The rope and tassel inlay found on early-nineteenth-century furniture made in East Tennessee’s Nolichucky River Valley reflects the region’s ever-evolving cultural identity. Patriotism, religion, ethnic diversity, migration, and the physical environment all played a role in the changing discourse of material life in the first decades of Tennessee statehood. The cabinetmakers of the rope and tassel school created furniture that spoke to the social and material aspirations of Nolichucky River Valley residents as expressed through Republican and agrarian symbolism.

As an example of the imaginative entrepreneurship that formed the material landscape of the early American Backcountry, the rope and tassel tradition reflects a particular time and place. This article provides such context by introducing readers to East Tennessee’s rope and tassel tradition and the shop of Hugh McAdams, the first cabinetmaker who made examples of rope and tassel furniture. The intent is to employ that context and attribution to create a metaphorical “cultural palette,” enabling more complete understanding of the inlaid imagery and symbolism found on the rope and tassel school furniture of Tennessee’s Nolichucky River Valley.

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

For a generation of decorative arts scholars, this ornately inlaid furniture group of East Tennessee had only been identified as the “rope and tassel” school. Until recently there had not been any artisanal attributions to associate a cabinetmaker’s name with the group. Three challenges may provide explanations: First, few American cabinetmakers in the early nineteenth century signed their finished products.[1] Second, by the turn of the twentieth century many of Tennessee’s earliest families had relocated farther west, taking much of their material world with them. In fact, examples of rope and tassel school furniture had moved as far west as Missouri.[2] Third, the physical evidence could be misleading. In more than one instance, missing or replaced feet and cornices had slowed or confused a piece’s inclusion in the group.

Several cultural organizations displayed rope and tassel school furniture in exhibits and included it in catalogues. In 1971 the Tennessee Fine Arts Center at Cheekwood in Nashville first presented multiple rope and tassel furniture alongside one another in “Made in Tennessee: An Exhibition of Early Arts and Crafts” and the companion catalog.[3] That same year, Ellen Beasley included examples in her article as part of the special “Antiques in Tennessee” issue of The Magazine ANTIQUES.[4]

Subsequently, in the 1980s, the state’s decorative arts scholars and collectors joined forces to produce the seminal monograph The Art and Mystery of Tennessee Furniture and its Makers through 1850 authored by Derita Coleman Williams and Nathan Harsh and edited by C. Tracey Parks (Figure 1).[5] The book catalogues all of the then-known examples of the rope and tassel school and includes an extensive enumeration of Tennessee cabinetmakers based on the 1820 Census of Manufactures and newspaper advertisements.

Namuni Hale Young presented several rope and tassel school pieces in her 1997 catalog of the exhibition “Art & Furniture of East Tennessee” at the Museum of East Tennessee History in Knoxville.[6] That same decade the William King Museum in Abingdon, Virginia spearheaded a regional fieldwork initiative. The museum’s director, Betsy White, documented decorative arts craftsmen from southwest Virginia and northeast Tennessee.[7] The fieldwork project culminated in a database of makers and objects as well as an exhibit and book that share the title Great Road Style: The Decorative Arts Legacy of Southwest Virginia and Northeast Tennessee (Figure 2).[8] In 2013 White enumerated the documented artisans from Great Road Style in her second book Backcountry Makers: An Artisan History of Southwest Virginia and Northeast Tennessee (Figure 3).[9]

Attributions to potential rope and tassel school cabinetmakers were not posed in any of these previous publications and exhibitions. In 2015, forty-five years after the “Made in Tennessee” exhibit in Nashville, my doctoral dissertation included the first attribution of an example of rope and tassel school furniture to a specific shop: that of Nolichucky River Valley cabinetmaker Hugh McAdams (1772–1814).[10] In addition, my research revealed that Hugh McAdams’s brother Robert (1782–1823); one of Hugh’s sons, Thomas Cunningham McAdams (1806–1881); a nephew, William Slaughter McAdams (1809–1842); and a grandson, Samuel Bryson McAdams (1845–1900), also made furniture.[11]

The McAdamses had not been identified as furniture makers in any of the previous studies. Why, given that the lengthy record of Hugh McAdams’s 1815 estate sale itemizes numerous cabinetmaking tools and supplies, did he not surface previously as a cabinetmaker?[12] A possible answer might be that Hugh McAdams never advertised in print as newspapers were scarce in the Nolichucky River Valley during the early nineteenth century. Another reason for McAdams escaping notice might be that the 1820 Census of Manufactures focused predominantly on craftsmen in urban and small town settings. McAdams, while living and working in proximity to the town of Jonesborough, was located in a more rural setting along Big Limestone Creek (Figures 4 and 5).[13]

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

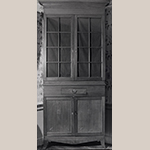

Hugh McAdams (1772–1814) has a familial connection to one of the most iconic examples of rope and tassel school furniture: the Murray corner cupboard (Figure 6). The cupboard was acquired by MESDA from the eminent Tennessee collector Mary Jo Case, who had purchased it from a descendant of the cupboard’s original owner, Ephraim Murray (1765–1835), who probably purchased this rope and tassel corner cupboard from the McAdams Shop not long after Murray moved to Jonesborough from Baltimore, Maryland.[14] [15] While no receipt for the purchase of the cupboard has been located, Ephraim Murray’s earliest Tennessee papers were recovered from the cupboard’s drawers. Hugh McAdams’s youngest daughter married into the Murray family, with whom the corner cupboard remained for nearly two hundred years, likely in the same house for the majority, if not the entirety, of its existence.[16]

A second archetypal example of rope and tassel group furniture is the Brabson corner cupboard (Figure 7) and it also has a provenance with ties to Hugh McAdams. Currently in a private collection, the inlay on this cupboard’s lower doors is easily recognizable because it is featured on the dust jacket of The Art and Mystery of Tennessee Furniture (Fig. 1). The cupboard descended in the Brabson family of East Tennessee and was purchased by a private collector at an auction near Bowmantown in Washington County, Tennessee.[17] Located a few miles west of Jonesborough, Bowmantown was named for Hugh McAdams’s acquaintance Elias Bowman (1746–1829), the Revolutionary War veteran who settled the area.[18] The Brabson family lived along Big Limestone Creek for a time and court records reveal that Hugh McAdams had negotiated to sell a parcel of land along Big Limestone to Thomas Brabson (1763–1844).[19]

The Murray and Brabson corner cupboards exhibit many of the characteristic design features identified with rope and tassel school furniture. They employ walnut as the primary wood with tulip poplar for secondary woods; the inlay is probably holly.[20] The cupboards feature cove cornices. Both have two glazed upper doors with eight lights each. The Murray cupboard has central waist molding above three adjacent drawers with rectangular stringing, corner shaded quarter fans, and central escutcheon pinwheels. The Brabson cupboard has only a central waist molding, but no drawers; however, it retains its original scrolled skirt with bracket feet while the Murray cupboard’s skirt and feet are replaced.[21] Both cupboards feature two adjacent lower doors with recessed panels. All of these construction elements create a canvase for elaborate pictorial inlays.

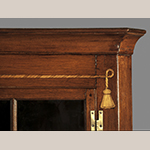

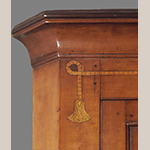

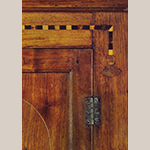

The cornice inlay of the Murray cupboard features a lightwood central wheat stalk framed by downward curved tulips wrapped around pinwheels; the flowers stem from a vine extension of the rope inlay that terminates in a tassel at each end of the frieze (Figures 8 and 9). Like the Murray cupboard, the barber pole inlaid ropes on the Brabson cupboard loop at the corners. A major distinction between the Brabson cupboard and the Murray cupboard is that the rope inlay terminates in floral tassels rather than more traditionally shaped tassels (Figure 10).

The lower doors on the Murray cupboard have central leaves encircled by half-ovals and box stringing with quarter fan shapes in a checkered pattern with traces of original green dye (Figure 11). The Brabson cupboard also has inlaid quarter fans and rectangular stringing that frame compass stars (Figure 12). The stars’ dual colors give them a three-dimensional appearance while octagonal barber-pole forms enclose the compass stars.

