Loudoun County, Virginia is located midway between Alexandria and the eastern edge of the Shenandoah Valley, two places where rich pottery traditions are well-documented. Hundreds of surviving pieces of pottery, historical records, and artifacts recovered through archaeological work clearly establish the potters, techniques, and trade of Alexandria and Shenandoah Valley pottery. A kiln site south of Leesburg discovered in 2004 offers a unique opportunity to consider the work of the forgotten potters of Loudoun County, and in particular, one family of potters whose tradition later reached as far as Missouri and Colorado.[1]

Sycolin Road Pottery

The Loudoun County kiln site was discovered in 2004 during the initial phase of a road-widening project and while it has not been fully excavated, it was surveyed by the Louis Berger Group, a cultural resource management contractor for the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT). Located along Sycolin Road, the site yielded remains of two kilns, waster piles, and an abundance of redware and stoneware sherds (Figure 1). Though some sherds had cobalt decoration and incised design that might be associated with a specific potter, none of the sherds revealed a maker’s mark, impressed or otherwise.[2]

Of known antique vessels, only one stoneware piece is marked as Loudoun pottery (Figure 2). The salt-glazed two-gallon jar, formerly in the private collection of John and Lil Palmer in Loudoun and now at MESDA as part of the William C. and Susan S. Mariner Collection, is impressed with the mark, “L. GARDNER / LOUN. VA.” (Figure 3). The jar’s cobalt decoration features two distinctive designs separated by rounded, eared handles. Both the circle and fern (Figure 4) and the swag and tassel (see Fig. 2) designs on this piece were popular motifs of the time, seen on Shenandoah and Alexandria works alike.

In the same private collection was another salt-glazed two-gallon stoneware jar (Figure 5), unmarked, that the collector believed was made in Loudoun and very likely by the same potter. John Palmer reported that for more than a hundred years, possibly since the 1840s, the jar had been owned by the Gover, Matthews, and Chamberlin families of Loudon, all of which were closely related with the Fairfax Quaker Meeting in Waterford (Figure 6).[3] This jar, also now at MESDA, suffered damage in the kiln but its hand-painted cobalt designs and retrieval history make it significant. A two-and-a-half story building with a single chimney appears on one side (Figure 7) and a profile of a bird decorates the other side (Figure 8). Incised double lines circle the jar, just above the lug handles that are more angular than those on the “L. GARDNER” jar (Fig. 2). According to MESDA’s chief curator Robert Leath, the structure on the front is “possibly a rendering of the Fairfax Quaker Meetinghouse in the town of Waterford in Loudoun” as it “bears a striking resemblance and layout to the gable end of the building, with a small shed-roofed structure and a fireplace located on the side.”[4]

Ceramics expert Robert Hunter, a consultant to Louis Berger who had examined wasters and smaller sherds, attributed the house jar (Fig. 5) to the Sycolin Road kiln and dated the kiln to 1820 to 1840. Other surviving pieces from the Sycolin site likely exist and have either been attributed to another pottery or not attributed at all, which is not surprising since so little information had been collected on Loudoun’s potters.[5]

Gardner-Duncan Family in Loudoun

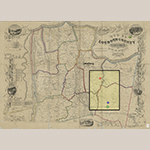

The names and relationships of all Loudoun potters are not all known and yet compelling connections spanning four generations have been established for those associated with the Sycolin kiln. Members of the Gardner and Duncan pottery families lived and worked in Loudoun and in northeastern Missouri from the late eighteenth century to late nineteenth century (Figure 9).[6]

The Gardner-marked jar (Fig. 2) can be attributed to Charles Lewis Gardner (ca.1778–1850) who was known by his middle name. Though records with his name appear with varying versions and spellings, Lewis Gardner is the only “L. Gardner” found consistently among Loudoun’s early nineteenth-century records and the 1810 census places Lewis in the Waterford area in northern Loudoun with his young family.[7]

In 1800, Lewis Gardner married Nancy Duncan (ca.1778–1820), whose family had established an earthenware manufactory in Loudoun. Nancy’s father Charles Duncan (ca. 1747–1807), originally from Westmoreland County, Virginia, operated a pottery in eastern Loudoun where he purchased 226 acres along Broad Run in 1777.[8]

