On 29 July 1775, following the long-established traditions among the Society of Friends, a young Quaker cabinetmaker named Thomas Pierce stood with Hepzibeth Macy, his intended bride, to publicly declare their intention of marriage before the members of New Garden Monthly Meeting in Guilford County, North Carolina. The ministers and elders appointed a two-person committee to investigate the couple’s “life and conversation” in order to approve their “clearness” for marriage and, a month later, with the committee’s recommendation secured, Pierce and Macy declared their intention a second time. On 26 August they were authorized to marry “according to the good order used among Friends,” and a second two-person committee was appointed to oversee the orderly completion of the wedding ceremony. Four days later, on 30 August 1775, the newlyweds exchanged vows in the meetinghouse before an assembly of family and friends. Nearly two months since they had first stood before the congregation, Thomas Pierce and Hepzibeth Macy completed the final step of the Quaker marriage process when the second committee reported an orderly ceremony and submitted a copy of their wedding certificate, signed by witnesses, for the monthly meeting’s official records. Joseph Perkins, the recorder, then transcribed the certificate into the bound volume that listed all of the marriages and births at New Garden Monthly Meeting (Figure 1). Thus began the union of a Pennsylvania-trained cabinetmaker with a Massachusetts-born wife that through complex migration patterns would profoundly shape the Quaker-made furniture of Piedmont North Carolina for the next fifty years.[1]

Together, Pierce and Macy represented two of the three dominant migratory patterns that formed the character of Piedmont North Carolina’s Quaker community. By the early 1750s, Quakers from southeastern Pennsylvania had begun to travel down the Great Wagon Road to reach the inexpensive but fertile farmlands of Carolina. With a rapidly growing population of Pennsylvania Quaker families—Brazeltons, Hocketts, Mendenhalls, Osbornes, and Thornburghs—the material culture of the New Garden settlement closely resembled its motherland. In fact, the very site of Thomas Pierce and Hepzibeth Macy’s wedding, New Garden Monthly Meeting (Figure 2), had been founded in 1754 in direct response to this wave of migration and very purposefully named after the New Garden Monthly Meeting in Chester County, Pennsylvania.[2]

In the early 1770s, New England Quakers like Hepzibeth Macy and her extended family gave up the seafaring life of Nantucket Island and joined the Pennsylvania settlers on many of the same fertile farmlands of North Carolina.[3] This second migratory wave brought with it New England names—Barnard, Coffin, Gardner, Macy, Starbuck, Way—and the two groups, united by a common faith, quickly intermarried.

The third and final wave of Quaker migration to Piedmont North Carolina came after the American Revolution when Quakers officially adopted opposition to slavery as a core tenet of their religious belief, and a significant number of Friends from the heavily slave-owning sections of eastern North Carolina and Virginia moved to the Piedmont. Thus, members of the Bundy, Fentress, Henley, Nixon, Symons, and Winslow families became part of the Piedmont Quaker community. Once again, intermarriage between these groups came quickly, and by the early nineteenth century, these three distinct strains of Quaker migration had united to form a blended culture.

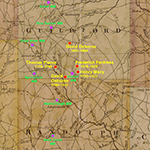

The distinctive furniture of this area was first presented by the late John Bivins in a pioneering article in the May 1973 issue of The Magazine ANTIQUES, “A piedmont North Carolina cabinetmaker: The development of regional style.”[4] Bivins noted that a number of case pieces—consisting of chests, chests of drawers, clock cases, desks, desks and bookcases, high chests, and high chests on frame—comprised a unique group that combined Pennsylvania design characteristics with histories of descent among the Quaker families of the region. Based on the discovery of a “William Needham” signature in one of the group’s most quintessential furniture forms, a pitch pedimented high chest on frame (Figure 3), Bivins attributed the group to Jesse Needham (c.1772–1839), a woodworker who was born among Quakers in eastern North Carolina and lived among Quakers in northern Randolph and southern Guilford counties, but was not himself a Quaker. New information gleaned in the more than fifty years since John Bivins’s article—among deeds, inventories, meeting records, and the discovery of a previously unknown cabinetmaker’s account book—has shed new light on this topic and better identified Jesse and William Needham. Moreover, it has revealed the complex network of Quaker cabinetmakers responsible for this unique regional furniture group, its colonial Pennsylvania origins, and its gradual evolution to incorporate design elements from all three of the migratory patterns that comprised the Quaker community of southern Guilford County (Figures 4 and 5).

Thomas Pierce of Pennsylvania: Founder of the Guilford Quaker School

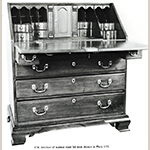

George Pierce (1714–1775) and Lydia Roberts (b.1721) were married before witnesses at Kennett Monthly Meeting in Chester County, Pennsylvania, on 31 March 1740. As third-generation Pennsylvanians whose families had arrived with William Penn in the late seventeenth century, they could not have foreseen that within a few decades, not one, but four of their seven sons would travel down the Great Wagon Road to North Carolina. However, they were keenly aware that their families had close ties to the cabinetmaking business. Lydia’s stepfather, Thomas Carleton (1699–1792), and her half-brother, Thomas Carleton Jr. (1732–1803), were documented furniture makers in the Kennett area. George Pierce’s cousin, Joel Baily Sr. (1697–1775) and his son, Joel Baily Jr. (1732–1797), were two of the best-known Quaker cabinetmakers in eighteenth-century Chester County. A desk and bookcase (Figures 6 and 7) signed and dated by Baily Sr. in 1732 and 1747 (probably his own property) attests to his active involvement in the cabinetmaking trade during the second quarter of the eighteenth century.[5] The Pierces and the Bailys were related by marriage to yet another, well-documented furniture making family in the region that included brothers Robert (c.1712–1770) and Daniel Eachus (c.1716–1774), and their nephew, Virgil Eachus (c.1767–1839).[6] Pointing to the very close connections between these families, when Robert and Daniel Eachus’s mother penned her will in 1758, it was witnessed by two members of the Baily family, and she named Thomas Carleton as her executor.[7] While George Pierce and Lydia Roberts’s wedding certificate does not survive, it almost certainly listed the names of several cabinetmakers among the Baily, Carleton, and Eachus families.

A high chest on frame signed and dated by Robert Eachus in 1755 (Figure 8) and a high chest on frame signed and dated by his nephew Virgil in 1789 (Figure 9) illustrate the early appearance and gradual evolution of this Chester County form.[8] Over a roughly thirty-year period, the drawers of the bottom section dissolved as the upper case was elongated with an additional row of drawers, the cabriole legs with trifid feet were shortened, and the scalloped frame, now without drawers, became even more decorative. This 1789 example is particularly notable because of its very close resemblance to the undated North Carolina example signed by William Needham (Fig. 3). Side by side, these two chests illustrate the very close cultural connections that existed between Chester County, Pennsylvania and Piedmont North Carolina cabinetmaking. As John Bivins noted in his original article on this group, “it has been said that piedmont North Carolina was culturally an extension of greater Pennsylvania, and to a certain extent that is true of its decorative arts.”[9]

George and Lydia’s son, Thomas Pierce (1752–1800), was born into this cultural milieu. Like his parents, he was a Quaker who attended Bradford Monthly Meeting (Figure 10) and grew up surrounded by cabinetmakers among the Baily, Carleton, and Eachus families. His father was a prosperous middling farmer who, with the labor of his seven sons and two indentured servants, cultivated approximately three hundred acres along the banks of the Brandywine River. As a younger son, Thomas was apprenticed to a trade and, while there is no firm evidence for his cabinetmaker training, the logical assumption would be his father’s cousin, Joel Baily Jr., who also lived, worked, and worshipped within the verge of Bradford Meeting. Additional facts and surviving objects support this hypothesis. In 1784, the young Virgil Eachus was accepted into Bradford Meeting as an apprentice and, although his master was not explicitly named in meeting records, the most logical assumption would be Baily, who was the meeting’s best-known cabinetmaker at the time. Eachus remained at Bradford from 1784 until 1792, when he transferred his membership to Chester Monthly Meeting.[10] Thus, the high chest on frame signed by Eachus and dated 1789 probably represents the work of Baily’s shop during Eachus’s apprenticeship. Its similarity to North Carolina examples suggests that Thomas Pierce also trained in his cousin’s shop and transported his knowledge of Chester County furniture forms when he moved to Carolina.[11]

On 14 October 1774, Thomas Pierce petitioned Bradford Monthly Meeting for a certificate to transfer his membership to North Carolina’s New Garden.[12] His request was approved the following month on 18 November. Approximately twenty-one years of age, Thomas was following the footsteps of his older brother Robert (c.1745–1812), a cooper, who had moved to Carolina in 1766 and acquired 500 acres on Hickory Creek in southern Guilford County (Fig. 5).[13] When their father died the following year, in 1775, George Pierce left Thomas and Robert cash bequests, instead of land, and forgave a £30 debt owed him by Thomas.[14] In 1776, their younger brother Jesse Pierce received Bradford’s permission to join them at the recently organized Center Monthly Meeting.[15] Finally, after being disowned by the Quaker faith of his ancestors for “drinking strong liquor to excess” and for “quarreling & striking a man,” their youngest brother, David Pierce (c.1760–1833), also moved to Guilford County where in 1793 he purchased land from the Osborne family close to Robert’s property on Hickory Creek.[16] Thus, the four Pierce brothers had joined the long chain of Quaker migration from Pennsylvania to North Carolina that began in the 1750s.

