Southern furniture is one of the most dynamic subjects in American decorative arts research today. Institutions and private scholars alike are actively investigating a wide array of the region’s cabinetmaking traditions, and their compelling discoveries are regularly revealed in new publications and exhibitions. Yet interest in the topic is comparatively recent. Antiquarians began collecting furniture from the North as early as the 1820s, but there was almost no awareness of its southern counterparts before the 1930s. Even then, study of the material would remain sporadic for another thirty years. Although a small core of early-twentieth-century southern dealers and collectors was aware of the South’s cabinetmaking heritage, the rest of the American decorative arts community was convinced that southern furniture makers fashioned nothing more complex than ladder-back chairs and utility tables.

On those rare occasions when exceptional southern goods came to light, furniture historians almost invariably attributed them to other locales. In her 1900 book, Furniture of Our Forefathers, Esther Singleton illustrated an important Virginia chair now recognized as the work of Robert Walker, as well as the famous Holmes family library bookcase by Charleston, South Carolina’s Martin Pfeninger (Figure 1). She noted the objects’ southern histories and acknowledged their quality, but confidently deemed both to be English imports. A southern origin for such objects was simply inconceivable in that day.

Early museum curators and directors thought along similar lines. In 1909, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA) staged Colonial American Furniture and Silver, the nation’s first significant American decorative arts exhibition. Despite the show’s title, however, almost everything displayed was made in the North. Building on the public’s enthusiastic response to the exhibition, the MMA quickly set about forming a permanent collection of America furniture, accessioning a remarkable seven hundred pieces by year’s end. Once again, nearly all was from New England and the Middle Atlantic states. Private collectors such as Henry Ford, Ima Hogg, Maxim Karolik, and Mitchell Taradash followed the same path, as did the leading antiques dealers.

A preliminary spark of interest in the South’s cabinetmaking traditions at last appeared with Paul Burroughs’s publication of Southern Antiques in 1931. Featuring notable objects from Maryland, Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia (Figure 2), the book was a significant first step, but nothing else of that caliber emerged until after World War II. On the commercial front, a few pioneering southern dealers began to search out the region’s furniture in the late 1920s. Patty Anderson, J.K. Beard, Bessie Brockwell, and their peers helped build several private collections in the South, including those of G. Dallas Coons, Caroline Coleman Duke, and J. Pope Nash. However, the client base for southern dealers was probably modest, and at least some of their northern customers purchased southern goods believing them to be long lost northern exports. That was likely the case with John Babcock Morris, an early twentieth-century Connecticut collector who gave a handsome Shenandoah Valley sofa to Historic Deerfield, assuming it to be a good fit for that New England collection (Figure 3). Indeed, institutional acquisition of southern furniture was always inadvertent during these years. A walnut corner cupboard was accessioned by the MMA in 1934 as an example of Pennsylvania work; only in the 1970s was it recognized as a product of Virginia’s Eastern Shore. Similarly, an outstanding Charleston easy chair in the Winterthur collection was purchased for that collection in the belief that it was from Philadelphia (Figure 4).

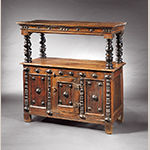

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation was the only major museum intentionally buying goods from the South before the 1960s, and even there, southern furniture was seen as expendable. A now-prized, early eighteenth-century Virginia corner cupboard (Figure 5) acquired by the Foundation in 1928 spent decades as a storage unit in a staff break room, while a graceful Chesapeake sideboard table purchased in 1930 was used as a serving stand in the institution’s busiest restaurant. Records reveal that Foundation leaders often refused to pay the prices asked for significant southern pieces, reflecting the museum world’s low regard for the material. Bessie Brockwell offered the institution an exceedingly rare Virginia court cupboard in the 1930s, but management balked at her price (Figure 6). Like virtually every other museum of that day, Colonial Williamsburg sought cabinet wares from New England and the Middle Atlantic for its exhibition needs. Massachusetts high chests, Rhode Island tea tables, and Pennsylvania easy chairs featured prominently in the Governor’s Palace, the Wythe House, and other exhibition sites. The resulting interiors were beautiful, but they did not represent life in colonial Virginia. Unlike its northern counterparts, Colonial Williamsburg acknowledged the existence of southern furniture, but it nevertheless deemed the material to be of little consequence.

