Sometime early in his teens George Ladd (1802–1864) demonstrated an ability to paint likenesses of people. Leaving behind his first work experiences as a seaman, Ladd became an itinerant portrait artist. Advertising his services for painting and repairing portraits as well as ornamental painting, he traveled from New England to southern centers of commerce such as Richmond, Virginia; Charleston, South Carolina; New Bern, North Carolina; and Macon, Georgia. There are ten portraits by him known to survive, two miniatures and eight waist-length portraits. The paintings span a period of forty-five years from 1815 to 1860. This article reveals Ladd’s work as that of a competent artist, although as far as we know he was untrained. George Ladd’s paintings show that he was familiar with popular techniques of portraiture, perhaps educating himself by reading and observing the work of successful artists of his time. Eventually he settled permanently with his wife and family in Winnsboro, Fairfield County, South Carolina, where by word of mouth and reputation within the community he obtained commissions for portraits. In fact, the sitters in George Ladd’s known paintings from the 1840s onward are all from Fairfield County.

George Williamson Livermore Ladd was born in Plymouth, New Hampshire in 1802, the oldest of four sons of Daniel Ladd and Lydia Dow. His mother died when he was nine years old. Some of the New England Ladds participated in the merchant shipping trade while others were writers, printers, and artists. Daniel Ladd’s siblings lived in Haverhill and Salem, New Hampshire; Boston, Massachusetts; and northern New York.[1] There is little primary evidence that illuminates George Ladd’s early life, except one: In 1818 at the port of Savannah, Georgia, fifteen-year-old George Ladd was described in a document for the protection of seamen.[2] That record reveals that George Ladd “has a dark complexion, dark eyes, dark hair, and [illegible] nose,” stood five feet, five inches, and was a citizen of the United States.[3] “Plymouth, New Hampshire” and “Boston” were handwritten at the bottom of the document.

Although the particulars are unknown, Ladd must have received an education in his youth that would prove itself in his adult life as a teacher and in academic and mercantile operations. Whether or not his education included drawing or painting is unknown, but there are unsubstantiated family stories that George Ladd studied under noted artist Samuel F. B. Morse. Also a New Englander, Samuel F. B. Morse (1791–1872) began painting after graduation from Yale in 1810. He studied in London from 1811 to 1815 under Washington Alston and Benjamin West. After returning to America and establishing a painting room in Boston from 1815 to 1816 to exhibit his London work, Morse apprenticed fourteen-year-old Henry Cheever Pratt (1803–1880) of New Hampshire in 1817 to study under his tutelage and assist him.[4] [5] The year before, in 1816, Morse worked as an itinerant artist in Concord and Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Did Ladd study painting as a young teenager under Morse in one of the New Hampshire locations? George Ladd and Morse may have crossed paths during the time when Morse discovered his future apprentice H.C. Pratt in rural New Hampshire.[6]

A thorough reading and study of Samuel F. B. Morse’s journals, letters, and biographies fail to corroborate family tradition that Ladd studied under Morse. An 1851 letter does provide some evidence that Ladd had lived in Boston, possibly when Morse had his gallery there and apprenticed Pratt. George’s brother, William H. Ladd, who lived and worked in Boston, corresponded with his brother and urged him to seek business there, and therefore see his friends and family in Boston.[7] The letter confirmed several important facts: George kept in touch with his family; his brother urged George to inquire about job prospects in Boston; and George previously lived in Boston and had family and friends there. As his brother William expressed, some of George’s friends, like George W. Crockett, achieved wealth, and such contacts were essential to conducting business in the nineteenth century.

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

Carolyn J. Weekley, emeritus curator of paintings at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, wrote “artists who provided paintings for early southerners, especially those artists who lived in or visited the South, did not work in isolation.”[8] Weekley further stated that beginning in the eighteenth century southern culture fostered a word-of-mouth system of connectivity between artists, sitters, and family that was more effective than advertising in obtaining commissions for portraits. George Ladd must be classified as a bird of passage, a non-southerner who established residences and found professional success in the South. Following the trends noted by Weekley, Ladd advertised in locations that were frequented by more established artists, where he could easily have observed and visited those artists who set up studios and displayed their works. He may have even taught himself or furthered his artistic technique by observing those painters and their work.[9]

Richmond, Virginia was an important center for itinerant artists in the nineteenth century.[10] Established artists who set up residences in Richmond included Charles Bird King, Benjamin Latrobe, George Cooke, Philippe A. Peticolas, and James Warrell. In September of 1825, at the end of a two-year period, George Cooke stated that he had “painted one hundred thirty portraits, forty of which had been done in Richmond.”[11]

It is in Richmond that the lives of George Ladd and his future wife Catharine Stratton (1809–1899), a native of Richmond, likely intersected. The couple wed in 1827 and a brief statement about their marriage was made in Mary T. Tardy’s The Living Female Writers of the South (1872): In the entry for Mrs. Catharine Ladd, Tardy stated that she was “married when eighteen years old to Mr. Ladd, a portrait and miniature painter,” but told nothing about the circumstances.[12] Catharine’s widowed mother Ann Stratton lived with the couple throughout her life.[13]

The couple’s first known residence together was in Charleston, South Carolina in 1828. Like Richmond, the port city of Charleston was attractive to artists during the early decades of the century. The following advertisement made known their location as across from St. Andrew’s Hall:

Portrait and Miniature Painting.