The likelihood that Hugh McAdams made the two cupboards is supported by the tools and supplies sold at his 1815 estate auction (see Appendix A). In total, McAdams’s estate included a large amount of plank, unfinished cut lumber ready for use in building homes or furniture including eleven “piles” of plank, 650 feet of one-inch plank, and other miscellaneous plank.[22] Besides numerous “piles” of plank, McAdams also had patterns (presumably for inlay motifs), one marking tool, a veneering saw used to cut thin slices from plank for inlay, and a gluepot—all necessary for advanced inlay work. His estate sale further included approximately forty-five planes; one turning lathe; five chisels; five gouges; three hammers; seven dovetail, tenon, and hand saws; and two workbenches.

McAdams died intestate, leaving no will, yet the items sold at his estate auction document the large amount of lumber and specialized tools required to produce the case furniture with intricate inlays found in the rope and tassel group.[23] In addition, the multiple workbenches suggest an operation with multiple craftsmen working alongside McAdams. Further investigations confirm the likely presence of journeymen working in the Hugh McAdams Shop as well as family members who were also trained in the cabinetmaking trade.

A search of the records for Greene and Washington counties in the MESDA Craftsman Database provides evidence that his was the most likely shop at that time and place from which the two cupboards were produced. The MESDA Craftsman Database records 247 carpenters and cabinetmakers actively working in the Nolichucky River Valley between 1800 and 1850.[24] The primary documentary sources for each of those 247 carpenters and cabinetmakers were scrutinized. Estate inventories, advertisements, and wills enabled the elimination of individuals who did not possess the requisite tools to create the furniture of the rope and tassel group.[25] The list was then limited to only those cabinetmakers working in the Nolichucky River Valley between 1800 and 1830 when the rope and tassel furniture was made.

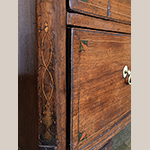

A candidate quickly surfaced in Thomas K. Kinnard, who opened a shop in the “cabinet line” in 1819 in the heart of Jonesborough on Chestnut Street.[26] In one of the earliest advertisements from the region, Kinnard stated he “hopes to give general satisfaction by having work executed in the neatest style and latest fashion.”[27] A Kinnard desk (Figure 13 and 14) is one of the few examples of Tennessee furniture from this early period that possesses a maker’s signature (Figure 15).[28] The desk has distinctive features such as a fallboard with a scribed, inlaid open-winged eagle perched on a (replacement) veneer medallion (Figure 16), an interior with graduated drawers with astragal rectangular stringing, and a shaped skirt with veneered medallions.

Despite working as a cabinetmaker in the right place at the right time to have made the Murray and Brabson corner cupboards, Kinnard’s use of cockbeading, veneered insets, and shaped side skirts depart from the two cupboards as well as the other known furniture in the rope and tassel school. Thus Kinnard can be eliminated as a possible maker.

Ultimately, examination of records in the MESDA Craftsman Database combined with provenances and the tools itemized in the 1815 estate sale led to the conclusion that the Murray and Brabson corner cupboards were the product of Hugh McAdams’s cabinetmaking shop on Big Limestone Creek.

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

The most detailed account of Hugh McAdams’s life occurred after his death in 1814. His estate auction in 1815 (Appendix A) illustrates his possessions—and those of his wife Isabella (1776–1855)—falling into three principal categories: home goods, farm tools, and cabinetmaking tools.[29] Two enslaved individuals, Moses and Sarah, are also itemized as property sold at the auction. When pieced together, McAdams’s estate auction and other documents can be used to reveal the cabinetmaker’s social and material world.

Hugh McAdams was born in Pennsylvania or southwest North Carolina (Figures 17 and 18), a child of Scotch-Irish parents drawn to the region by economic and social opportunity.[30] It is unclear where Hugh’s father, Thomas McAdams (1750–1811), lived and worked prior to 1790, the year that the first Federal Census recorded him Rutherford County, North Carolina. At the time, Rutherford County encompassed the far western reaches of North Carolina, which included land that is today in the state of Tennessee.[31] The location of the McAdamses in the Blue Ridge Mountains suggests that the family was already familiar with life in small mountain communities even before relocating to Tennessee. Thomas and his wife, whose name is unknown, had three sons: John, Hugh, and Robert (see Appendix B for a McAdams family tree). According to the 1790 census, the eldest son, John, lived nearby with a wife (whose name is also unknown). The death of Thomas’s wife may have prompted the family’s relocation from Rutherford County to the Washington District of the Nolichucky River Valley.

The Washington District and its growing market offered opportunity for young men like the McAdamses. The region also held promise for older men such as Thomas McAdams, who hoped their sons would inherit large tracts of land. The three brothers and their father arrived in the Nolichucky River Valley sometime during the 1790s.[32] Their tract bordered both Big Limestone and Mill creeks, which gave the McAdamses access for irrigation and travel.

Evidence of Thomas McAdams’s occupation also does not survive. The furniture-making training of Hugh and his younger brother Robert remains elusive. If Thomas was a cabinetmaker, it is possible that he trained his sons himself. If he was not a cabinetmaker, it is equally conceivable that Thomas’s community connections arranged apprenticeships for Hugh and Robert in North Carolina or Tennessee. Whether farmer or cabinetmaker, waterways such as the Nolichucky tributaries benefitted the McAdams family economically.

Why did the McAdams family situate along Big Limestone Creek in particular? The McAdamses capitalized on local geography and natural resources when they located their shop.[33] The Broyles family saw mill was on the banks of Little Limestone Creek and may have provided the McAdams cabinetmaking shop with the cherry, walnut, and tulip poplar lumber they required.[34] When Limestone Creek ran at full strength, it was navigable by flatboat and could transport finished products farther west.

The first reference to Hugh McAdams in Tennessee reflects his independent status as an adult: he is recorded in Washington County, Tennessee on the 1797–1798 “list of taxables” in Captain Joseph Duncan’s Company. During his militia service, Hugh McAdams met men like the brothers Elias and John Bowman, Andrew and Joseph Duncan, and David and Alex Stuart.[35] As previously mentioned, Elias Bowman was the namesake of the community, Bowmantown, where the Brabsons lived with their rope and tassel corner cupboard (Fig. 7).

Hugh McAdams also served in the militia alongside Samuel Bryson (d.1816) from Virginia, who played a significant role in Hugh’s future family life.[36] In 1800, only two short years after the men met, Hugh married Samuel’s sister, Isabella Bryson.[37] Although the couple lived in Washington County, the court of Greene County granted their marriage license, which illustrates the permeable nature of administration in early Tennessee. Hugh and Isabella Bryson McAdams had five children: Margaret (1802–1832), Mary (1804–died before 1870), Thomas Cunningham (1806–1881), Samuel Bryson (1809–1894), and Jane (1811–1871) (see Appendix B).

In 1811 Thomas McAdams died and bequeathed his eldest son John, “the plantation whereon I now live containing one hundred and thirty acres which land is situated on both sides of mill creek.”[38] Hugh and Robert each received $50 in cash or livestock from Thomas’s “legacy.”[39] In 1803, Hugh and Robert McAdams had purchased adjacent tracts of land (100 acres each) along Big Limestone Creek and thus had their own property at the time of their father’s death.[40]

Robert McAdams married Mary Slaughter (1776–1851) in 1799 and the couple had one child, William Slaughter McAdams (1809–1842).[41] During his brother’s estate sale, Robert purchased typical cabinetmaking items such as nearly 700 feet of one-inch plank, one sash saw (used to cut frameworks for glass panes in windows or doors), one tenon saw (a fine-toothed saw that produced joints to be mortised), and a dovetail saw (see Appendix A).[42] He also purchased more technical tools including one veneering saw, clamps used to hold glued inlay in place, and a conk shell that was probably a pattern for inlay. Most significantly for making a potential attribution to the rope and tassel furniture group, Hugh’s estate also included a “profile machine,” also purchased by Robert, that might have been used to outline portrait profiles or busts, such as the one seen on the “profile” desk at the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library (see Fig. 54).[43]

Hugh’s estate sale links another Nolichucky furniture maker with the McAdams Shop. The multiple workbenches sold at Hugh’s estate sale suggest that there were other craftsmen working alongside him. Samuel Bruen purchased the greatest volume of carpentry tools from Hugh’s estate.[44] When Bruen died in 1816, less than a year after the estate sale, Hugh McAdams’s wife, Isabella, served as “Administratrix” of Bruen’s estate, further cementing a relationship. Bruen’s brief inventory included joiner’s tools, some plank, livestock, and farming equipment.[45] He may have been an itinerant journeyman cabinetmaker that lived and worked with the McAdams as Bruen had no family or property at the time of his death.[46]

Another Nolichucky cabinetmaker, Joshua Greene, was one of the earliest woodworkers documented in Washington County and may have also worked with the McAdamses. Greene lived along Little Limestone Creek, placing the craftsman in close proximity.[47] Greene’s 1807 probate inventory details an extensive collection of carpentry tools and, like many households by the first decade of the nineteenth century, included a “corner cupboard.”[48]

Little to nothing is known about the McAdamses’ cabinetmaking operation before Hugh’s death. Business was most certainly interrupted when both Hugh and Robert served in the militia during the War of 1812. Hugh was commissioned a sergeant in Captain John Porter’s unit, which was part of the 5th Regiment of the East Tennessee Militia lead by Colonel Edwin Booth.[49] The 5th Regiment marched from Knoxville in 1814 and spent the duration of the campaign in Mobile, Alabama where General Andrew Jackson feared that if the British arrived the Chickasaw and Cherokee would join them.[50] Private Robert McAdams served in Captain William Lauderdale’s unit lead by Colonel Edward Bradley’s 1st Regiment of Tennessee Volunteer Infantry.[51] In 1813, men from Tennessee’s militia, including Bradley’s regiment, participated in the Battle of Talladega where American troops confronted the Red Stick Creek faction that had besieged the United States-allied Creeks at Alabama’s Fort Leslie.[52] Robert was fortunate to survive the battle as the Tennessee militia suffered heavy casualties.[53]

It is quite possible that Sergeant Hugh McAdams died of a disease contracted while on campaign in Alabama. The cause of his death was not recorded in 1814, but many companies encountered widespread illness in camp, especially in New Orleans. Often worsened by severe weather and poor camp conditions, diseases like dysentery, typhoid, pneumonia, and malaria (among others) ran rampant.[54]

Isabella McAdams did not record the emotional impact of her financial and material insecurity that resulted from her widowhood, although she likely enjoyed familial support from her brother, the unmarried Samuel Bryson, and the extended McAdams family. Hugh McAdams’s religious beliefs may never be discovered, but his final resting place and that of other family members is Fairview Cemetery, located four miles north of Jonesborough.[55] In the early nineteenth century Fairview was the largest cemetery in Washington County and from its beginning the resting place of diverse congregations including Presbyterian, Methodist, and Quaker.[56] By 1830, Isabella and her daughter, Jane, were members of the Presbyterian Church in Limestone.[57]

After Hugh McAdams’s death, his family moved forward with their lives. As a woman of the frontier, Isabella McAdams had few illusions about widowhood. In fact, when she purchased the furniture at Hugh’s estate sale in 1815 she may have already had a new home in mind—less than two months later she married Joseph Hale on Christmas Eve 1815.[58] Hugh and Isabella’s five children (all still under the age of ten in 1815) joined Hale’s household and the couple subsequently had a daughter, Louisa Hale (1817–1850).[59]

Hugh McAdams’s death also significantly impacted the lives of his slaves, Moses and Sarah. Slave trading between residents in the Nolichucky River Valley had forced Moses and Sarah, to move at least five times during seven years (1809-1815). [60] First from Frank Allison to Joseph Duncan in 1809, two months later in the new year of 1810 to Elias Bowman, and some time prior to 1814 to McAdams.[61] In 1815, James Nelson purchased Sarah and Moses from Hugh’s estate.[62]

Following the death of their brother, Robert and John McAdams, pursued different paths. Robert remained in the Nolichucky River Valley and continued to work with wood until at least 1822, as indicated by coffin sales.[63] He died a year later in 1823. Ultimately, John outlived his two younger siblings and moved west. He could be the same John McAdams recorded in Middle Tennessee’s Monroe County during the 1840 Federal Census. Although final inheritance issues were not settled for twenty years after Hugh’s death, John McAdams figured prominently in the suits and countersuits between Hugh’s (then adult) children and their stepfather, Joseph Hale, who was reluctant to part with their valuable, landed inheritance along Big Limestone Creek.[64]

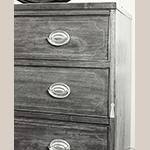

The children of Hugh and Isabella McAdams came of age during the second quarter of the nineteenth century, a time of growing industrialization nationally and rapidly improving transportation methods in East Tennessee. As a result, some local and regional cabinetmaking shops ceased operations as their patrons increasingly went to urban centers for their furniture or had it shipped to them directly from factories in northern cities.[65] Evidence of the McAdamses continuing a cabinetmaking tradition in the Nolichucky River Valley, however, demonstrates that regional cabinetmaking did not come to a complete halt. In her will, Hugh McAdams’s daughter, Margaret McAdams, requested that her brother Thomas Cunningham McAdams, “when it may Suit his convenience he make two good bureaus and give one to [his wife] Cynthea and [her sister] Mary Stephenson.”[66]

The eldest son of Hugh McAdams, Thomas Cunningham McAdams lived at Locust Mount in Washington County, where he served as the community’s postmaster and worked as a farmer, owning at least two slaves.[67] His sister’s request for him to make two bureaus suggests that Thomas may have continued the family’s cabinetmaking tradition. The fact that Thomas was asked to make two chests of drawers would indicate he possessed at least rudimentary joinery skills if not the capability to make decorative inlay. His sister’s caveat, “When it may suit his convenience,” suggests that cabinetmaking for Thomas was a secondary endeavor. If he had learned to craft furniture, however, Thomas could have taught one of his sons the rope and tassel tradition as well: The family’s oral history suggests that his son, Samuel Bryson McAdams (1845–1900), was also a cabinetmaker in the latter half of the nineteenth century.[68]

A more conclusive familial link to a continued McAdams cabinetmaking tradition is Hugh’s nephew, William Slaughter McAdams, son of Robert. A late-nineteenth-century genealogical history includes a description of William as working in Washington County as a cabinetmaker and maintaining a small farm.[69] Based this information, the McAdams cabinetmaking tradition in East Tennessee could have included William working under or with his uncle Thomas alongide cousin Samuel Bryson.

While extant furniture and documents do not disclose the existence of a furniture making shop run by the second and third generations of McAdamses on Big Limestone Creek, it is clear that the style of furniture made in East Tennessee (and elsewhere) did change in the 1830s and 1840s. Scholar Michael Ettema, however, argues that historians in the twentieth century overestimated the impact technological inventions had on the antebellum furniture making industry.[70] Supporting Ettema’s argument are the recognized East Tennessee cabinetmakers John Earhart Rose (Figure 19) and John Christian Burgner (Figure 20).[71] While the region’s rope and tassel inlay may have given way to more current tastes and fashions, those subsequent McAdams woodworkers, along with Rose and Burgner, were continuing a rich tradition of handcrafted furniture made in East Tennessee through to the end of the nineteenth century (Figure 21).

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

The McAdamses and other associated-yet-unidentified East Tennessee rope and tassel school cabinetmakers selected motifs from their cultural palette, mixing and adapting inlaid imagery and symbols to complete furniture commissions.[72] These motifs were born from each cabinetmaker’s own aesthetic, experiences, and training. In this way, the rope and tassel furniture of the Nolichucky River Valley is both “a site of cultural construction and a field for personal expression.”[73]

Large case furniture forms—corner cupboards, desks, chests of drawers, and a sideboard—served as blank canvases for the school’s cabinetmakers.[74] Cornices, stiles, doors, and drawers all offered a vehicle of expression for consumers and makers that reflected “Fancy,” a term meant to “manipulate the viewer’s perceptions and activate the sense of wit and whimsy.”[75] After the American Revolution, interior décor in urban as well as rural spaces embraced Fancy’s richness of color and visual excesses.[76] Artists and craftsmen at the turn of the nineteenth century did not immediately shed symbols associated with the Revolution; rather, American artisans created playful interpretations of neoclassical designs and those inspired by luxurious textiles, such as ropes and tassels. The tassel, in particular, became a visual cue that intimates affluence through textile trimmings.

American artists sometimes painted tassels in portraits to highlight the sitter’s wealth. Itinerant artist Charles Peale Polk, for instance, used a tassel to frame the sitter in his oil on canvas portrait of Peter Lauck in 1799 (Figure 22).[77] Born in Pennsylvania, Lauck lived in Winchester, Virginia for most of his adult life.[78] The draped cord and tassel served as a mechanism to frame the background view of Lauck’s landholdings. Additionally, artist John Drinker painted Mrs. John Briscoe’s oil on canvas portrait around 1800 (Figure 23). The tassel in Drinker’s portrait frames Mrs. Briscoe’s accessories and is offset by the torus base of a column obscured in the upper right hand corner by the drapery.[79]

In early-nineteenth-century East Tennessee, where new residents needed material goods to fill newly constructed interiors, McAdams and other rope and tassel school cabinetmakers answered the market’s call. The school’s inlaid motifs fall into three categories: neoclassical, agricultural, and patriotic. Its inlaid symbols consist of diamonds, quarter fans, compass stars, vines, birds, bellflowers, and the group’s epoynymous motif, the rope and tassel.