Ironically, one of the principal catalysts for a widespread change in attitudes about southern furniture came at the 1949 Colonial Williamsburg Antiques Forum. Joseph Downs, curator of the MMA’s American Wing, addressed that first Forum audience in a lecture titled “Regional Characteristics of American Furniture.” During the question-and-answer session that followed, a participant asked Downs why his presentation on American regional style had included only goods made in the North. Downs reportedly replied that “little of artistic merit was made south of Baltimore.” Either Juliette Brewer or Eleanor Offutt, both knowledgeable Kentucky collectors and preservationists, purportedly offered a follow-up question. “Mr. Downs,” one of them asked, “do you speak out of ignorance or out of prejudice?” Downs graciously pled ignorance, but his then widely accepted view on the subject, stated in that place to that audience, generated outrage and launched a movement that remains alive today.

A small but determined number of southern furniture proponents almost immediately swung into action and their efforts produced impressive results three years later. The 1952 Antiques Forum was entirely devoted to southern decorative arts and the January issue of The Magazine Antiques was focused on furniture from the South. Most remarkable of all, a loan exhibition of more than 150 pieces of furniture from nine southern states was mounted at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) in Richmond. Curated by Helen Comstock, the installation was jointly sponsored by the VMFA, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, and The Magazine Antiques. Seldom had three such prominent organizations come together for such a massive project in such short order. It was the beginning of a new age in southern furniture scholarship, but why had it taken so long to reach that point?

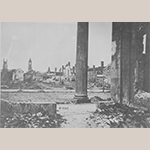

Dismissal of the South’s furniture history is but one by-product of sectional differences that reached fever pitch during and after the Civil War. By the middle of the nineteenth century the North was characterized by large urban centers, modest farms, industrial production, and a free labor force. The South, on the other hand, was a mainly rural realm with only a few large cities, a multitude of farms and plantations, and millions of enslaved men and women. The tensions created by these differences had played out since the late eighteenth century, often at the federal government level. A multitude of sins was committed by parties on both sides, but for many years each region held its own in the national sociopolitical partnership. That balance was erased with the disastrous Civil War and its outcome. Like the losing side in any military conflict, the South—and perceptions of it—were forever altered. In physical terms, destruction in the region reached levels never before seen in North America (Figure 7). Economic devastation was widespread and even basic resources became scarce or nonexistent. The emotional and intellectual impact on the southern populace was profound. Compounding these conditions was the postwar posture of the national government, which treated the South as a vanquished enemy. Decades of punitive Reconstruction politics and fiscal manipulation by an often vengeful congress contributed to grinding southern poverty that lasted until the early twentieth century. The South was, in a sense, economically and culturally banished.

The region’s isolation and disgrace took many forms. Even history books were altered. Before the war, the full American story was conveyed in most schoolbooks, but afterward the South often was marginalized. For example, earlier publications correctly cited Jamestown, Virginia, as the first permanent English settlement in America, but after the war many books reassigned that honor to Plymouth, Massachusetts. Through negative attitudes reflected in revisionist texts, hostile newspaper articles, and even derisive popular entertainments, generations of Americans grew up learning that little of consequence happened in the “backward” region below the Mason-Dixon Line. Small wonder, then, that mainstream early-twentieth-century collectors, scholars, and curators doubted the existence of important southern furniture.

Fortunately, advocates for the study of southern cabinetmaking were more than ready to change the worldview of the subject by the middle of the twentieth century. On the institutional front, the Baltimore Museum of Art published Baltimore Furniture: The Work of Baltimore and Annapolis Cabinetmakers from 1760 to 1820 in 1947, but a body of independent scholars was also bent on spreading the word. Georgia’s Henry Green and South Carolina’s E. Milby Burton were among the most active proponents. Burton’s 1955 Charleston Furniture was a groundbreaking work filled with outstanding examples of cabinet wares from that city (Figure 8). However, it was Frank Horton who came to be seen as the dean of the budding movement. Horton and his mother, Theo Taliaferro, were established dealers in southern decorative arts, but the germ of a new idea was growing in Horton’s mind. By 1960 he and Taliaferro determined to establish a museum dedicated solely to the exhibition of goods made in Maryland, Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. It would be based in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where Horton was leading the preservation of original Moravian buildings at recently established Old Salem. Horton’s Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) debuted in 1965 and, over the next few decades, it radically changed perceptions of southern material culture.

Not content with the mere collection and exhibition of decorative arts from the South, Horton and colleagues Carolyn Weekley, Bradford Rauschenberg, and John Bivins launched MESDA’s revolutionary research program in 1972. Working with dedicated volunteers, they transcribed and cross referenced hundreds of thousands of artisan- and object-related facts from early southern newspapers, court records, vestry books, and other primary sources, producing an unparalleled research tool that continues to grow today as the MESDA Craftsman Database. Next Horton and his team initiated field work during which representatives tracked down southern-made objects, recording images, construction details, and provenance for each, which became the core of the MESDA Object Database. In order to more broadly share the findings of these efforts, they established the Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts (JESDA) in 1975. These and other details of Horton’s personal and professional story are thoughtfully chronicled in a 2006 American Furniture essay by Luke Beckerdite (and Penelope Niven’s biography in the Summer 2001 issue of JESDA), but the point is this: Frank Horton’s brainchild transformed the landscape for those interested in southern material culture.

In the wake of these developments, the dam on southern furniture history was finally breached, and a torrent of published research poured forth in several distinguishable phases over the next thirty-five years. Readers were served the initial findings in a number of articles that represented the first efforts at reconstitution of shop groups. These studies showed how the widely scattered works of long dead artisans could be reassembled through methodical scrutiny of the decorative and structural details recorded in the MESDA Object Database. The results were impressive. Digesting the new findings, the American furniture community began to grasp for the first time the unsuspected quality, quantity, and variety of early southern cabinetmaking. A sampling of subject matter from articles written in the 1970s and 1980s is illustrative.

In 1976 Betty Dahill published findings on the Sharrock family of joiners and carpenters in northeastern North Carolina. Despite their proximity to the Atlantic coast and the city of Norfolk, Virginia, the Sharrocks built case goods with a character all their own (Figure 9). The same year John Bivins, one of the South’s most brilliant material culture historians, published an insightful survey of furniture made by Moravian artisans in Salem, North Carolina (Figure 10). He showed with clarity how northern European craft traditions were transplanted almost unaltered to the North Carolina Backcountry. Two years later readers were treated to Ann Dibble’s prophetic research on seating furniture from the Fredericksburg area in northern Virginia (Figure 11). The boldly formed Georgian chairs, so different from other American seating, were unmistakably the products of a single, then unidentified shop.

In 1979 John Snyder published a study of furniture by the enigmatic northern Virginia joiner John Shearer. The scale, ornament, and especially the message-laden inlays on his furniture baffled modern observers (Figure 12). Three years later, Luke Beckerdite documented William Buckland and William Bernard Sears, who produced astounding rococo woodwork and furniture to match for houses along Virginia’s lower Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers. Horton also carried on research in the midst of his administrative duties. Among his discoveries was English cabinetmaker William Little, who worked briefly in Norfolk, Virginia, and Charleston, South Carolina, before moving to an isolated area of south central North Carolina. There he made distinctly non-rural furniture that combined British form and construction with Norfolk and Charleston ornament (Figure 13). One of the things that struck readers of these and other articles was the fact that the furniture in question often bore little resemblance to its counterparts from the North. Instead, it displayed a character all its own that was, in hindsight, a clear reflection of the peoples, places, and times from which it sprang.