Mr. Ladd, (from the North) most respectfully informs the Ladies and Gentlemen of this place, that he intends to remain here for a season, and would be happy to devote his professional services, to those who may want LIKENESSES, Old PAINTINGS cleaned and repaired equal to new.

Mrs. L. acquaints the Ladies, that she intends taking a SCHOOL, for teaching the art of Colouring and Painting Flowers, Fruit, &c. in a new method, called Poonak [sic] Painting, taught in six lessons.[14] She will also teach Painting on Velvet and Paper in the usual way, likewise Embroidery, Bead, Wax, Shell, Chrystal, Ebony Work, &c.[15]

Specimens can be seen, and terms made known by applying at No. 101 Broad-street, opposite St. Andrew’s Hall.[16]

George Ladd offered diverse services that increased his opportunities for employment. He had some specimens for display in order for patrons to evaluate his ability, so he must have had enough experience to retain samples of his work. It was a brief stay of less than a year.[17] The Charleston market presented stiff competition for a beginner. Even the talented and well-known painter Samuel F. B. Morse confessed in a letter to his wife Lucretia that his work in Charleston dried up by January 1821.[18]

After their Charleston stay, George Ladd advertised in New Bern and Fayetteville, North Carolina, where William Joseph Williams painted and taught at the New Bern Academy from 1817 until his death in 1823. Ladd placed a newspaper advertisement in New Bern as follows:

Portrait and Miniature Painting.

Mr. Ladd (Late of Boston) Most respectfully informs the Ladies and Gentlemen of this place, that he intends to remain here a short time, and would be happy to devote his professional services to those who may want Likenesses. Mr. L. flatters himself, from his successful experience, he shall be enable [sic] to give satisfaction, to such as may favour him with their patronage. Specimens of his art, can be seen at Capt. Anthony’s, South Front-street. His terms are reasonable.[19]

In March 1830 Ladd submitted a short advertisement to the Fayetteville, North Carolina newspaper, “Mr. LADD. PORTRAIT, MINIATURE AND ORNAMENTAL PAINTER. Specimens can be seen at his house on Bow street.”[20] In April 1830 his advertisement read:

PORTRAIT, MINIATURE AND ORNAMENTAL PAINTING.

Mr. Ladd, formerly from Boston, most respectfully Informs the Ladies and Gentlemen of this place, that he intends to reside here for a season, and would be happy to devote his professional services to those who may want correct Likenesses. Old paintings cleaned and varnished, equal to new. His terms are reasonable. Specimens can be seen at his residence on Bow street and at Mr. J. Campbell’s Jewelry store.”[21]

The addition of ornamental painting to his list of artistic skills expanded George’s chances of commissions. Signs, for example, could be included in the specimens of those projects displayed at Mr. Campbell’s Jewelry store in Fayetteville.[22]

George Ladd was head of household in the 1830 United States Federal census in Fayetteville. In addition to Catharine and her mother there was a male child under the age of five. In the same year George registered as head of household in Ricks, Nash County, North Carolina; there were no other entries of persons in that household.[23] Nash County is northeast of Raleigh. If George Ladd found patrons for portraiture in New Bern, Fayetteville, or Nash County, North Carolina, those paintings remain unknown. A disastrous fire devastated the town of Fayetteville in 1831, leaving few buildings.[24]

During the next five years Catharine Ladd’s advertisements for female academies were the only public notices of their location. Catharine Ladd was principal of Rolesville Female Academy near Raleigh, North Carolina, in January 1833 and continued through that year. Her advertisement listed the English course of study along with ornamental subjects in painting, drawing, embroidery, and music. “Drawing and Painting-on paper, silk, satin and velvet-India painting, Embroidery, Lace work, Bead work, Wax work, Ebony work, Fillagree work, Bronzing and Gilding including the above, 12 per session.“[25]

It is undocumented if George lived in Rolesville while Catharine conducted Rolesville Female Academy in 1833 and 1834, however, George Ladd’s talents were relevant in teaching art as well as in skills for other ornamental subjects in female academies like filigree work, bronzing, and gilding.[26] In Fayetteville his advertisement stated that paintings were displayed at his residence and also at “Mr. J. Campbell’s Jewelry store,” but if there were an association with a jeweler is not clear. Engraving was part of a jeweler’s craft.[27] Engraving and gilding as well as the aforementioned decorative painting were all part of the itinerant artists’ expertise.