An entry in merchant Israel Janney’s ledger shows that in 1785 Charles Duncan supplied his store, approximately 15 miles northwest of the Duncan property, with “Earthen Ware” and “1/2 Doz Pichers.” Credited with £6. 6s. 9d. for the earthenware order and 3s. 4d. for the pitchers, Charles purchased a book, pewter plates, linen, red flannel, needles, shirt buttons, and other materials from Janney.[9]

Later records indicate that Charles used some of his pottery production as payment on outstanding debts. Following Charles’s death in 1807, a Stephen Beard submitted documentation to the estate stating that Charles had paid him “Seven pounds Eleven Shillings & three pence” in “Earthen ware” and “twenty two dollars & one cent” in “Crockery ware.”[10]

Charles’s probate inventory listed a “Set Clay Mill Iron” valued at $2 and “Beaufat & Crockery Ware” valued at $7. Earthenware was often recorded in estate appraisals and perhaps was paired with the “beaufat,” or buffet, because it had been displayed or stored in such a furniture form. The clay mill irons in the inventory are truly significant, confirming a link to pottery manufacturing, as such tools were used to prepare clay for ceramics production and brick making.[11]

In addition to their daughter Nancy, Charles and his wife Susanna Mason (ca.1755–1827) had nine other children, including several sons who worked in the family pottery business. An 1826 deposition of Jeremiah Bronaugh Jr., in a chancery suit brought by Jonathan Reid against the Duncan family, confirms the involvement of two Duncan sons, Henry (ca.1789–ca.1875) and Mason (ca.1795–1833), in the family’s “potter’s ware manufactory.” Bronaugh recalled seeing Henry and Mason “frequently delivering potters ware to different stores” in the county. Further, Duncan sons George (ca.1788–1855) and Benjamin (ca.1798–1857) are both documented as potters, with George working in Loudoun County and Benjamin in northeastern Missouri.[12]

Duncan daughter Nancy and her husband Lewis Gardner had at least five children, three of whom were potters. William H. (ca.1815–1892) remained in Loudoun, while James B. (ca.1809–1868) and George Mason (1816–1902) moved to Marion County, Missouri, where both worked as potters. The family trade continued for several decades and to a fourth generation through the sons of James and George Gardner.

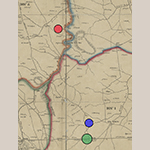

As for the Sycolin pottery, it is highly likely that Lewis Gardner, and perhaps his brother-in-law George Duncan, worked there, probably after 1817 when the Duncans sold off a large part of their land. Property records from the time document the Sycolin parcel’s owners and Lewis Gardner is not among them. In fact, he did not purchase land until 1839 and that property was along Broad Run, about five miles south of the Sycolin kiln and closer to the tract once owned by the Duncans (Figures 10 and 11).[13] However court records support the argument that in the 1820s Lewis Gardner operated the Sycolin kiln.

The Sycolin kiln site is located on a parcel then known as Egypt Farm, and from 1819 to 1826 its owner Thomas R. Mott leased it out. It was just after Mott’s death in 1826 that the strongest connections between Lewis Gardner and Egypt Farm can be established. In an inventory, the executor recorded debts owed to Mott’s estate and included a judgment against “L. Garner [sic] for rent.” Though the citation does not specify that the rent is for property at Egypt and an earlier court order simply lists the parties and not the details of the suit, it is likely that the rent Lewis Gardner owed was for the kiln site property.[14]

This is supported by an 1827 agreement that Lewis and Matthew Orrison, who had married Lewis’s daughter Elizabeth three years earlier, signed in order to secure a third party’s payment to Mott’s administrator on their behalf. Lewis and his son-in-law agreed to put up their own personal property as security, including “$250 worth of potters wares,” “2 glazing stands,” and “3 turning lays” that Lewis owned.[15]