These and other articles were precursors to a spate of book-length studies on southern cabinet wares, beginning in 1976 with Henry Green’s Furniture of the Georgia Piedmont. As noted earlier, the first important volume on southern furniture was published in 1931 and just two others had appeared before Green’s work. In short, only four books on the subject emerged in forty-five years, but a host of new publications was at last in the offing. In 1979, Wallace Gusler produced his path-breaking Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, 1710–1790, the first book to rely extensively on structural analysis for reuniting shop groups. It was filled with neat and plain furniture that clearly illustrated Virginia’s British cabinetmaking traditions. Gusler was followed in 1982 by James Melchor, Gordon Lohr, and Marilyn Melchor’s Raised Panel Furniture from the Eastern Shore of Virginia, 1730–1830, which provided the furniture world with its initial look at that area’s distinctive paneled and polychromed tradition. Two volumes on Maryland furniture followed in 1983 and 1984, respectively: William Voss Elder and Lu Bartlett’s John Shaw: Cabinetmaker of Annapolis and Gregory Weidman’s Furniture in Maryland, 1740–1940: The Collection of the Maryland Historical Society. Five years later Bivins authored his comprehensive Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, 1700–1820, reconstructing a dozen shop groups. In 1997 Jonathan Prown and the present author wrote Southern Furniture: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection, 1680–1830, exploring more than 180 objects in depth. And Bivins and Rauschenberg debuted Furniture of Charleston, 1680–1820 in 2003, revealing that cosmopolitan city’s impressive rococo and neoclassic furniture.

To no one’s surprise, all of these publications were generated by southern scholars and institutions. There was still little interest in the subject beyond the region, but a glimmer of change came with the 1980 publication of Wendy Cooper’s In Praise of America: American Decorative Arts, 1650–1830. Cooper was one of the first scholars to author a book that dealt with all American furniture, both northern and southern, and she did so with an unbiased eye. She observed that “Only a limited number of southern-made objects have been identified, but many of those that are known…exhibit a…sense of good design and proportion.” Cooper assessed an early Virginia tea table as “visually enchanting,” and noted that “The rarity of any early southern furniture makes this table’s existence extremely important, yet the object clearly stands on its own merit” (Figure 14). Unfortunately, her approach was still rare outside the South.

Institutional acquisition of southern furniture was also confined to the South during these years, but newly published research shaped most choices for southern curators. At MESDA, work leading to the publication of Furniture of Charleston brought several highly important Lowcountry objects into the permanent collection, including the earliest signed example of Charleston furniture (Figure 15). The same happened at Colonial Williamsburg, where research for The Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia resulted in acquisition of a perfectly preserved Williamsburg china table and other objects of similar significance. Later, preparation for Southern Furniture caused the Foundation to broaden its collecting parameters, resulting in purchase of a Lowcountry clothespress attributed to the shop of Jacob Sass and a remarkable tall clock from the mountains of southwestern Virginia (Figure 16). Other southern institutions followed suit, and notable objects entered the collections of the High Museum of Art, the VMFA, the Baltimore Museum of Art, and Bayou Bend, as well as a number of southern state historical societies. In a similar vein, a new generation of private southern collectors began to aggressively seek the region’s furniture. During this period both institutions and private collectors often worked with a group of astute southern dealer-scholars that included Luke Beckerdite, Deanne Levison, Milly McGehee, and Sumpter Priddy, among others.