Ads for Catharine Ladd’s academic endeavors were not found from 1834 to 1837, but that fact does not discount her teaching during those years.[28] During the mid-1830s Catharine published poetry in the Southern Literary Messenger, an occupation that yielded income as an author. The Ladds’s financial situation may have been compromised for a family of three adults and one child. Itinerant portrait artists at the time could expect as little as one dollar and fifty cents for a portrait to twenty dollars for a pair of portraits of siblings or spouses; some even exchanged a portrait for room and board.[29] Samuel F. B. Morse was in Concord, New Hampshire in 1816 having success by painting five portraits at fifteen dollars each.[30]

The birth of a son, Albert Washington Ladd, on 15 October 1836 confirmed the Ladds’s presence in Chester County, South Carolina.[31] By 1838 Catharine accepted teaching duties at a female academy in Macon, Georgia. George’s advertisement for painting did not appear there until 1839, although their second son, Charles Henry, was born in Macon on 1 April 1838.[32] Along with advertising his services was a testimony by several citizens (unsigned) about his qualifications in May 1839:

On Sunday we visited Mr. Ladd’s room for the purpose of seeing some of his late specimens of Paintings. There were several Portraits which we recognized at first glance, to be of those of some of our citizens; which were done in a style that reflects credit on the Artist. It is hoped that Mr. L. will make this city his permanent residence; and as for sufficient encouragement to induce him to do so, it is only necessary to examine his Paintings. In short, all who wish to preserve the features of near and dear friends, when the body is slumbering with those that are no more, we say, call at Mr. L.’s room on Cotton Avenue.[33]

According to this statement George Ladd painted portraits of some citizens in Macon, but he was not a permanent resident. Three months later the Ladds moved to Brattonsville in York County, South Carolina, located on the border with North Carolina, where Catharine established a school on the plantation of the Dr. John Bratton family. They remained until January 1842. There are no known surviving portraits by George Ladd from 1836 to 1842. It was their next move, two counties to the south, to Fairfield County, thirty miles north of the state capital Columbia, where both of their careers flourished and where the Ladds lived out the rest of their lives (Figures 1 and 2).

The Woodwards persuaded Catharine to operate a female academy in Winnsboro. An advertisement verified her presence there in 1843.[34] After the 1844 session at Winnsboro Female Seminary, the Ladds left Winnsboro but remained in Fairfield County.[35] She accepted a position from John Feaster at the newly built Feasterville Female Seminary, located twenty miles northwest of Winnsboro, where they remained through 1848. The following year the Ladds returned to Winnsboro where Catharine began Winnsboro Female Seminary.[36] They remained proprietors and teachers of that business until the Civil War.

Portraits by George Ladd

Portraits in Miniature

The earliest documentation of George Ladd as an artist is a portrait in miniature (Figure 3) of Peter Townsend (1770–1857), the son of Peter and Hannah Townsend, New York iron manufacturers. The New York Historical Society owns the painting, dated circa 1815, corresponding to the sitter’s age and attire. Townsend is depicted wearing a War of 1812-era civilian coat with a raised collar, jutting out severely. On the lower collar are several gold buttons. His face is framed by a shirt collar raised to his ears and his brown hair, neatly groomed. His nose, mouth and chin features add dimension to a full face. The portrait is watercolor on ivory and inscribed on the reverse: “Geo. W. L. Ladd/Portrait in Miniature/Painter.”[37] The miniature is in a deep oval, black wooden frame, gilded with gold trim on the inner and middle raised ovals.

For the circa 1815 date to be correct, George Ladd would have been about thirteen years of age when Townsend’s miniature was painted, several years before he began painting professionally. Upon examining an image of the Townsend painting, however, the noted portrait miniature authority Elle Shushan suggested it could be a copy.[38] If that were so, then Ladd’s miniature portrait of Townsend was most likely completed later than 1815, after Ladd had left his life as a seaman and became an itinerant artist.

In 1835 George Ladd made another portrait in miniature, this one of Midshipman Matthew Maury (Figures 4 through 7) painted in Fredericksburg or Richmond, Virginia. How George Ladd came to paint Matthew Fontaine Maury (1806–1873), a pioneering oceanographer and navigator known as the “Pathfinder of the Seas,” is unknown; however, the portrait is signed, identifying the artist as George Ladd. The portrait is painted in oil on ivory in a small gold, oval case. On the back of the locket in the center oval were engraved the initials “MFM.”[39] Inside the frame is an oval piece of backing paper with an inscription printed in pencil, “G.W. Ladd pinxt.” Behind the paper is enclosed a lock of hair resting against a gold-plate backing. Other miniature portraits of Matthew Maury exist but Ladd’s is considered to be an original, not a copy.[40]

Dressed in his navy blue uniform, Midshipman Maury is painted with the details of military rank on his coat with brass buttons and an anchor embroidered on his coat lapel.[41] His white vest, open in the front, reveals a small pin on his black cravat, perhaps a stickpin of military significance. Matthew Maury is turned slightly to his left with his eyes glancing left. His facial hair beneath his nose and the beard covering his chin and jaws are neatly trimmed.

Waist-Length Portraits

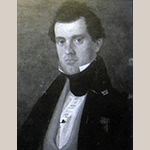

As previously mentioned, the birth of their son in 1836 recorded the Ladds’s presence in Chester, South Carolina, where William Alexander Rosborough (1811–1869) was a planter. His bust-length, oil-on-canvas portrait dated 1835 is signed “Ladd pinxt.” (Figure 8).[42] George Ladd added some details in the clothing of Rosborough such as small adornments on his raised coat collar. The white linen shirt with tucks at the front is not smoothed out under the vest, but is bloused out. The buttons appear to be mother-of-pearl, edged in gold. Tied around his neck is a high, black silk neckerchief above which can be seen the shirt collar edges. His dark coat contrasts to the lighter color of the worsted vest, the folded collar of which extends along a V-neck.