These individual inlaid motifs of the rope and tassel school accentuate the clean lines, restrained embellishments, and regular proportions in early neoclassical furniture along the Great Wagon Road.[80] It is the irregular combinations of those inlaid motifs, however, that result in the school’s distinctive cultural palette. In addition, the pure abundance of decoration of the rope and tassel school sets it apart from other rural Tennessee furniture traditions, generally recognized for their “simplicity” of decoration (Figures 24 and 25).[81]

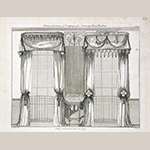

An understanding of passementerie, the art of textile trimmings, may help to better understand this execution of rope and tassels in wood. Tassels, typically associated with textiles, might be considered a surprising choice for two-dimensional wooden inlay but textile specialist Nancy Welch eloquently lauds tassels because they “provide a glimpse of the range of human creativity unburdened by the need for function.”[82] In this way, tassels embody a freedom that imparts power.[83] Such capacity for expression was recognized in the mid-eighteenth-century by Thomas Chippendale, who illustrated tassels on bed hangings and window treatments that clearly correlated tassels with luxury in a gothic bed canopy (Figure 26).[84] Subsequent design works, like Thomas Sheraton’s 1793 The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book, also exhibited tassels on bed hangings and dressing tables (Figure 27).[85]

Although the rope and tassel school’s inlay adaptations are conspicuous in their absence of swag or drapery, they accurately reflect the composition of real-life textile trimming, having the four primary components: a cord for suspension, “head” or loop, “waist” or knot that holds the fringe in place, and “skirt” or fringe.[86] Like the tassels, the inlaid cords or ropes found on the Nolichucky River Valley furniture resemble their passementerie antecedents. The predominant “rope” is an inlaid barber pole pattern, alternating parallelograms of light and dark shades. In some cases, the scribed lightwood inlay still retains its original natural dyes. The looped, barber pole ropes on the only known rope and tassel sideboard (see Fig. 59) and the Murray corner cupboard (Fig. 6) resemble one another and characterize the group’s most distinguishing feature. Other rope and tassel school corner cupboards are not looped at the corners but instead have right-angle corners and feature a square-patterned rope (for example, see Fig. 46).

All of the inlaid decoration on this furniture grouping should be seen as purely creative. The inlay’s primary purpose is adornment, not function. Although Sheraton argued in 1803 that inlay was no longer in style, Hugh McAdams and other rope and tassel cabinetmakers found a way around the very things Sheraton lamented: expense and decay.[87] First, they used more durable, locally sourced, and inexpensive woods like tulip poplar and holly, while Sheraton specifically referenced mahogany, which was costly and less durable.[88] Second, a significant expense associated with inlay was the time consuming application of many especially small pieces to make up a larger design. For example, the checkerboard pattern of the Murray cupboard’s quarter fans could have required up to thirty-two individually dyed and applied pieces (Figure 28). Hugh McAdams, however, chose to scribe the checkerboard pattern onto one larger piece of inlay that appeared to be thirty-two smaller pieces; thereby he saved time and money.

Painted furniture and natural dyes experienced a revival in the early nineteenth century and rope and tassel furniture is characterized by red and green dyes on lightwood inlay (see Fig. 52).[89] During this time, furniture needed to complement Fancy-painted interiors or be lost amid the vibrant backgrounds. Bright colors added a greater depth to the scribed lines on inlay; however, today, the appearance of color varies since some pieces (such as the Murray corner cupboard; see Figure 29) were refinished during their respective lifetimes while others (such as a desk [Fig. 51] and chest of drawers [Fig. 64]) retain their vibrant color.

Hugh McAdams may have popularized inlaid rope and tassel motifs in East Tennessee, but he was certainly not the first to decorate furniture with them. The motif seems to have begun in Baltimore and moved down the Great Wagon Road to the Nolichucky River Valley where it found its greatest expression. For instance, a series of Baltimore card tables (Figure 30), probably by the same urban cabinetmaking shop in operation between 1775 and 1799, form a prominent group of urban inlaid Federal furniture.[90] Recognized today as representative of Baltimore inlay, each leg has three clustered tassels suspended from barber pole cords.[91] The motif is often repeated on multiple sides of respective legs (Figure 31).[92]

Moving farther south, rope and tassel motifs also appear in Virginia furniture. The MESDA Object Database records an 1810 corner cupboard (Figures 32 and 33) with lower recessed paneled doors that feature lightwood tassel inlay suspended from astragal stringing with fleur delis corners.[93] Another form from Virginia, a chest of drawers, illustrates a more restrained tassel on either stile suspended from a ball (Figures 34 and 35).[94] Based on provenance and shared motifs, this group has been labeled the “Rockbridge County Tassel” Group.[95]

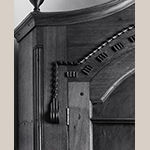

A corner cupboard much closer to the rope and tassel region may be the earliest version of a cupboard adorned with a variant of the rope and tassel across its cornice. Attributed to Greene County, Tennessee, the cupboard (Figures 36 and 37) was made between 1790 and 1800. This corner cupboard has a broken scroll pediment with central urn finial, an applied carved rope and tassel, upper arched eight-light doors, fluted quarter columns, waist molding surrounds three central drawers; and while there is no figured skirt, the cupboard rests on ogee bracket feet.[96]

Items like these antecedents represent the design aspirations and inheritances of the Nolichucky River Valley’s residents. In fact, Ephraim Murray, original owner of the McAdams corner cupboard in Fig. 6, was born and lived in Baltimore for thirty years before moving to Jonesborough. He and his family must have been familiar with Baltimore neoclassical furniture styles and quite possibly the tassel inlay being produced by the city’s cabinetmakers. Together, the men and women of East Tennessee generated a spirited economy and a more permanent community after statehood. Rural homes were not devoid of refinement; rather, people developed their own interpretations of taste for architecture, furniture, and art.

Nature shaped their daily lives during the nineteenth century. As a result, motifs associated with agriculture flourish within the rope and tassel group. Wheat stalks and wheat stalk heads bedeck the Murray corner cupboard cornice (Figure 38) and vines climb up a chest of drawers (see Fig. 65) and across a corner cupboard (Fig. 42). Additionally, the Murray cupboard’s lower recessed panel doors have inlaid, scribed, wheat stalk heads arranged in a quatrefoil (Figure 39) that is referenced by the inlaid pointed oval seen on a sideboard (see Fig. 61). Upturned, delicate bellflowers on two examples are nearly identical in that two petals cradle a protruding pistil. Finally, one of the smallest inlay details, young buds is particularly apt for the burgeoning communities of the Nolichucky River Valley.

Another prominent agricultural motif is the “gamecock,” or rooster (Figure 40). Of the five cupboards with birds, four are gamecocks and one is more ambiguous, categorized at different times as a “bird of prey”.[97] The birds are often applied to the recessed paneled doors at a skewed angle. In the case of the gamecocks (typically skewed backwards) this serves to emphasize their claws, perhaps even suggesting an imminent strike. In the case of the “bird of prey” (skewed forward), its angle suggests it is soon to take flight, although its wings remain closed.

The “gamecock” corner cupboards of the rope and tassel group were produced between approximately 1815 and 1825 (see Figures 41 through 50) and often considered wholly separate from the furniture attributed to the McAdamses in Washington County.[98] Construction and decorative techniques, however, suggest that Hugh McAdams, his family members, or men that worked in his shop (like Samuel Bruen and Joshua Greene) possessed the skills, materials, and regional vocabulary to have made gamecock cupboards.

