In the fall of 1754, Peter Boehler and Andreas Höger traversed a 100,000-acre tract of land in North Carolina that had recently been acquired by the Moravian Church.[1] The Moravians named their Carolina land “Wachovia.” Boehler, a leader in the Moravian Church, and Höger, a skilled map maker who was also Moravian, were tasked to measure Wachovia and produce a map.

Records kept by the Moravians clearly state that Andreas Höger produced a map of Wachovia while he was in North Carolina, but throughout the twentieth century no map had been identified to his hand. In fact, some scholars doubted that the map actually existed. This article reports on the discovery of Höger’s map—an investigation that led to the identification of not one but three maps produced during the short time in 1754 that Peter Boehler and Andreas Höger were in North Carolina. The product of their efforts in Wachovia is remarkable in its thoroughness and the simple beauty of the maps that resulted.

The Höger maps are rare glimpses into and onto the landscape of Wachovia at the very instant that it was being formed on the North Carolina frontier, on the very edge of the movement of settlement toward the west by new settlers hungry for land. And in the course of that movement were a group of people, the Moravians, so unified in a religious identity that they called themselves “The Unity.”[2] Wachovia was a land on the frontier of European settlement, and for those Moravians “Our House,” their first residence in Wachovia, was a simple log cabin with a dirt floor. Near that log cabin was a creek where the Moravians stated they would build a grist mill. The words “Hier is the Mill to be Build” are found on Höger’s map near the creek, a clear record of intention on the landscape.[3]

Autumn 1754

On 10 September 1754, Peter Boehler and Andreas Höger arrived in Wachovia where they joined a small group of Moravian men, themselves only in Wachovia for less than a year, in their newly established settlement of Bethabara.[4] Boehler’s and Höger’s purpose was explicit: to measure the land and to produce the first Moravian map of the Wachovia Tract. In addition, Höger was tasked with delineating a scheme of land division on the landscape of Wachovia that would allow Moravian leadership to sell parts of the tract in order to finance their ownership of the major portions they wished to retain for their own settlement.

Among the small group of Moravian men already settled at Bethabara was Hermanus Loesch, also known as Herman, who had led the initial settlers from Pennsylvania to North Carolina.[5] Loesch was familiar with the Wachovia Tract because he had been with the search party in 1753 when the land was chosen by Moravian Bishop August Spangenberg and surveyed by the Englishman William Churton. Loesch’s skills as a woodsman included hunting, which would play a significant role in identifying the first Moravian map of Wachovia.[6] He was also the one to guide Peter Boehler and Andreas Höger from Pennsylvania to Wachovia and accompanied the men during their two-month endeavor to measure and survey the tract.

Boehler and Höger had completed their work of surveying Wachovia by mid November. They left Bethabara on 18 November 1754 to return to Bethlehem, Pennsylvnia. Of particular significance, the Bethabara diary of 1754 recorded:

One main object of his [Höger’s] visit was to inspect the tract and measure it, and many days were devoted to this, various Brethren being appointed to accompany and assist him. A map was made by Höger, who also made a copy to be retained in the Wachau” [emphasis added].[7]

The words are clear: Höger had made a of copy of his map to be kept by the Moravians in Wachovia.

Despite this evidence, scholars through the years who studied the earliest history of the Moravians in North Carolina could not find or identify the copy of the map left behind by Höger. Some came to believe that this important document did not actually exist.[8] The map that Höger was supposed to have made was not in the Moravian Archives of the Southern Province, where it was believed it should have been deposited. The map was not in the archives, therefore some believed it was either never drawn or did not survive.

Spring 2002

Old Salem Museums & Gardens’s Department of Archaeology conducted research in the spring of 2002 on the southern country congregations of Wachovia, which include Friedberg, Friedland, and Hope. The project also investigated the Adam Spach Rock House, a 1754 Moravian house site and associated land just south of Wachovia. While Spach’s house and land was just outside the Moravian tract, he was an important figure in the early history of the Moravians in North Carolina and instrumental in the creation of the Friedberg Country Congregation. Consequently a search was begun by the author and Old Salem Museums & Gardens researcher Martha Hartley for any maps of the earliest period of Wachovia that might exist and that might shed light on the southern country congregations and the Spach site.