While a bust-length portrait, the painting does not show Rosborough’s hands, which were a more difficult part of the body to portray.[43] At twenty-five years of age, Rosborough’s short, full head of hair is casually combed, allowing the natural texture to show. The softened, slightly out-of-focus overall features, popularized by the painter Thomas Sully, also required less work for the artist to render details. This portrait achieves the artist’s goal of revealing the unique character of his sitter in a simple way and reflects the technique of itinerant, self-taught artists of the mid-nineteenth century.

Woodward Family, 1840s, Fairfield County

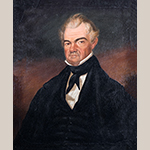

The Osmund Woodwards of Fairfield County sent their daughters to Brattonsville Female Seminary. Through their persuasion Catharine Ladd left Brattonsville and initially taught at Winnsboro Female Seminary in 1843 and 1844. The Hon. Osmund Woodward (1795–1863) was a planter who built the First Baptist Church in Winnsboro and was a Representative to the South Carolina Legislature from Fairfield County, from 1842 to 1844.

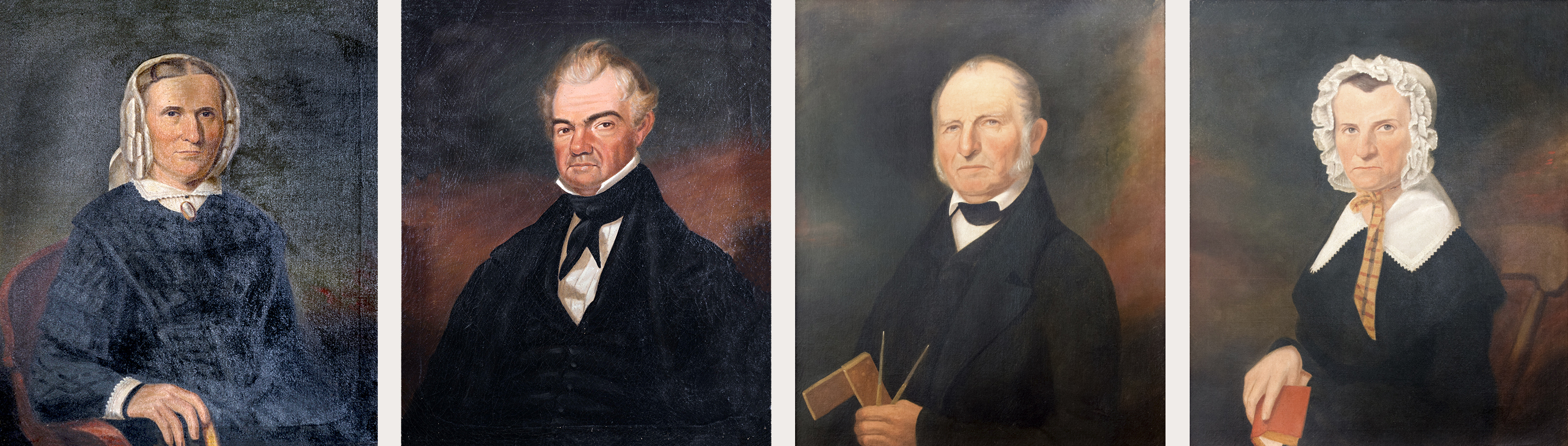

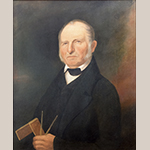

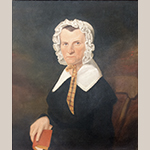

George Ladd painted waist-length portraits of Osmund Woodward and his wife Martha Alice Wyche Williamson Woodward (1796–1880) in oil on canvas. These husband and wife portraits date to the 1840s (Figures 9 and 10). Woodward is dressed in a fashionable black worsted coat and a silk vest with small covered buttons. At his throat a black silk cravat secures the raised collar of his white linen shirt with tucks at the front. His facial features have fullness achieved by lines of contour around his prominent nose, mouth, and definition in his cheekbone. As in the Rosborough portrait, George Ladd concentrated on his sitter’s face without showing his hands or depicting objects.

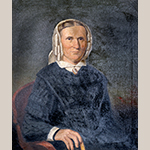

The painting of Mrs. Woodward includes more detail in the setting and her garments. She sits in a plain, red wooden chair against a dark background that changes hues to lighter tones at her shoulders. She is dressed in black silk satin or lustring (silk taffeta), reflecting a glossy sheen in the pattern, in the latest fashion with her shoulders sloping in the manner required by the dress style. A gold cameo is pinned at her neck and her right elbow rests on the chair arm with her hand extended, a closed book barely visible, grasped in her hand. Together, the portraits of the Woodwards reflect credible likenesses of a prominent Winnsboro family.