All of the gamecock corner cupboards have cove cornices, waist beveled molding, and lower paneled doors. Like the cupboards in the McAdams group, the doors of gamecock cupboards are thin and mortise-framed. Some have upper eight-light doors, broken pediments, and three waist drawers (two of which are faux drawers). Upper paneled doors have central inlaid bird framed by oval stringing. Lower paneled doors have central inlaid diamond or bird framed by astragal or oval stringing. Scribe lines on the lightwood inlay were sometimes executed after the pieces were adhered to the larger case, a technique not seen on McAdams Shop inlay.[99]

One gamecock corner cupboard (Fig. 41) has the upper eight light doors and waist drawers of cupboards attributed to the McAdams Shop and, simultaneously, the gamecock motif on lower paneled doors framed by astragal stringing. The placement of the vine and berry across the cornice is the same as other rope and tassel motifs; however, the “rope” in this case is vine and berry that frames the upper eight-light doors with floral “tassels” (Fig. 42).

Furniture scholars Wendy Cooper and Lisa Minardi trace the origins of over 125 examples of line and berry inlay, created by compass, and on multiple forms that pre-date the American Revolution.[100] In Tennessee, single or double “berries” are dispersed along the line, but Pennsylvania examples boast “three tightly clustered berries.”[101] The floral tassel, gamecock motif, and vine and berry inlay illustrate how many differing regional inspirations were available on the palettes of Nolichucky River Valley cabinetmakers.

A highly embellished gamecock corner cupboard (Fig. 43) that descended in the Dykes family of Hawkins County, Tennessee, has a broken scroll pediment, eight-light upper doors, double waist molding that frames three waist drawers (central working drawer flanked by two faux drawers), recessed-panel lower doors, and the original molded base. Inlaid motifs include three sets of rope and tassels: one chevron pattern rope across the cornice terminates on the stile in the uppermost light with scribed tassels; and, the other two barber pole ropes are inlaid directly onto the door rails while the scribed tassels descend into the second light (Fig. 44). The chevron rope is made of two barber pole ropes inverted against one another to create the chevron pattern. The drawer fronts have four quarter fans each and the lower recessed panel doors have central inlaid “bird of prey” framed by tricolor squared “rope.”

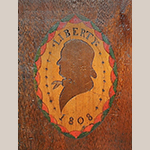

Agricultural symbols represented patriotism as well as prosperity. As primary author of the Declaration for Independence, Thomas Jefferson envisioned an agrarian republic in America where white freeholders earned prosperity from successful agriculture. In the first decade of the nineteenth century, patriotic themes permeated American material culture. It is logical, then, that a veteran of the War of 1812 such as Hugh McAdams, who was raised on the frontier of the new Republic, celebrated America via his craft. The most obviously patriotic motif is that of the open-winged eagle on the slant board of the “profile” desk at The Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, so named for the prominent inlaid bust on the prospect door (Figures 51 and 52). The desk’s open-winged eagle represented the majestic native bird heralded as the national symbol of America. Stars surrounding the eagle correspond to the seventeen states in 1808 of the American union.

Attributed variously in the past to Virginia, Pennsylvania, and, most recently, Tennessee, the “profile” desk represents the shared stylistic and construction influences of the Great Wagon Road.[102] Remnants of natural dyes are still vibrant in the inlay throughout the desk, including on the eagle and quarter fans (Figure 53). The interior prospect door boasts an inlaid silhouette of a man, framed by dyed inlay, stars, and the words “Liberty 1808” (Figure 54) . The date and seventeen stars on the fallboard suggest that the silhouette might be that of James Madison.[103] Elected in 1808 as the fourth President of the United States, Madison served as chief executive during a time when America was comprised of seventeen states. A silhouette of Madison by Joseph Sansom’s (Figure 55), when compared against the desk’s inlaid profile, demonstrates visible consistencies in dress.[104] Silhouettes were fashionable at the time and artists such as Sansom recorded profiles of both illustrious and less well-known individuals.[105] Silhouette artists often used a physiognotrace, also known as a profile machine, to produce their work.[106] Hugh McAdams’s profile machine, which his brother Robert purchased at the estate sale, may have been the tool that created the silhouette for this desk.[107]

The journey of a second rope and tassel school desk (Figure 56) from Tennessee to a Kentucky collection remains a mystery. A clue is an interior signature, “Josiah Thompson,” probably an early owner of the desk (Figure 57). By 1870, Thompson lived along the same tributary of the Nolichucky, Big Limestone Creek, as Hugh McAdams.[108] The desk’s fallboard is devoid of inlay; however, the drawers have inlaid fluted quarter fans with rectangular stringing. Canted lamb’s tongue stiles boast S-curve ribbon that extend approximately a third of the stile’s length. The upper third of the stile has two insets, enclosed diamonds that reference quatrefoils on other pieces (Figure 58).

First appearing in the 1770s, the sideboard quickly became a pronunciation of class for wealthy owners and appears in the Backcountry by 1800.[109] The only example of a rope and tassel group sideboard (Figure 59) was recorded in the 1980s at Trace Tavern Antiques in Nashville, Tennessee, and has an early-twentieth-century recovery history in Shelby, North Carolina.[110] The sideboard was sold to an unknown party and only recently was identified in a private Nashville collection.[111]

The side bays of the Trace sideboard may have, at one time, had doors that closed to cover the stacked drawers; yet, there is no evidence of the various compartments ever having locks.[112] The front four legs have scribed inlaid rope (Figure 60) suspended from horizontal banding on the curved side rails and rope inlay on the front rail. Curved banding frames the eight flared tassel ends found on the fronts and sides of the legs for viewing from multiple perspectives. Above the tassels, a variant of the group’s quatrefoil (Figure 61) is also repeated on multiple sides of the stiles. With two points in an enclosed pinched oval that is shaded with scribed diagonal lines, they resemble those on the Murray corner cupboard (Fig. 6).[113] The sideboard is further decorated with lightwood astragal banding on the top drawer, dramatically offsetting the two wood colors. The current owner states that green dye was present before the sideboard was refinished in the last decades of the twentieth century; however, no trace of color survives today.[114]

Two chests of drawers, or bureaus, associated with the rope and tassel group were acquired by independent scholar, furniture historian, and private dealer Anne McPherson.[115] Like Winterthur’s “profile” desk, the chest of drawers illustrated in Figures 62 and 63 was acquired from a Virginia antiques shop.[116] The second chest of drawers (Figures 64, 65, and 66) was purchased from an antiques dealer who had discovered it in Missouri.[117] Such a western recovery locale for an East Tennessee piece of furniture is not surprising when considering that William Slaughter McAdams and other family members moved to Missouri after 1830 and may have carried family furniture with them (see Appendix B).

The chest of drawers in Fig. 62 has inlay on the drawer fronts that includes stringing and four quarter fans per drawer. The canted, lamb’s tongue stiles have floating vine inlay above and below what could be either an abstract pinwheel or quatrefoil (Fig. 63). Barber pole rope is situated at the bottom of each stile, as if it is climbing the side of the chest. The second chest (Fig. 64) mirrors the other’s two-over-three graduated drawer arrangement. The chests of drawers also share stringing and four quarter fans per drawer front; however, unlike the first example, the paint remnants on the second chest are incredibly vibrant. Its canted, lamb’s tongue stiles feature abstract inlaid vines growing from the base of the stile. Above the vines, scribed fish face upwards on the stiles as if “swimming” upstream (Figs. 65 and 66).

The inclusion of inlaid piscine and botanical devices is a particularly imaginative interpretation of an agrarian region so dependent on waterways such as Big Limestone Creek and other tributaries of the Nolichucky River. The two chests of drawers exemplify the cultural palette of the rope and tassel school furniture. Like the gamecock corner cupboards, the chests indicate that rope and tassel cabinetmakers associated selected motifs per their own—or their patrons’—aesthetic and imagination.

As the nineteenth century progressed, furniture displaying the rope and tassel school’s palette of symbols and designs increasingly moved south and west of the Nolichucky River Valley. Some of these inlaid heirs to the rope and trassel tradition have connections to East Tennessee craftsmen and owners through a myriad of tangled relationships.

An example of a rope and tassel corner cupboard (Figure 67) is on display at the East Tennessee History Center.[118] This cupboard features an open ogee arched pediment with a central finial. The eight-light arched upper doors are framed by a barber pole pattern rope that descends from a right angle to the second light terminating with a tassel (Figure 68). Compass stars situated at the corners of the rope are the only other inlay decoration on the cupboard.

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation acquired a diminutive rope and tassel chest of drawers (Figures 69 and 70). This is the only known small-scale example in the group and was inspired by the rope and tassel tradition but probably created later and elsewhere. The chest dates to the 1830s, a decade or two later than the core assemblage of East Tennessee’s rope and tassel furniture, and it has a twentieth-century recovery history in South Carolina. Tara Gleason Chicirda, Colonial Williamsburg’s curator of furniture, states that the diminutive dimensions of the chest probably suggest it was a specific commission and “the inlay may have been a request of a patron who was familiar with the rope and tassel motif on the earlier cupboards.”[119]

Evidence of overcut marks and misalignments suggest the chest of drawer’s cabinetmaker was not as familiar with the scribing techniques employed by the McAdamses. Also diverging from the techniques used by the McAdamses and associated rope and tassel cabinetmakers in the Nolichucky River Valley, this chest’s barber-pole patterned rope is made of individual pieces. The barber pole pattern is continued as a banding just above the skirt as well. The tassel appears to be a single inlay piece scribed with vertical lines to suggest fringe (Fig. 70). There is no evidence of dyes on the inlay, although the chest was refinished at some point.

Another significant difference between this chest and the school’s primary examples from Tennessee is the wood; rather than cherry and/or walnut primary woods and poplar and/or yellow pine secondary woods, this diminutive chest is made of basswood. While basswood is often considered the exclusive material of furniture in northern states such as Vermont, dendrology suggests that basswood was also present in southern states and a native wood in Appalachian Tennessee.[120] Thus this small chest could well have been made in East Tennessee.

Interpretations of the rope and tassel also appear in the Deep South. The Classical Institute of the South documented a corner cupboard (Figure 71) with provenance and chronology that eliminate it from the primary Nolichucky River Valley rope and tassel group.[121] The corner cupboard was made for Thomas McCrary (1789–1865) of Huntsville, Alabama and remained in his family for four generations.[122] The piece is of note to this study, however, because it boasts clear design inspirations from East Tennessee: Its cabinetmaker married the inlaid medallions found on the French of feet of Thomas Kinnard’s desk (see Fig. 13) with draped cords and vines that descend from the cornice as tassels (Figure 72).

As a final example, an early-nineteenth-century corner cupboard at the Tennessee State Museum (Figure 73) exemplifies how the rope and tassel tradition remained popular throughout to the Craftsman revival of the early twentieth century. The cupboard features a square-pattern rope and tassels (Figure 74) that appear to be original to the cupboard’s early nineteenth century production; however, the pateraes and mass-produced inlay pieces on the recessed-panel lower doors (Figures 75 and 76) were added later.[123] Michael W. Bell, the Tennesee State Museum’s curator of furniture, also found evidence of electric power tool marks, up to three types of replacement secondary woods, and lower doors that do not match the casework.[124] A twentieth-century woodworker exerted great effort to repair and enhance an old and probably abused rope and tassel cupboard in hopes of increasing its worth. As such, this cupboard reveals a continued desire for collectors to acquire corner cupboards for storage and display as well as the enduring attraction and legacy of the rope and tassel tradition.

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

Scholars sometimes underestimate Backcountry arts and artisans by focusing on the limitations of cabinetmakers, but the shop of Hugh McAdams and others highlight an efficient and imaginative craft tradition. The rope and tassel school’s cultural palette reveals the imagery and symbolism of the backcountry that regional stereotypes have long overshadowed. The tradition is one of many examples of Backcountry entrepreneurship that formed a more permanent landscape in the early American Republic.

The rope and tassel motif of East Tennessee’s Nolichucky River Valley matters because it reflects a particular time and place in America. Patriotism, slavery, agriculture, geography, and religion all played a role in the changing discourse of material life in the first decades of Tennessee statehood. An integral part of a community that sought to put down roots, the rope and tassel cabinetmakers created large examples of case furniture that denoted cultural norms and class. That is, until the next generation looked westward. The cultural palette generated by the McAdamses and their colleagues and competitors spoke to the social and material aspirations of Nolichucky River Valley residents as expressed through Republican and agrarian symbolism.

Amber Clawson is director of the Historical Association of Catawba County. This article is based on her doctoral dissertation at Middle Tennesse State University, titled “Building Tennessee: The McAdams Family Trade and Identity in the Southwest Backcountry.” She can be reached at [email protected].

Appendix A: Transcribed Estate Sale of Hugh McAdams[125]

|

Bidder |

Item |

Price |

Page |

|

Isabella McAdams |

3 beds bedsteads & furniture |

$10.00 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 cupboard and furniture |

$5.00 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

2 pots 1 oven & lid 1 kettle & spade |

$5.00 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 bureau |

$5.00 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

2 small wheels 1 large ditto 1 reel |

$5.00 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

2 pair fire irons |

$1.60 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

10 crocks |

$1.34 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 pair dog irons |

$1.01 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 cullinary (sic)1 coffee pot 1 straner (sic) 1 tin cap |

$1.00 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 coffee mill |

$1.00 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 table |

$1.00 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

10 chairs |

$1.00 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

9 books & box |

$1.00 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

2 bedsteads |

$1.00 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 table |

$1.00 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 rolling pin |

$0.60 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 grid iron |

$0.54 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

2 pot racks |

$0.51 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 flat iron |

$0.35 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 churn |

$0.25 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 knife box 16 knives & forks |

$0.25 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 bread tray & meal tub |

$0.25 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

flesh fork & ladle |

$0.25 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 umbrella |

$0.25 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 sive (sic) |

$0.10 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

2 pitchers |

$0.10 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1/2 gallon & 2 funnels |

$0.10 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 pail |

$0.10 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 half bushell & bucket |

$0.10 |

328 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

3 baskets |

$0.10 |

328 |

|

Archa Frame |

1 big wheel |

$2.40 |

329 |

|

Elijaha Cahell |

1 book |

$0.50 |

329 |

|

Elisha Cahill |

1 rifle gunn (sic) |

$16.50 |

329 |

|

George White |

1 saddle |

$11.51 |

329 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 plow & irons 2 clevises & double trees |

$3.01 |

329 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 ax |

$0.51 |

329 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 pile plank |

$0.27 |

329 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 shovel plow & irons |

$0.25 |

329 |

|

James Bacon |

1 waggon (sic) & back bands |

$110.00 |

329 |

|

James Nelson |

1 slave named Moses |

$54.00 |

329 |

|

James Nelson |

1 slave named Sarah |

$15.00 |

329 |

|

James Robinson |

1 ax |

$2.12 |

329 |

|

John Ferguson |

1 crow bar |

$2.90 |

329 |

|

John Ferguson |

1 sledge |

$0.77 |

329 |

|

Samuel Bacon |

1 log chain |

$4.50 |

329 |

|

Samuel Bacon |

1 ax |

$1.25 |

329 |

|

Samuel Bacon |

1 shovel plow |

$0.57 |

329 |

|

Samuel Bruin |

1 pile plank |

$0.55 |

329 |

|

Samuel Bruin |

1 pile plank |

$0.28 |

329 |

|

Samuel Lane |

1 cupboard |

$21.00 |

329 |

|

William Carmicle |

1 side board |

$31.00 |

329 |

|

William Guinn |

1 pile plank |

$5.00 |

329 |

|

William Guinn |

1 book on architecture |

$4.26 |

329 |

|

William Guinn |

1 pile plank |

$3.01 |

329 |

|

William Guinn |

1 pile plank |

$2.35 |

329 |

|

William Guinn |

1 pile plank |

$2.00 |

329 |

|

William Guinn |

1 pile plank |

$2.00 |

329 |

|

William Guinn |

1 pile plank |

$1.85 |

329 |

|

William Guinn |

plank on negroe house loft |

$1.13 |

329 |

|

William Guinn |

1 pile plank |

$0.68 |

329 |

|

Zacha Hale |

1 big wheel |

$0.76 |

329 |

|

Abraham Britten |

1 curry comb |

$0.40 |

330 |

|

George Smith |

1 sorrel mare |

$20.52 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 cow |

$6.26 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

loom & tacklen |

$5.00 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 cutting box & knife |

$2.01 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

some pieces of cast iron |

$1.80 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 side saddle |

$1.03 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 saddle |

$1.03 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

Table clothes |

$1.01 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 pair horse geers |

$1.01 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 hackle 3 pairs shears candlestick snuffers |

