As some of the first Europeans to settle Virginia’s northern Shenandoah Valley, members of the Society of Friends helped lay the foundations for the region’s earliest built environment. Vestiges of these contributions can still be found in a number of Quaker homes and other structures dotting the northern Valley landscape (Figure 1). More recently, they can also be found in documentable examples of Quaker-made furniture from Frederick County and several other counties that emerged from Frederick in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.[1] The purpose of this article is to reintroduce “Old” Frederick County’s Quaker population—a heterogeneous mix of English, Welsh, and Scotch-Irish immigrants and their descendants—as some of the most prolific furniture makers in the Lower Shenandoah Valley prior to 1800, and particularly before the American Revolution. It also seeks to document some of the design characteristics that travelled with the Valley’s Quakers from their origins in the mid-Atlantic and specifically southeastern Pennsylvania, the heart of Quaker culture in America.

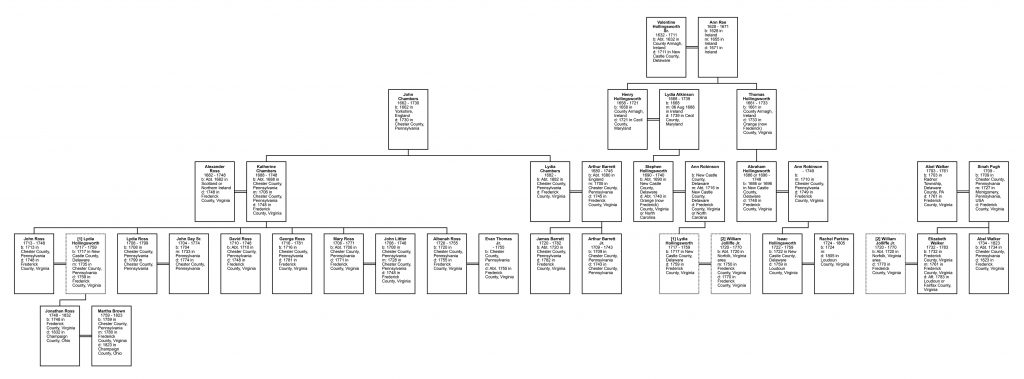

The concept for a Quaker settlement in the Shenandoah Valley first took root in the early 1730s under the leadership of business partners Alexander Ross and Morgan Bryan. Both were Friends in good standing at meetings in Chester County, Pennsylvania. Family traditions identify both men as immigrants from Ulster in Northern Ireland. On 28 October 1730, Ross petitioned the Council of the Colony of Virginia for 100,000 acres in the northern Shenandoah Valley, identified as “lying on the west & North Side of the River Opeckan & extending thence to a Mountain called the North Mountain & along the River Cohungaruton [Potomac River] & on any part of the River Sherundo [Shenandoah River] not already granted to any other Person.”[2] While seemingly a large request, the partners’ proposition aligned perfectly with the Virginia colonial government’s plans for the Shenandoah Valley. Officials in Williamsburg envisioned the Valley as a buffer between Tidewater Virginia interests and perceived threats from the Catholic French and Spanish and their Indian allies across the Appalachian Mountains. The advantage for the Quakers was not primarily the opportunity to freely practice their religion; after all, William Penn founded Pennsylvania as a haven for the Society of Friends in the colonies. Instead, the Ross-Bryan grant provided Quaker families the opportunity to acquire large tracts of cheap, fertile land that they could then parcel out to subsequent generations, a formula Valley Quakers adopted from their Pennsylvania cousins.[3]

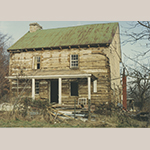

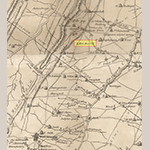

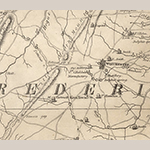

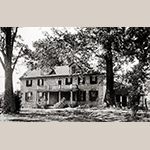

By the mid-1730s, Ross and Bryan had settled approximately seventy families on the land allotted them. The majority of families originated in Chester County, but also represented were settlers from Maryland, Delaware, southern New Jersey, and points further north.[4] The largest concentration settled primarily along Opequon Creek in what would become Frederick County, Virginia and Berkeley County, West Virginia, north of present-day Winchester (Figure 2). Despite the fact that the venture did not achieve the one hundred families originally required, permanent patents were issued for the lands in November 1735. Bryan acquired 2,134 acres on Mill Creek near today’s Bunker Hill, West Virginia. Alexander Ross, meanwhile, received 2,373 acres centered on a limestone spring in Clear Brook a few miles away. Close to the spring, Ross built a limestone house, first called Ross’s Spring but later renamed Waverly (Figure 3).[5]

With the establishment of so many Quaker families came the need for a meeting for worship. Ross again took the initiative in May 1734, petitioning East Nottingham Monthly Meeting in Chester County “on behalf of friends att [sic] Opeckon [shortly thereafter called Hopewell] that a Meeting for worship may be Settled among’st them.”[6] The Pennsylvania meeting granted Ross’s request in December of that year and a log meeting house was constructed on a ten-acre plot carved from his grant for that purpose. Authorization for a monthly meeting, granting Hopewell the authority to conduct its own business, followed the next year. With this status granted, Hopewell joined a hierarchy that simultaneously connected and reinforced the Society’s social, religious, and kinship structures, with authority emanating from southeastern Pennsylvania. Immediate supervision of Hopewell’s activities fell to the Quarterly Meeting at East Nottingham, where so many “first families” had originated.[7] On the larger scale, Hopewell (Figures 4 and 5) fell under the auspices of the Yearly Meeting at Philadelphia, the heart of Quaker culture and the largest style center in the British colonies.

A second wave of migration to the northern Valley came in the mid-1730s in the form of Scotch-Irish Quaker and Presbyterian families from central New Jersey. Known as the “Jersey Settlement,” these approximately two dozen families settled in western Frederick County along Back Creek at the foot of Great North Mountain (Figure 6). By 1745, most had moved on to settle the Yadkin River Valley in Piedmont North Carolina under the leadership of Ross’s former partner Morgan Bryan. But the presence of surnames with woodworking connections among Jersey settlers—Anderson, Branson, Price, and Pancoast—meant they likely contributed to the region’s growing decorative vocabulary (Figures 7 and 8).[8] The relationships forged in the Lower Shenandoah Valley also connected Virginia Quakers to a network of ideas and trade that spanned the length of the Great Wagon Road, from Philadelphia to Piedmont North Carolina.

Edmund Peckover (d.1767), a travelling minister and Friend, offers a view of the Quaker community in the Lower Valley a little less than a decade after its founding:

The place is called Opeckon or Shaunodore River, where many families have removed from Pennsylvania; and they have two pretty good meeting houses. Abundance of people often come in besides Friends, and it looks as though things went on pretty well amongst them. They have five or six public Friends. I think it has not been settled ten or twelve years at most. I believe they must enlarge their meeting houses. They are about sixteen miles apart.[9]

Peckover’s comments on expansion foreshadowed the smaller, preparative meetings that sprang up throughout Frederick County’s countryside in the 1730s and 1740s. Most of the meetings were indulged only for bi-weekly worship and many also doubled as the homes of prominent Quakers. So numerous were they, that they came to encircle the eventual county seat at Winchester (first founded as Frederick Town in 1738).[10] In 1777, while a prisoner of the Continental Congress, Philadelphia Friend Thomas Fisher put many of these small but important sites to paper by marking the homes of local Friends on a map, with Winchester at the center (Figure 9).

Three meetings besides Hopewell feature prominently in this discussion: Centre Meeting, founded by the Parkins/Perkins family just south of Winchester and completed in 1778; Mount Pleasant Meeting, established by the Fawcett family in 1771 near Cedar Creek in southwestern Frederick County; and Crooked Run Meeting, present as early as 1758 but indulged in 1761 along Crooked Run in present-day Warren County, Virginia.[11] Business meetings alternated between the Crooked Run site and Isaac Parkins’s Centre Meeting just south of Winchester. Unfortunately, none of the aforementioned meeting buildings still stand, but others that survived into the age of photography like Back Creek and Upper Ridge Meetings help contextualize these significant vernacular spaces (Figures 10 through 12).[12]

Shortly after arriving, Quakers quickly cemented themselves on the Valley’s landscape. As occurred with their forebears in southeastern Pennsylvania, Virginia Friends settled on choice land bisected by streams, such as Opequon Creek in the western end of the county. This planned settlement soon transformed into substantial wealth through land investments, milling operations (including saw and grist mills), and grain farming.[13] Wheat grown in the Shenandoah Valley reached international markets. From the 1780s through the early 1800s, for example, the Lupton family of Apple Pie Ridge in northern Frederick County shipped grain through kinship-based merchant networks in Alexandria, Virginia, to ports as far away as the West Indies and Lisbon, Portugal.[14] The travel-based Yearly Meeting system facilitated, expanded, and reinforced these connections across the mid-Atlantic region and throughout the Atlantic World, along with transmitting standards of style and form.[15]