Feaster Family, 1842–1844

George Ladd began painting portraits of the Feaster family members soon after leaving Brattonsville. There are four known portraits of the Feasters painted by George Ladd between 1842 and 1844. John Feaster (1768–1848) commissioned his portrait (Figure 11) and one of his cousin and housekeeper Mary Meador (dates unknown) (Figure 12) in 1844 when he was seventy-six years old. In his waist-length, oil-on-canvas portrait Feaster’s torso is turned slightly left while looking forward, with two objects clasped in his left hand that signified importance in his life: the compass and square, universal Masonic emblems of virtue and wisdom of conduct. For this portrait, George Ladd incorporated a technique known as “portrait d’apparat,” in which the artist uses objects from the sitter’s everyday life in the painting.

When John Feaster’s wife Drusilla Mobley (b.1774) died in 1807, his cousin Mary Meador raised his children and kept house for him. Mary Meador’s oil-on-canvas portrait is the same size as John’s painting. She is posed properly with a straight posture seated in a wooden chair as she faced the artist, holding a small red book in her left hand. Her fingers hold a place in the small downturned book, the size and thickness of a Bible or testament. Viewers would recognize the sacred book as a symbol of piety, a womanly virtue, as in the Martha Woodward portrait (see fig. 10). Mary’s black dress has barely defined capped sleeves and a white linen collar with embroidered trim. The gathered rows of lacy, trimmed cap edges framing Mary’s face soften the overall appearance of severity.

John Christopher Columbus Feaster (1819–1899) and his wife Martha Ann Cason (1820–1907) were painted together in one portrait (Figure 13). This is the only known painting by George Ladd with two subjects on one canvas. John C. was a planter, the son of Andrew Feaster III (1793–1869), and grandson of John Feaster who built Feasterville Female Seminary. He married Martha Cason in 1842. Their portrait is signed “Ladd, pinx[t]” and dated 1842 to 1844. The large canvas shows both subjects standing in a three-quarter view. The sitters seem to rest their hands on the back of a chair or are clasping a book in their joined hands.[44] Here the painter’s method is stiff and awkward, but intended to demonstrate affection. With hands showing, Martha Ann displays one gold band on her left ring finger and various rings on three fingers of her right hand. She wears a bracelet, perhaps tortoise shell, on the left wrist and at her neck a cameo brooch. Martha’s cheeks and lips are lightly pink, but her face, neck, and hands are pale compared to her husband. Her dark hair is sectioned, parted, and pulled back in a severe manner only slightly softened by a curl against her face on both sides. Her plain black dress is a simple style with a linen shift showing at the neck, emphasizing the open work on her dress bodice. As was the case in the Woodward portraits (see fig. 9 and fig. 10), Ladd included more details and adornment in the female garments, reflecting the women’s social status. In contrast, her husband is painted with little detail in his clothing. He is the only male in Ladd’s waist-length portraits depicted with facial hair, in this case a stylish beard from ear to ear under the chin and on the neck. John Feaster and his wife were in their mid-twenties when Ladd painted their portraits. He depicted a successful grandson of an immigrant family who had accomplished a comfortable life.

Nathan Andrew Feaster (1820–1861) was a brother of John Christopher Columbus Feaster. The family resemblance to his brother is obvious in his portrait, dated 1844 and signed “Ladd, pinx[t]” (Figure 14). In this portrait George Ladd effectively used side lighting and shadow on Nathan’s face. An important paper, perhaps a deed or letter, is shown in Nathan’s raised left hand—the best execution of hand in Ladd’s ten portraits. On the little finger is a gold ring, the shape of a signet ring. Nathan’s brown hair is combed high on the top in a wave that descends to wound curls above his ears, and neck-length in the back. The inscription on the paper reads “Mr. N. A. Feaster, Columbia, S.C.” In 1850, at age twenty-nine, Nathan was a merchant in Columbia, South Carolina. In 1860 he lived with his third wife and children near Greenville, South Carolina as a farmer with real estate valued at fifteen thousand dollars.[45] His handsome face with full lips pursed is more refined than those found in Ladd’s other portraits, illustrating that the artist had gained more experience and his artistic skills had improved. Nathan Feaster died serving the Confederacy during the Civil War in the Battle of Sharpsburg. His body was not recovered.[46]

Andrew Jackson McConnell Jr., 1858-1860

The last known painting by George Ladd is that of Andrew Jackson McConnell Jr. (1838–1864). Although its current location and ownership is unknown, well into the twentieth century this portrait was displayed over the mantle at Clanmore (Figures 15), a stately home in the Feasterville community (Figure 16).[47] [48] The son of Andrew Jackson McConnell Sr. (1803–1855) and Elizabeth Dawkins (1798–1840), A. J. McConnell Jr. was a prosperous farmer whose plantation, Shelton, was also located Feasterville. The McConnell children attended the Feasterville male and female academy where Catharine Ladd was formerly principal of Feasterville Female Seminary. Andrew Jackson Jr. married Sallie Amanda Coleman (1840–1858) in 1857. During the Civil War he served as a lieutenant with the South Carolina Volunteers, losing his life at the Battle of the Crater, Petersburg, Virginia on 30 July 1864.[49] George Ladd’s portrait of A. J. McConnell Jr. dates between 1858 and 1860. Comparing the portrait’s size to the mantle at Clanmore (estimated to be about six feet in length), its dimensions were comparable to the largest of the Ladd paintings.[50]

Addendum: Further study suggests that this portrait may date several years earlier and in fact depict Andrew Jackson McConnell Sr., who died when he was 52 years old and more closely matches the man in the painting’s visual age. His son would have been only in his twenties when the painting was completed.