$1.00 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 bell & strap |

$0.52 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

tallow |

$0.51 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 meat vessel |

$0.28 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 cyder barrel |

$0.25 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

soap & fat |

$0.25 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

pieces of cart iron |

$0.25 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

iron wedge & drawing knife |

$0.25 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

4 earthen vessels |

$0.10 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

tallow garter loom |

$0.10 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

cly (sic) tub |

$0.10 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

weavers spools |

$0.10 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 paving machine |

$0.10 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 pair saddle bags |

$0.10 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

3 bags |

$0.10 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 box |

$0.05 |

330 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 old riddle |

$0.01 |

330 |

|

John Ralston |

1 watch |

$8.50 |

330 |

|

Maybury Cox |

2 calves |

$3.61 |

330 |

|

Samuel Blair |

2 open barrels |

$1.62 |

330 |

|

Thomas Guinn |

1 cow |

$11.60 |

330 |

|

Wm B Adenale |

1 cow |

$10.00 |

330 |

|

Andrew Grayham |

2 sash planes |

$1.45 |

331 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 clock & case |

$30.25 |

331 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 bay mare |

$5.00 |

331 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

3 bushels flax seed |

$0.53 |

331 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 fire shovel |

$0.29 |

331 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 sickle |

$0.27 |

331 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

2 pitchers |

$0.26 |

331 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 open barrel |

$0.25 |

331 |

|

James Cunningham |

some small tools |

$0.32 |

331 |

|

James Duncan |

1 single barrel |

$0.50 |

331 |

|

James Duncan |

1 keg |

$0.50 |

331 |

|

James Duncan |

1 Jack plane |

$0.30 |

331 |

|

John Robston |

1 sickle |

$0.75 |

331 |

|

John Robston |

some small tools |

$0.15 |

331 |

|

John Robston |

3 squares |

$0.15 |

331 |

|

Nathan Shipley |

1 scythe & cradle |

$1.75 |

331 |

|

Nathan Shipley |

1 jack plane |

$0.25 |

331 |

|

Nathaniel Jones |

1 sickle |

$0.70 |

331 |

|

Robert McAdams |

375 feet inch plank |

$3.61 |

331 |

|

Robert McAdams |

1 oven & lid |

$3.01 |

331 |

|

Robert McAdams |

clamps |

$2.00 |

331 |

|

Robert McAdams |

cabbage machine |

$1.51 |

331 |

|

Robert McAdams |

275.5 feet inch plank |

$1.50 |

331 |

|

Robert McAdams |

1 conk shell |

$1.31 |

331 |

|

Robert McAdams |

1 pair cart boxes |

$0.77 |

331 |

|

Robert McAdams |

1 pair upper leathers |

$0.64 |

331 |

|

Samuel Brien |

1 hand ax |

$1.26 |

331 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

some plank in cabin |

$1.93 |

331 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

1 turning lathe 2 gouges 1 chessell (sic) |

$1.15 |

331 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

1 grove 1 jack plane stock 1 plane B |

$1.03 |

331 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

1 stone hammer |

$0.53 |

331 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

1 square |

$0.16 |

331 |

|

Andrew Grayham |

2 planes |

$1.75 |

332 |

|

Andrew Grayham |

2 planes |

$1.50 |

332 |

|

Andrew Grayham |

some small tools |

$1.25 |

332 |

|

Andrew Grayham |

2 planes |

$1.14 |

332 |

|

Andrew Grayham |

2 planes |

$1.13 |

332 |

|

Andrew Grayham |

2 planes |

$1.01 |

332 |

|

Andrew Grayham |

1 plane |

$1.00 |

332 |

|

Andrew Grayham |

2 planes |

$0.81 |

332 |

|

Andrew Grayham |

1 plane |

$0.80 |

332 |

|

Andrew Grayham |

2 planes |

$0.70 |

332 |

|

Andrew Grayham |

2 planes |

$0.48 |

332 |

|

Enoch Keen |

4 planes |

$4.00 |

332 |

|

Nathan Nelson |

1 plane |

$1.15 |

332 |

|

Nathan Nelson |

2 planes |

$0.50 |

332 |

|

Nathaniel Jones |

1 saw |

$1.07 |

332 |

|

Nathaniel Jones |

1 plane |

$0.25 |

332 |

|

Robert McAdams |

1 vinearing (sic) saw |

$0.75 |

332 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

4 planes |

$4.62 |

332 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

2 planes |

$2.25 |

332 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

1 corner plane |

$1.51 |

332 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

small tools |

$1.31 |

332 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

1 corner plane |

$1.30 |

332 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

4 gouges |

$1.27 |

332 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

files |

$1.25 |

332 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

4 chissells |

$1.00 |

332 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

2 planes |

$0.66 |

332 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

some small tools |

$0.51 |

332 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

small tools |

$0.51 |

332 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

1 hammer |

$0.30 |

332 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

small tools |

$0.12 |

332 |

|

William Guinn |

small tools |

$1.36 |

332 |

|

Gregory Glasscoke |

1 claw hammer |

$0.38 |

333 |

|

Hugh Martin |

1 saw |

$0.95 |

333 |

|

James Duncan |

1 hand saw |

$3.01 |

333 |

|

James Duncan |

3 boxes containing small articles |

$0.51 |

333 |

|

John Robston |

1 hand saw file |

$0.15 |

333 |

|

John Robston |

marking tools |

$0.15 |

333 |

|

John Stephenson |

1 mallet |

$0.07 |

333 |

|

Nathan Nelson |

1 work bench |

$1.25 |

333 |

|

Robert McAdams |

1 sash saw |

$3.00 |

333 |

|

Robert McAdams |

1 tenon saw |

$2.87 |

333 |

|

Robert McAdams |

1 tenon saw |

$2.87 |

333 |

|

Robert McAdams |

1 dovetail saw |

$2.32 |

333 |

|

Robert McAdams |

1 profile machine |

$0.02 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

1 hand saw |

$3.80 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

7 files |

$2.25 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

2 small boxes & contents |

$2.02 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

5 locks |

$2.00 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

1 work bench |

$1.79 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

glue pot |

$1.43 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

2 boxes with their contents |

$1.30 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

1 whetstone |

$0.75 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

small articles |

$0.71 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

3 boxes with their contents |

$0.55 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

1 saw set |

$0.41 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

3 gimblets |

$0.31 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

patterns |

$0.19 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

2 mallet |

$0.13 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

1 gimblet |

$0.12 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

boxes & pieces of wood |

$0.12 |

333 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

1 whetstone |

$0.07 |

333 |

|

William Guinn |

1 plane |

$1.25 |

333 |

|

Wm B Odenale |

1 shaving horse & grindstone |

$1.02 |

333 |

|

Abednego Hale |

3 sheep |

$4.15 |

334 |

|

Gregory Glasscoke |

1 razor & box |

$0.25 |

334 |

|

Isaac Horton |

3 sheep |

$5.00 |

334 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

remainder |

N/A |

334 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 watch |

$30.00 |

334 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

9 sheep |

$11.01 |

334 |

|

Isabella McAdams |

1 kettle washing machine & tub |

$2.00 |

334 |

|

John Robston |

1 key for watch |

$0.52 |

334 |

|

Robert McAdams |

1 rule |

$0.50 |

334 |

|

Samuel Bruen |

1 rule |

$0.41 |

334 |

|

Uriah Hunt Jr |

3 sheep |

$3.25 |

334 |

Appendix B: McAdams Family Tree

McAdamses identified as cabinetmakers are shown in blue boxes

[1] Philip Zimmerman, “Early American Furniture Makers’ Marks,” American Furniture, 2007, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2007), 133.

[2] For example, the chest of drawers in Fig. 64 has a Missouri recovery history (author’s conversation with Anne S. McPherson, Nashville, Tennessee, 4 November 2014). McAdams descendents migrated to Missouri, Illinois, Iowa and as far west as Nebraska (see Appendix B).

[3] Made in Tennessee: An Exhibition of Early Arts and Crafts (Nashville: Tennessee Fine Arts Center at Cheekwood, 1971).

[4] Ellen Beasley, “Tennessee Furniture and its Makers,” Antiques in Tennessee, reprinted from The Magazine ANTIQUES (New York: Straight Enterprises, 1971).

[5] Derita Coleman Williams and Nathan Harsh, C. Tracey Parks, ed., The Art and Mystery of Tennessee Furniture and Its Makers Through 1850 (Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society and Tennessee State Museum, 1988).

[6] Namuni Hale Young, Art & Furniture of East Tennessee: The Inaugural Exhibit of the Museum of East Tennessee History (Knoxville: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1997).

[7] Cultural ties united these two mountain communities and influenced the regions’ nineteenth-century craft and art.

[8] Betsy K. White, Great Road Style: The Decorative Arts Legacy of Southwest Virginia and Northeast Tennessee (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 2006). The database, titled the Betsy K. White Cultural Heritage Project, includes over two hundred documented objects made in Southwest Virginia and Northwest Tennessee before 1940. The database’s records are held at the William King Museum of Art in Abingdon, Virginia.

[9] Betsy K. White, Backcountry Makers: An Artisan History of Southwest Virginia and Northeast Tennessee (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 2013).

[10] Amber M. Clawson, “Building Tennessee: The McAdams Family Trade and Identity in the Southwest Backcountry” (Ph.D. dissertation, Middle Tennessee State University, 2015). I first presented the Hugh McAdams attribution in my 2012 MESDA Summer Institute final paper as well as in my lecture at the 2013 Colonial Williamsburg Antiques Forum.

[11] Anne McPherson included the McAdamses attribution in the first of her two articles for Antiques & Fine Art in 2015. Her articles present an excellent analysis of inlaid furniture made in Tennessee’s Washington and Greene counties, including examples outside the rope and tassel tradition. Anne S. McPherson, “Fans, Fish, And Tassels: Idiosyncratic Inlaid Furniture of Northeastern Tennessee,” Antiques & Fine Art (2015 Anniversary Issue); available online: https://www.incollect.com/articles/fans-fish-and-tassels-idiosyncratic-inlaid-furniture-of-northeastern-tennessee) (accessed 11 February 2017) and Anne S. McPherson, “Fans, Tassels, And Bellflowers: Idiosyncratic Inlaid Furniture Of Northeastern Tennessee Part II,” Antiques & Fine Art (Winter 2015); available online: (https://www.incollect.com/articles/fans-tassels-and-bellflowers-idiosyncratic-inlaid-furniture-of-northeastern-tennessee-part-ii).

[12] “A list of the property of Hugh McAdams, Decd.,” Inventories of Estates 1779–1821, Vol. 00, pp. 328-334, Clerk’s Office, Washington County Courthouse, Jonesborough, TN; available online: “Tennessee Probate Court Books, 1795-1927,” images 178–181, FamilySearch https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S7WF-SK9Y-R9?cc=1909088&wc=M6Q7-KM9 : 22 May 2014 (accessed 10 February 2017).

[13] Derita Coleman Williams, one of the few furniture scholars to discuss specific East Tennessee cabinetmakers, differentiates between “rural” and “town” craftsmen based on location and materials. For instance, prominent cabinetmakers in Greeneville (the county seat of Greene County) used imported mahogany more often than their rural counterparts. Derita Coleman Williams, “Early Tennessee Furniture,” Southern Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 1 (Fall 1986), 86.

[14] Murray Family Papers, Accession File 180, Archives of Appalachia, East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, TN.

[15] A note on spelling: originally the town of Jonesborough, Tennessee, was spelled “Jonesboro.” The modern spelling of “Jonesborough” (which has been in use longer than the first) has been used throughout this article to avoid confusion.

[16] After losing her first husband, Hugh McAdams’s youngest daughter, Jane (1811–1871), married Rowland “Robb” Perry Murray (1805–died before 1870), son of Shadrack Murray (1756–1845). It is unclear exactly how Rowland and Shadrack are related to Ephraim Murray, the cupboard’s first owner, but both Shadrack and Ephraim were born in Baltimore and migrated to Washington County in the late eighteenth century. The two Murrays were likely related and almost certainly knew one another.

[17] Williams, Harsh, and Parks, The Art and Mystery of Tennessee Furniture…, 176.

[18] McAdams served with Elias Bowman in the militia company of Captain Joseph Duncan. Captain Duncan’s Company, “Washington County List of Taxables 1797-1798,” Washington County Tax Books (1778-1885), Washington County Courthouse, Jonesborough, TN.

[19] Thomas Brabson sued McAdams over the transaction, arguing that the said purchase had progressed beyond initial discussions and that Brabson paid McAdams for the land before McAdams died. Brabson was secure in his purchase until 1822 when he became aware that Hugh McAdams had not fully owned the land he sold. In fact, the title never transferred from the eldest McAdams brother, John, to Hugh. According to the courts, John McAdams sold 63.5 acres to his younger brother Hugh in 1813, but shortly thereafter, “departed to parts unknown before the execution of title.” “Brabson Land Certificate,” Deed Book 17, p. 321, 20 June 1822, Washington County Deeds, Washington County Courthouse, Jonesborough, TN and “Thomas Brabson vs. John McAdams and the heirs of Hugh McAdams by their Guardian Joseph Hail (sic) Senior (September Term, 1822),” Washington County Courthouse, Jonesborough, TN.

[20] It should be noted that cherry primary and yellow pine secondary woods are also found on rope and tassel school furniture.

[21] See MESDA Object Database File S-13033; available online: http://mesda.org/item/object/cupboard-corner/17782/ (accessed 10 February 2017) and MESDA Accession File 5660.2; available online: http://mesda.org/item/collections/corner-cupboard/20767/ (accessed 10 February 2017).

[22] “A list of the property of Hugh McAdams, Decd.,” 329 and 331.

[23] Ibid, 333.

[24] Most of the rope and tassel school furniture forms date between 1800 and 1825. Extending the search to mid century revealed important qualities of the cabinetmaking trade by decade but the earlier a cabinetmaker worked the higher the likelihood that he was involved in rope and tassel furniture production. The search of the MESDA Craftsman Database was generated on 15 August 2014 by Kim Wilson May, manager, MESDA Research Center, Winston-Salem, NC.

[25] For instance, carpenters Thomas Murphey and Samuel Bitner were farmers who, according to surviving documents, primarily produced coffins. Both owned basic carpentry and farm utensils and appear repeatedly in estate records for the repayment of coffin construction. Based on this evidence, it is unlikely that either man executed the detailed inlay of the rope and tassel school furniture.

[26] East-Tennessee Patriot (Jonesborough, TN), 30 November 1819, 4.

[27] Ibid.

[28] This desk was sold at Charlton Hall Auctions in Columbia, SC (10-11 April 2015, Lot 61).

[29] “A list of the property of Hugh McAdams, Decd.,” 328–334.

[30] See Tyler Blethen and Curtis Wood, eds., Ulster and North America Transatlantic Perspectives on the Scotch-Irish (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1997).

[31] The McAdams family in this study should not be confused with the McAdams enclave in eastern North Carolina. Their genealogy and community ties are documented at length in I. D. Craig, A Historical Sketch of New Hope Church, in Orange County, NC (Reidsville, NC: New Hope Church, 1891).

[32] The migration timeline of the three McAdams men is unclear due to the lost and contested deeds in the region during the last decade of the eighteenth century. Thomas McAdams’s first deed does not survive but his land along Big Limestone Creek is referenced posthumously in a Robert McAdams deed. See “Deed Samuel Davies to Robert McAdams, Washington County Tennessee Land Records Deeds, 15-154 (1813), Washington County Courthouse, Jonesborough, TN.

[33] David R. Starbuck, “The Archaeology of Rural Industry,” in Unlocking the Past: Celebrating Historical Archaeology in North America, edited by Lu Ann De Cunzo and John Jameson (Gainesville: University of Florida, 2005), 146.

[34] Jen Stoecker, C. Van West, and Middle Tennessee State University Center for Historic Preservation, “The Transformation of the Nolichucky River Valley, 1776-1960” (Washington, DC: National Register of Historic Places, 2001), section E, p. 15.

[35] Captain Duncan’s Company, “Washington County List of Taxables 1797-1798.”

[36] Ibid.

[37] “McAdams Marriage License,” Tennessee State Marriages, 1780–2002, 9 June 1800, p. 108, Greene County, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, TN; available online: http://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=1169 (accessed 10 February 2017).

[38] “Thomas McAdams Will, 3 Dec. 1811,” Washington County Tennessee Will Book, Vol. 1, 1779–1858, 3 December 1811, pp. 94-95, Washington County Courthouse, Jonesborough, TN; available online: https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-2R1B-Z9?i=63&wc=M6QW-LMS%3A179850501%2C180221401&cc=1909088 (accessed 10 February 2017).

[39] Ibid.

[40] “Deed of Indenture,” Deed Book 8, pp. 52-54, 6 November 1803, Washington County Deeds, Washington County Courthouse, Jonesborough, TN.

[41] “McAdams Marriage License,” Tennessee State Marriages, 1780–2002, 27 June 1799, p. 108, Washington County, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, TN; available online: http://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=1169 (accessed 10 February 2017).

[42] “A list of the property of Hugh McAdams, Decd.,” 329–334.

[43] Alternatively, a “profile machine” may have been a tool to make molding profiles or other elements more closely related to cabinetmaking. “A list of the property of Hugh McAdams, Decd.,” 333.