Nothing from the 1730s pioneer generation has been found in either private or public collections. A photograph of a walnut gate-leg table (Figure 13) taken by local historian Dr. Alfred D. Henkel in the early twentieth century, however, might illustrate the earliest datable piece of furniture with provenance to Frederick County. It descended through the Hollingsworth-Parkins family at Abram’s Delight (Figure 14; see Appendix A for the Hollingsworth family genealogy). Progenitor Abraham Hollingsworth (1686–1748) and his wife Ann Robinson (d.1749) acquired the land on which the house sits from Alexander Ross in 1732. Their son Isaac (1722–1759) and his wife Rachel Parkins (1724–1805)—daughter of Isaac Parkins—inherited the property and constructed the eastern (right-hand) half of the Abram’s Delight house in 1754.[16] [17] The house’s hooded gable end features a date stone reading “I / H / R” [with the “H” centered above] / 1754” (Figure 15). Isaac Hollingsworth’s status as a Quaker minister meant the house served as a site for weekly meetings during his lifetime.[18]

Annie Hollingsworth (1844–1930) was the last family member to live in the home (Figure 16). After Annie’s death, the property passed to several cousins, who in turn sold it to the City of Winchester in 1943. The city purchased the property two years later primarily for its access to an on-site spring. City officials sadly chose to sell the contents of the house before turning over its operation to the Winchester-Frederick County Historical Society.[19] The sale chronicled generations worth of family objects. In the April 1945 sale advertisement, the Hollingsworth-Parkins table in question was described as “a 17th century gate leg table in walnut.”[20] A transcription of the buyers and their purchases at the Stewart Bell Jr. Archives in Winchester identifies the successful bidder as a “Mrs. Oates,” likely Mrs. Emsey Catherine Walker Oates (1879–1961) of Winchester, Virginia and Hampshire County, West Virginia. The table sold for $425.00, less than a high chest of drawers at $975.00 (illustrated in Fig. 30) and a secretary and bookcase possibly dated 1775 at $430.00.[21]

Definitive conclusions are impossible to make without inspecting the table in person, but one theory dovetails nicely with family history. The table’s turnings are evocative of examples made in early eighteenth century New England, possibly eastern Massachusetts (Figure 17).[22] A “Pilgrim century” table in colonial Backcountry Virginia would be very unusual, except that Rachel Parkins’s family had New England roots.[23] [24] The table could have travelled with a direct or collateral member of the Perkins/Parkins family until it came to Rachel Parkins Hollingsworth or a later descendant at Abram’s Delight at an unknown date.[25] If the table is indeed a Massachusetts-made Perkins/Parkins piece, its narrative links Virginia’s earliest settlers with a Quaker network that spanned the length of Britain’s North American colonies.

The table was among other early objects at the 1945 Abram’s Delight sale. Not listed in the newspaper article but found in the transcription of the sale was also a “chest of drawers came from England six brass handles on, 2 off.” While perhaps truly a European chest that migrated with the Hollingsworths or Parkinses, it seems more likely this might have instead been an early eighteenth-century Delaware Valley or perhaps even New England piece brought to the Shenandoah Valley by one of the families (similar to the chest illustrated in Figure 18). A handful of other pieces sold in 1945 have returned to Abram’s Delight over the years, including a four-drawer cherry chest of drawers (or bureau), a cherry bird-cage candlestand probably made in Winchester, and most recently a walnut paneled corner cupboard with applied quarter-round moldings framing the doors (Figures 19, 20, and 21). The cupboard’s interior ochre-colored paint scheme has largely disappeared from the shelves’ upper side but remains largely intact on the underside (Figure 22).[26] Much more needs to be done to trace those Hollingsworth-Parkins family pieces still in private collections.[27]

Furniture Prior to 1750—Joiner Alexander Ross (ca.1682–1748)

Identifiable woodworkers came with the first waves of Quaker migration to the Shenandoah Valley in the 1730s. Of the approximately 105 cabinetmakers, joiners, carpenters, and other allied tradesmen documented as working in Winchester and Frederick County before 1775, twenty-nine (twenty-seven percent) can be directly identified in Hopewell or other local Quaker records.[28] An additional eighteen craftsmen (seventeen percent) bear surnames common to Hopewell and its circle of smaller, preparative meetings. The remaining fifty-eight craftsmen represent lesser percentages (fifty-six percent total) of smaller ethnic and religious groups, including German-speaking Lutherans and Reformed, Scottish and Scotch-Irish Presbyterians, and Englishmen loyal to the established church.[29] At the forefront of the Quaker craftsmen is the same Alexander Ross who led the migration from Pennsylvania. Ross’s presence in Frederick County in the early 1730s preceded other documented woodworkers by almost a decade.

According to family tradition, Alexander Ross was born in Scotland or Northern Ireland about 1682 (see Appendix A for the Ross family genealogy). He was left orphaned around eleven years old, and Chester County records reveal that Philadelphia merchant Mauris Trent brought him to the colonies as an indentured servant in 1693. The Chester County Court of Common Pleas bound Ross to English lastmaker Caleb Pusey (b.ca.1650–1727) of Upland in the same year.[30] Ross served his apprenticeship with Pusey until the standard age of twenty-one, around 1703, at which point he abandoned last making and pursued the joiner’s trade.[31] Several land indentures and other records recorded in Chester County over the next couple of decades confirm Ross’s status as a “Joyner.”[32]

Ross married Katherine Chambers of Chichester Township three years after completing his apprenticeship with Pusey.[33] Katherine was the daughter of John Chambers (1662–1730), a yeoman from Yorkshire, England. Over the next ten years, the couple engaged in a series of land speculations. They eventually settled on Conowingo Creek near the Maryland border by 1716. The Rosses transferred their membership to Newark Monthly Meeting upon purchasing their new farm, and two years later their area fell under the auspices of the newly established New Garden Monthly Meeting in West Nottingham Township. Ross appears as a landholder in West Nottingham tax records continually from 1718 to 1730.[34] From this location, Ross began planning the Virginia migration with Morgan Bryan.

Despite being a major figure in the Quaker migration to Virginia, very little is known about Ross’s time there after 1732. Only once did Ross sell land from his 2,373-acre grant to an individual outside of his immediate or extended family. On 21 August 1739, he sold 396 acres to John Nickline.[35] At that time the land was still in Orange County. Ross recorded his will with the new Frederick County court a decade later in October 1748, and it was probated in December of that same year, meaning he died sometime in the intervening months. Several Friends witnessed his will, including James Wright Sr., Robert Hutchings, and his sister-in-law Lydia Barrett. Ross was likely the victim of an unidentified epidemic running through the Hopewell-Opequon community. Several neighbors and immediate family members—including his sons David and John, son-in-law John Littler, and wife Katherine Chambers—also succumbed within a few weeks.[36] Perhaps because of the turmoil befalling the Opequon community, Ross’s probate inventory was either not taken or not recorded in Frederick County will books. The only specific reference to Ross’s personal estate in his will involves an enslaved man named Nero. Nero was to be retained amongst Ross’s three sons John, David, and George, and was not to be sold out of the family. His place within the Ross household is unknown; he could have helped on the farm, with Ross’s joined work, or both.[37]

Alexander’s inventory was not taken, but those of his son John Ross and son-in-law John Littler were. Their inventories offer some of the best evidence for furniture forms the family might have produced. The presence of ten shillings, three pence worth of “Sundry Carpenters tools” suggests that John Ross was a carpenter, perhaps working alongside his father. John also owned a few pieces of furniture, including six chairs, a table, a dough trough and box, and a “Walnut Chest wth Drawers under it.”[38] This chest over drawers is not known to survive, but a walnut paneled rail and stile example made in 1746 for Robert and Ann Lamborn of London Grove in Chester County might be a good substitute (Figure 23).

While probably not a woodworker, the inventory of Ross’s son-in-law John Littler offers a greater diversity of forms. Like John Ross, Littler owned a “Chest with Drawers under it.” He also owned:[39]

|

A Cloaths press |

1 Desk |

|

2 old spinning wheels |

1 Chest |

|

A Linnen wheel |

1 looking glass |

|

Kitchen Table |

An old Chest |

|

9 Chairs |

|

Littler also owned other property that probably aided his extended family’s woodworking efforts, including a saw mill centered on a plantation he dubbed “New Design.”[40]

Joiners in this period often extended their talents to other projects like architectural joinery, which is perhaps the best place to search for evidence of Alexander Ross’s surviving work. The most convincing case remains in the circa 1745 James Barrett House in northern Frederick County (Figure 24).[41] The Barretts were closely linked to the Ross family. James’s father Arthur Barrett (1680–1745), a tailor by trade, married Katherine Chambers Ross’s sister Lydia at Concord Monthly Meeting in 1705.[42] Arthur was taxed continually in East Nottingham from 1718 to 1734, but by May 1739 the Barretts had followed the Rosses to Virginia.[43] Arthur established his home on the western slope of Apple Pie Ridge off Old Baltimore Road, present-day U.S. Route 677 (Figure 25). His sons began building their own homes over the next few years in close proximity to their parents. In fact, before his death in 1745, Arthur’s home might have been a staging ground for his children’s construction projects. Unused lumber was noted throughout his house in his 1745 estate inventory, including “in ye Cellar” (valued at 4s.6), “in the Lower Room (£1.4.6), and mixed in with “Sundry other Goods” (£6.10.6.).[44] Several local historians have placed the construction of James’s home around or shortly after Arthur’s death in 1745, suggesting the wood might have been incorporated into the present limestone house. Arthur Barrett’s house was torn down in the 1990s, but the current owners of the James Barrett House purchased much of its interior woodwork and incorporated it into that house.