During the course of this search an undated map of Wachovia by an unknown map maker, owned by the Wachovia Historical Society, was examined. The map was on display in Old Salem’s Boys’ School museum building, which had previously housed the collection of the Wachovia Historical Society.[9] Old Salem Museums & Gardens had assumed operation of the Boys’ School as a museum building in the 1950s, as well as curatorial responsibility for the highly significant Wachovia Historical Society collection.

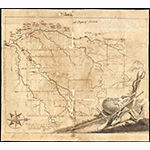

Upon visiting the Boys’ School we verified that the map was indeed on display, framed and under glass, hanging above the mantle of one of the fireplaces of the old building. There was no signature anywhere on the document or on the back of the frame that would identify the draftsman who had created the map. However, even at first glance it was obviously an original draft by a skilled and artistic mapmaker (Figure 1). It had the presentation of a map from antiquity, and a drawing in the lower right corner was a skillful picture of a shot deer (Figure 2). Further investigation of the map was warranted.

The First Höger Map

Examination began with the picture of the shot animal. The deer is lying on its side and the flintlock which had brought the creature down is shown leaning through the many points of the large antler rack and across the body. The shape of the weapon, with its distinctive carved stock, the flintlock, and the length of the barrel seems to represent a gun from the eighteenth century. The wound on the animal, clearly visible on the drawing, shows that it had been killed by a single shot with a large caliber ball.

The weapon is accompanied by a long rod, drawn as though marked in feet. This is a surveyor’s rod, also lying through the antlers and across the body of the animal. However, this surveyor’s rod cleverly provides the scale for the map in inches, and a notation below it states, “Scale of 80 chains to one Inch. (or a Mile).” This drawing is in the typical position and character of an eighteenth-century map cartouche, but, except for the numbers on the surveyor’s rod and the notation below it, the cartouche does not have any text.

The presentation of the map itself is unusual to the point of being unique among maps of Wachovia in that north is to the right rather than in the usual cartographic position to the top of a document. A compass rose pointing to the right is drawn in the lower left-hand corner of the map, opposite the cartouche. The title “Wachovia” appears at the top of the map and indicates that this variation of the name of the land was in use when the map was made.[10] Below that, “36 Degree of Latitude” marks the north-south position of the tract, and vertical text along left edge of the document notes that the land in the presentation lies “between 3 & 4 Degrees of Longitude from Carratuck Inlet.”

The map itself depicts the exterior boundary lines of the Wachovia Tract proper, as well as secondary division internal boundaries. There are also external lots shown against the Wachovia line with the names of individuals listed on these, Nisbet being the most common but Cosart, Weis, and Antes also appear. The topographical formation of the drainage basin of “Gargales Creek” is clearly delineated in three main channels, “South Fork,” “Middle Fork,” and “North Fork,” with a substantial number of tributaries to these forks also depicted. The map clearly records that this drainage basin forms the structure of the tract.

Two houses are shown on the map. At the left, in the south end of the tract between the Middle Fork and the South Fork, a house symbol is labeled “Sweetens Place” with a north-south road running up the middle labeled “Sweetens Road going to our House.” Sweeten was an Irishman the Moravians found on their land without any legal claim to it when they arrived in 1753. He was told that he would have to go elsewhere, and he asked to be allowed to get in a crop he had planted, but he did not stay long.[11]

The depiction of the road bearing his name was drawn through a large segment of the Wachovia Tract that occupies the center of the presentation and is labeled “For the Unity.” This road terminates at the second solitary house symbol on the map at the north end of the tract, labeled simply “Our House” (Figure 3). This house symbol on a tributary of the creek basin is shown just south of another road labeled “Shallow ford Road.” This road crosses into the tract on the northern boundary at a point labeled “Entrance in our Land” and passes out of the tract on its western boundary across “North Fork of Gargales Creek” a short distance to the south of “Black Wallnut Bottom.” Importantly for dating the map, in close association with the symbol labeled “Our House” there is a symbol for a mill site and the notation, “hier is the Mill to be build.”

Convincingly, this last notation indicated that this was the lost Höger map. “Our House” was certainly Bethabara, and the mill at Bethabara was not finished until after 28 November 1755. On 30 November 1755, the Brethren recorded, “we used for the first time bread made from flour ground in our own mill.”[12]

The mapmaker who had drafted this map created it before that mill was built, and that mapmaker would have been Andreas Höger. With that strong supposition in hand, further investigation could be conducted using the animal in the cartouche (Fig. 2). It would have been shot and sketched during Höger’s survey and the Bethabara Diary may have noted that event.

A search of the diary produced the remarkable confirmation of the killing of this animal in 1754 during the exact time Höger was in the field. The Bethabara diarist for 1754 recorded, “During this period we have killed no game except a bear and a deer shot by Br. Herman Loesch on Oct. 29th.”[13] Herman Loesch, the hunter and surveyor’s assistant, while in the field with Höger during the survey, used his skill out in the tract to also secure meat for Bethabara.

The animal shown in the cartouche is actually an eastern elk, or wapiti (now extinct in the American Southeast), which was so similar to the European red deer that they have been argued to be the same species. Consequently, the diarist calling the elk shot by Herman Loesch a “deer” would not be unusual based on what the Moravians were familiar with in Europe.

The result of this examination was that the map, which came to be known to the 2002 researchers as the “Shot Deer” map, is a smooth copy, a finished piece of work, and not a working draft. Therefore it must unquestionably be the map that was made by Höger, “to be retained in the Wachau.” The Wachovia Historical Society’s copious records have not yet revealed the path that the map took to be found in the society’s collection. Unfortunately the history from 1754 until well into the twentieth century remains a mystery.

Another Höger Map

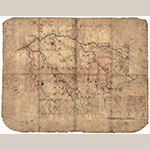

A photograph of another early map of Wachovia was identified in the Old Salem map files at the same time the “Shot Deer” map was being examined in 2002. From the photograph it was determined that this map was a tattered and worn presentation closely related to the “Shot Deer” map but without the cartouche. The notations on the photographic record stated only that it was a map of Wachovia and that it was owned by Miss Sarah Woodard, subsequently Mrs. Sarah Woodard David, a professional preservationist living in Germanton, North Carolina, about fifteen miles north of Winston-Salem.[14] The map’s owner was contacted and she readily agreed to bring it to the museum for examination.

The map, titled “Wachovia in Nord Carolina” (Figure 4), was immediately determined to be another version of the 1754 Höger survey. Again the orientation was with north to the right, with the same details present such as “Sweetens Place,” a road connecting that feature to the single house in the location of Bethabara, and the same numbered lot division scheme.

A significant difference, however, is that in place of the “Shot Deer” cartouche was a listing in Roman numerals that referenced notations on the map and the dates that those places had been surveyed (Figure 5). Below these notations, the scale of the map is again given in chains.

The dates on Roman numerals I and II, which would have been the beginning of the survey, are not clear, but Roman numerals III through XII (with the Arabic numeral “8” curiously substituted for “VIII”) are easily visible, with VI explicitly including the year 1754. The dates are:

I ?

II ?

III 21 Sept

IV 24 Sept

V 25 Sept

VI 1754 26 Sept

VII 31 Oct

8 1 Nov

IX 2 Nov

X 7 Nov

XI 8 Nov

XII 9 Nov

These dates correspond exactly with the period Höger and Boehler were in the Wachovia Tract to measure it and for Höger to produce a map. They also encompass the date that Herman Loesch killed the eastern elk drawn by Höger in the cartouche on the “Shot Deer” map.

Reference to the placement of the Roman numerals on the map itself provides a timeline of how the survey proceeded. Often the section referenced is within a fork of creek channels within the drainage basin, indicating a surveying technique that used creek forks to maintain location within the creek basin and the tract. On this map the creek system is again referred to as Gargales Creek, but with the addition of names placed on smaller branches of the creek basin.

This map, with the series of dates linked to specific places on the map, is clearly a record of the survey while it was in process, providing a unique view of Höger’s surveying methods on the Wachovia Tract at the earliest stages of Moravian occupation of the land. It is also a preparatory record that led to Höger’s smooth copy containing the “Shot Deer” cartouche.

As with the “Shot Deer” map, there was the question of how this second map, now referred to as Höger’s “work map,” came into a private collection in Germanton. In this instance, however, there are some answers. Miss Woodard had received the map as a gift from Ruth Kathleen Petree, a ninety-year-old neighbor in Germanton. Miss Petree’s mother’s maiden name was Blum, a family that has been present in the Moravian communities of Wachovia since colonial times, and the map had come to her through that line. Some genealogical research revealed that one of the Miss Petree’s direct ancestors was John Jacob Blum of Bethabara.[15]

The first documentation of John Jacob Blum in the records of the Moravians in North Carolina comes from 1769 when he assumed management of “the farm,” which at that time was how the Moravians refered to Bethabara. Blum’s management of Bethabara came during a period when it was being replaced by the town of Salem as the administrative center of Wachovia.[16] During and following his time in Bethabara, the Moravians gave John Jacob Blum many responsibilities in the broad Wachovia Tract.[17] Blum’s duties in Wachovia suggest the probability that at the time of his death he was in possession of Höger’s work map of Wachovia and from there it descended through the hands of his family to Miss Petree and then to Sarah Woodard David, whose generosity made it possible for Old Salem to acquire the map in 2018.

And Yet a Third Map

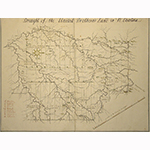

Identification of the two Höger maps led to consideration of the photocopy of a third map deposited in the Old Salem map files. This third map of early Wachovia, titled “Draught of the United Brethren’s Land in N. Carolina” (Figure 6), is held in the Moravian Archives in Herrnhut, Germany, and for years had been discounted by scholars as nothing more than a student’s learning excercise.[18] Despite this previous assessment, a color digital scan of the map was procured and when compared to the others this third map proved to be a near-exact copy of Höger’s “Shot Deer” and work maps.[19]

This map does not have the “Shot Deer” cartouche, and in that respect more closely resembles the work map. While drawn by a hand other than Höger’s, the internal notations at various features correspond to his originals. There are some notable differences however: This presentation includes groupings of low hills at the northwest and the northeast corners and a “New Road” is shown in Lot 10, extending from the north-south central road east through the lot and out of the tract. Regardless, this map was certainly not a student’s copy but unquestionably a version of Höger’s Wachovia map deposited with the Moravian Church’s topmost administrators in Germany. What this map reveals is that Höger’s “draught” was a serious matter of consideration as the European leadership of the Moravian Church sought to determine how they would treat their land on the Carolina frontier.

Conclusion

The first Moravian map of Wachovia is Höger’s tattered work map with its freehand notation of the dates of the survey. The “Shot Deer” map, derived from the work map, was drawn second and left with the Moravians in Bethabara. Höger created this map with a cartouche representing a moment in time significant only to the Brethren in Bethabara: Herman Loesch’s successful hunt on 29 October 1754.[20] And third, the Herrnhut map follows after the information on Höger’s maps arrived in Europe and is an indicator of a broader distribution of that information through the Moravian’s central leadership.

In one sense, the succession of maps produced by the first Moravian surveyor of Wachovia were not successful. They did not fulfill the requirement of distributing land to be sold and land to be retained in a way that met the needs of the Moravians in Wachovia. It would be another twelve years until a final land distribution plan for the Wachovia Tract was approved.

However successful or unsuccesful Andreas Höger’s 1754 mapping of Wachovia may have been, the three surviving maps bring into focus a record of intention on the landscape. They are a statement from the frontier of North Carolina that a people with a long view of the future have come into a new land. Höger is saying, “Here is our land. What shall we do with it?”

Michael O. Hartley is the emeritus archaeologist at Old Salem Museums & Gardens. He may be reached at [email protected].

[1] The actual size of the tract of land acquired by the Moravians was 98,987 acres, but the Wachovial Tract was and is commonly thought of as having 100,000 acres.

[2] The Unitas Fratrum, or Unity of the Brethren, is a church that has its origins in the 1415 martyrdom of the Catholic priest Jan Hus. Hus was a priest from Bohemia, which with the region of Moravia forms the present Czech Republic. He advocated much greater participation in the practices of the church by the laity and for this was burned at the stake for heresy. Hus’s death led to a growing number of followers in Bohemia known as Husites who also wished for the participation he advocated. These followers pressed their demands into the Husite Wars in protest of the control by Rome. Out of these Husites emerged a gentle group in 1457 who established a society called the Brethren of the Law of Christ, which formed the origins of the Unitas Fratrum, or United Brethren. After undergoing the turmoils of the Reformation and the Counter Reformation, refugees from Bohemia and Moravia were given sanctuary on the Saxony estate of Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf and in 1727 formally renewed their ancient church as the Unitas Fratrum. Members of the church are commonly known as “Moravians” in the English-speaking world. Chester S. Davis, Moravians in Europe and America, 1415–1865 (Winston-Salem, NC: Wachovia Historical Society, 2000).

[3] See notations on the map illustrated in Fig. 1.

[4] The initial Moravian settlement of the Wachovia Tract was begun in 1753 by a group of fifteen Single Brothers sent by Bishop August Spangenberg from Pennsylvania to North Carolina, arriving in their new land on 17 November 1753. Of the first settlers, four soon returned to Pennsylvania and other duties while eleven Single Brothers remained in the tract. They took up residence in a cabin that had been built on the land by a German named Hans Wagner, but who had not claimed the land and had moved to the Yadkin River. Around this small cabin they worked to establish Bethabara, the first Moravian town in Wachovia.

[5] Hermanus Loesch accompanied the first group of Single Brothers as a guide on their first trek from Pennsylvania to begin the occupation of the tract newly acquired by the Moravians. He had been intended to return immediately to Pennsylvania; however, his familiarity with the land and his skill as a forester made it necessary for him to remain in Wachovia with the other Single Brothers. Adelaide L. Fries (trans. and ed.), Records of the Moravians in North Carolina, Vol. 1 (Raleigh, NC: Edwards and Broughton Printing Co. for the North Carolina Historical Commission, 1922), 74.

[6] On 21 November 1753, the diary of the new Moravian settlement in Wachovia recorded, “Toward evening Br. Hermanus came back, having shot the first deer on our land. It was very welcome, for we had little food left, much work to do, and it is very hard to clear fields on a diet of corn only.” Ibid, 181.

[7] Ibid, 107.

[8] William Hinman, “Philip Christian Gottlieb Reuter First Surveyor of Wachovia” (M.A. thesis, Wake Forest University, 1985), 66–67, 96. Hinman refers to a July 1754 map showing a small portion of Bethabara as the earliest Moravian map from Wachovia. Regarding the Höger map discussed in the Moravian Records, Hinman dismisses it, saying, “finally the 1754 Höger map was rejected entirely due to the odd shape of the plots.” Hinman also questions the existence of a Höger map in Wachovia, saying, “if a copy was in fact retained in Wachovia, it cannot be located or identified in the MCA-SP at the present time [1985].” These comments reflect the general view of scholars of that period toward whether a Höger map of Wachovia existed.

[9] The use of the 1794 Boys’ School as a museum by the Wachovia Historical Society dated from 1896, the year following the formation of the society. The building had been vacant and the society used it to store their sizable collection, which was formed from an earlier collection begun in Salem by the Young Men’s Missionary Society, which existed from 1840 until 1894, and then from additional materials which were acquired by the Wachovia Historical Society after 1894. The first article in the society’s constitution was that, “The object of this Society shall be the collection, preservation and dissemination of everything relating the history, antiquities and literature of the Moravian Church in the South.” Bradford L. Rauschenberg, The Wachovia Historical Society 1895-1995, (Winston-Salem, NC: The Wachovia Historical Society, 1995), 8–51.

[10] After he chose the Moravian Tract in North Carolina in 1752 Bishop Spangenberg selected the name “Wachau” for it, after an ancestral estate of the Zinzendorf’s in Austria. This name immediately became Anglicized to “Wachovia” as seen on the Shot Deer map. This may have been done to make the name more accessible in English.

[11] Fries, 83, 330. The Irishman Sweeten and his family regretted having to move and asked the Brethren for compensation for the improvements he had made on the land. Although the Brethren felt they did not owe him anything, they paid him £15 because they “did not want him complaining about us.”

[12] Fries, 149.

[13] Ibid, 111. This diary entry for 19 October is an example of the detailed information recorded by the diarists of Wachovia through time, and the great value that level of detail can have for the researcher.

[14] The 1993 photograph of the map was taken when the map’s owner visited the Moravian Archives, Southern Province, in Winston-Salem. The archivists identified the map as an early representation of Wachovia but could not determine who had drawn it. The map’s owner gave permission for it to be photographed and, since the photographer was an Old Salem Museums & Gardens staff member, a print of the photograph was deposited with the Moravian Archives and another print was placed in Old Salem’s map files.

[15] Sarah Woodard David, personal communication with the author, June 2019.

[16] Construction of the town of Salem began in 1766 and in 1772 the congregation in Salem formally assumed the administration responsibilities previously held by Bethabara’s congregation.

[17] Fries, numerous entries.

[18] Hinman, 96. Hinman references this map as “n. d. (very early).” He states in his discussion of this map, “[not Reuter; has previously been suggested that possibly was drawn by a student, perhaps as a learning exercise?].”

[19] Appreciation for providing the digital color scan of the map is extended to Paul Peuker, Archivist at the Moravian Archives, Northern Province in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

[20] Fries, 111.

© 2019 Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts