |

11 |

G3.3.1 |

4 |

|

S-8638 |

NC-62 |

Secretary Bookcase |

8 |

G3.3.1 |

4 |

|

S-2639 |

NC-51 |

Secretary Bookcase |

17 |

G3.2.2.2 |

5 |

|

S-27079 |

NC-02 |

Triple Chest |

17 |

G3.2.2.2 |

5 |

|

S-11937 |

NC-11 |

Wardrobe |

17 |

G3.2.2.2 |

5 |

|

S-8745 |

NC-20 |

Wardrobe |

17 |

G3.2.2.2 |

5 |

|

S-2818 |

NC-58 |

Chest of Drawers |

16 |

G3.2.2.2 |

5 |

|

S-28780 |

CC-32 |

Chest on Chest |

16 |

G3.2.2.2 |

5 |

|

S-8010 |

NC-07 |