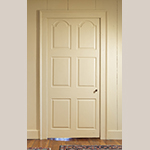

The James Barrett House’s interior has changed with time, but still extant from the first phase of construction are several four and six-paneled doors on the first and second floors (Figures 26 and 27). The uppermost panels on each of the original doors have arched and beveled tombstone tops, a decorative element found in interior architecture and even some furniture made in the Nottingham area of Chester County. A line-and-berry inlaid, double dome-top desk and bookcase made for the Montgomery family of Chester County makes a good comparison for the latter (Figure 28). Alexander Ross’s close relationship with the Barrett family make him a strong candidate to have executed the James Barrett House’s woodwork, or at least its paneled doors.[45][46] Later features from the Barrett House speak to the evolution of a Quaker home in the Valley. Sometime in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, an unknown craftsman added a pair of unique side-by-side drawers inset under the windowsills in the earliest part of the house (Figure 29).[47]

Much of the rest of Alexander Ross’s possible work is speculative. His woodworking skills, leadership role within the monthly meeting, and close proximity to Hopewell (Ross’s Spring/Waverly is within sight of the building) also make him a strong candidate to have made furniture for the first log meeting house and possibly constructed its interior. Unfortunately, little evidence survives from this time to document the building’s early appearance and furnishings. The first meeting house burned sometime in 1757, prompting the construction of the present two-story limestone building by master mason Thomas McClun in July 1759. The earliest Hopewell records survived the fire and were entrusted to William Jolliffe Jr. (b.ca.1720–1770), Hopewell’s third meeting clerk and second husband to John Ross’s widow Lydia Hollingsworth. Jolliffe stored the records at his home, a clapboard dwelling called the Red House for its bright red paint. The Red House stood on land formerly owned by Alexander Ross very close to Hopewell.[48] In a cruel twist of fate, the Red House also burned not long after reconstruction at Hopewell began, destroying all 1734–1759 records.[49]

Establishing Form After Mid-Century

Furniture makers and consumers continued to bring expectations of form and ornament with them down the Great Wagon Road over the second half of the eighteenth century. Mary Hutton (d.1774) of Chester and Berks counties is an excellent example. Mary was the daughter of Nehemiah Hutton and Sarah Miller, members of New Garden Monthly Meeting in Chester County. The Huttons transferred their membership to Exeter Monthly Meeting upon its founding in 1737, where Mary met and married Mordecai Ellis (1723–1785).[50] The Ellises and their six children moved to Virginia in 1773, requesting a certificate to Hopewell in April of that year.[51] Mordecai Ellis served as an elder at Hopewell and was actively involved with Centre Meeting in Winchester.[52]

Mary Hutton’s extended family, through both the Hutton and Miller lines, connected her to an expansive network of Chester County joiners, carpenters, and other woodworkers. Her maternal grandfather, John Miller, was a joiner in the New Garden area prior to his death in either 1714 or 1715. Joel Baily Sr. (1697–1772), father of West Marlboro cabinetmaker Joel Baily Jr. (1732–1797), was a witness to Miller’s will.[53] The will also identifies Joseph Hutton, Nehemiah’s brother and husband to Sarah’s sister Mary Miller. Several members of Joseph’s line entered the woodworking trades, including his son, cooper Thomas Hutton. After the death of his first wife, Thomas remarried to Irish Quaker Katherine Hiett. Three of their sons—Jesse, Hiett, and Thomas Jr.—worked as cabinetmakers or joiners in New Garden Township in the last quarter of the eighteenth century.[54]

In their notable work Paint, Pattern, and People, authors Wendy A. Cooper and Lisa Minardi identified several pieces of furniture, both large and small, made or used by the Huttons and allied families in Pennsylvania. Unfortunately, none of Mordecai and Mary Ellis’s furnishings are known to survive. Mordecai’s 1785 inventory in Berkeley County lists only farm equipment, grains, livestock, and a small number of personal objects.[55] The Pennsylvania-made objects serve as useful examples of forms that the couple might have brought to Virginia or commissioned locally. Particularly, a tall chest of drawers signed by Mary’s great-nephew Hiett Hutton (d.ca.1833) resembles several Frederick County examples from Quaker families (not illustrated, see Cooper and Minardi, Paint, Pattern & People, Fig. 1.14, p. 13).

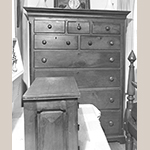

One of the best documented of these Virginia chests descended in the Hollingsworth family at Abram’s Delight. It is one of the few objects to return to the site (Figure 30). The chest’s secondary woods (tulip poplar and possibly chestnut) reflect its Pennsylvania cousins. The dust boards and drawer sides, backs, and bottoms are poplar. The horizontal backboards are probably chestnut and are nailed to the case sides. With the exception of the uppermost-center drawer, which has a lock, the upper two belts of drawers are accessed by now-missing spring locks nailed to the bottoms. A pencil inscription on the side of one of the full-length drawers reads “Sarah Hollings worth / [illegible] Va”. The inscription likely refers to Isaac and Rachel Hollingsworth’s granddaughter Sarah (1781–ca.1852), who grew up at Abram’s Delight alongside her twelve siblings. Sarah’s parents Jonah Hollingsworth (1755–1801) and Hannah Miller (1755–1836) built the western (left-hand) side of the house around 1800 to better accommodate their expanding family. The chest might date to the house’s expansion. Both the Hollingsworth chest and the Hutton examples have three-over-two-over-four drawer arrangements with original chinoiserie brasses. They also have applied, fluted quarter columns and stand on bracket feet (these have been replaced on the Hollingsworth chest, but likely were copied from the originals and with Nottingham-style drilled brackets like those described below). The aforementioned structural and ornamental elements carried into Frederick County and Winchester-area cabinetmaking through the early nineteenth century (Figures 31 and 32).

Other common furniture forms similarly borrow stylistic elements from Chester County and specifically Nottingham-area traditions. One of the most explicit parallels can be found on a chest with a recovery history in northern Frederick County (Fig. 32). The chest’s feet feature bracket cusps that are partially drilled and which return almost to the foot extensions (Figures 33 and 34). These features appear on case pieces from the Octoraro Creek area, part of the Nottingham School of furniture identified by Wendy Cooper and Mark Anderson (Figure 35).[56] Like some examples of Nottingham area furniture, the base molding and the feet of the chest are integral. The chest has been stripped down to the bare yellow pine, but evidence of the original red paint can be found in the joints and in the pine’s grain structure. The family history of this chest has unfortunately been lost, but it was collected in an area heavily settled by Quakers.

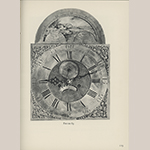

A surprisingly large number of tall case clocks survive from Frederick County, perhaps because of their universal functionality across generations. Many have movements signed by or attributed to Goldsmith Chandlee (1751–1821), the oldest son of Nottingham clockmaker Benjamin Chandlee Jr. (1723–1791). Goldsmith worked first in Stephensburg, also called Newtown and now Stephens City, in southern Frederick County (ca.1775–1782) and later in Winchester (ca.1782–1821). Once in Winchester, Chandlee established a foundry, where he made mathematical and surveying instruments (Figures 36 and 37). With his many talents, Goldsmith Chandlee is arguably the Shenandoah Valley’s most distinguished Quaker craftsman.

Several clocks, one from Chandlee’s Stephensburg period and two from his time in Winchester, have cases that speak to the transference of Pennsylvania traditions into the Shenandoah Valley. The location of the first clock is currently unknown, but local historians have long thought it contains Chandlee’s earliest Valley-made movement (Figures 38 and 39). The primary use of mahogany suggests that the case might be second generation and slightly later than the 1775–1782 brass-faced movement it houses. The attached moon dial prevented Chandlee from applying a brass signature boss that appears on other clocks signed by him (see Fig. 41 and Fig. 51). Instead, either Chandlee or the cabinetmaker set a boss mounted on glass and bounded by heart-shaped brass into the case door. This unusual treatment may or may not be original. The moldings on the base panel closely resemble those on numerous clocks from the Nottingham School of joinery in Chester County (see Fig. 60). Not surprisingly, many of this clock case’s Pennsylvania counterparts house movements made by Goldsmith’s younger brothers Ellis (1755–1816) and Isaac (1760–1813).