In the mid-1990s a new phase in southern furniture research emerged as scholars began fine tuning the efforts of earlier decades. Examples of such work include Betsy Davison’s decoding of the curious messages left by John Shearer on many of his products. Tara Gleason Chicirda demonstrated that a body of furniture firmly attributed to several Williamsburg shops was instead made by James Allan, Thomas Miller, and others working in Fredericksburg, Virginia (Figure 17). Robert Leath proved that furniture long ascribed to Williamsburg’s Peter Scott was the work of Robert Walker near Port Royal, Virginia (Figure 18). And the present writer confirmed that Scott was instead responsible for a body of previously unattributed tables and case pieces with histories in the Williamsburg area (Figure 19). Key to many of these discoveries was access to more recently available web-based research tools that allowed scholars to locate crucial primary sources so obscurely archived that they would likely never have been found through normal avenues of inquiry.

The most recent phase of southern furniture research surfaced in the late 2000s and is largely focused on previously unstudied or understudied southern cities and districts. Examples abound. Sumpter Priddy and Ann Steuart conducted an in-depth investigation of objects and documents associated with Washington, D.C., persuasively attributing a body of striking neoclassic furniture to that city’s Henry Ingle, William Waters, and William Worthington (Figure 20). June Lucas did remarkable work on the culturally complex North Carolina Piedmont, uncovering new shop groups, expanding old ones, and convincingly ascribing them to previously obscure artisans such as Jacob Sanders of Montgomery County (Figure 21). Perhaps most eye opening of all are new findings on the furniture of the Inland South and the Lower South: Kentucky, Tennessee, Upcountry South Carolina, the Georgia Piedmont, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Museum professionals such as Dale Couch at the Georgia Museum of Art and Daniel Ackermann at MESDA are breaking new ground in these places, as are several private scholar/collectors, among them Mary Jo Case, Tracey and Kim Parks, Mack and Sharon Cox, Jack D. Holden, and H. Parrott Bacot. Findings from these studies are appearing in article form and in impressive books such as The Art of Tennessee, Furnishing Louisiana: Creole and Acadian Furniture, 1735–1835 and Collecting Kentucky, 1790–1860. In a curious twist of fate, it took southern furniture scholars from the Atlantic coast almost as long to recognize the merit of inland southern cabinetmaking traditions as it did for northern scholars to acknowledge the South.

With regard to institutional collecting in this most recent phase of southern furniture studies, institutions in the South naturally remain at the leading edge. Both MESDA and Colonial Williamsburg have added remarkable examples of Georgia, Tennessee, and Kentucky furniture to their permanent collections (Figures 22 and 23), and Williamsburg acquired its first significant piece of Louisiana furniture (Figure 24). However, for the first time a few northern institutions have begun to purposefully collect southern furniture. At the forefront is the Winterthur Museum in Delaware, which acquired three noteworthy Virginia blanket chests in 2010 and 2011: a refined Eastern Shore model; a previously unrecorded instance of Johannes Spitler’s work; and a chest from Wythe County with a rich yellow ground (Figure 25). No one would have predicted such developments twenty-five years ago.

Clearly southern furniture scholarship has come a very long way since the publication of the first book on the topic nearly eighty-five years ago. Progress in the last the last three decades alone is staggering. Yet there is still much to learn, and with the advent of new research technologies, fresh findings in southern furniture will continue to appear in rapid fashion. Much of the credit for both past and future discoveries lies directly or indirectly with Frank Horton and MESDA. On this fiftieth anniversary of the museum’s creation, there is, indeed, much to celebrate.

Ronald L. Hurst is Vice President for Collections, Conservation, and Museums and The Carlisle H. Humelsine Chief Curator at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Bibliography

Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore Furniture: The Work of Baltimore and Annapolis Cabinetmakers from 1760 to 1820 (Baltimore, MD: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1947).

Luke Beckerdite, “William Buckland and William Bernard Sears: The Designer and the Carver,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, vol. 8, no. 2 (November 1982).

Luke Beckerdite, “The Life and Legacy of Frank L. Horton: A Personal Recollection,” American Furniture, 2006, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2006).