The committee that had reviewed Thomas’s request included Richard Buffington (1718–1781), a Bradford Quaker who had seen many of his own siblings and neighbors make the same journey. In fact, it is possible that Thomas Pierce had already sojourned to North Carolina at least once. A letter written from Guilford County on 25 April 1772 by Richard’s younger brother, Peter Buffington (1735–1815), to their elder brother, John Buffington (1712–1774), noted that “Thomas Pearce [sic] was at my house this day,” and that the two were contemplating a trip to Georgia to inspect a parcel of land that Peter had recently purchased.[17] A millwright, Peter had written to his brother John in 1765 that he was living with James Mendenhall (1718–1782), a Bradford Quaker and mill owner who had recently transported himself, plus a wife and six children, to New Garden.[18] The following year, Buffington noted that he was building a sawmill for John Mendenhall (1721–1800), another recent Bradford arrival, and suggested that his brother should secure a wagon to bring his entire family to North Carolina.[19] Peter repeated the invitation in 1767 and promised that if John and his family came to North Carolina they would be well fed and entertained with “jonecake [sic]”.[20]

On 25 February 1775, slightly more than three months after he had petitioned Bradford for his removal, Thomas Pierce arrived in Carolina and presented his certificate to New Garden Monthly Meeting, which noted that it was officially “read and Accepted.”[21] Thomas quickly found a bride in Hepzibeth Macy, who had arrived from Nantucket in 1771, and New Garden records document the six children born to them between 1776 and 1785. In December of 1775, however, Thomas and Hepzibeth transferred their membership to Center Monthly Meeting, located approximately ten miles to the south of New Garden and near the land acquired by Thomas’s older brother, Robert.[22] Thomas Pierce never seems to have owned land in Guilford County. He is not mentioned in any surviving deed or land record, except for one brief reference in a 1779 land entry to Samuel Frazier for 350 acres on Bull Run which noted that it contained an “improvement” by Thomas Pierce.[23]

Thomas’s life and career in North Carolina is only documented in Quaker meeting records, and the most important of these is his return to New Garden from Center Monthly Meeting on 29 November 1777 with his wife, their first-born child, and “an Apprentice Lad” named David Osborne (1759–1833).[24] Osborne’s family had moved to Carolina from Warrington Monthly Meeting in York County, Pennsylvania, in the early 1750s, and had been among the earliest members of Center Meeting. An orphan, Osborne lived and trained with Pierce for at least three years, until 1780, when he turned twenty-one and petitioned New Garden to return to his own extended family at Center.[25] In 1787, Osborne received from his father’s estate a 159-acre parcel of land in a deed that identified him as “David Ozbun, Cabinet Maker.”[26] This document allows us to positively identify Thomas Pierce’s own cabinetmaking trade, which he then taught his young apprentice, and qualifies David Osborne as the first native-born cabinetmaker of Guilford County.

Only three surviving furniture objects can be attributed to Thomas Pierce. The most important is a high chest on frame (Figure 11) that descended in the family of Hepzibeth Macy’s cousins, the Anthonys, and bears such a marked resemblance to Chester County work that it could only have been made by a cabinetmaker with first-hand knowledge of the form. While other North Carolina-made examples of the high-chest-on-frame form came later, this is the only one known with trifid feet, non-reeded quarter columns, and the same three-over two-over four drawer configuration that we have already seen on Virgil Eachus’s signed work (Fig. 9) from Bradford township.

Like Eachus’s example, Pierce’s features at the top an elongated center drawer between two smaller side drawers; however, the scalloped shaping at the bottom of Pierce’s frame is unlike any other known Chester County example, suggesting that it was probably designed by Pierce after his arrival in North Carolina. Made of walnut with tulip poplar, the underside of the center top drawer of this piece features an important signature and date, “J. M. Anthony 26thOctober 1897.” James Milton Anthony (1834–1900) was a member of Center Monthly Meeting whose great-grandfather, James Anthony (1733–1798), had migrated from Bristol County, Massachusetts to North Carolina in the mid 1770s. James settled on Hickory Creek land that directly adjoined David Osborne’s family and was close to Thomas Pierce’s brother, Robert. After the death of James’s first wife, he married Mary (Macy) Way at Center Meeting on 26 December, 1776. Upon his own death, James left the Hickory Creek property to his son Obed Anthony (d.1836) and his land on nearby Polecat Creek to his son Jonathan Anthony (1767–1842). When Jonathan died, his probate inventory listed this piece as the “one Stand of Drawers” that was purchased by his son, Jonathan G. Anthony (1812–1882), James Milton Anthony’s father.

While the Anthony and Macy families were closely related and may have been proud of their New England heritage, it cannot be denied that this high chest on frame traces its lineage to Chester County, Pennsylvania. Although they were made more than four hundred miles apart, due to Thomas Pierce’s Quaker migration pattern, we can assume that the Anthony family’s high chest on frame and Virgil Eachus’s signed and dated example of 1789 are roughly contemporary.

A walnut gate-leg table (Figure 12) descended in the family of Joseph Iddings (1751–1828), who moved from Bradford to New Garden at the same time as Thomas Pierce and also signed his marriage certificate to Hepzibeth Macy in 1775. Based on that very close association, and the table’s style and presumed date of manufacture, it may be another example of Pierce’s early North Carolina production.

A late eighteenth-century walnut desk (Figure 13) collected in Guilford County might also be the work of Thomas Pierce. The configuration of its block-fronted interior with fluted document drawers and arched valances closely resembles the interiors of many desks made in Chester County during the second half of the eighteenth century, including an example (Figure 14) signed by Pierce’s relation, Robert Eachus, and this configuration became a typical form in Guilford County. The presence of the two candle drawers to support the mitered-batten fallboard is another design and construction detail often seen in Chester County; however, the carved and applied pinwheel decoration on the two candle drawers is unusual. In Chester County, pinwheel decoration is a stylistic element associated with Nottingham township, where it was sometimes used on the candle drawers of desks (Figure 15), but especially on the pediments of high chests and clock cases attributed to the Quaker cabinetmaker Jacob Brown (1746–1802). In fact, one of these clock cases (Figures 16 and 17) is known to have belonged to George Pierce’s cousin, Moses Brinton (1725–1789).[27] Thus, Thomas Pierce may be responsible for the introduction of this particular Chester County design element as well, which—as we shall see—created new opportunities for remarkable expression as Guilford County’s own vernacular style developed further in the nineteenth century.

The 1790 census for Guilford County suggests that at that time Thomas Pierce and his family lived on Hickory Creek with his brother Robert. While Thomas is not listed in the census, Robert Pierce’s household included two adult males living with four females and five male children.[28] Within five years, Thomas had left Guilford County to join his youngest brother David’s new exploits in the metal industry in Wythe County, Virginia. Robert and David Pierce sold their land in Guilford County. In 1795, Thomas received a land entry for 300 acres on the South Fork of the Holston River.[29] In 1800, however, he died intestate, and the Wythe County court named his widow Hepzibeth and his eldest son George as the administrators of his estate. In addition to personal possessions, Thomas’s probate inventory listed a variety of tools—forge tools, smith tools, cooper tools, and most importantly, “1 set of Joiners tools” valued at $85.00, which was the single most valuable item in his estate.[30]

For roughly twenty years, from 1775 to 1795, Thomas Pierce had operated a cabinet shop in Guilford County, living and working among the Quaker communities of New Garden and Center meetings. He was the first professional cabinetmaker in the area, and thus the founder of the Guilford County Quaker Cabinetmaking School. His legacy involved the introduction of Chester County form and design into the regional vernacular, a legacy that continued into the first quarter of the nineteenth century through the production of his documented apprentice, David Osborne, and his wife Hepzibeth’s cousin, Henry Macy (1773–1846), a highly successful—but until recently unknown—cabinetmaker whose work suggests that he too trained in Pierce’s shop.