By the time of the 1840 census, Lewis was living on the Broad Run property, closer to the town Arcola than to Leesburg. That census recorded three members of his household as working in manufacturing. All three were adult males and, based on the age ranges, two of them would be the now-widowed Lewis and his son William. The third could well have been his brother-in-law George Duncan, for George’s name was not listed elsewhere in the Loudoun census records that year and his age fell within the recorded range of fifty to sixty years old.[16]

Like William Gardner, George Duncan’s work as a potter is established through documents. George was listed in the 1850 census as a sixty-two-year-old potter residing near present-day Arcola. Living very near the unmarried George were other Gardner family members and a woman named Frances Harding and her young son, Henry. William Gardner was named in the 1860 population census as a potter, about forty-three years old, and like his uncle ten years earlier, living in eastern Loudoun. He made his home with Frances Harding and her two boys, including sixteen-year-old Henry who was identified in that census an “Apprentice potter.”[17]

While the 1820 manufacturing census revealed extensive details about the pottery operations in Alexandria and Richmond, there was no mention of such a manufactory in Loudoun, perhaps because that census only captured businesses producing wares worth $500 or more annually. Forty years later, the 1860 industrial census valued William Gardner’s annual production of pottery at $1,000 (Figure 12). The operation consumed sixty tons of clay and a thousand pounds of lead, indicating his wares were indeed glazed. Three men supplied labor at a monthly cost of $30. No vessels or sherds bearing William’s mark have been documented and it is only this limited information that sheds light on his pottery production. William H. Gardner died in 1892 and left no will, property, or descendants.[18]

Gardner-Duncan Family in Missouri, Colorado, and Illinois

The Gardners and Duncans who made their way west continued the family trade and like their Virginia kin, their work as potters is mostly known through documents rather than through vessels, maker’s marks, or shared decorative motifs.

Several of Charles and Susanna Duncan’s children settled in Missouri. Daughters Catharine (ca.1784–1867) and Susanna (ca.1791–1844) and son Henry left Loudoun not long after their mother’s death in 1827 and later made their home in St. Louis. In 1829, sons Benjamin and Mason moved to Marion County, which borders the Mississippi River in northeast Missouri. With clay an abundant natural resource in Marion County, Benjamin and Mason established a pottery in the town of Palmyra soon after their arrival.[19]

In 1832, Benjamin Duncan entered into a business agreement with Charles H. Allen, an attorney who would provide materials to Benjamin’s kiln. Allen agreed to supply wood, clay and salt, and Benjamin agreed to hire another person, presumably his brother Mason, who “understands the business of making eathen [sic] and Stone ware.” They would attend to the operation “according to their skill and Judgement as potters in the pottering business,” and Allen would pay Benjamin what he would “reasonably deserve.”[20]

This arrangement appears to have been made to fund the Duncan pottery after a civil suit judgment against Benjamin created financial strain on his business. The contract does not detail the nature of the dispute with a third party but does describe the Duncan kiln output as “Potters ware consisting of crocker bowles, Jugs & Pitchers.” What came of this partnership is unclear as a devastating cholera epidemic struck Palmyra within the year, killing Mason Duncan in 1833.[21]

Benjamin, his wife and two children survived the epidemic, including his son John Coleman Duncan (1829–1900) who also would follow in the family trade, at least for a time. The 1850 industrial census noted the Duncan “stoneware manufactory” yearly production as five thousand gallons of ware worth $500. Shortly after that census was taken, John left the family business and moved to California as many did following the discovery of gold. He later returned to Palmyra, but not to potting. When his father died in December 1857, John was appointed administrator of Benjamin’s estate.[22]

An estate appraisal includes assets of a “Potters wheel Spindle & head” valued at $5 and a lot of “Stone Ware supposed to be 5000 gallons at 8 cts a gallon” valued at $400. However, it is debts owed to the estate that provide the best picture of Benjamin Duncan’s pottery production. Silas Terry submitted two bills, one prior to Benjamin’s death and one after, for “Turning ware” and “Setting & Burning Kiln.” Whether Terry was a regular worker at the Duncan pottery or one who assisted in the final months of Benjamin’s life is not known, but he did turn out more than 4,000 pieces between November 1857 and February 1858.[23]