John Bivins Jr., “Baroque Elements in North Carolina Moravian Furniture,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, vol. 2, no. 1 (May 1976).

John Bivins Jr., The Furniture of Coastal Carolina, 1700–1820 (Winston-Salem, NC: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1988).

Paul Burroughs, Southern Antiques (Richmond, VA: Garrett & Massie, 1931).

E. Milby Burton, Charleston Furniture (Charleston, SC: The Charleston Museum, 1955)

Benjamin Hubbard Caldwell, Robert Hicks, and Mark Scala, Art of Tennessee (Nashville, TN: Frist Center for the Visual Arts, 2003).

Tara Gleason Chicirda, “The Furniture of Fredericksburg, Virginia, 1740–1820,” American Furniture, 2006, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2006).

Wendy Cooper, In Praise of America: American Decorative Arts, 1650–1830 (New York: Knopf, 1980).

Betty Dahill, “The Sharrock Family: A Newly Discovered School of Cabinetmakers”, Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, vol. 2, no. 2 (November 1976).

Elizabeth A. Davison, The Furniture of John Shearer, 1790–1820: “a true North Britain” in the Southern Backcountry (Lanham, MD: AltaMira, 2011).

Ann W. Dibble, “Fredericksburg-Falmouth Chairs of the Chippendale Period,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, vol. 4, no. 1 (May 1978).

William Voss Elder and Lu Bartlett, John Shaw: Cabinetmaker of Annapolis (Baltimore, MD: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1983).

Henry D. Green, Furniture of the Georgia Piedmont Before 1830 (Atlanta, GA: High Museum of Art, 1976).

Wallace B. Gusler, Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, 1710–1790 (Richmond, VA: Virginia Museum of Art, 1979).

Jack D. Holden, H. Parrot Bacot, Cybéle T. Gontar, Brian J. Costello, and Francis J. Puig, Furnishing Louisiana: Creole and Acadian Furniture, 1735–1835 (New Orleans, LA: Historic New Orleans Collection, 2010).

Frank L. Horton, “William Little, Cabinetmaker of North Carolina,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, vol. 4, no. 2 (November 1978).

Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Southern Furniture 1680–1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection (New York: Harry Abrams for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1997).

Ronald L. Hurst, “Peter Scott, Cabinetmaker of Williamsburg: A Reappraisal,” American Furniture, 2006, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2006).

Genevieve Baird Lacer, Libby Turner Howard, and Bill Roughen, Collecting Kentucky, 1790–1860 (Louisville, KY: Cherry Valley Publications, 2013).

Robert A. Leath, “Robert and William Walker and the “Ne Plus Ultra”: Scottish Design and Colonial Virginia Furniture, 1730–1775,” American Furniture, 2006, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2006).

June Lucas, “Paint-Decorated Furniture from Piedmont North Carolina,” American Furniture, 2009, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2009).

James Melchor, Gordon Lohr, and Marilyn Melchor, Eastern Shore, Virginia, Raised Panel Furniture, 1730–1830 (Norfolk, VA: Chrysler Museum, 1982).

Penelope Niven, “Frank L. Horton and the Roads to MESDA,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, vol. 27, no. 1 (Summer 2001).

Sumpter Priddy and Ann Steuart, “Seating Furniture from the District of Columbia, 1795–1820,” American Furniture, 2010, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2010).

Bradford L. Rauschenberg and John Bivins Jr., The Furniture of Charleston, 1680–1820 (Winston-Salem, NC: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 2003).

Esther Singleton, The Furniture of Our Forefathers (New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1900).

John J. Snyder Jr., “John Shearer: Joiner of Martinsburgh,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, vol. 5, no. 1 (May 1979).

Gregory Weidman, Furniture in Maryland, 1740–1940: The Collection of the Maryland Historical Society (Baltimore, MD: Maryland Historical Society, 1984).

Alice Winchester, ed., “Furniture of the Old South, 1640–1820” The Magazine ANTIQUES, January 1952.