Conclusion

George W. L. Ladd died on 14 July 1864 at home in Winnsboro, South Carolina. A letter from son A.W. Ladd serving the Confederate army in Charleston, South Carolina, to his sister, Josie (Josephine) Ladd, in Florida, confirmed his father’s death “from infirmity.”[51] His grave is marked with a contemporary stone inscribed with the words “Artist-Portrait Painter-Teacher.”[52]

In his will George Ladd designated his wife Catharine as executor to dispose of and divide his estate among their six children when and how she saw fit. There was no record of any auction or sale of his estate, an indication that he did not have debts. A probate inventory of the George W. Ladd estate in 1864 included “a picture of a ship in a storm” that was appraised at ten dollars.[53] Tragically, all their household possessions were destroyed in an 1865 fire when Union troops burned the town of Winnsboro. The picture could have been a George Ladd maritime painting, but nothing of the kind with his signature or provenance is known to exist.

As an artist, Ladd typifies in many ways other itinerant portraitists in the antebellum American South. Most likely self-taught, he traveled early in his career to cities where he could observe and learn from established painters. Although his work shows merit and despite some success painting portraits later in life, he remained unrecognized outside the specific localities where he plied his trade. Based on the number of his surviving portraits he could not have supported a family through painting, and he was primarily employed as a teacher. Ladd is atypical in that he benefited from his wife’s success as a founder and principal of female academies. By combining their talents and working together George and Catherine Ladd were able to transcend the itinerant lifestyle of a portrait painter, nurture six children, and provide for them a stable and prosperous life in Piedmont South Carolina.

Patricia V. Veasey is an independent scholar who writes and lectures on women’s history, particularly female education of the antebellum South in the Carolina Piedmont. She can be contacted at [email protected].

[1] Herbert Warren Ladd, The Ladd Family (New Bedford, MA: printed for the author by Edmund Anthony & Sons, 1890).

[2] Seamen’s Protection Certificates were obtained by paying a collector whose job was to acquire proof of citizenship, collect a fee, and then issue a certificate. Ruth Priest Dixon, comp., Indexes to Seamen’s Protection Certificate Applications and Proofs Citizenship, Ports of New Orleans, La., New Haven, Ct., Bath, Maine and additional ports (Baltimore, MD: Clearfield, 1998).

[3] Protection document #226, United States of America, 17 December 1818, Savannah, GA. A copy of the original document was in the Catharine Ladd Scrapbook, Private Collection.

[4] Afterwards he is referred to as H. C. Pratt.

[5] George C. Groce and David H. Wallace, “Henry Cheever Pratt,” in The New York Historical Society’s Dictionary of Artists in America, 1564-1860 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1957), 115.

[6] Ibid. H. C. Pratt was born in Oxford, New Hampshire in 1803, making him a contemporary of George Ladd. By 1827 Pratt established his own studio in Boston. Intriguingly, George Ladd’s North Carolina advertisements in New Bern (1829) and Fayetteville (1830) stated that he had previously lived in Boston.

[7] William H. Ladd to George W. Ladd, “J_ [illegible] 16th 1851,” 2016.028, Fairfield County Historical Society Collection, Fairfield County Museum, Winnsboro, SC.

[8] Carolyn J. Weekley, “1735-1790: Painters, Paintings, & the American South,” The Magazine ANTIQUES, January/February 2013; available online: http://www.themagazineantiques.com/article/painters-and-paintings/ (accessed 12 December 2017).

[9] In their recent article on Thomas Coram, “Portrait of Brigadier General William Washington,” authors Christopher Bryant and Sumpter Priddy quote William Dunlap’s 1834 biographical comments on Englishman Thomas Coram as a self-taught engraver. Dunlap said that Coram, while untrained, taught himself the art of portraiture in Charleston by reading, observing and visiting local artists. Christopher Bryant and Sumpter Priddy, “Portrait of Brigadier General William Washington by Thomas Coram,” MESDA Journal, Vol. 37 (2016); online: https://www.mesdajournal.org/2016/portrait-brigadier-general-william-washington-thomas-coram/ (accessed 12 December 2017).

[10] Donald B. Kuspit, David S. Bundy, et al., Painting in the South, 1564-1980, exhibition catalog (Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 1983), 64.

[11] Ibid.

[12] The entry on Mrs. Catharine Ladd was dated 1869. Mrs. Tardy gave the birth date for Catharine Stratton as 1810, not the correct date of 1808. Catharine’s marriage to George Ladd at age eighteen would put the marriage date at 1826-1827. Entry for “Mrs. Catharine Ladd,” The Living Female Writers of the South, Mary T. Tardy, ed. (Philadelphia, PA: Claxton, Remsen and Haffelfinger, 1872), 489-490.

[13] Catharine is believed to be an only child, therefore her widowed mother, Mrs. Ann Stratton, lived with her daughter’s family, as was the custom at the time.

[14] Poonah painting was “painting on rice or other thin paper in imitation of oriental work, by the application of thick body-colour, with little or no shading, and without background.” W. Little; H. W. Fowler; J. Coulson; C. T. Onions; The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd rev. ed. (Oxford, UK: Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1956), 1544.

[15] Theorem painting was achieved by applying oil paint on velvet or silk through stencils of flowers or fruit. The designs are traditionally painted on velvet and the work is then framed or matted. The stencils are multiple overlays and designs are always three-dimensional, primitive and stylized in nature. The resulting design is bridgeless—there are no gaps in between the overlays. Subjects often included foods, scenes, and symbols that were popular in the artist’s area. Deborah Chotner, American Naive Paintings (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1992), 370-71; cited from entry for “Theorem Stencil,” Wikipedia; online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theorem_Stencil (accessed 12 December 2017).

[16] Charleston Courier (Charleston, SC), 15 December 1828.

[17] In the 1 March 1829 edition of the Charleston Courier the name “George Wm. Ladd” appeared in the on the dead letter list.

[18] Anna Wells Rutledge, entry for “Samuel F. B. Morse,” Artists in the Life of Charleston: Through Colony and State from Restoration to Reconstruction (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1949), 130.

[19] Newbern Spectator (New Bern, NC), 3 October 1829.

[20] Carolina Observer (Fayetteville, NC), 25 March 1830.

[21] Ibid, 1 April 1830.

[22] The “Mr. Campbell” who displayed Ladd painted signs at his store was the Scottish-born John Campbell, a silversmith and jeweler who apprenticed in Fayetteville and moved to Nashville, Tennessee in 1836. That same year, 1836, Campbell was part of a group of nine craftsmen that formed the “Association of the Watch-Makers, Silversmiths & Jewellers of Nashville.” The association established price guidelines for the manufacture and repair of clocks, watches, silver, and jewelry, all recorded in Campbell’s ledger book now at MESDA as part of the Thomas A. Gray Rare Book and Manuscript Collection (call number TAG.096.1).

[23] 1830 United States Federal Census.

[24] “History, 1791—Present and Looking Forward,” City of Fayetteville, NC website; online: http://fayettevillenc.gov/government/city-departments/fire-emergency-management/history (accessed 12 December 2017).

[25] The Star (Raleigh, NC), 23 December 1832.

[26] Filigree work was open work decoration made out of very fine threads and usually minute balls of silver or gold used in jewelry. The work was embroidered with silk thread wrapped in gold or silver. Bronzing and gilding were methods of applying a gold surface to an object or textile by rubbing or painting with a bronze or gold powder. John and Hugh Honor Fleming, Dictionary of the Decorative Arts (New York: Harper and Row, 1877), 292.

[27] The miniature case enclosing the Matthew F. Maury portrait has the initials “M.F.M.” engraved on the reverse.

[28] No Chester County, South Carolina, newspapers are listed for the years 1834-1837. John Hammond Moore, ed. South Carolina Newspapers (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1988), 73.

[29] Alan Burroughs, John Greenwood in America, 1745–1752 (Andover, MA: Addison Gallery of American Art, 1943); see also, “Portraiture in a Developing Nation,” Currier Museum of Art Online Curriculum, online: http://curriculum.currier.org/portraiture/the_context.html and http://curriculum.currier.org/portraiture/the_artists.html (accessed 12 December 2017).

[30] Edward Lind Morse, ed. Samuel F. B. Morse: His Letters and Journals (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), 201.

[31] For Albert Washington Ladd’s birth, see Elsie K. Eaves, comp., “The Family Records of James M. Eaves,” person page 463; online: http://eavesphotos.com/JME-o/p463.htm (accessed 12 December 2017). In the 1840 United States Federal Census, George W. Ladd was recorded as head of a household consisting of himself, two white male children (under the age of 5 years old), two white females (one between 20 and 30 years old and the other between 60 and 70 years old), and two enslaved females (one under the age of 10 years old and the other between 24 and 35 years of age).

[32] Ibid.

[33] Macon Georgia Telegraph (Macon, GA), 14 May 1839. No examples of George Ladd’s work in Macon are known.

[34] South Carolinian (Columbia, SC), 23 November 1843.

[35] Fitz Hugh McMaster, “History of Fairfield County South Carolina” (Columbia, SC: State Commercial Printing Company, 1946), 66–68.

[36] Fairfield County Deed Book A 1, pp. 104-105, 10 February 1849, town lots 19 and 20, Caleb Clark, Sr. to George W. Ladd, recorded 24 July 1849, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC.

[37] See the New-York Historical Society Museum & Library catalog entry for Acc. 1967.15; online: http://www.nyhistory.org/exhibit/peter-townsend-1770-1857 (accessed 12 December 2017).

[38] I would like to thank Elle Shushan for examining two images of George Ladd’s miniatures and offering her comments. We met at MESDA in October 2011 when she presented her lecture “Face Painting Well Performed: Portrait Miniatures in the American South.”

[39] Elle Shushan commented that the engraved gold frame was of Scottish origin.

[40] Jeanne Willoz-Egnor, Director of Collections Management, Curator of Scientific Instruments, The Mariners’ Museum, Newport News, VA.

[41] In 1836 Maury was made lieutenant in the United States Navy and published his Treatise on Navigation in Philadelphia. Maury’s location in Fredericksburg as well as his midshipman’s uniform depicted in the painting confirms the date of his portrait to be 1834–1835. He would be portrayed as a lieutenant if it were done in 1836. Coordinating those dates with George Ladd’s known locations also confirm the years 1834–1835 as being a possible itinerant period for Ladd, there being no contrary evidence of a definite residence. Catharine Ladd wrote poetry for a journal published in Richmond, Virginia at this time. Catharine Ladd and Matthew Maury were both authors who published in Richmond’s Southern Literary Messenger. Edgar Allen Poe reviewed Matthew Maury’s book in 1836 at the same time Catharine’s poems appeared in the literary magazine under Poe’s term as editor. Catharine Ladd had maternal relatives of the Collins and Dabney families who lived in Richmond and Lynchburg, Virginia with whom George could communicate. A surviving letter from the year 1866 written by Emma Dabney in Lynchburg, Virginia sent family news to her second cousin Albert W. Ladd, son of George and Catharine, in Winnsboro. The letter proved that the families remained in touch with each other through the years. Emma Dabney to Albert W. Ladd, 27 August 1866, 2016.030, Fairfield County Historical Society Collection, Fairfield County Museum, Winnsboro, SC.

[42] The study image was a black-and-white copy illustrated in Christie Zimmerman Fant, Margaret Belser Hollis, and Virginia G. Meynard, eds., South Carolina Portraits: A Collection of Portraits of South Carolinians and Portraits in South Carolina (Columbia: National Society of The Colonial Dames of America in The State of South Carolina, 1996), 329. The present location of the original is unknown.

[43] I would like to thank Dr. Will South, Chief Curator, Columbia Museum of Art, Columbia, SC, for an interview on 10 April 2015 about the Woodward portraits by itinerant artist George Ladd. Dr. South stated that artists of George Ladd’s period did not have the means by which to learn human forms. Interview by phone with Dr. Will South, Chief Curator, Columbia Museum of Art, Columbia, SC, 10 April 2015. To read a blog about the author’s visit to the Columbia Museum of Art to study the Woodward portraits, see https://www.columbiamuseum.org/cma_stories/writers-view-collections (accessed 12 December 2017).

[44] Darkened through age, the portrait was difficult to analyze. It could be, for example, that Mrs. Feaster’s left hand is resting on the back of a chair placed in front of the couple because of the awkward placement of her hand.

[45] 1860 United States Federal Census.

[46] Nathan Feaster’s death is listed in family genealogy as 1861, however the Battle of Antietam did not occur until 16–18 September 1862.

[47] The author saw the portrait of Andrew Jackson McConnell Jr. at Clanmore in the 1990s before the estate was settled. A descendant living in the home said that according to family history George Ladd painted the portrait. The current location and owner of the portrait are unknown.

[48] Clanmore was completed in 1845 by John C. C. Feaster and after the Civil War sold to Major Charles W. Faucette Sr. “Country Tour” in Our Heritage, a guidebook of Fairfield County homes, circa 1949, 28; see also “Clanmore,” South Carolina Picture Project, SCIWAY.net; online: https://www.sciway.net/sc-photos/fairfield-county/clanmore.html (accessed 12 December 2017).

[49] J.P. Coleman, The Robert Coleman Family: From Virginia to Texas, 1652–1965 (Ackerman, MS: James P. Coleman, 1965) 287, 335.

[50] “Clanmore, Home of the Faucette Family,” in Our Heritage, 28-29.

[51] Albert W. Ladd to Sister (Josephine N. Ladd), 24 July 1864, 2016.029, Fairfield County Historical Society Collection, Fairfield County Museum, Winnsboro, SC.

[52] Grave marker for George Williamson Livermore Ladd, First United Methodist Cemetery, Winnsboro, Fairfield Co., SC; online: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/55749373/george_williamson-livermore-ladd (accessed 12 December 2017).

[53] The total value of the Ladd estate recorded in the probate inventory was $3,852.35 with $3,000 of that amount being assigned to five enslaved persons. Fairfield County, South Carolina, Probate Court, Estate Papers, George Ladd, Box 22, Pkg 207, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC.

© 2018 Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts

![Fig. 13: Portrait of John Christopher Columbus Feaster (1819–1899) and his wife Martha Ann Cason (1820–1907) by George W. L. Ladd, 1842–1844. Signed: "Ladd, pinx[t]." Oil on canvas; HOA: 38-1/2", WOA: 32". Collection of the Fairfield County Museum, Winnsboro, SC.](https://www.mesdajournal.org/files/Veasey_Fig_013_Thumb.jpg)