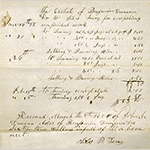

Terry’s invoices totaling $115.22 reveal his cost per piece generally ranged from one to two cents a gallon (Figure 13). For example, he charged one cent for turning each half-gallon jug and two cents for turning each one-gallon jug. Charges for larger pieces were priced by the gallon, but with consideration for the job, with a lower rate for pots that did not require the complex handles and necks that jugs did. For turning twenty-five six-gallon pots during the week of 19 December 1857, Terry charged a total of $2.25 or a cent-and-a-half per gallon. The same rate of one-and-a-half cents applied to fifty-nine four-gallon pots Terry turned that same week. These invoices reveal not just the labor rate, but the variety of wares with pans, jars, pots, jugs, and churns all turned and fired at the Duncan pottery following Benjamin’s death.[24]

The production may well have been rather sizable, because in December 1858 administrator John C. Duncan submitted a note to the estate for $25 for additional labor expenses. The money was owed to another man for the hire of a “Negro boy…to assist in completing two unfinished kilns of ware begun by my father.” But after 1858, there is no evidence of further operation of Duncan’s pottery. Despite the fact that son John bought his father’s potter’s wheel for $1.50 at the estate sale, he never engaged in pottery again and it would be up to his Gardner cousins to continue the family tradition.[25]

Benjamin Duncan’s nephews, James B. and George Mason Gardner, the sons of Lewis Gardner, both moved from Loudoun County to Missouri. James arrived around 1828, just before Benjamin and Mason Duncan. James, and then George, settled in Marion County where both would pursue pottery for the next thirty years or so.[26]

According to 1850 census records, James and George were both living with their own families in Fabius Township, just north of Palmyra, and working together at their own pottery where four workers produced $1,000 worth of stoneware a year (Figure 14). In 1857 James sold a large tract of land to George, probably his part of the land where the pottery operation was based. James moved to Warren Township and though identified in the 1860 population census as a farmer, he was still heavily involved in pottery. The industrial census valued his annual production of stoneware at $1,900 (Figure 15), and a German immigrant potter was among the Gardner household members that year.[27]

Twin stoneware pitchers with the year “1867” in cobalt that are currently in a private collection can be attributed to James. One is inscribed with his name “J.B. Gardner” (Figures 16 and 17) and the other with his wife’s name, “Martha Gardner” (Figure 18). Both have bulbous bodies and flared collars and feature incised and cobalt decoration, with brushed cobalt ferns, incised and cobalt flowering plants, cobalt at the terminals of the handles, and double incised lines circling the neck just below the spout.

James B. Gardner died in 1868 and his estate appraisal hints at the likelihood that he not only produced traditional pottery wares, but also bricks. Two potter’s wheels were valued at $10 each, a clay picker at $6, and four “Brick Moulds” at 25 cents apiece. Though his youngest son, Joseph T., remained committed to the farm and its fruit orchard, the two oldest pursued the family business, but in Colorado.[28]

James Albert Gardner (1848–1879) moved to Denver, Colorado, probably around 1871, and reportedly established one of the first potteries there. Albert also served as a firefighter with the Hook and Ladder No. 2 company and his business partner, Scott Arbuckle, was a member of the same firehouse. The business, known as “Gardner & Arbuckle,” operated at the corner of Arapahoe and 22nd streets.[29]

A few years later, Albert’s brother, Charles L. Gardner (1846–ca.1901), moved to Denver and joined the brick making and pottery manufactory. Charles became a partner in 1878 and the business, known simply as “Gardner Brothers,” remained at the same location. According to an 1879 advertisement, they produced “Flower-pots, Drain-tile, Fire-Brick and Stove Lining” (Figure 19). When Albert died the following year, Charles took over all aspects of the operation and what became of the Denver pottery is uncertain, as the “Gardner Brothers” disappear from the local business directories after 1880.[30]