David Osborne: Guilford County’s First Native-Born Cabinetmaker

David Osborne’s family had been among the earliest wave of Quaker migration to the Carolina Piedmont. On 3 February 1753 his grandfather, Matthew Osborne (1697–1783), was received from Warrington Monthly Meeting in present-day York County, Pennsylvania into the Piedmont’s first Quaker meeting, Cane Creek, founded in 1751.[31] Matthew was quickly joined by his sons, William (c.1725–1768) and Matthew Jr. (1729–1816). In 1754, the Osbornes’ land along Deep River and Hickory Creek fell within the verge of the newly formed New Garden Monthly Meeting, as more Quaker meetings were established to accommodate a growing population, and in 1773, it fell within that of Center Monthly Meeting for the Quakers living in southern Guilford and northern Randolph counties.[32] When David’s father William Osborne died in 1768, David and his siblings became orphans under the supervision of their uncle Samuel Osborne (c.1731–1807) and William Reynolds (1738–1787), whose families had also migrated from Pennsylvania to North Carolina in the early 1750s.[33]

Osborne’s cabinetmaking career is more delineated than Thomas Pierce’s as he appears in the New Garden records in 1777 as Pierce’s “apprentice Lad,” is identified as “David Ozbun, Cabinet Maker” in the 1787 deed, and in 1798 accepted the recently orphaned John Stanton (b.1792) as his own apprentice in the “shop joiner’s trade.”[34] David Osborne married Elizabeth Thompson, and they had at least eight children. He plied his craft and bought and sold land along Deep River in southern Guilford County until 1801, when he transferred his family’s membership from Center to New Garden and relocated to a 273-acre tract he had recently acquired on the waters of Buffalo Creek (Fig. 5).[35] Located approximately ten miles to the north of his original homestead, this move placed him within the sphere of a different clientele. The reason for his move might be suggested in the recently discovered account book of Henry Macy, which documents that in 1799—two years before Osborne’s relocation—Osborne contracted with the 26-year-old Macy to help him find walnut and assist with the fabrication of a coffin.[36] Macy was clearly the up and coming cabinetmaker of the Center community.

On 30 June 1804, Osborne left Guilford County altogether by joining the massive wave of Quaker migration to the non-slave owning free territories of the Midwest, asking New Garden for certificates for himself and his family to the recently formed Miami Monthly Meeting in Warren County, Ohio.[37] Ironically, in 1816, they transferred again from Center to New Garden, but this time from Center Monthly Meeting in Clinton County, Ohio to New Garden Monthly Meeting in Wayne County, Indiana, both of which were named for the North Carolina meetings that had been the original birthplace of many of their members.[38] According to Osborne family records, David Osborne died in Perry township of Wayne County, Indiana, on 31 May 1833. There is no information whether he practiced the furniture making trade at any point after his North Carolina departure, and like many Carolina cabinetmakers who migrated to the Midwest, he may have simply given up woodworking for agriculture.[39]

There is no evidence that until his removal in 1804 David Osborne had much traveled beyond the approximately ten-mile distance from New Garden to Center meetings. Therefore, if Thomas Pierce was the founder of the Guilford Quaker School and the originator of its Pennsylvania roots, David Osborne was the cabinetmaker most capable of translating it into a native backcountry expression. With very little eighteenth-century Guilford County furniture available for study, two pieces stand out as the likely production of Osborne’s hand.

One of the most remarkable pieces of early North Carolina Piedmont furniture is the desk and bookcase on frame (Figure 18) that was first published in The Magazine ANTIQUES in May 1941 and, according to oral tradition, descended in the Lamb family of northern Randolph County.[40] Like the Osbornes, the Lambs were among the earliest members of Center Monthly Meeting, and related to David Osborne by marriage as his uncle and guardian, Samuel Osborne, married Elizabeth Lamb on 6 July 1761.[41] The exact provenance of this piece is unknown, but if it is the “1 Bureau & Bookcase” that sold for the remarkably high sum of $15.55 at the estate sale of Colonel Isaac Lamb (1784–1862) of Randolph County, then it was probably made for his parents, Samuel Lamb (1758–1846) and Hannah Beeson (1759–1836), who were married at Center Monthly Meeting on 31 December 1777.[42]

Stylistically, this object can be described easily as one of the most individualized expressions of early backcountry furniture, and with the possible exception of the Anthony family high chest (Fig. 11), bears the added distinction of being the earliest known example of case-on-frame construction in the North Carolina Piedmont. Made between 1780 and 1800, it conforms to David Osborne’s work dates and his close circle of family and patrons in the Center community. John Bivins once described its “peculiar” combination of eighteenth-century Chinese- and Gothic-style details, and the “highly vernacular” construction of its removable pagoda-like pediment with a scalloped central opening surmounted by seven turned finials. As he noted, “in addition to the highly vernacular pediment, the massive construction of the piece—thick carcass sides, corbelled interior partitions, and drawer frames—indicates a cabinetmaker with a rural background.”[43] Also indicative of its rural origins, the drawer bottoms are attached to the backs of the frames with wooden pegs instead of forged nails. While it is tempting to try to place this object in an international design context, a more apt description might be that this piece reflects the subtle and not-so-subtle influences of a Pennsylvania-trained craftsman on an apprentice who was born in rural North Carolina and trained in his shop for only three years during the highly disruptive period of the American Revolution.[44]

A more careful analysis of the desk and bookcase’s design elements highlights its relationship to Osborne’s master, Thomas Pierce. The scalloped frame and cabriole legs resemble those on Pierce’s high chest on frame for the Anthony family (Fig. 11), albeit compressed to accommodate the desk. The configuration of its stepped interior bears a resemblance to the earlier desk and bookcase (Figs. 6 and 7) made and signed by Pierce’s relation, Joel Baily, in Chester County—a design concept that Pierce might have brought with him to Guilford County in the 1770s. The scalloped pediment, on the other hand, may reflect a rural cabinetmaker’s attempt to replicate an urban design element that he has never seen and only heard described, but it perhaps more fairly represents the rural cabinetmaker’s creativity and professional ambition in a less socially constrained rural environment.

By 1795, Osborne would have owned and operated his own cabinet shop for roughly fifteen years, and with Pierce’s removal to Wythe County, Virginia, he would have been—for at least a short time—the region’s dominant cabinetmaker. Thus, he might well be the maker of a tall clock case (Figures 19 and 20) that was made for the Nantucket-born Quakers, Barzillai Gardner (1751–1829) and his wife, Jemima Macy (1750–1833), of New Garden Monthly Meeting. The clock works were made and signed in York County, Pennsylvania by Jonathan Jessup (1771–1857), a Guilford County-born clockmaker who had trained under the York County Quaker craftsman, Elisha Kirk (1757–1790). Upon his master’s death, Jessup decided to remain in Pennsylvania to pursue his trade, instead of return home to his family. Jessup’s mother, Ann (Matthews) Floyd Jessup (1738–1822) was a respected minister at New Garden and one of the witnesses at Thomas Pierce and Hepzibeth Macy’s wedding.[45] Jessup’s professional reputation and strong North Carolina connections undoubtedly led the Gardners to send their own son, Barzillai Jr. (1778–1815), to Pennsylvania for his training as a clockmaker and silversmith. On 26 April 1794, the young Barzillai was given a certificate transferring his membership from New Garden to York Monthly Meeting in Pennsylvania.[46] Two years later, on 16 November 1796, Gardner became a runaway apprentice, and Jessup speculated in a newspaper advertisement that the eighteen-year old was probably headed home to North Carolina.[47] Because the clock bears an inscription on its face that proclaims its origins, “Jonathan Jessup/York Town” and “Made for Barzillai and Jemima Garner [sic],” it must have been made during the successful years of Gardner’s apprenticeship from April 1794 to November 1796; the walnut case must have been made in Guilford County sometime shortly thereafter.

In form, the clock case differs significantly from those made in either Chester or York counties of Pennsylvania, but it bears a very close resemblance to those that came later in Guilford County (see Figs. 31, 42, and 44). In many ways, it reflects the same sturdy construction observed with the Lamb family desk and bookcase (Fig. 18), most notably with its heavy reliance on wooden pegs instead of iron nails. While later Guilford County clock cases featured fully enclosed arched hoods, this clock’s bonnet is simply an arched facade with an applied molding that turns slightly upward at the two ends in a vaguely chinoiserie style that echoes the Lamb family desk and bookcase’s unique pediment.

The Gardner family clock and case combine multiple cultural elements. The clock was made in York County, Pennsylvania, by a clockmaker who was born in Guilford County. His patron lived in Guilford County, but was born in Nantucket. The patron commissioned the case from a Guilford County-born cabinetmaker, who had been trained by a craftsman from Chester County, Pennsylvania. Perhaps no other object better presents the tripartite cultural blend of Guilford County’s early Quaker community.

Henry Macy Jr. of Nantucket: Proliferator of the Guilford Quaker School

Henry Macy was born to Quaker parents, Henry Macy (1737–1816) and Sarah Swain (1728–1788) at Nantucket on 6 March 1773.[48] At the age of twelve, he packed his belongings and moved with his parents and siblings to Guilford County, North Carolina, where they joined a host of other Nantucket Quakers who had made the same journey a dozen years earlier.[49] In 1786, Henry Macy Sr. purchased a 150-acre farm on Polecat Creek (Fig. 5), a branch of Deep River that crossed the Guilford-Randolph County line and ran by Center Monthly Meeting. The meetinghouse was located only a few miles from the Macys’ new farm.[50] As Henry Sr. had worked as a ship carpenter at Nantucket, and the prospects for ship carpentry were slim in Piedmont North Carolina, Henry Jr. seems to have been apprenticed to his cousin Hepzibeth Macy’s husband, Thomas Pierce, to the more suitable trade of cabinetmaking.[51]

The late 1790s were a pivotal time in Henry Macy Jr.’s life. Around 1795, his presumed master, Thomas Pierce, left Guilford County and opened a path for Macy to pursue his trade with far less competition. On 20 November 1796, he married Mary Jenkins at the nearby Center meetinghouse and started a family that grew to include eight children.[52] For our purposes, however, the most important fact may be that in 1798 he purchased a bound volume of plain paper to use as an account book for his cabinetmaking business, and over the next forty-six years recorded his clients’ accounts and the multiplicity of furniture forms that he produced for them (see the Appendix for an abstract of furniture forms found in the account book). Macy was proud enough to inscribe its title page, “Henry Macy his Book Bought the 28th of the 7th mo. the year of our Lord 1798.”

Macy’s account book demonstrates that he was the cabinetmaker responsible for the Piedmont North Carolina furniture group first identified by John Bivins in The Magazine ANTIQUES. Its list of patrons includes both Quakers and non-Quakers who all lived in southern Guilford and northern Randolph counties, and all within an approximately ten to fifteen mile radius of Macy’s shop and Center Meeting. It also provides a deeper insight into the region’s early economy showing objects purchased on credit and paid over time with a combination of cash and bartered goods and services. In addition to its lists of clients and furniture forms, however, it also identifies many of the apprentices and journeymen who worked in Macy’s shop. These include William McKenzie (w.1801), Frederick Fentress (w.1808–1818), Jesse Hendrix (w.1812), and Samuel Brazelton (w.1815–1817).[53]

An account in 1818 for a young man named William Needham suggests that he too worked in the Macy shop. It included “Stocking one Set of Bench plains” for twelve shillings (Figure 21). It is now clear that the signature on the high chest illustrated in Bivins’s article (Fig. 3) was not that of a patron named William Needham, as once speculated; instead, it represents an inscription by the 21-year-old William Needham (b.1797), who was a younger son of the said Jesse Needham (c.1774–1839) and the nephew to Henry Macy’s apprentice and soon-to-be son-in-law, Frederick Fentress (1791–1874).[54] Based on the close family connection, Needham probably worked as a journeyman in the Macy and Fentress shop in the late 1810s. A recent, much closer examination of the inscription reveals that it actually states in full, “William Needham’s Joiner Work.”[55]

The scale of Macy’s multi-person shop is perhaps best demonstrated by a simple chest (Figure 22) with multiple signatures and inscriptions. In construction, it is typical of the Macy shop’s work with exposed dovetails on the front of the case, dovetailed battens on the lid, and straight bracket feet with a spur design that was typical of the shop. However, one of the small hidden drawers in the till has multiple inscriptions that identify David Pritchett (1795–1858) and one of Macy’s other documented journeymen, Samuel Brazelton (1795–1860), as its makers. The two young men wrote across the drawer, “State of North Carolina/Gilford County/September 30th 1816/ Drawer made by Samuel Brazelton/David Pritchett” (Figure 23). Born in Pasquotank County in eastern North Carolina, Pritchett and his family were among the many non-slave owners who had migrated to the Piedmont; he went on to become a saddler and appears to have only passed through the shop. Macy’s account book records multiple credits to Samuel Brazelton “for Work” from 1815 to 1817, at which time Macy stocked for him “one set of Bench plains” plus multiple molding and smoothing planes for two pounds, sixteen shillings.[56]

As noted, Macy’s rising dominance in the local furniture trade was suggested in his 1799 account to assist his cabinetmaking predecessor, David Osborne, with the procurement of walnut and the completion of a coffin for an unidentified client. But it seems further proven by Macy’s 1801 account to make the coffin for Osborne’s own aunt, Elizabeth (Lamb) Osborne. That year David Osborne’s uncle and former childhood guardian, Samuel Osborne, paid Henry Macy one pound to fabricate the coffin “for thy Wife.”[57]

Many of the objects once attributed to Jesse Needham, but now assigned to the shop of Henry Macy document the ongoing Chester County influence that had been established by Thomas Pierce. Most significant among these are the high chests on frame that, with only a few slight modifications, bear an uncanny resemblance to the Anthony family high chest on frame (Fig. 11) attributed to Pierce and the signed and dated Chester County example (Fig. 9) made by Virgil Eachus in the 1780s. One example that descended in the Hodson, Murphy, and Causey families is typical of the shop’s production (Figure 24), and it may be the “I Case of Drawers” listed in the probate inventory of Macy’s neighbor, Solomon Hodson (1776–1860), who had married Tamar Dicks (1772–1850) on 30 November 1797 at Center Meeting. Hodson was a documented patron as Macy recorded in 1800 that Solomon owed him six shillings for a coffin “for thy Child.”[58] The shape of the scalloped skirt on its supporting frame is virtually identical to the earlier Thomas Pierce example (Fig. 11), and it features the same three-over two-over four drawer configuration with an elongated center drawer flanked by two narrower drawers on the top row. The only significant differences are the profile of the cornice molding, with a cyma curve instead of a cove, and the narrow slipper feet that terminate the cabriole legs, instead of the trifid feet seen on the Pierce and Chester County examples. Narrow slipper feet were typical of many Rhode Island and Massachusetts high chests (Figure 25), and the appearance of this particular design detail is perhaps a nod to Henry Macy’s New England background.[59]

Likewise, a desk that descended in the Clodfelter and Frazier families (Figure 26) features a block-fronted interior that is obviously derived from the earlier example attributed to Thomas Pierce and closely related to the Chester County desk signed by Robert Eachus (Fig. 8). Its ogee bracket feet include the same spur profile seen on a two-over three drawer chest of drawers that descended directly in the cabinetmaker’s own family (Figure 27), as well as the straight bracket feet of the chest signed by Samuel Brazelton and David Pritchett (Fig. 22). The most significant difference between the three desks is that the Pierce and Eachus examples feature the typical mitered-batten fallboard that was common in Pennsylvania and the South. Macy’s example, however, uses the straight-batten method that was typical of Massachusetts and Rhode Island work – perhaps another bow to his New England origins.

In these two pieces, the high chest on frame and the desk, we can see Macy taking the early Chester County furniture forms that he would have learned from Thomas Pierce and adjusting them to include New England design and construction details, such as slipper feet and straight-batten fallboards.

A corner cupboard attributed to Macy (Figure 28) that descended in the family of Jesse Davis (1756–1829) tells an even more complex story. Like many members of Center Monthly Meeting, Davis’s family had migrated from Pennsylvania. His father, James Davis (1736–1805), was originally from East Bradford, near Thomas Pierce’s birthplace, and was described in Center records as “one of the early settlers of Randolph County.”[60] On 11 January 1781, Jesse married Elizabeth Reynolds (1758–1815) at the Center meetinghouse, and they subsequently lived on Muddy Creek in northern Randolph County.[61] In 1799, Jesse and Elizabeth built a new house there and engaged the region’s 26-year-old, Nantucket-born cabinetmaker, Henry Macy, to help them complete it. Macy’s account book records that Jesse Davis owed him six pounds for “Work Done upon thy House.”[62] The corner cupboard stands out as an important transitional object. Its asymmetrical triangular back suggests that it was custom built for a very particular corner. The raised panel doors recall those on the Lamb family desk and bookcase on frame (Fig. 18), now attributed to David Osborne. The applied pinwheel decoration to the pitch pediment, however, conjures the candle drawers on the earlier desk attributed to Thomas Pierce (Fig. 13)—incorporating for pure decoration the small brass knobs that had served as functional handles on the desk drawers. The applied decoration and the beveled dentil molding would become important hallmarks of the Macy shop later seen on many of its most ambitious pediments. Interestingly, the row of arched glazed panels at the top of the upper doors is reminiscent of the corner cupboards and dish presses made in eastern North Carolina during the second half of the eighteenth century, and an early sign of the growing influence of Tidewater migrants who began streaming into the Piedmont in Guilford and Randolph counties during the 1780s and 90s.

Several objects illustrate Macy’s willingness to experiment with applied decoration to his pediments. A walnut and poplar tall chest (Figure 29) descended in the Farlow and Brown families of northern Randolph County; it is probably the “1 case drawers” listed in the estate inventory of Isaac Farlow (1767–1860).[63] It is also probably contemporary with the 42 pounds, 16 shillings debt owed Macy by Farlow in 1808 and recorded in the account book as “Work Done on thy House.”[64] On this piece, the pinwheel decoration has morphed into two carved neoclassical quarter fans, and they flank the central motif—a highly stylized fleur de lis—that became a quintessential element of the Macy shop’s decorative vocabulary. The high chest on frame in MESDA’s collection (see Fig. 41) combines these same motifs with the beveled dentil molding and uses of the small brass knobs as decorative center points for the carved quarter fans. A desk and bookcase (Figure 30) signed in red pencil “SB,” presumably for the shop’s apprentice and journeyman Samuel Brazelton, and dated 1812, also unites the beveled dentil molding with the stylized fleur de lis and carved quarter fans on its pitch pediment, and features the brass knobs with carved pinwheel decoration with on its two candle drawers.

The Macy account book records multiple tall clock cases made by Henry Macy, and many for his first cousin, Thomas Swain (1769–1826), who appears to have been the local clockmaker. According to his account book, Macy produced for him one clock case in 1796, two in 1798, and at least eight more over the next several years.[65] Presumably, Swain supplied patrons with the works for each of these cases; however, at least nine of Macy’s clients purchased their own clock cases directly from the cabinetmaker. Born on Nantucket to Nathaniel Swain (1727–1781) and Bethiah Macy (1733–1791), Thomas Swain was an active member of Center Monthly Meeting and a founding officer of the North Carolina Manumission Society.[66] In 1818 he joined the massive wave of Quaker migration to the non-slave owning free states of the Midwest and transferred his and his family’s membership to White Water Monthly Meeting in Wayne County, Indiana.[67] There, the Swains continued their clockmaking trade, as an 1884 history of Wayne County noted that his younger son Job Swain (1795–1846) was “for some time engaged in the watch and clock business, and there are still in use in Richmond brass clockswhich he made and which are good time-pieces.”[68]

The two cousins, Henry Macy and Thomas Swain, probably collaborated on the tall clock and case (Figure 31) made in 1797 for their mutual first cousin, Henry Way (1759–1815). Way was the son of Henry Macy Sr. and Bethiah (Macy) Swain’s sister, Mary (Macy) Way Anthony (1729–1808).[69] After their removal from Nantucket, the Ways and the Swains were close neighbors on Hickory Creek, and multiple members of the Anthony, Macy, Swain, and Way families had signed the wedding certificate of Henry Way and Charlotte Anthony at Center meetinghouse on 26 December 1778.[70] The ownership of Way’s clock is unmistakable as the brass dial is fully inscribed, “Henry & Charlotte Way 1797” (Figure 32). Presumably made at approximately the same time, the case’s enclosed arched hood with a simple cove molding without dentils may represent Macy’s earliest known cabinet work, and presages the more ornate clock cases that became a hallmark of his shop’s production (see Figs. 42 and 44).

Henry Macy continued to enjoy the patronage of his Way cousins. In 1798, Henry Way ordered a case of drawers from Macy for six pounds, four shillings, and two years later, in 1800, he acquired chests for two of his children, the less expensive one pound, four shillings version was for his 19-year-old son Joseph (b.1781) and the more expensive two-pound version was made for his 12-year-old daughter, Rachel (b.1788).[71] In 1798, Henry’s elder brother, William Way (1756–1839), purchased his own tall clock case from Macy for three pounds, four shillings, despite the fact that William’s wife, Abigail (Osborne) Way (1756–1829), was a first cousin of the region’s other cabinetmaker, David Osborne.[72] By 1800, Henry Macy had clearly established himself as the go-to cabinetmaker among the highly inter-related families of Center Monthly Meeting.

Frederick Fentress: Coastal Influence and Decline of the Guilford Quaker School

Frederick Fentress (1791–1874) was born in Randolph County, North Carolina immediately following his parents’ migration from the eastern part of the state. William (c.1750–c.1800) and Mary (Howard) Fentress had lived in Pasquotank County on the Albemarle Sound, and in the early 1790s made their trek with close friends and relations to the Piedmont. The Fentresses, along with their neighbor, John Needham (1745–1830), had been listed as non-slave owners in the late eighteenth-century tax lists and censuses for Pasquotank County.[73] William Fentress and John Needham were not Quakers, but had been closely aligned with the Quaker community ever since the marriage of their siblings, Pharaoh Fentress (d.1811) and Elizabeth Needham, who converted to Quakerism and married at Pasquotank Monthly Meeting on 21 February 1770.[74] Pharaoh and Elizabeth were among the first coastal Quakers to resettle to the Piedmont when they requested a transfer of their membership from Pasquotank to Center Monthly Meeting in 1777.[75] By the early 1790s many of their Quaker and non-Quaker relations had joined them in the Quaker Crescent region of northern Randolph and southern Guilford counties.

William Fentress’s death shortly after his resettlement left Frederick an orphan, and by 1808 he was living with Henry Macy and his family in Guilford County, obviously working as an apprentice to the cabinetmaking trade. Macy’s account book carefully documents the expenses for Fentress’s clothing and schooling.[76] By 1811, Frederick’s account with Macy (Figures 33 and 34) began to record the credit he received for cabinet work, such as “Labour Don on a Coffin,” “one days work at 4/per day,” “Work Done on a Case of Drawers,” and “making a Chest price 5 Dollars & 50 Cents.” In 1812, he received credit for “Making a Clockcase price 10 Dollars.” Eventually, Frederick achieved the dream of virtually every young apprentice, to marry the master’s daughter. In 1815, Frederick Fentress married Sarah Macy (1792–1837), although there is no record of Sarah ever receiving any discipline from the elders and ministers of Center Monthly Meeting for marrying “out of unity” with a non-Quaker.[77]

Fentress never converted to Quakerism, but fully embraced the family business. Rather than return with Sarah to northern Randolph County, he purchased land on Polecat Creek to be close to his father-in-law and his father-in-law’s shop. When he acquired 65 acres from one of the Macy’s neighbors in 1815 (Fig. 5), his father-in-law witnessed the deed.<[78]

In 1818, Fentress took his own apprentice, Joab Edging, aged fourteen, and entered into an agreement with the Guilford County Court that he would be responsible for teaching Joab to “Read, Write & Cypher thro the Rule of Three” and in exchange to “Learn him the Art & Mistery of a Cabinet Business.”[79] Fentress may have been responsible for the appearance of other eastern North Carolinians in the family cabinet shop, such as the previously mentioned David Pritchett and William Needham, whose families also hailed from Pasquotank County. In fact, William Needham was the son of Frederick’s older sister, Sarah Fentress, and her husband Jesse Needham, thus he was actually Frederick Fentress’s nephew.

The coastal influence on the shop’s production was first seen in the Davis family corner cupboard (Fig. 28) made around 1799 with its arched glazed panels on the front doors, but that influence continued to manifest itself over many decades. Perhaps most dramatically is the appearance of the cellaret, or bottle case, form that was used to store alcoholic beverages. This furniture form was typical in the homes of eastern North Carolinians, even Quakers, but would have been virtually unknown to either Thomas Pierce or David Osborne. In 1815, Macy charged John Beard sixteen shillings for one.[80] Few Piedmont North Carolina cellarets are known to have been made or to survive, but among them is one that can be safely attributed to Henry Macy’s shop (Figure 35) due to its cabriole legs with slipper feet, exposed dovetails on the sides of the case, dovetailed battens on the lid, and large carved quarter fans ornamenting its façade—all typical Macy techniques.

A desk and bookcase (Figure 36) that descended in the Bell and Walker families of northern Randolph County perfectly symbolizes how the Guilford County Quaker School had evolved to incorporate multiple design elements. It is probably the “Newest Desk” bequeathed by the wealthy land and mill owner William Bell (c.1735–1822) to his nephew Robert Walker (c.1780–1850) in Bell’s 1822 will and subsequently acquired by Walker’s granddaughter, Sarah E. (Walker) Osborne (1850–1950).[81] Bell appears to have been deeply involved with the launch of Fentress’s career, loaning him $844.62 cents in 1815—when Fentress married Sarah Macy and purchased his first tract of land on Polecat Creek. At the time of Bell’s death Fentress still owed him $464.92.[82] Stylistically, the row of arched glazed upper panels at the top and the row of wooden blind panels at the bottom of the bookcase doors are features typically seen on corner cupboards and dish presses made in eastern North Carolina and Tidewater Virginia. Meanwhile, its block-fronted interior and candle drawers with applied pinwheel decoration harken back to the Chester County desks made by Robert Eachus and later by Thomas Pierce (Figs. 13 and 14). Its boldly turned finials bear a vague resemblance to those created by David Osborne for the Lamb family’s desk and bookcase on frame (Fig. 18).

By the time Henry Macy died on 30 March 1844, an era had ended.[83] Macy would have been one of the few people remaining in Guilford County who had known and once worked with Thomas Pierce in the 1780s, and he would have been among a handful whom recalled David Osborne as a neighbor and friendly competitor in the 1790s. His probate inventory noted that he owned “1 Set of joinering tools” and “1 Set of Smith tools belonging to the deceased” and his son, David Macy.[84] The furniture industry had changed, and the old vernacular walnut furniture made in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries had given way to the new mahogany veneered sideboards and bureaus that were being made by one of Frederick Fentress’s other nephews, Jesse Needham Jr. (1805–1892), who had acquired property and established a cabinetmaking business in the new and bustling town of Greensboro.[85] Fentress himself gave up cabinetmaking all together to pursue more lucrative investments in banking and the copper and gold mining industries. In 1874, he died a wealthy man with only a cross-cut saw, some carpenter’s tools, walnut plank, and “1 lot patterns” listed in his estate inventory as reminders of his and his father-in-law’s former careers as cabinetmakers.[86]

During its fifty-year heyday, from 1775 to 1825, the Guilford County Quaker School inspired numerous imitators. Working on nearby Alamance Creek, the young Scotch-Irishman Robert Matthews (c.1773–1825) made desks with candle drawers and applied pinwheel decoration like Pierce, straight-batten fallboards like Macy, and an interior fenestration that was similar to both Pierce and Macy (Figure 37).[87] In 1807, however, he picked up and moved to Maury County, Tennessee. Likewise, John Adams (c.1772–after 1834), a non-Quaker, made high chests (Figure 38) with pitch pediments similar to Macy’s Farlow family example (Fig. 29) for his Quaker and non-Quaker clientele in the northern part of Guilford County along Horsepen Creek.[88] Numerous cabinetmakers, both Quaker and non-Quaker, worked along the various branches of the Deep River in southern Guilford and northern Randolph counties during the early nineteenth century, fashioning wares that bore a close resemblance to those of Pierce, Osborne, and Macy, but usually with enough variation to distinguish them from the heart of the group. Imitation was the sincerest form of flattery.

Conclusion

Rooted in Chester County, Pennsylvania with branches grafted from Nantucket and coastal North Carolina, the Quaker furniture of Guilford County, North Carolina strongly reflected its diverse cultural background. Each of the region’s three major waves of Quaker migration impacted the look and design of its furniture. Once attributed to Jesse Needham, we now know that this group originated with Thomas Pierce, the cabinetmaker born in Chester County, Pennsylvania who arrived at New Garden Monthly Meeting in 1775. His locally born apprentice, David Osborne, then perpetuated the Chester County style he had learned under Pierce, but also experimented with its translation into a regional backcountry expression. Henry Macy added subtle New England influences from Nantucket, and kept an extensive account book that documented the cabinetmaking school’s broad range of furniture forms and its regional patrons, both Quaker and non-Quaker. Macy’s apprentice and son-in-law, Frederick Fentress, represented Tidewater influences from the eastern part of North Carolina that added a final element to the group—and all four of these men were closely connected to the Society of Friends through birth, membership, or marriage.

Many decorative arts scholars have speculated on the impact of the Quaker faith on aesthetics, how the Quaker concept of simplicity in religious worship and dress might have influenced its furniture.[89] While the interiors of Quaker meetinghouses were often characterized by a stark simplicity (Figure 39), the furniture made by Quaker craftsmen for their private clients often departs from this notion. Even in Piedmont North Carolina, the Quaker cabinetmakers could produce and their Quaker patrons commission the home furnishings we have seen with decoratively scalloped skirts and ornate pitch pediments with carved and applied ornaments. In this instance, regional identity trumped religious faith in the material culture of the domestic sphere, and Quaker cabinetmakers produced objects that reflected their ethnic origins and professional training, and furniture that was friendly to the regional preferences of their patrons—whether they hailed from Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, eastern North Carolina—or a combination of all three.

Robert Leath is Chief Curator and Vice President of Collections & Research at Old Salem Museums & Gardens. He can be reached at [email protected].

APPENDIX: Henry Macy Account Books, 1796–1844, Furniture Forms, Dates, Patrons, and Prices

Transcribed from the Henry Macy Account Books, 1796–1844, Macy/Zimmerman Papers, MSS. Collection #141, Series 2, folders 4-10, Greensboro History Museum, Greensboro, NC.

Architectural Work (16)

|

1797 |

William Macy |

1.10.0 – 6 Day Work upon Thy House |

|

1798 |

William Macy |

1.4.0 – Work upon thy House |

|

1799 |

Jesse Davis |

6.0.0 – Work Done upon thy House |

|

1800 |

John Stanton |

0.12.0 – Work on thy House |

|

|

William Field |

7.4.0 – Work done on thy House |

|

|

|

2.10.2 – Work done on thy House |

|

1801 |

Joseph Leonard |

0.4.6 – Work don on thy House |

|

1806 |

William Dicks |

6.10.0 – Labour Done on thy House |

|

1807 |

Daniel Sherwood |

8.12.0 – Labour Don on thy House $21.50 |

|

1808 |

Isaac Farlow |

42.16.0 – Work Done on thy House |

|

1813 |

John Jenkins |

2.18.0 – Shingling thy House |

|

|

Joseph Leonard |

0.5.0 – labor don on thy House |

|

1818 |

Frederick Fentress |

0.16.0 – 2 days work framing on thy store |

|

|

|

0.2.0 – 1.4 part of a days work on thy House |

|

|

Jonathan Hodson |

0.16.0 – 2 days a frameing on thy Barn |

|

1830 |

Nathan Chamness |

$5.50 – six days work on thy House |

Bedsteads (3)

|

1803 |

Levi Stanton |

0.14.0 – Pair of Bedsteads |

|

1812 |

Elisha Mendenhall |

0.16.0 |

Bottle Case (1)

|

1814 |

John Beard |

0.16.0 |

Bureaus (6)

|

1823 |

David Worth |

5.4.0 – for Ruth |

|

1824 – 26 |

William Beeson |

8 to 10 dollars each – 12 bureaus |

|

1825 |

Jonathan Worth |

14 dollars – nice |

|

1826 |

Jonathan Lamb |

11 dollars – paid John Macy, settled with Frederick Fentress |

|

1828 |

David Worth |

13.50 dollars |

|

1830 |

David Worth |

5.4.0 – for Everlinah |

Candlestands (3)

|

1799 |

William Dobson |

0.3.4 – a stand |

|

1807 |

Christopher Vickery |

0.8.0 |

|

1821 |

Thomas Carrow |

25 cents each for turning candlestand pillows |

Cases of Drawers (8)

|

1798 |

Henry Way |

6.4.0 |

|

1800 |

Eleanor Smith |

8.0.0 |

|

1801 |

William McKenzie |

3.0.0 – 8 dollars, credited for making a case of drawers |

|

|

|

1.4.0 – credited for work done on a case of drawers |

|

1803 |

Michael Wilson |

6.8.0 |

|

1807 |

Thomas Wilson |

6.8.0 – 16 dollars |

|

1808 |

Thomas Macy |

8.0.0 |

|

1811 |

Frederick Fentress |

0.4.0 – credited for work done on a case of drawers |

Chests (45)

|

1797 |

William Macy |

0.9.0 – poplar |

|

|

|

0.9.0 – one walnut box |

|

1798 |

John Beals |

1.4.0 |

|

|

Thomas Davis |

1.4.0 |

|

|

Mary Fluck |

0.12.0 |

|

1799 |

Mary Hodson |

1.4.0 |

|

|

Christopher Vickory |

2.8.0 – Chest & Table |

|

1800 |

Absalom Vickory |

1.8.0 – a chest & table |

|

|

Phebe Macy |

2.0.0 |

|

|

John Murphy |

1.4.0 |

|

|

Henry Way |

1.4.0 – for Jos. |

|

|

|

2.0.0 – for Rachel |

|

|

John Stanton |

2.0.0 |

|

1805 |

Francis Flanagan |

1.4.0 – 3 dollars |

|

|

Obed Anthony |

2.4.0 |

|

1806 |

John Beard |

1.16.0 – 4 ½ dollars |

|

1807 |

Jonathan White |

2.4.0 – 5 dollars |

|

1808 |

John Reynolds |

1.8.0 – 3 ½ dollars |

|

|

William Wiley |

2.4.0 |

|

|

James Hendrix |

0.12.0 |

|

|

Thomas Macy |

0.12.0 |

|

|

|

0.12.0 – poplar Chest for H. Davis |

|

1809 |

Obed Anthony |

2.4.0 |

|

|

Henry Macy |

5.4.0 – two Chests price 13 dollars |

|

|

Mary Frazier |

1.16.0 – Making Chest and finding Lock & Hinges |

|

|

Robert Woodborn |

2.4.0 – 5 ½ dollars |

|

|

Joseph Swain |

2.4.0 – 5 ½ dollars |

|

1810 |

Obed Anthony |

2.4.0 |

|

|

Job Worth |

2.0.0 – 5 dollars |

|

|

Robert Woodborn |

2.8.0 – 6 dollars |

|

|

Libni Barnard |

4.8.0 – 2 Chest @ 5 ½ Dollars for Chest |

|

|

|

1.8.0 – one Chest at 3 ½ Dollars |

|

|

Nancy Stephenson |

1.8.0 |

|

1811 |

Henry Davis |

1.8.0 – 3 ½ dollars |

|

|

Daniel Sherwood |

0.12.0 |

|

|

|

0.12.0 |

|

|

Joseph Swain |

2.4.0 – 5 ½ dollars |

|

|

David Mabin |

4.16.0 – two Chests price 6 Dollars per Chest |

|

|

Sarah Davis |

2.4.0 – 5 Dollars & 50 Cents |

|

1817 |

Libni Barnard |

2.8.0 – 6 dollars |

|

1828 |

Jethro Swain |

$11.00 – 2 chests |

Clock Cases (23)

|

1796 |

Thomas Swain |

3.4.0 |

|

1798 |

Thomas Swain |

6.8.0 – two clock cases |

|

1798 |

Zeno Worth |

3.4.0 |

|

1798? |

William Way |

3.4.0 |

|

1801 |

Thomas Swain |

3.8.0 – 8 ½ dollars |

|

|

|

3.8.0 – 8 ½ dollars |

|

? |

Thomas Swain |

10.16.0 – three clock cases |

|

? |

Thomas Swain |

3.8.0 |

|

1801 |

William McKenzie |

1.14.0 – 4 ½ dollars, credited for making a c[lock] case |

|

1802 |

Thomas Swain |

3.12.0 – 9 dollars |

|

|

|

3.12.0 – 9 dollars |

|

1804? |

Jonathan Anthony |

3.12.0 – 9 dollars |

|

1806 |

John Beard |

3.12.0 – 9 dollars |

|

1807 |

Christopher Vickery |

3.12.0 |

|

1808 |

Silvanus Swain |

3.12.0 |

|

1811 |

Jesse Hinshaw |

3.12.0 |

|

1812 |

Frederick Fentress |

4.0.0 – 10 dollars, credited for making a clock case |

|

1814 |

Frederick Fentress |

4.0.0 – 10 dollars, credited for making a clock case |

|

1821 |

Jonathan Hodson |

4.8.0 – 11 dollars |

|

|

Mary Jenkins |

12 dollars |

Coffins (52)

|

1796 |

Thomas Swain |

0.7.0 |

|

1798 |

Obed Barnard |

0.6.0 – for thy Child |

|

|

Peter Ozborn |

1.0.0 – for thy Wife |

|

|

Joseph Hodson |

1.0.0 – for thy wife |

|

1799 |

Obed Barnard |

0.12.0 – for thy wife |

|

|

William Dicks |

0.10.0 – for thy Child |

|

|

David Orsborn |

0.16.0 – assisting and finding Walnut for a Coffin |

|

|

David Hodson |

0.6.0 – for thy child |

|

|

Obed Anthony |

0.16.0 – for thy Father |

|

1800 |

Isaac Hodson |

1.6.0 – for thy Wife |

|

|

|

0.6.0 – for thy Child |

|

|

Solomon Hodson |

0.6.0 – for thy Child |

|

|

Thomas Wilson |

1.0.0 – for thy wife |

|

|

John Stone |

1.5.0 – for thy Wife |

|

|

Michael Wilson |

1.10.0 – for the Deceased |

|

1801 |

Zeno Worth |

0.8.0 – for thy Child |

|

|

Samuel Osborn |

1.0.0 – for thy Wife |

|

|

Robert Hodson |

0.8.0 – for thy Child |

|

1803 |

Thomas Swain |

0.10.0 – for thy son Caleb |

|

|

|

0.12.0 – for thy wife |

|

|

Michael Wilson |

1.4.0 – for Jean Wilson |

|

1804 |

Matthew Osbon |

0.12.0 – for thy Wife |

|

1806 |

George Johnston |

1.0.0 – for thy Sister |

|

1807 |

Daniel Worth |

0.12.0 – for thy wife |

|

|

Daniel Sherwood |

1.0.0 – for thy wife |

|

|

John Hodson |

1.5.0 – for John Jenkins |

|

1808 |

William Matthews |

1.4.0 – for thy Wife |

|

|

|

1.8.0 – for the Deceased |

|

|

William Shannon |

1.6.0 – for the said Wm. Shannon Deceased |

|

|

Jonathan Parker |

1.4.0 – for thy mother |

|

1809 |

John Love |

1.0.0 – for thy mother-in-Law |

|

|

Joseph Barnet |

0.16.1 – for thy wife |

|

|

Levin Kirkman |

0.5.0 – for thy Child |

|

|

Obed Barnard |

0.8.0 – for thy Daughter |

|

|

David Worth |

0.8.0 – for thy Child |

|

1810 |

Michael Wilson |

1.4.0 – for thy Mother |

|

|

John Worthington |

1.4.1 – for the said John Worthington Deceased |

|

|

Benjamin Wilson |

0.5.0 – for thy Child |

|

1811 |

Benoni Mills |

0.16.0 – for thy mother |

|

|

Jonathan Parker |

0.8.0 – for thy child |

|

|

Job Worth |

0.7.0 – for thy child |

|

|

John Williams |

0.16.0 – for the sd. John Williams |

|

|

Michael Swaim |

0.10.0 – for thy Child |

|

1812 |

Joseph Worth |

0.16.0 – for the sd. Joseph Worth |

|

1815 |

William Dicks |

0.6.0 – for thy Child |

|

1821 |

Obed Anthony |

0.16.0 – for thy wife |

|

1826 |

William Beeson |

$4.00 |

|

1828 |

David Worth |

1.0.0 – for John Benson |

|

1830 |

David Worth |

1.8.0 – for thy Father $3.50 |

|

|

|

1.4.0 – for a black man $3 dollars |

|

1836 |

Samuel Osburn |

$4.00 – coffin for sd. S. 0. |

|

1837 |

James Lamb |

$5.00 – for wife |

|

|

|

$1.50 – for child |

Cradle (1)

|

1813 |

John Jenkins |

0.6.0 |

Cupboards (3)

|

1809 |

William Wiley |

4.0.0 – 5.0.0 with finding mountain for sd. cubbard |

|

1811 |

John Gamble |

4.9.0 – 11 dollars, 12 ½ cents |

|

1830 |

Nathan Chamness |

8 dollars |

Desks (8)

|

1799 |

Peter Field |

7.4.0 |

|

1800 |

Obed Anthony |

8.0.0 |

|

1803 |

Silvanus Swain |

8.0.0 |

|

1806 |

Zeno Worth |

2.8.0 |

|

1810 |

John Beard |

10.0.0 |

|

|

Libni Barnard |

7.4.0 – 18 dollars |

|

1812 |

Frederick Fentress |

1.11.0 – charged for three sets of desk mountings |

|

1818 |

John Leonard |

9.10.4 – 23.80 dollars for a desk mounted |

Desks and Bookcases (1)

|

1811 |

William Thom |

14.0.0 – for a desk and bookcase and table |

Dresser (1)

|

1805 |

Absalom Vickery |

2.12.0 |

Gun Stocks (3)

|

1818 |

Pritchard Albertson |

1.0.0 – stocking shotgun $2.20 |

|

1820 |

Richard Ozburn |

.50¢ – one gunstock |

|

1827 |

Levin Kirkman |

$2.00 – stalking a gun |

Sideboards (3)

|

1799 |

Thomas Swain |

2.0.0 |

|

1800 |

Thomas Swain |

3.6.0 – Table and sideboard |

|

1802 |

Thomas Swain |

1.16.0 – 4 ½ dollars |

Tables (18)

|

1798 |

William Dobson |

2.8.0 – falling leaf table |

|

1799 |

Thomas Swain |

1.12.0 |

|

|

Thomas Wilson |

1.0.0 |

|

|

Christopher Vickory |

2.8.0 – Chest & Table |

|

1800 |

Absalom Vickory |

1.8.0 – a chest & table |

|

|

John Stephenson |

0.16.0 – 2 dollars |

|

|

Thomas Swain |

3.6.0 – Table and sideboard |

|

|

Eleanor Smith |

1.4.0 |

|

1803 |

Joseph Barnet |

0.16.0 |

|

1804 |

Obed Anthony |

2.0.0 |

|

|

|

0.4.0 – a table top |

|

1808 |

Obed Anthony |

1.2.0 |

|

1809 |

Josiah Hodson |

1.0.0 |

|

1811 |

William Thom |

14.0.0 – for a desk and bookcase and table |

|

|

Thomas Johnson |

0.16.0 – price two Dollars |

|

1813 |

David Worth |

4.16.0 – 12 dollars set of tables |

|

1817 |

David Worth |

2.0.0 – 5 dollars tea table |

|

1829 |

Thomas Macy |

$5.00 |

Window Sashes and Shutters (24)

|

1798 |

William Way |

0.6.0 – 9 lights of Sash |

|

|

|

0.5.1 – 8 lights of Sash |

|

|

|

0.6.0 – 9 lights of Sash |

|

|

Paul Worth |

0.6.0 – 9 Lights of Sash |

|

|

William Macy |

0.6.0 – 9 Lights of Sash |

|

1800 |

John Stanton |

0.6.0 – 9 Lights of Sash |

|

|

|

0.5.4 – 8 Lights of Sash |

|

1801 |

William Worth |

0.10.8 – 16 light of Sash at /8 per light |

|

|

Joseph Leonard |

0.8.0 – 9 Light Sash & fitting them in |

|

1804 |

John Carter |

0.6.0 – 9 Lights of Sash |

|

1805 |

James Dicks |

0.4.0 – 4 Lights of Sash |

|

|

|

0.10.0 – one sett of window Shutters |

|

|

|

1.0.0 – a set of window shutters |

|

1806 |

John Beard |

0.8.0 – 12 Lights of Sash |

|

1807 |

Jesse Osborn |

0.10.0 – 15 Lights of Sash |

|

1808 |

Paul Beard |

0.6.6 – 9 Lights of Sash |

|

1809 |

Jethro Swain |

0.6.0 – 9 Lights of Sash |

|

1810 |

Job Worth |

1.4.0 – making 48 lights of Sash |

|

|

John Beard |

0.4.0 – 6 Lights of Sash at /8 per Light |

|

|

William Beard |

0.4.0 – 6 Lights at 0/8 per light |

|

1811 |

Thomas Swain |

0.8.0 – 12 Lights of Sash at /8 per light |

|

1812 |

John Beard |

0.6.0 – 9 Lights of Sash at /8 per Light |

|

1818 |

Joseph Swain |

0.7.0 – 9 Lights of Sash |

|

1824 |

Joseph Swain |

0.3.0 – 4 Lights of Sash |

Woodworking Tools (11)

|

1799 |

Jesse Davis |

0.2.0 – stocking one Smoth Plain |

|

1801 |

William Marsh |

0.14.0 – one set of Bench Plains |

|

1806 |

Job Worth |

0.4.6 – one jack plane |

|

1808 |

Joseph Way |

0.8.0 – one set of Bench plains |

|

1809 |

David Worth |

0.14.0 – one plow & Grove |

|

|

Aaron Coffin |

0.1.6 – finishing a jack plane |

|

|

|

0.4.0 – stocking a jointer |

|

|

|

0.8.0 – one work bench one dollar |

|

|

|

0.3.0 – stocking a smoth plain |

|

|

|

0.1.6 – one bevel Square |

|

1810 |

David Worth |

0.2.0 – a handle and Dressing a Plain |

|

1812 |

John Green |

0.1.0 – wheating a saw and faceing a Beed plain |

|

|

|

0.1.6 – wheting & seting a Saw |

|

|

|

0.2.6 – stocking Beed Plain |

|

|

|

0.1.0 – Wheting & seting a saw |

|

|

|

0.1.0 – turning 2 augur handles at /6 |

|

1813 |

John Green |

0.3.0 – stocking a jointer |

|

1814 |

John Green |

0.1.0 – making handle for jack plain |

|

|

|

0.1.0 – wheting & seting a saw |

|

|

|

0.2.6 – makeing molding plain |

|

1815 |

Joal Hodson |

1.19.0 – stocking 13 molding plains at 3/ |

|

|

|

0.3.0 – stocking one smothing plain |

|

|

|

1.13.0 – stocking 11 molding plains at 3/ |

|

|

|

0.6.0 – stocking 2 molding plains at 3/ |

|

|

|

0.3.0 – stocking 1 smothing plain |

|

|

|

0.3.0 – stocking one ogee plain for Jessee Ozun on thy account |

|

|

|

0.8.0 – stocking one plow plain |

|

|

|

0.6.0 – stocking one groveling plain |

|

1817 |

Samuel Brazelton |

2.16.0 – stocking one set of bench plains |

|

|

|

0.3.0 – stocking one upright smoth plain |

|

|

|

0.14.0 – stocking one plow & Grove plain |

|

|

|

1.4.0 – stocking 8 Molding plains @ 3/per plain |

|

|

|

0.3.0 – stocking one Molding plain 2 3/per plain |

|

1818 |

William Needham |

0.12.0 – stocking one sett of bench plains |

[1] William Wade Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, Volume I: North Carolina (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing, 1978), 558, 567. Digitized versions of all Quaker records cited in this article are available online by subscription: Ancestry.com., U.S., Quaker Meeting Records, 1681–1935 [database online]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

[2] Hinshaw,Quaker Genealogy, 487.With each of these infusions from Pennsylvania, New England, and the Tidewater, New Garden Monthly Meeting underwent a form of mitosis, splitting to form additional monthly and particular meetings to accommodate an expanding Quaker population. Center Monthly Meeting was established in 1773, followed by Deep River in 1778, Dover in 1815, and Hopewell in 1824. Deep River then split to form Springfield Monthly Meeting in 1790. Center Monthly Meeting gave birth to Back Creek in 1792 and Marlborough in 1816. Particular meetings attached to these monthly meetings added to the density of the region’s Quaker landscape. Together, these meetings formed a network of very closely inter-related Quaker communities that stretched throughout present-day Guilford and Randolph counties and were part of what has been called North Carolina’s Quaker Crescent. See Seth B. Hinshaw, The Carolina Quaker Experience 1665–1985 (Davidson, NC: North Carolina Yearly Meeting, North Carolina Friends Historical Society, 1984), 18–29.

[3] Silvanus J. Macy, Genealogy of the Macy Family from 1635–1868 (Albany, NY: Joel Munsell, 1868), 87. See also, Hinshaw, Quaker Genealogy, 558.

[4] John Bivins Jr., “A Piedmont North Carolina Cabinetmaker: The Development of Regional Style,” The Magazine ANTIQUES, May 1973, 968–973.

[5] The multiple signatures and dates in the cabinetmaker’s handwriting on this piece suggest it was probably the “Desk & Bookcase” listed for five pounds in the 4 June 1783 estate inventory of Joel Baily Sr. See Chester County, Pennsylvania, Estate Records, #2969; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/159829 (accessed 25 April 2018).

[6] John Pitts Launey, Early Families of Chester County, Pennsylvania, Vol. 2 (Westminster, MD: Willow Bend Books, 2000), 5–9, 126–129 and Margaret Berwind Schiffer, Furniture and Its Makers of Chester County, Pennsylvania (Exton, PA: Schiffer, 1978), 22–23, 74–75, 284–285, figs. 2, 3, 4, 37, 38, 79, 80, 146, 173, 174.

[7] Gilbert Cope, Abstract of Wills of Chester County, Pennsylvania: Volume II, 1758–1777 (Marshallton, PA: Jacob Martin, 1900), 1.

[8] Schiffer, Furniture of Chester County, figs. 173, 174.

[9] Bivins, “A Piedmont North Carolina Cabinetmaker,” 968.

[10] Martha Reamy, Early Church Records of Chester County, Pennsylvania, Volume I: Quaker Records of Bradford Monthly Meeting (Westminster, MD: Willow Bend Books, 2002), 194, 197, 209.

[11] Joel Baily’s estate papers support the hypothesis that he was familiar with the Chester County chest on frame form and would have made them in his shop. His 1797 probate inventory listed “1 Case of Draws with fluted corner” for 13 pounds, 33 shillings; “1 Case Draws walnut” for 10 pounds; “1 Walnut Case of Draws” for 12 pounds. His cabinetmaking tools included a turning lathe, a handsaw, tenon and compass saws, 12 chisels and gouges, a glue pot, 10 molding planes, a vice, a froe, and augurs. For Baily’s estate papers, see Chester County, Pennsylvania, Estate Records, #4608; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/159829 (accessed 25 April 2018).

[12] Reamy, Early Church Records of Chester County, 171 and Quaker Genealogy, 567.

[13] Ibid, 159, 161; Hinshaw, Quaker Genealogy, 413; and A. B. Pruitt, Abstracts of Land Warrants, Guilford County, NC, 1778–1932 (privately published, 2000), 127. On 7 April 1779 Robert Pierce received 500 acres on Hickory Creek that bordered the land of David Osborne’s uncle, John Osborne (1734–1819).

[14] Cope, Wills of Chester County, 551. Thomas Pierce’s probable master, the cabinetmaker Joel Baily, was also one of the appraisers of George Pierce’s estate. Chester County, Pennsylvania, Estate Records, #2959, available online: https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/159829 (accessed 25 April 2018).

[15] Reamy, Early Church Records of Chester County, 174.

[16] Ibid, 172, 175, 177, 178 and A. B. Pruitt, Abstracts of Deeds, Guilford County, NC, Books 3, 4, 5,& 6 (privately published, 2002), 165. On 11 July 1793 David Pierce purchased from Daniel Osborne a tract of 84 acres on the waters of Deep River. The deed was witnessed by his brother Robert Pierce and Peter Osborne (1769–1843), a cousin of the cabinetmaker David Osborne.

[17] Peter Buffington,Guilford County, NC, correspondence to John Buffington, 15 April 1772, #1036, Buffington-Marshall Papers, Chester County Historical Society, West Chester, PA.

[18] Peter Buffington, Rowan County, NC, correspondence to John Buffington, 13 October 1765, #757, Buffington-Marshall Papers, Chester County Historical Society, West Chester, PA.

[19] Peter Buffington correspondence to John Buffington, 16 August 1766, #789, Buffington-Marshall Papers, Chester County Historical Society, West Chester, PA.

[20] Peter Buffington correspondence to John Buffington, 2 March 1767, #809, Buffington-Marshall Papers, Chester County Historical Society, West Chester, PA.

[21] Hinshaw, Quaker Genalogy, 567.

[22] Ibid.

[23] A. B. Pruitt, Abstracts of Land Entries: Guilford County, NC, 1779–1796 and Rockingham County, NC, 1790–1795 (privately published, 1987), 6, 36. On 11 December 1779 Samuel Frazier entered a claim for 350 acres on Bull Run, a branch of Deep River in southern Guilford County, noting that the land included improvement made by Thomas Pierce. By 1785, this tract bordered land claimed by Hepzibeth Macy’s brother, Timothy Macy (1762–1848).

[24] Hinshaw, Quaker Genealogy, 565, 567.

[25] Ibid, 565.

[26] Pruitt, Abstracts of Guilford County Deeds, 76.