The second clock, from Chandlee’s Winchester period, likewise has a case that mimics forms from the Nottingham School of joinery (Figures 40, 41, and 42). While Nottingham-area clock cases often have removable, fully enclosed coffin-top bonnets (Figures 43 and 44), the Chandlee clock’s tympanum is blind only up the apex of the applied scrolls. Lack of wear on the top suggests the casemaker never intended a fully enclosed hood. The top of the tympanum board and the hood corners were also drilled for now-missing finials. Several Nottingham-made clocks rest on short, squat cabriole legs, but for at least part of the Chandlee clock’s life the case sat on a walnut framed base that is currently detached but still associated with it. Variations of this Nottingham-area form travelled down the Great Wagon Road as far south as the Cane Creek Settlement in Piedmont North Carolina as documented by June Lucas.[57]

Made primarily from cherry, the third clock case blends southeastern Pennsylvania features with those from other areas (Figure 45). The overall form of the arched pediment hood recalls New England clocks made from the 1750s through the 1770s (Figures 46 and 47).[58] But the tapered colonnettes with stepped rings resemble several Pennsylvania clocks, including one example in the Chester County Historical Society collection with works signed by Joshua Humphreys. The Humphreys clock dates to about 1765 during the clockmaker’s brief stay in Charlestown Township in northeastern Chester County. Unlike the Humphreys clock, however, the colonnettes on the Chandlee clock are freestanding and are not integral to the hood door. The finials on the Virginia clock are likely replacements but might have been copied from or inspired by the originals.

The preference for older, traditional styles in case furniture into the 1780s speaks to the conservatism of many Virginia Quaker makers and consumers. The clocks and their embellishments also speak to the intersections between furniture making and allied trades like architectural joinery, all part of a larger cultural landscape cultivated and sometimes enforced by the monthly meeting. Unifying decorative elements like the arched base panel on the first clock also appear as headers on the uppermost drawers of some high chests with local histories (Figure 48) and in interiors like that of the James Barrett House mentioned earlier.

Jonathan Ross (1748–1832) Continues a Tradition

Alexander Ross’s grandson Jonathan Ross (1748–1823) is one of the few Quaker craftsmen to whom forms like those just discussed can be firmly documented. Jonathan’s choice of trade and his grandfather’s pioneer presence at Opequon cement the Rosses as the first multigenerational furniture making family in Frederick County and perhaps the entire northern Shenandoah Valley. Jonathan Ross was born in 1748 within months of the epidemic raging through the Opequon-Hopewell community. The epidemic claimed his grandfather Alexander and his father John Ross within weeks of each other. This left Jonathan to be raised solely by his widowed mother Lydia Hollingsworth Ross, until she remarried to the same William Jolliffe Jr. mentioned earlier in 1750. Lydia died in 1759, leaving Jonathan to live in the Jolliffe household at the Red House. As William Jolliffe’s stepson, Jonathan Ross did not stand to inherit land according to English primogeniture laws; it instead went to Jolliffe’s direct sons John and Edmund in his 1770 will. Jolliffe allotted Ross fifteen pounds sterling in the will, but faced with few prospects as a farmer, the latter pursued a trade.[59]

Ross probably apprenticed to a Quaker carpenter or joiner in the early 1760s. The most likely candidate for Ross’s master was his step-uncle, joiner Abel Walker (1734/5–1823). Abel was the brother of William Jolliffe’s second wife Elizabeth Walker, whom Jolliffe married in 1761.[60] Walker was also connected to Ross in other ways. His brother Mordecai Walker married Arthur Barrett’s granddaughter Rachel in 1758, tightening the knot of the Ross-Barrett-Walker lines. When Ross proposed to marry Martha Brown in 1780, Hopewell elders charged both Abel and Mordecai Walker to make the necessary arrangements.[61] Abel lived approximately two miles northeast of Hopewell Meeting House close to Clear Brook; his home appears on Thomas Fisher’s 1777 map of the Winchester vicinity (Figure 49).

At the sale of Walker’s estate after his death in 1823, executors sold numerous tools used in making joined furniture forms:[62]

|

Brace and bitts |

1 saw mill saw |

|

2 lots of chisels |

2 planes |

|

1 saw and set |

Fore planes |

|

1 lot of turning tools |

1 rabbet plane |

|

Coopers tools |

1 rounding plane |

|

1 iron square |

1 quarter-inch auger |

|

1 frame saw |

1 inch auger |

|

1 half-inch auger |

1 inch-and-a-half auger |

|

1 square and gauge |

1 draw knife |

|

1 turning lathe |

1 glue pot |

Though perhaps less likely, several other Quaker craftsmen worked in the Hopewell area in the 1760s to whom Ross might have apprenticed, including: John Adams, Thomas Babb, Samuel Britton, Edward Dodd, Josiah Ridg(e)way, Simon (or Simeon) Taylor, and John Wright.[63]

Little else is known about Ross until the late 1760s. In October 1767, at nineteen or twenty years old, he petitioned Hopewell for a certificate to East Nottingham Monthly Meeting in Chester County.[64] Investigating and preparing his certificate took the better part of a year; Nottingham Friends did not receive Ross until October 1768.[65] Upon moving to Pennsylvania, Ross probably stayed with his aunt Lydia Ross and her husband John Day(e) Sr. (ca.1705–1775) at their home Hebron’s Gift in present-day Cecil County, Maryland.[66] Ross witnessed Day’s will written in May 1774, where Day bequeathed to his second son Joseph his “land and tanyard in Virginia bought of Stephen Ross.”[67]

Ross worked in an unidentified Nottingham-area cabinet shop over the next seven years. He was probably over twenty-one years old at the time and capable of negotiating wages, thus indenture records do not appear in Nottingham Meeting minutes. He returned to Virginia in late 1775 or early 1776. Accompanying Ross were two other Friends, Edward White and clockmaker Goldsmith Chandlee. Chandlee was coming to Virginia for the first time. Nottingham records noted that all three Friends were, “young, Single Men,” to be recommended to Hopewell so long as “nothing appears to Obstruct.”[68] While Chandlee settled in or near Stephensburg, Ross’s presence in Hopewell Meeting minutes over the next few years suggests he lived somewhere near the meeting house. His surviving pieces further illustrate the imprint of Chester County and particularly Nottingham area styles onto Virginia-made furniture.

Ross’s earliest dateable piece of furniture is a walnut tall case clock with works by Chandlee (Figure 50). In addition to Chandlee’s signature engraved onto a brass boss set into the dial (Figure 51), Ross signed and dated the case multiple times. The signatures appear on either side of the topmost board of the hood. On the upper side of the board, heavily oxidized, is the inscription: “March the 2 Day 1787 / Made by Jonathan Ross / 1787” (Figure 52). Similarly, the signatures underneath the top read “March the 2 Day 1787 / Jonathan / Ross 1787” in red crayon. This combination is unusual in that Ross identified the name of the month rather than using the number assigned by the Quaker calendar, as is commonly found on Quaker-made pieces in Pennsylvania.[69]

The clock appears in an early 1900s interior photograph of Circle Hill, the Pidgeon family house in present-day Clarke County, Virginia (Figures 53 and 54). Circle Hill sits several miles northeast of Hopewell near the present-day Jefferson County, West Virginia, border. Family history maintains that the clock’s first owner was Goldsmith Chandlee’s cousin George Chandlee (1753–1823) of Frederick County, Maryland and Burlington, New Jersey. In this scenario, George Chandlee’s granddaughter Sarah Chandlee brought the clock to Circle Hill upon her 1850 marriage to Samuel Lukens Pidgeon (1817–1902). While possible, more likely the clock originated with someone closer to the Hopewell community, like Samuel’s parents Isaac Pidgeon (1769–1823) and Elizabeth Walker (1773–1825).[70] Isaac and Elizabeth married in 1812 and purchased Circle Hill that same year. Elizabeth was the daughter of Ross’s probable master and step-uncle Abel Walker. Abel did own an eight-day clock at his death in 1823, but Elizabeth’s brother Edward purchased it at their father’s estate sale for $30.00. To date, the clock’s original owner(s) remains uncertain.

The case of the Ross-Chandlee clock has a number of other distinctive features (Figures 55 through 57), including:

-

• Spiral or pinwheel-cut, applied rosettes

-

• A carved keystone appliqué

-

• Arched scrolls that flare slightly upwards at the ends

-

• Smooth, unfluted, applied quarter columns

-

• A rectangular applied panel in the base

-

• Short, squat ogee bracket feet

Similar features appear on a clock published in Edward E. Chandlee’s 1943 Six Quaker Clockmakers with works by Goldsmith Chandlee’s father Benjamin (Figures 58 and 59). The case has all of the features of the Frederick County example with the additions of hollow corners on the applied base panel, brass capitals and plinths for the hood colonnettes, and a single, surviving ball finial with a spire tip above the tympanum.[71] This clock could represent Ross’s work while still in Chester County or an example from the shop in which he worked while there. The owner at the time of publication, Mrs. Wilson P. Foss, III, was a Chandlee descendent, suggesting the clock was made for someone in the family.[72]

Together the two cases are indicative of larger traditions common to southern Chester County and specifically the circle of joiner Jacob Brown (1746–1802) of West Nottingham (Figure 60).[73] Cases attributed to Brown have similar—if more complex—features and also provide evidence for those missing on the Ross examples. The beat finials on the corners of several Brown cases commonly stand on fluted plinths. Those that adorned the clock case in the collection of the Museum of Shenandoah Valley (Fig. 50) have been lost, but glue residue illustrates where they once were.

How Jacob Brown and Jonathan Ross were connected is not presently known, if they were at all. Brown worked roughly in the same period as Ross, suggesting they were contemporaries and not master and journeyman. The two craftsmen might have trained in the same, unidentified shop or an allied one in the Nottingham area. An interesting connection to the Brown family comes with Ross’s 1780 marriage to Martha Brown of Hopewell.[74] Martha was the daughter of William and Martha Brown, both originally of Birmingham Monthly Meeting in eastern Chester County. The Brown family migrated first to Fairfax Meeting in Loudoun County, Virginia in May 1768, before transferring to Hopewell in May 1776.[75]

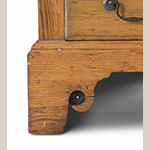

Jonathan Ross requested a transfer from Hopewell to Crooked Run Meeting south of Stephensburg in May and September 1795, which helps account for his two other surviving pieces of furniture.[76] The first is a walnut chest with a two-over-four graduated drawer configuration and oval-plate brasses attributed to Ross based on its origins and similarities in construction (Figure 61). The chest descended in the family of Thomas Steel (1750–1834), a non-Quaker Ulsterman who came to American by 1765.[77] Once in the Valley, Steel settled along the North Branch of Crooked Run (also known as Stephens Run), less than four miles from the Quaker meeting of the same name. The complex molded top closely resembles moldings found on the signed clock. The chest also has smooth quarter columns, which are bounded by simple capitals and bases (Figure 62). Unlike the clock, the chest has ogee bracket feet with the slight hint of spurs (Figure 63).

The second piece is a tall chest of drawers signed and dated by Ross (Figures 64 and 65). The chest is inscribed: “Made / By Jonathan Ross 1805 / October [illegible] / 1805”. MESDA researchers documented its ownership to “a Dr. Hudson” of Luray, Virginia, likely Dr. William Rutledge Hudson who died in July 1916.[78] Luray is approximately thirty miles southwest of the Crooked Run Meeting site along the South Branch of the Shenandoah River. Unlike the smooth quarter columns found on both the clock and the bureau, the tall chest has simple chamfered corners terminating in lamb’s tongues.

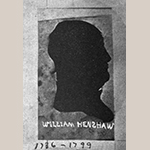

While possibly a tall chest missing its base molding and original feet, the case might also be the upper section of a chest-on-frame, a form common to the area of southeastern Pennsylvania in which Ross worked (Figure 66). At least one other chest-on-frame, missing its original trifid feet, can be documented to the Lower Shenandoah Valley (Figure 67).[79] MESDA field researchers documented its origins at Springhill, the Henshaw family homestead in present-day Berkeley County, West Virginia (Figure 68).

Captain William Henshaw (1736–1799) built Springhill near Mill Creek around 1776 or 1777 along with several nearby grist mills (Figures 69 and 70). By the Revolutionary period multiple family members had converted to Presbyterianism, but Quaker records from various sources reveal that the Henshaws (also spelled Hancher, Handcher, and Hanshaw) were formerly Friends. Nicholas Henshaw (1705–1777) was the first to come to the Shenandoah Valley and settled on Mill Creek. He requested a certificate from Nottingham Monthly Meeting to Hopewell in July 1739.[80] Within a couple of decades, numerous family members were expelled from the meeting. The above-mentioned William Henshaw, for example, was accused in April 1762 of assisting, “his Sisters marrying out from among friends and has been guilty of Dancing at Several wedings [sic].”[81] He was read out of meeting in August of the same year for failing “to Condemn his outgoings” despite counsel from several Friends.[82]

William Henshaw served during both Lord Dunmore’s War and the Revolutionary War, against the Quaker doctrine of pacifism, but he continued to associate with his Quaker neighbors until his death. He witnessed and signed the marriage certificates of at least three newlywed couples at Hopewell over a near twenty-year period, including John Wright and Phebe Barrett in 1773, Stephen Thatcher and Ruth Forknere in 1780, and David Griffeth and Ruth Butterfield in 1792.[83] Stephen Thatcher and Ruth Forknere also belonged to Middle (or Mill) Creek Meeting, likely the Henshaw’s weekly meeting before disownment.

Henshaw probably built Springhill after the death of his father Nicholas, at which time he also furnished it.[84] At William Henshaw’s death in 1799, he owned a variety of furniture forms, including “1 Walnut Chest” valued at 9s and “1 Chest of Drawers” appraised dually at $16 and £4.16. Either listing could represent the chest-on-frame at this late date.[85] The maker of the chest-on-frame could have been someone closely related to William Henshaw. Later generations of Henshaws are documented as furniture makers and Henshaw’s own estate inventory lists a smattering of woodworking tools:[86]

|

2 screw augers |

1 drawing knife |

|

6 augers |

1 old axe |

|

4 chisels |

1 broad axe and hand saw |

|

1 cross cut saw |

1 hand saw and broad ax |

|

1 foot adze |

|

If not a member of his immediate family, William Henshaw might have turned to other makers working along Mill Creek or in nearby Gerrardstown. An intriguing possibility lies with the Anderson family, Chester County transplants with at least one documented early woodworker.[87] Regardless of its maker, the Henshaw-family chest-on-frame provides additional evidence for the often Quaker-made form in the Lower Shenandoah Valley.

Jonathan Ross Disowned

Like many Friends after the Revolution, Jonathan Ross’s story ended outside of the Society that was such an important part of his family legacy. In April 1809, Ross presented a certificate of removal from Hopewell to Alexandria Monthly Meeting in Alexandria, Virginia.[88] For the first few years, at least, he participated in some of the Society’s benevolent principles, such as persuading Friends to free their enslaved servants. In March 1808, for example, Ross and Hopewell member William Jolliffe (probably of some relation to Ross’s stepfather William Jolliffe Jr.) convinced Friend Andrew Scholfield to release a slave woman named Clara from bondage.[89]

Within a few years, however, Ross ran afoul of Quaker doctrine. In October 1813, Alexandria elders investigated the joiner for violating testimony “by appearing in the ranks for the performance of military duty and also furnishing a substitute upon a late requisition from the Government for the performance of military duties.”[90] Ross was likely called up for militia service as part of the War of 1812. The inquiry into Ross’s actions carried through the end of year, finally resulting in the following judgment on 23 December 1813:

Whereas Jonathan Ross who has had a birth and education among Friends has violated our testimony against war by furnishing a substitute upon a late military requisition from the government and he having been tenderly but unavailingly treated and waited with in order to convince him of the necessity of supporting that testimony in favor of peaceable principles—We hereby disown him from having a right of membership in the society, sincerely desiring that he may yet by yielding obedience to those things which belong to his peace become qualified to be reinstated.[91]

Ross did not stay in Virginia after his disownment. He moved to Champaign County, Ohio, and might be the same Jonathan Ross for whom an estate bond was entered in September 1815.[92] His gravestone in Christiansburg, Ohio, claims a later date for his death: 28 May 1832 (Figure 71).[93] Unfortunately, there is no known furniture from Ross’s time in Alexandria or Ohio. However, a clock with a case made around 1818 for Quaker silversmith and clockmaker Mordecai Miller of Alexandria in the Nottingham style (complete with carved spiral rosettes similar to the signed 1787 clock) might be evidence of his influence there (Figures 72 and 73).

In being disowned, Ross fell subject to the Philadelphia and Baltimore Yearly Meetings’s early nineteenth-century attempts to better codify and enforce types of misconduct. His misstep of military participation of any kind was high on the list of offenses, but these also included gambling, swearing, obsessive drinking and more benign activities like attending a wedding as befell the Henshaws. Ross was only one of several Quaker furniture makers in this article whose differing opinions about worldliness and the meeting’s role in personal life led to a break from the Society. These same differences, coupled with theological shifts, rocked the Quaker world in 1827 and 1828.

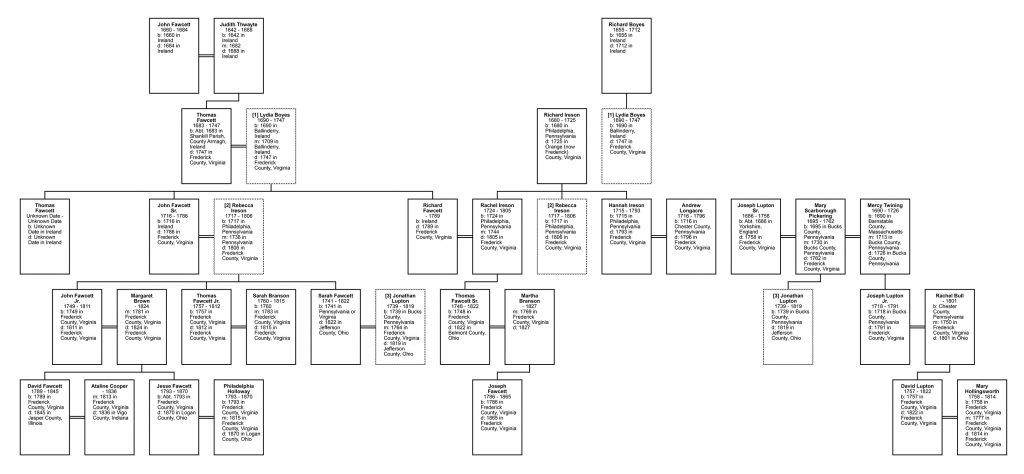

Fawcett Family—First and Second Generations

While the Rosses represent the earliest multi-generational Quaker furniture tradition in Frederick County, they were not the largest. That designation belongs to another group: the Scotch-Irish Fawcett family (see Appendix B for the Fawcett family genealogy). First settling along Cedar Creek in the southwestern part of the county, the Fawcetts produced at least four—and possibly more—generations of furniture makers and consumers. While the earliest generation seems to have focused on turned traditions like chairmaking, subsequent generations diversified their offerings to also include casework. This diversity of forms makes the Fawcetts an excellent case study for Quaker furniture making in the Lower Shenandoah Valley.

Chairmaker Thomas Fawcett (ca.1683–1747) is the earliest documentable craftsman in the larger network.[94] [95] Fawcett first appears in Irish records as a member of Grange Meeting in County Tyrone in 1708. In June of that year, he married Lydia Boyes of Ballinderry Meeting at the house of Richard Boyes, either her father or another close family member.[96]

Thomas and Lydia Fawcett presented certificates of removal from Ballinderry to Chester Monthly Meeting in Pennsylvania in November 1736, implying they made the voyage across the Atlantic sometime in the preceding months. The certificate also mentions the couple’s three sons: Thomas (dates unknown), John Sr. (1716–1786), and Richard (d.1789). The latter two became documented woodworkers. For several years after arriving in America, Thomas Fawcett attended Springfield Monthly Meeting in Chester (now Delaware) County. He appeared on tax lists for Springfield Township in 1737, 1739, and 1740. Unfortunately, none of Fawcett’s Pennsylvania work is known at this time.

Thomas led the family’s migration to the Shenandoah Valley, settling there in the spring of 1743 with his wife Lydia and their unmarried son Richard.[97] Their middle son John, his wife Rebecca Ireson, and their two young daughters followed two years later in the spring or summer of 1745.[98] Where exactly the Fawcetts lived upon arriving in Virginia is unknown. Most likely they settled on land near present-day Fawcett Gap at the foot of Little North Mountain in western Frederick County (Figure 74). This land did not formally enter Fawcett family hands until the 1750s with a series of patents issued by Thomas, Sixth Lord Fairfax, but within a decade it had become an important local juncture. The east-west road through Fawcett Gap connected Quaker Isaac Zane’s first incarnation of Marlboro Furnace on the western side of Little North Mountain to wider road networks and customers. When Zane relocated his enterprise east of Little North Mountain in search of more malleable ore in the late 1760s and early 1770s, the north-south road once again ran through Fawcett family lands. The Fawcetts benefited greatly from Zane’s nearby presence. The constant need to bring in raw materials and transport out finished products like iron pigs and stove plates ensured the roads at Fawcett Gap were some of the best in the county before the Revolution.[99]

Thomas Fawcett died in early 1747, only a few years after he brought his family to Virginia and before they acquired clear title to their land. Fawcett’s wearing apparel and livestock made up the majority of his estate, but he also owned a variety of tools used in the furniture trade:[100]

|

A grindstone |

A hand saw |

|

Two broad axes |

Turning tools |

|

A drawing knife |

One carpenter adze and other small tools |

|

Two falling axes |

Walnut planks |

|

Four augers |

A crosscut saw |

Only one object possibly by Thomas Fawcett survives, but it makes the point that Quakers occasionally, or perhaps frequently, made furniture for non-Friends. In June 1746, the Frederick County Court appointed clerk Colonel James Wood “to Agree with Thomas Fossett for One Dozen of Chairs for the Use of the Court.”[101] The Court settled with Fawcett in November for the chairs, valued at 2s.3 each for a total of £1.7.[102] An armchair in the collection of the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley has a history of descent in the Wood family at Glen Burnie and might be one of these original court commissions (Figure 75).[103]

The Wood family armchair reflects a craftsman who brought Chester County styles to the Virginia Backcountry and adapted them to suit his preferences and those of his clients. The chair has seven, slightly graduated slats, more than the five or six commonly found on Pennsylvania examples.[104] All attention is drawn to the front of the chair. The front posts are interrupted with bulbous turnings topped by a baluster and ball tenoned into the armrest returns. The chair’s most impressive decorative feature is the boldly turned front stretcher with arrow-ends, baluster turnings, and a central compressed disk. A good comparison of these features to Chester County antecedents comes with a rush-bottom couch with a history of descent in the Darlington family (Figure 76). Features like the graduated slats, turned front stretcher, and ball finials saw continued use in southern Frederick County chairs into the nineteenth century, perhaps evidence of the Fawcett’s influence on local traditions. A side chair with a history in the Steele family of Locust Hill in Stephens City, where later generations of the Fawcetts settled, is an excellent extant example of this stimulus (Figure 77). Other ladderback chairs appear in local historic photographs, including two depicting the women of Hopewell-Centre Meeting participating in a play to benefit the local Civic League Milk Fund in the 1930s (Figures 78 and 79). Scattered throughout the scene are chairs presumably brought by the Quaker women from their homes.

Some of the Wood family chair’s original features are now gone. The rush-bottom seat is a late nineteenth or twentieth century replacement, speaking to the chair’s continued use and value to the Wood family. A void between the lowermost slat and the seat suggest the chair originally had a squab or cushion. The chair has traces of green or perhaps a light blue paint, best seen on the back of the slats, in the joints, and on the spool just below the ball finial (Figure 80). Chairmakers frequently painted chairs in similar colors in the period, with green being the most common. Paint decoration was particularly important for chairs of contrasting woods like the maple and ash (or possibly hickory) in this example.[105]

The chair illustrated in Fig. 75 could also represent the work of Thomas’s son Richard Fawcett (d.1789). One of Thomas’s two sons to enter the furniture trade, Richard presumably learned chairmaking from his father either before they moved from Ireland or while in Pennsylvania.[106] Other evidence points towards a proficiency in turning. In May 1750, the wardens of Frederick Parish bound orphan John Henry to Richard “Fosset” to learn “the art of a wheel wright” and receive schooling for two years.[107] Fawcett applied his turning skills over a ten-year period from 1743 to 1753 making and repairing chairs for the James Wood family of Glen Burnie. The documentation for this relationship is spread across a couple of sources. A February 1743 receipt signed by “Richard Fosset” in James Wood’s loose papers at the Stewart Bell Jr. Archives in Winchester accounts for fourteens chairs, for which the chairmaker charged £3.3.4 (Figure 81).[108] Another receipt in the loose papers from two years later issued by Fosset and signed with his mark included thirty shillings for unidentified “work done” (Figure 82).[109]

James Wood’s surviving ledger book in the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley collection records two more instances in which Richard Fawcett made or repaired chairs for the Wood family, first in February 1749 or 1750 and the second in April 1753 (Figures 83 and 84). In the first instance, Fawcett made “4 Chairs” valued at 10s and “a Childs Chair” for 2s.6. The chairmaker also bottomed an unknown number of chairs for 6s.11, an important note that proves the Fawcetts made chairs that required rush or splint seats like the surviving Wood example.[110] The second order in 1753 closely resembles James Wood’s agreement with Richard’s father several years before. On 23 April, Wood noted “By a doz of Chairs @ 5. cm” for a total of £3 and “bottoming and manding [sic] Chairs” at 8s.[111]

Two other objects with Fawcett associations survive from the first or second generations. First is a cradle which descended directly in Richard Fawcett’s line and was still in the family until recently acquired by the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley (Figure 85). While missing its rockers, each of the four corner posts bear ball finials (Figure 86) very similar to those on the Wood family great chair (Fig. 80). Most likely, Richard made the cradle for one of his six children. All six children were born between 1745 and 1761, which fit comfortably with the cradle’s age and style. Alternatively, Richard’s brother carpenter/joiner John Fawcett Sr. could have made the cradle as a gift for the family.

The second object, a table made entirely of walnut, currently resides at Hopewell Monthly Meeting but is not original to the building (Figure 87). The table’s legs are comprised of roughly turned balusters over compressed balls, separated from the feet by elongated blocks (Figure 88). With the exception of the tulip feet, the overall form closely resembles examples made in Chester County and southeastern Pennsylvania around the middle of the eighteenth century (Figure 89). The original top is secured to the frame with wooden pegs, but was reinforced with nails early in the table’s life. Despite the attempts at reinforcement, part of the top has broken off on one side and is now gone.

Thought to be original to the meeting house by historian John Walter Wayland in 1936, in fact the table was a gift to Hopewell sometime in the early twentieth century by Sarah Jane “Sallie” Lupton Jolliffe (1848–1925) (Figure 90).[112] A circa 1960 meeting newsletter recorded the gift:

The walnut table, always in the same place on the south-east side, came from the Sallie Lupton Jolliffe household. It was loaned to the meeting years ago, and has been in constant use, and much admired by “antique enthusiasts.”[113]

MESDA field researchers recorded a similar provenance in 1980, with the addition that the table descended from the Lupton side of Sallie’s family on Apple Pie Ridge. The approximate age of the table and Sallie Lupton’s direct line leads to two possible early owners: Joseph Lupton Sr. (ca.1686–1758) and/or his son and namesake, Joseph Lupton Jr. (1718–1791). The elder Joseph was the progenitor of the family in the Shenandoah Valley, English Quakers who settled first in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Joseph and his family, including his young son, requested a certificate of removal from Buckingham Monthly Meeting to Virginia in April 1741.[114]

The Luptons initially acquired land west of Winchester near present-day Round Hill, approximately six miles from Fawcett Gap (Figure 91). Subsequent generations purchased and/or inherited land on Apple Pie Ridge north of Winchester and closer to Hopewell, but for decades the Luptons and Fawcetts lived in close proximity to each other. A good example of their interactions comes with the death of Joseph Lupton Sr. in 1758, who was buried at Hopewell in a simple grave as befit Society expectation. Chosen as witnesses to his will were brothers John and Richard Fawcett and their brother-in-law Andrew Longacre, whose status as a craftsman is unknown.[115] Like with the Ross and Hollingsworth families, the Luptons and Fawcetts eventually cemented their relationship with a marriage. In 1764, Sarah Fawcett (1741–1822), the daughter of John and Rebecca Fawcett and the granddaughter of Thomas the immigrant, married Jonathan Lupton (1739–1819), the son of Joseph Lupton Sr. and his second wife Mary Scarborough Pickering at Fawcett Gap.[116] The close neighborly and kinship ties suggest the walnut table could have been made by either John or Richard Fawcett sometime before Joseph Sr.’s death in 1758 or even slightly thereafter for his son.[117]

Friends Over the Mountain—Quakers in Loudoun County

A stylistically similar table from another area of Quaker settlement in Virginia—Loudoun County, which adjoined Frederick in the period—helps to provide context for forms brought down the Great Wagon Road from Pennsylvania (Figure 92). Unlike the all-walnut Lupton table (Fig. 87), this second table is a mix of two different softwoods. The majority of the table including the top, side rails, and turned legs are poplar (Figure 93). The stretchers making up the base are yellow pine, with a single bead running along the top. While the table currently is at Goose Creek Meeting in Purcellville, Virginia, a 1929 label formerly pasted underneath the original top confirms its origins at the Waterford Monthly Meeting in Loudoun County (Figure 94) and also offers some of its later history:

This table is one of a pair used by the Clerks of Fairfax Monthly Meeting. This Meeting was established at Waterford in 1744 and tables gotten about that time. One was used by the men, the other in women’s Meeting, the business Meetings held separately. Fairfax Monthly Meeting was discontinued in 1929 and this table placed with our friend Chas. [Charles] J. Walker at his home in Paeonian Springs to be cared for by him. The table served various purposes, was much in use during the Civil War (1861–65) as a card table by the Confederate troops occupying the Meeting House much of the time. The other table disappeared during the war.[118]

The note’s introductory statements reference the settlement of the Waterford area in Loudoun (then Fairfax) County by Bucks County, Pennsylvania Quakers in the 1730s and 1740s. Like with Ross at Hopewell, the Waterford settlement had a leading figure in Amos Janney (d.1747). Janney purchased 400 acres along the south fork of Catoctin Creek from Thomas Fairfax, 6th Baron of Cameron in 1732. By the early 1740s, he had constructed both a gristmill and sawmill on the creek’s banks. In 1741, Janney built a log meeting house on his land, dubbed Fairfax Meeting as Waterford was still a part of Fairfax County.[119] Fairfax Meeting fell under Hopewell Monthly Meeting’s jurisdiction until 1744.

Numerous families and Friends from Pennsylvania and New Jersey followed Amos Janney to Waterford in the following years. Among them was Amos’s younger brother William Janney (1710–1790), identified in several records as a joiner. Though William was just a few years younger than Amos, evidence suggests he did not move to Virginia until the early 1740s. In fact, he was in Bucks County at least as late as October 1739, where he married Elizabeth Moon at Falls Monthly Meeting near the falls of the Delaware River.[120]

The earliest Waterford record for the craftsman is a May 1744 land purchase mentioning William Janney “of the County aforesaid Joyner.”[121] He purchased 165 acres from a survey laid out by his brother Amos for an unknown price. While William was probably in Waterford as early as 1744, he did not officially request a removal from Bucks County to Virginia until 1758. In December of that year, Falls Monthly meeting minutes mention: “being informed that William Janney some time since went from hence and is now in Virginia. But as he went without giving notice to the Meeting or requesting a Certificate,” it fell to Bucks County Friends to, “prepare such Certificate as we can give, in order to it being sent to Friends there.”[122] William lived and worked in Loudoun County until his death in 1790.

William Janney is one of two likely candidates to have made the Waterford Meeting table, the other being Chester County carpenter John Mead. Mead moved with his family to the Waterford settlement in the early 1730s before picking up again around 1746 bound for Bedford County, Virginia.[123] Mead’s short timetable in the area and William Janney’s relationship to his brother and meeting-founder Amos tilt the attribution of the meeting table in William’s favor. When analyzed side by side, the Fawcett and Janney tables together make the point that in this early period of settlement there was little visual difference in Quaker forms intended for household use versus those used in meetings spaces. This point becomes even more concrete with the realization that many private homes also served as weekly meeting places.

Third Generation—John Fawcett Jr. (1749–1811) and Thomas Fawcett Jr. (1757–1812)

Furniture making traditions continued in the third generation of the Fawcett family with John Fawcett Sr.’s oldest sons: John Fawcett Jr. (1749–1811) and Thomas Fawcett Jr. (1757–1812). The latter bore the “Sr.” suffix to differentiate himself from a first cousin by the same name.[124] This generation was the first to be born in the Shenandoah Valley. Records do not survive to illustrate the brothers’ training, but they likely trained with their father and and/or their uncle Richard. The brothers also expanded their family network by marrying into families outside of the Fawcett Gap area. John Fawcett married Margaret Brown in 1781, whose family migrated from Chester County early on.[125] Thomas married Sarah Branson two years later in 1783. Sarah’s family were Friends originating from Springfield Township in Burlington County, New Jersey.[126]

The two brothers probably worked in partnership for much of their lives and died within a year of each other. Their estates offer the most complete look at the furniture making trade within the larger family. John Fawcett Jr.’s 1812 inventory, taken several months after he died, included the following furniture making tools:[127]

|

6 axes |

1 pair of compasses |

|

1 iron wedge |

3 lots of tools for joiners |

|

2 stocks of walnut boards |

2 broad axes |

|

1 grindstone bench and axe trees |

1 hand axe |

|

3 saws |

1 lot of cooper’s tools |

|

3 augers, chisel, and gouge |

1 cutting box and whetstone |

Thomas Fawcett Jr.’s estate was not recorded until over a decade after his death in late 1812 or early 1813. It entered public record on 31 May 1824, and included:[128]

|

1 cutting box and knife |

145 feet of oak plank |

|

3 old axes |

100 feet of scantling |

|

3,000 cooper’s staves |

1 grindstone |

|

1 set of cooper’s tools |

1 broad axe |

|

1 parcel of planes |

1 hand axe |

|

1 parcel of chisels and gouges |

1 whetstone |

|

2 braces & bitts |

6 augers |

|

6 files |

1 foot adze |

|

1 glue pot |

1 set turner’s tools and lathe |

|

Gimlets |

Paint brushes, jugs, and pigments |

|

2 saws |

1 shaving horse and clamps |

|

3 drawing knives |

|

The vendue of Thomas Fawcett’s estate was entered into county records the same day, recording several lots that were likely broken down and sold individually from the above groupings:

|

1 pruning chisel |

1 square and rule |

|

1 hand saw |

1 lot files and rasps |

|

1 tenant [tenon] saw |

2 “oyl” jugs [possibly for varnish] |

The brothers’ combined estates also list a wide variety of furniture forms that they might have made for clients and neighbors:

|

1 cupboard |

1 table |

|

1 chest |

1 clothes press |

|

1 case of drawers |

1 knife box |

|

2 kitchen tables |

1 stand |

|

1 kitchen cupboard |

1 falling leaf table |

|

1 arm chair |

1 kitchen dresser |

|

6 Windsor chairs |

1 small chest |

|

6 common chairs |

1 clock |

|

1 trundle bed |

1 tea table |

|

1 looking glass |

1 case and stand |

The clothes press listed valued at $8.00 in John’s inventory and the clock listed at $75.00 in Thomas’s are particularly important. One or both of the brothers probably made similar forms for their first cousin, Thomas Fawcett Sr. (1748–1822), son of Richard Fawcett and grandson of progenitor Thomas Fawcett. Around the third-quarter of the eighteenth century, Thomas Sr. inherited a tract of land east of the Mount Pleasant Meeting site, part of the original grant progenitor Thomas Fawcett acquired from Thomas, Lord Fairfax in the early 1750s. He built a stone dwelling just below the mouth of Fawcett Gap around 1797, which still stands today (Figure 95).[129] John Fawcett Jr. and Thomas Fawcett Jr. owned the two tracts directly east of the new house, and Thomas Sr. likely turned to his cousins to furnish it.[130] Two pieces possibly made for the 1797 house survive: a clothes press and a tall case clock (Figures 96, 97, and 98). Both pieces are of black walnut and are in private collections. They also exhibit mortise and tenon construction secured with wooden pegs, typical more of a carpenter or joiner’s work rather than that of a cabinetmaker.

In October 1814, Thomas Fawcett Sr. and his family moved to Plainfield, Ohio. He died several years later in Richland, Belmont County, in 1822. He directed that his will be settled in “a friendly manner” and provided for his wife during her lifetime. To his son and executor Joseph Fawcett he bequeathed one quarter of his lands in Ohio and “all my moveable property now on my plantation in the State of Virginia,” presumably with the large, difficult to move furniture pieces like the clothes press and clock still in the house.[131] Whether Joseph was living in Ohio or Virginia at this time is unknown, but at his death in 1865 he was clearly living on the plantation left to him in Frederick County. Both the clock and press descended in Joseph’s direct line into the twentieth century.[132] The clock remains in family hands today.

No other pieces by John Fawcett Jr. or Thomas Fawcett Jr. are currently known, but the latter’s will suggests he made other forms for family members. In his will probated January 1813, Thomas Fawcett Jr. made the following bequest [emphasis added]:

I give and bequeath unto my daughter Lydia the second choice of a bed and bedstead, bolster and pillows with their cases, one pair of sheets, one pair of blankets, two coverlets to be estimated at forty dollars, one case of drawers called hers, twelve dollars, her saddle, and bridle twelve dollars, and six chair not to be charged, making in all $63, to her, her heirs, and assigns forever.[133]

The designation “called hers” might imply that Fawcett made the chest for his oldest daughter. Based on the twelve-dollar value and Fawcett’s description, the piece was probably a tall chest of drawers or chest-on-frame rather than a smaller, four-drawer bureau.

Fourth Generation—Fawcetts Leave the Society of Friends

Like with Jonathan Ross, the men of Lydia’s generation continued the woodworking traditions of their forebears. At Thomas Jr.’s 1824 estate sale, his son John and nephews Isaac (b.1782) and David Fawcett (1789–1845) purchased many of the tools, scantling, and plank. David in particular purchased his uncle’s turning lathe and multiple chisels.[134] Although he did not purchase any of his uncle’s tools at the estate sale, other local records identify David’s younger brother Jesse as some type of woodworker, perhaps either a carpenter or cooper. In June 1820, Jesse found himself in debt to his older brother Nathan in the amount of $212.00 plus interest. To secure the debt, Jesse placed multiple tools and other personal effects in trust with another brother, Elijah Fawcett (b.1784), including one axe, one lathing axe, one handsaw, two augers, three chisels, one drawing knife, a gimblet, one barrel of vinegar (possibly used as an ingredient for finish), and one lot of pine plank.[135]

David Fawcett’s purchase of the turning lathe and chisels suggests he intended to continue the turned chair tradition established by his great-grandfather Thomas. Unfortunately, no chairs signed by or attributable to David are known at this time. There was, however, a distinct Delaware Valley-style turned chairmaking tradition in southern Frederick County throughout the nineteenth century. The center of this tradition was likely Stephensburg, where David owned land by 1820 and where the greatest number of extant examples have histories (Figures 99, 100, and 101).[136] Most of the chairs have some variation of a ball finial topped by a cap or boss. Examples have been found with balls that are fully round, elongated, and heavily compressed (Figures 102 and 103). The high chair illustrated in Fig. 101 does not retain its family provenance but was recovered in the Winchester area and has pine armrests that are undercut in the Philadelphia manner (Figure 104).

The earliest chair from this group (Figure 105) descended in the same Steele family as the white-painted ladderback example mentioned earlier (Fig. 77). Known to generations of the family as the “Judgement Chair,” tradition claims that Mager Steele Sr. (1792–1863), son of Thomas Steel mentioned earlier, used this chair in his official capacity as a Justice of the Peace for Frederick County from 1837 until 1862. Most likely, the chair predates its use in official matters and like the Wood family armchair began life as a household object, albeit one reserved for the head of the family. Like the Wood family chair, the large void between the seat and armrests suggests it once had a squab. The Judgement Chair of all the chairs in this group most closely adheres to Delaware Valley examples, with turned front stretchers, graduated slats, and shaped armrests. It also has the most fully rounded finial of the group, slightly compressed with a well-worn cap on top (Figure 106).

A flywhisk chair descended in the Fawcett family in the same line as the tall case clock and the clothes press (Figure 107). This chair has the most dramatic departure in terms of the finial. The ball finial has been compressed to an almost mushroom shape with a wide cap on top (Figure 108). It began life as a side chair; the yellow pine foot pedal, vertical member, and swing arm are clearly later additions. In fact, the front of the chair once had an upper stretcher that was removed and the mortises plugged to make room for the mechanism.[137] While difficult to date stylistically, the cut nails with uniform heads holding the mechanism together place the chair sometime between about 1830 and 1860, or perhaps slightly later.

David Fawcett and his wife Adaline Cooper left Virginia for Jasper County, Illinois by the mid-1830s, excluding him as a possible maker of the flywhisk chair. When writing his history of the Shenandoah Valley in the 1833, author Samuel Kercheval noted the early prominence of the Fawcett family, but that numerous branches of the family “have, however, chiefly migrated to the west.”[138] It seems possible, though, that while not the makers of this group, several generations worth of Fawcett chairmakers and wheelwrights cemented a Delaware Valley-style tradition in southern Frederick County that was continued by other craftsmen in the area after they left. Features like the tapered and almost spike-like feet possibly illustrate the influence of other Valley chairmaking families like the Fravels of Woodstock, whose origins are also in the Delaware Valley and whose work has been studied closely by Jeffrey S. Evans.[139]

While adhering to their family’s woodworking traditions, by the mid-1810s the fourth generation of the Fawcett family failed to pursue their trade under the auspices of the Society of Friends. Both Isaac and David Fawcett were reported for failure to attend meetings and for participating in military service in May 1814.[140] Later in the same year, Jesse Fawcett was disowned for failure to attend meetings, attending a wedding contrary to discipline, and serving in the Frederick County militia.[141] Of John Jr. and Rebecca Fawcett’s nine children, only their youngest son Albin remained a Quaker by 1820.[142]

Out-migration to Ohio and the Rise of Winchester

Quaker movement from the mid-Atlantic continued through the early 1800s, but outmigration to areas west of the Appalachians increasingly outpaced the arrival of newcomers in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Hopewell, for example, lost 142 members while gaining only ninety-five in the 1790s. In Quakers Living in the Lion’s Mouth, author A. Glenn Crothers estimates that, combined, the largest meetings in Frederick and Loudoun Counties “lost over three hundred individuals in the decade [1790s], a blow for a population that numbered no more than two thousand in the 1770s.”[143] Fertile, cheap land in the west was once again an incentive to leave, but the continued presence of slavery in Virginia also forced many Friends to reconsider living in a slave state that supported the South’s “peculiar institution.” When places like Ohio opened to white settlement as a slavery-free territory in 1787, Valley Quakers saw it as a place for economic opportunity and freedom of conscience.

Increased disownment of straying Friends likewise affected the Quaker population. As was noted with Jonathan Ross, the Philadelphia and later Baltimore Yearly Meetings demanded more accountability from elders of local meetings after 1775. Historian Jay Worrall estimates Virginia meetings disowned up to twenty percent of their membership between 1763 and 1776.[144] Visiting Quaker minister Joseph Oxley of Norwich, England, attributed the greatest degradation from Friends marrying out of meeting. Visiting Jackson Allen’s meeting house at Quicksburg in central Shenandoah County in 1770, Oxley decried, “it was pretty much of a mixed gathering, and not altogether to satisfaction; we paid sundry visits to particular families of the said meeting, who had mixed themselves in marriage with those of different principles, and in near kindred, much to their hurt.”[145]

Such heavy outmigration coupled with disownment led to the laying down—or discontinuation—of most of the smaller meetings south of Winchester. Crooked Run Meeting, the onetime home to Jonathan Ross, was laid down, or discontinued, by Hopewell Friends in 1807. The remaining members established a preparatory meeting to preserve the congregation, but it too dissolved three years later. The Fawcett family meeting at Mount Pleasant closed two years after Crooked Run in 1809, though a Quaker schoolhouse located nearby saw continued use for part of the 1800s. Family historian Thomas Fawcett noted that “the last Quaker Fawcetts in the valley attended Centre meeting in Winchester.”[146]