Back in Missouri, their uncle, George Mason Gardner, operated his pottery near the South Fabius River into the 1870s and likely several years later. The 1860 industrial census documented his annual output of wares as 14,000 gallons and 4,000 half-gallons worth nearly $1,300 (Figure 20), but by 1870 production was down. Market competition in Marion County had become tight with at least eight potteries producing wares in 1870 and with half of those operating year-round. The other four, George Gardner’s among them, only ran about three months each year and produced about one quarter what the larger potteries in Palmyra turned out. Still, George’s pottery was clearly marked on an 1875 county map (Figure 21) and in 1880, the Palmyra Spectator noted that he was “largely engaged in the manufacture of earthen ware.”[31]

Of all George Gardner’s children, only son Corbin (ca.1855–ca.1912) is positively identified as a potter. In 1880 Corbin was living in Hannibal, the largest city in Marion County, and working there as a potter. In the 1890s George Gardner sold his 160 acres in Fabius for more than $10,000 and moved across the Mississippi River to Quincy, Illinois. He lived there with son Corbin who by then had left the pottery industry and begun working for the railroad. In Quincy, George used his knowledge and experience with clay to develop hollow fence posts made of “terra cotta vitrified.” He partnered with Sanford C. Pitney and together they obtained two patents for baked clay posts for wire fencing (Figures 22 and 23). George Gardner died in 1902, and after four generations and more than a hundred years, the Gardner-Duncan pottery line came to an apparent end. George was buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery, a short distance from his old land and pottery.[32]

In 2006, the owner of the former Gardner property reported that the land had been in his family since the mid-1950s. Until about 1985, family members would regularly find sherds of grey and “clay colored” pottery on the northeast corner of their land. They found both curved and flat sherds, some glazed on one side. Sherds are no longer visible at the surface because the land is used for cattle farming and remaining sherds would be covered by soil and manure.[33]

New Opportunities

A couple years after the discovery of the Sycolin kiln, a second jar marked as Loudoun was located in a local private collection. The glazed redware piece is mended and bears no distinctive decoration, yet the inscription on the base is significant. Within a triangle cursive lettering reads, “Lees / burg / Louden / County Va / 1843” and outside the triangle to the right the same lettering reads, “Gum Spring” (Figure 24). The glaze, probably manganese, is identical to that found on some of the sherds at the Sycolin kiln site, but the community of Gum Spring, now called Arcola, is several miles south of the Sycolin site. Based on the date and location alone, it seems the jar was made by George Duncan or Lewis or William Gardner at another kiln. The land the Gardners owned in the 1840s was part of the Arcola community and quite close to the land Lewis Gardner’s in-laws owned along Broad Run when they operated their pottery at the turn of the century.[34]

The discovery of this jar and the archaeological excavations at the Sycolin kiln site would be enough to consider that Loudoun pottery was much more than an experiment in the early 1800s. When the lives of the Gardner and Duncan families are examined, it becomes clear that their pottery work was successful and yet their wares have not been identified.

Full excavation of the Sycolin kiln presents the best opportunity to learn more about Loudoun pottery and this family’s work, and careful examination of unattributed and even previously attributed pieces may offer another dimension. On the farms of northeast Missouri and beneath development’s bulldozers in northern Virginia, the lost potters of Loudoun County await rediscovery, finally receiving proper recognition. That the Loudoun jars John and Lil Palmer discovered and added to their significant and extensive collection are now exhibited at MESDA reflects a growing awareness and appreciation of the rarity and cultural value of work produced by the Gardner-Duncan family of potters.

Amy Bertsch is a historian and an adjunct instructor in the Public History and Historic Preservation certificate program at Northern Virginia Community College. She has a master’s degree in history from Sam Houston State University and previously worked for the Office of Historic Alexandria in Alexandria, Virginia. She can be contacted at [email protected].

[1] This article grew out of a semester project for a historical archaeology course at Northern Virginia Community College. After the course ended, my research continued and led to the links in Missouri and beyond. I’m extremely grateful to Dr. David T. Clark and the late Catherine Peck for their encouragement, to the late Mary Ann Dobson, to Barbara Magid, Gary L. Maize, the Zipp family, and the late Thomas Hyland for their assistance and insights, and most of all, to the late John and Lil Palmer for sharing their pottery collection, knowledge, and kindness.

[2] John J. Mullin, Megan Rupnik, and Robert Hunter, Archaeological Survey of Route 643 (Sycolin Road) and Archaeological Evaluation of Site 44LD1195, prepared for the Virginia Department of Transportation (Richmond, VA: The Louis Berger Group, Inc., September 2006).

[3] John C. Palmer, interview with the author, October 2005; see also online catalog record for MESDA, The William C. and Susan S. Mariner Collection, Acc. 5813.30: https://mesda.org/item/collections/jar/21223/ (accessed 13 July 2019).

[4] MESDA, The William C. and Susan S. Mariner Collection, Acc. 5813.30: https://mesda.org/item/collections/jar/21223/ (accessed 13 July 2019).

[5] Mullin, et al., Archaeological Survey of Route 643 (Sycolin Road) and Archaeological Evaluation of Site 44LD1195, 55.

[6] Records show varying spellings for both Duncan and Gardner, with Dunkin and Garner as the most common variations. For clarity, this article will use Duncan and Gardner unless quoting a specific reference.

[7] Loudoun County, VA, Personal Property Tax Records, 1800–1853 (Microfilm collection of Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA), and Will and Deed Books, 1800–1853 (Clerk of Circuit Court, Leesburg, VA).

[8] Loudoun County Marriage Record, 1793-1850 (Clerk of Circuit Court, Leesburg, VA), 12; Loudoun County Deed Book L (Clerk of Circuit Court, Leesburg, VA), 341–343. Note: Duncan family history holds that as a young man, Charles Duncan had lived for a time in Massachusetts and learned the craft of pottery there after traveling north with his brother-in-law, the captain of a merchant ship. Family histories recall that Charles traveled to Massachusetts, probably between 1760 and 1770. Certainly there was ample opportunity to learn the trade in colonial Massachusetts with dozens of redware potters well established in Charlestown, Danvers, Gloucester, and other towns, but a review of records has failed to confirm this family history. For more on Duncan family history and early Massachusetts potters, see Lillian Parrish Overstreet, Kentuckians of Yore and Kinsmen Galore (Utica, KY: McDowell Publications, 1986), 103–104; Nancy Reba Roy, The Henry-Coleman Duncan Family, Descendants of Peter Duncan of Westmoreland County, Virginia (La Mesa, CA: Nancy R. Roy, 1964); and Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1950).

[9] Israel Janney, Israel Janney’s “Ledger B,” 1784–1793, edited by Werner and Asa Janney (Lincoln, VA: Sign of the Pied Typer, 1989), 98.

[10] Loudoun County Partially Proven Wills and Deeds, Charles Duncan estate documents, Book 1 (Clerk of Circuit Court, Leesburg, VA), 100131.

[11] Loudoun County Will Book H (Clerk of Circuit Court, Leesburg, VA), 172.

[12] Chancery Suit M2015, Reed v. Dunkin, et al. (Clerk of Circuit Court, Leesburg, VA).

[13] Chancery Suit M6732, Dunkin v. Reid (Clerk of Circuit Court, Leesburg, VA), Loudoun County Deed Book 4O (Clerk of Circuit Court, Leesburg, VA), 113–114.

[14] Loudoun County Will Book Q (Clerk of Circuit Court, Leesburg, VA), 150-152; Loudoun County Will Book Q (Clerk of Circuit Court, Leesburg, VA), 243–245.

[15] Northern Virginia Genealogy, Marriage and Death Notices from the Genius of Liberty (Bluemont, VA: Northern Virginia Genealogy, 2005), 34; Loudoun County Deed Book 3-O (Clerk of Circuit Court, Leesburg, VA), 346–349.

[16] Bureau of the Census, Sixth Census of the United States 1840: Population Schedule, Eastern District, Loudoun Co., VA.

[17] Bureau of the Census, Seventh Census of the United States 1850: Population Schedule, Loudoun Co., VA; Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census of the United States 1860: Population Schedule, Arcola, Loudoun Co., VA.

[18] Bureau of the Census, Fourth Census of the United States 1820: Census of Manufactures, Washington, D.C., and Virginia; Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census of the United States 1860: Products of Industry, Loudoun Co., VA; Loudoun County Register of Deaths, 1892 (Clerk of Circuit Court, Leesburg, VA).

[19] Bureau of the Census, Fifth Census of the United States 1830: Population Schedule, St. Louis, MO; Will of Catharine Duncan, Probate Record #8218, St. Louis County Clerk of Court; Will of Susanna Duncan, Probate Record #1982, St. Louis County Clerk of Court; E.F. Perkins, History of Marion County, Missouri (St. Louis: E.F. Perkins, 1884), 673 and 759; G.C. Swallow, First and Second Annual Reports of the Geological Survey of Missouri (Jefferson City, MO: James Lusk, 1855), 171–173.

[20] Marion County Deed Book B (Clerk of Court, Palmyra, MO), 128.

[21] Marion County Deed Book B (Clerk of Court, Palmyra, MO), 128; Perkins, History of Marion County, Missouri, 194.

[22] Perkins, History of Marion County, Missouri, 759; Bureau of the Census, Seventh Census of the United States 1850: Products of Industry, Warren, Marion and Round Grove Townships, Marion Co., MO (Collection of the State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia, MO); Probate Record of Benjamin Duncan Estate (Clerk of Court, Palmyra, MO), settled 1867.

[23] Probate Record of James B. Gardner Estate (Clerk of Court, Palmyra, MO), settled 1881.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Marion County Deed Book B (Clerk of Court, Palmyra, MO), p. 122–123.

[27] James B. Gardner to George M. Gardner, Deed #12667 (Clerk of Court, Palmyra, MO); Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census of the United States 1860: Population Schedule, Warren Township, Marion Co. MO; Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census of the United States 1860: Products of Industry, Warren, Miller and South River Townships, Marion Co., MO (Collection of the State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia, MO).

[28] Probate Record of James B. Gardner Estate (Clerk of Court, Palmyra, MO), settled 1881; Perkins, History of Marion County, Missouri, 696.

[29] Denver Daily Tribune, 6 July 1878; Denver Daily Tribune, 18 March 1879; T.B. Corbett, W.C. Hoye, and J.H. Ballenger, Corbett, Hoye & Co.’s Sixth Annual City Directory (Denver, CO: Corbett, Hoye & Co., 1878), 125.

[30] O.L. Baskin & Co., History of the City of Denver, Arapahoe County and Colorado (Chicago: Baskin & Co., 1880), 453; J.A. Blake, Colorado State Business Directory (Denver: J.A. Blake, 1879), 111.

[31] Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census of the United States 1860: Products of Industry, Palmyra, Marion Co., MO (Collection of the State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia, MO); Bureau of the Census, Ninth Census of the United States 1870: Products of Industry, Fabius Township, Marion Co., MO (Collection of the State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia, MO); Thaddeus M. Rogers, Atlas of Marion County, Missouri (Quincy, IL: T.M. Rogers, 1875), 53; “Hannibal Budget,” Palmyra Spectator, Palmyra, Missouri, 9 April 1880.

[32] Bureau of the Census, Tenth Census of the United States 1880: Population Schedule, Hannibal, Marion Co., MO; George M. Gardner to Albert G. Smith, Deed dated 20 January 1899 (Clerk of Court, Palmyra, MO); Bureau of the Census, Twelfth Census of the United States 1900: Population Schedule, Quincy Township, Adams Co., IL; Sanford C. Pitney and George M. Gardner, Fence Post, U.S. Patent 532,246, filed 27 June1894 and issued 8 January 1895 United States Patent and Trademark Office, Alexandria, VA; Sanford C. Pitney and George M. Gardner, Clay Post, U.S. Patent 558,418, filed 14 October 1895 and issued 14 April 1896 United States Patent and Trademark Office, Alexandria, VA; G. M. Gardner tombstone, Mount Olivet Cemetery, Taylor, MO.

[33] Morris Gottman, correspondence with the author, February 2006.

[34] Eugene M. Scheel, Goin’ Down the Country (Westminster, MD: Willow Bend Books, Inc., 2002), 93-95 and 151-152.

© 2019 Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts