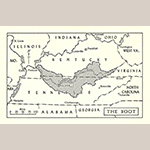

The Cumberland is not just the famous river that shares its name. The region is neither Tennessee nor Kentucky and both make up this unique place (Figure 1). Kentucky-born novelist and social historian Harriette Simpson Arnow discussed the region in Seedtime on the Cumberland. She best characterized the Cumberland in her book’s first chapter, aptly titled “The Old Boot”:

The drainage basin [of the Cumberland River] forms a curious, shoe-like shape, something like an old-time buskin, badly worn and wrinkled, with a gob of mud caught in the instep, blurring the heel, yet with all the parts of a foot covering. The long and narrow toe, lifted as if for kicking, touches the Ohio, the wrinkled heel goes southward onto the high tableland of the Cumberland Plateau and is shaped by the Caney Fork river and its tributaries. The top of the shoe is formed by the Rockcastle and its many crooked creeks, a rough country the old ones found as they went through it on their way to the Kentucky Bluegrass.[1]

Arnow and historians before her recognized that the Cumberland had lost its identity by the time the states of Kentucky and Tennessee were formed and saw importance in distinguishing the region and pointing out its historical significance.

A fortuitous encounter—now over thirty years ago—with an impressive rifle made by Jacob Young for William Waid Woodfork began my own lifelong quest to preserve the Cumberland’s distinct identity. That rifle inspired my continuing passion to study the artisans who lived and worked in this enigmatic region of early America and to foster greater admiration for the remarkable objects they produced.

The individuals discussed in this article all lived in the Cumberland. The rifles and powder horns they made or owned speak directly to their pioneer lives on the southern frontier. The artistry found in these objects may be unexpected but reflect the rich resources and abundance of talent found along the Cumberland’s rivers and thoroughfares.

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

Elegant in its simplicity, the long graceful firearm made by Jacob Young for William Waid Woodfork was built around an exquisite handmade flintlock stamped by the gunsmith (Figures 2 and 3). The flintlock—the heart of every rifle—was painstakingly wrought at a time when high-quality English locks were readily available to nearly every American gunsmith. Producing the lock alone surely took more time and effort than making all the other components of the rifle combined. The fact that Young handcrafted this lock reflects his skill as a gunsmith as well as the pride he took in his skills.

Both the priming pan and the enclosure of the frizzen are lined with pure gold; a gold flash guard, dovetailed into the iron of the barrel, surrounds a gold touchhole liner. The bolts holding the lock are overlaid with silver and rest upon a silver sideplate designed with a candle-flame-shaped finial (Figure 4). Upon this sideplate, prominently engraved in beautiful script, is the owner’s name: “Wm. Waid Woodfork.” The patchbox was fashioned from a single piece of cast brass and expertly fitted with a captured lid—one that did not extend to the buttplate—encircled by a delicately engraved surround (Figure 5).

The trigger guard is also unique, constructed with a reverse curve at the termination of the grip rail kissing the rear support of the guard. The cheekpiece holds the largest of a dozen silver inlays: a large elongated diamond decorated with a skillfully engraved Federal eagle (Figure 6). No screws or pins visibly attach this inlay, and further investigation found it is held in place by a pin inserted from under the cheekpiece. To affix the inlay in this manner was an arduous task, but one obviously important to Young so that nothing distracted from or would dislodge his decoration. Such durability was essential in a longrifle as it was the most important tool of the day.

Men lived with their rifles in their hands, ready to ride to the aid of a distant station or to pursue a war party making off with prisoners and/or stolen horses. A man often stood guard with a rifle while others milked the cows or plowed the fields. It was unusual to see a man without a rifle and it was always loaded and primed. Someone caught with an empty rifle might easily pay for his negligence with his life. As an indispensable companion, a good rifle was respected and carried with great pride. The quality, beauty, or artistic merit of one’s rifle was a mark of status.

Jacob Young was a second-generation gunsmith, born 8 May 1774 on the southwest frontier of Virginia. The child of William Young and Elizabeth Huff, by the time Jacob was three years old his family had relocated to Rowan County, North Carolina. William Young was an armorer under the command of General Griffith Rutherford during the Cherokee campaigns. In 1779 he moved his family again, from Rowan County to the Cumberland, settling on Indian Creek near modern-day Boma, Tennessee, located in what was then Sumner County, North Carolina.

William Waid Woodfork was an early pioneer in Jackson County, Tennessee, owner of a large plantation, and an influential man. Woodfork was a surveyor and in 1806 was paid by the state of Tennessee to separate White County out of Jackson County. William H. Speer, in Sketches of Prominent Tennesseans, writes that Woodfork “was a man of fine ability and large fortune, being one of the richest men in Tennessee… .”[2] He was also a noted horseman:

Tennessee was far in advance of Kentucky prior to the war [1812] in thoroughbred horses, the development of this animal dating back to 1808 in the vicinity of Nashville and the breed improved by the judicious expenditures of money by such men as the immortal Andrew Jackson… and William Waid Woolfolk, of Davidson county.[3]

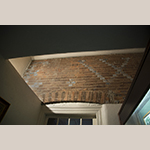

Jacob Young also made a fine rifle for early Kentucky frontiersman William Whitley, who was born in Virginia in 1749 and moved to Kentucky in 1775 (Figures 7 and 8). Whitley served under George Rogers Clark during the Revolutionary War, was a state legislator, and fought multiple campaigns against several American Indian tribes. He called his Cumberland home Sportsman’s Hill (Figure 9), which is noteworthy as one of the first brick houses built west of the Allegheny Mountains but is even more significant as the site of one of America’s first circular racetrack for horses. In defiance of British norm, Whitley arrogantly raced horses on his track counter-clockwise, which American horse races still run today. The estate also earned another moniker, “Guardian of Wilderness Road,” as the gathering place for numerous early frontiersmen including Isaac Shelby, John Sevier, James Hankla, George Rogers Clark, and Daniel Boone.

Built between 1787 and 1794, Sportsman’s Hill is an architectural masterpiece of the early Kentucky frontier. Prominently placed above the front entrance, Whitley’s initials “W W” formed with glazed headers set the ambiance of the brick fortress (Figure 10). Circling the house, bricks laid in Flemish bond make a diamond pattern decorating each gable end (Figure 11). Equally as bold as Williams’s initials on the front of the house, the initials “E * W” for his wife Ester Whitley are found on the rear façade (Figure 12). What was a rear exterior wall of the house is now enclosed within a modern structure. The main part of the first floor interior contains three rooms that feature exceptional architectural woodwork completed by a very talented but unknown craftsman. To the left of the front door is a high-ceilinged drawing room with thirteen S-shaped woodcarvings adorning the walnut block paneling of the fireplace (Figures 13 and 14). The main stairway, connecting the lower and upper halls, is also exceptionally crafted, decorated on the end of each step with an eagle holding an olive branch (Figures 15 and 16).

Stylistically, the rifle that Jacob Young crafted for William Whitley appears to have been made several years earlier than the one Young made for Woodfork (Fig. 2), probably around 1800. The butt is considerably wider (1-3/4 inches) and is designed with a stepped wrist (Figures 17 and 18). The butt has been broken through the wrist and carries a tidy brass repair. Stamped “H. Deringer-Philad,” the flintlock is a period replacement (Figure 19). Although not as elegant as Woodfork’s rifle, it is decorated with bold relief rococo carving, exhibiting another facet of Jacob Young’s talent and artistry.

The script engraved on Whitley’s rifle (Figure 20) mirrors the large, gracefully curved powder horn that Young made to accompany it (Figures 21 and 22). The horn is inscribed:

Wm. Whitley I am your horn

The truth I love , A lie I scorn

Fill me with the best of powder

Ile make your rifle crack the louder

See how the dread terrifick ball

Make Indians bleed and Tories fall

You with powder Ile supply

For to defend your Liberty

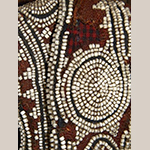

Passed down with Whitley’s rifle and the powder horn is an extremely rare elaborately beaded strap (Figure 23). Finger woven from spun wool, it was originally longer and appears to have been cut down in length specifically to carry the rather enormous powder horn. Research suggests that it is probably a “bandolier sash” and the spiraling beaded designs are Chickasaw in origin (Figures 24, 25, and 26). This would make sense as Whitley was one of the commanding officers in the 1794 Nickajack Expedition against the Chickamauga, serving alongside Chickasaw Chief Piomingo, an early American Indian diplomat honored by George Washington for his unyielding peace initiatives.

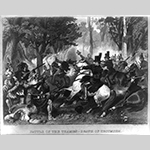

According to tradition, William Whitley carried this rifle and powder horn to the Battle of the Thames, in Ontario, Canada. He was killed there on 5 October 1813. He was sixty-four years old at the time, yet enlisted as a private in John Davidson’s company that formed a part of Richard Mentor Johnson’s Kentucky Mounted Infantry. In all of Whitley’s campaigns he had been wounded only once, but the night before the Battle of the Thames, Whitley is said to have expressed the belief to his friend, John Preston, that he would die on the following day. At the onset of the battle, to avoid sending the entire regiment into an ambush, Commander Johnson called for twenty volunteers to draw fire from Tecumseh and his warriors. While Johnson rode beside the little band, at its head rode William Whitley. During the first volley of the engagement, nineteen of the group were unhorsed and fifteen were mortally wounded. When the skirmish ended, both Tecumseh and William Whitley were dead.

Richard Spurr, a private in Samuel Comb’s company and one of those volunteers who rode with Johnson, stated later in life that he had seen Whitley and an Indian, whom he recognized as the the Shawnee leader Tecumseh, fire at one another and that each was killed (Figure 27). Spurr carried the bodies of both Whitley and Tecumseh into camp with General Harrison. John Preston, who survived the battle, returned Whitley’s horse, rifle, and powder horn to Ester Whitley.

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

As previously mentioned, in 1776 the gunsmith Jacob Young’s father, William Young, was in the Watauga region of what is now East Tennessee as an armorer under General Griffith Rutherford. Also in the Watauga that same year was Thomas Simpson. The pension application for Joseph Luske reveals that both he and Simpson were in Captain John Sevier’s company on William Christian’s campaign against the Cherokee. Luske declared that his messmates were, “Thomas Simpson — armorer, Felix Walker, Julius Robinson and William Dodd.” All of these men were signers of the 5 July 1776 “Watauga Petition” for annexation of the region into North Carolina.[4] In May 1772, for the mutual protection of the settlements along the Watauga, Holston, and Nolichucky rivers, the frontier settlers had created a semi-autonomous government called the Watauga Association. President Theodore Roosevelt later wrote: “the Watauga settlers were the first men of American birth to establish a free and independent community on the continent.”[5] Although only lasting a few years, the Watauga Association provided a firm foundation for what later developed into the state of Tennessee.

The shared regional origin of Jacob Young and Thomas Simpson could explain stylistic similarities that exist in their work, although their age difference must be kept in mind. Jacob would have only been two years old when his father served alongside Thomas Simpson in 1776 and thirteen years old in 1787 when his father and Thomas Simpson were first recorded on tax rolls in the Cumberland. Some scholars of the American longrifle feel that perhaps Jacob Young apprenticed to Simpson; however, no documentation has been found to support this theory, but they did live in close proximity and have early roots in the Watauga.

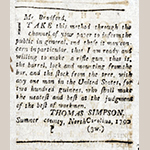

The 26 July 1790 issue of the Kentucky Gazette (Fayette County) published a notice from Thomas Simpson: “I am ready and willing to make a rifle gun, that is, the barrel, lock and mounting from the bar, and the stock from the tree, with any one man in the United States…” (Figure 28). His address was listed as Sumner County, North Carolina. Formed in 1786, Sumner County encompassed what is today is eastern Davidson and most all of Robertson, Wilson, Macon, Smith, and Trousdale counties of Tennessee.

A year later, in 1791, Simpson made a masterpiece rifle for Colonel Gasper Mansker (Figures 29, 30, 31, and 32). The rifle is elaborate and probably took months to build, making it most likely the first rifle Simpson produced after his newspaper notice. The style and lines of this rifle are sleek and graceful, shaped around a hand forged .50 caliber barrel just shy of four feet in length. The stock is fashioned from exceptional maple wood with brilliant curly grain, and bold relief carving flows from butt to muzzle (Figure 33). Sand-cast brass mountings are artistically sculpted and expertly engraved (Figures 34, 35, and 36). Silver accents adorn the wrist, toe, cheek, and heel (Figure 37).

Mansker was acquainted with Simpson before he commissioned the rifle as the two men carried chain on a 640-acre survey on Maddison’s Creek in February 1789. Two years later, in April 1792, the Commissioners of North Carolina deeded this tract to Thomas Simpson for £100. The property was within a mile of Mansker’s station.

Thomas Simpson wanted there to be no doubt that he crafted this exceptional rifle and made sure to engrave the Latin term fecit (meaning, “he did it”) adjacent to his signature on the silver plate affixed to the top flat of the barrel (Fig. 31). “G. Mansker” is inscribed on the patchbox door’s silver overlay (Fig. 30). Mansker’s ownership is further documented by a rare document, a 17 June 1793 letter from Chickasaw Chief Piomingo to Indian Agent General James Robertson stating, “I want you to get Simson [sic] to make me a gun like Col. Mansker’s.”[6]

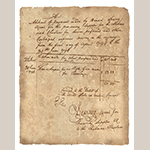

The rifle for Piomingo was completed by 30 June 1794 when Bennet Searcy, agent for procuring supplies, recorded payment to Thomas Simpson. The receipt states: “Thomas Simpson for one Rifle gun made for Piomingo – $53.33” (Figure 38).[7] This cost was unusually high—a typical rifle at the time sold for no more than about $13. Perhaps part of the remarkable cost can be explained by Simpson’s agreement to build the rifle quickly, but the price also probably indicates that the rifle was of much better quality than average, as is the rifle made for Gasper Mansker. It is interesting to note that Piomingo, Mansker, and William Whitley served side by side in the fall of 1794 on the Nickajack Expedition against the Chickamauga. It is quite possible that Piomingo was carrying his new rifle on the campaign.

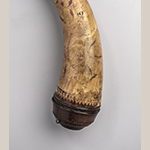

Like William Whitley’s rifle, the one Simpson made for Mansker has an accompanying powder horn (Figure 39). Uniquely designed, it is decorated with fine floral polychromed engraving that matches both the carved and engraved designs on Mansker’s rifle. It is obvious that Mansker’s horn, or others like it, inspired Jacob Young when he made Whitley’s horn (Fig. 21). The style of construction and turned butts of the two horns are very similar, each with a silver inlay surrounded with a turned cow horn decorative band (Figure 40). Simpson’s initials, “T.S.” are engraved on the butt of this horn, once again leaving little doubt that he was the maker (Figure 41).

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

Rifles built by Jacob Young and Thomas Simpson and the whereabouts of these gunsmiths have been controversial topics for the last several years. Jacob Young is a rather common name and as many as four different individuals sharing the name have been encountered while doing research. Genealogy reveals that the “gunmaker” married twice, thus separating him from the others. His first wife was Mary Boren, and they settled (by 1796) in Springfield, Robertson County, Tennessee. However, they divorced in 1808. Three years later, on 16 August 1811, Jacob purchased a 640-acre Revolutionary War Grant on Huchin’s Creek in Jackson County, Tennessee. He then married Mary (Polly) Huff and their first child, Jacob Young Jr., was born in 1813. This tract of property places Jacob Young within ten miles of Thomas Simpson’s mill near present-day Sparta, in White County, Tennessee. Goodspeed’s History of Tennessee for White County, states:

The Calf Killer Valley was the scene of the first settlements in the county, the neighborhood of what is now Sparta being in all probability the first, though Thomas Simpson settled on the Calf Killer River four miles below Sparta… .[8]

White County court minutes report that Simpson’s mill was built in 1808. In 1810, Simpson sold his Maddison Creek property in Sumner County, with the deed verifying that he had moved to White County, where he lived the rest of his life. Although his gravesite has not been located, a family account reports he is buried on the hill above the mill.

The name Thomas Simpson is also common and a second person with the name, who by 1790 had settled in Nelson County, Kentucky, creates some confusion. This Kentucky “Thomas” had a son named Jonathan, a well-documented nineteenth century Bardstown, Kentucky silversmith known for his high quality and extremely artistic surveying compasses (Figures 42 and 43). Genealogy has yet to prove a kinship between the Kentucky and Tennessee “Thomas Simpsons”; however, when studying the fine engraving style used on Jonathan Simpson’s compasses, it would be easy to assume a working relationship between Jonathan Simpson, Jacob Young, and/or Tennessee’s Thomas Simpson.

Another confusing issue is that the unique design elements described at the beginning of this article are also found on many rifles built two hundred miles away in the Bluegrass Region of Kentucky throughout the first half of the nineteenth century. It has been theorized that the work of Jacob Young and/or Thomas Simpson was the basis for these artistic commonalities, but recent research has revealed that William Bryan, (brother-in-law to Daniel Boone) the patriarch of one of Kentucky’s prominent gunbuilding families and his son Daniel, were also armorers and served alongside William Young and Thomas Simpson in the 1776 Cherokee campaigns (Figures 44, 45, and 46). Thus, a good case can be made that this artistic association goes back to the last quarter of the eighteenth century in North Carolina and was inspired by gun-building trends shared by William Young, Thomas Simpson, and William and Daniel Bryan.

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

The rifles made with extraordinary artistic merit by Jacob Young and Thomas Simpson stand as historic icons of the Cumberland, a misunderstood region that today is split in half by the boundary separating Kentucky and Tennessee. Pioneers such as William Waid Woodfork, William Whitley, and Gaspar Mansker, as well as Chickasaw Chief Piomingo, were critical to the settlement of the Cumberland and no doubt carried their rifles made by Young and Simpson with great pride.

The gunsmiths were integral to the development and evolution of the iconic Kentucky Rifle and provided an invaluable tool that enabled westward expansion of the United States of America.

Mel Stewart Hankla, Ed.D. is a researcher, speaker, and historical actor/educator focused on Kentucky’s heritage and an authority on Kentucky longrifles and powder horns. He is the founder of American Historic Services and can be reached at [email protected].

Bibliography

Pat Alderman, The Overmountain Men (Johnson City, TN: Overmountain Press, 1970).

John Allison, Dropped Stitches in Tennessee History (Nashville, TN: Marshall & Bruce, 1897).

Harriette Simpson Arnow, Seedtime on the Cumberland (New York: Macmillan, 1960).

James R. Atkinson, Splendid Land Splendid People (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama, 2004).

Lucy Forney Bittinger, The Germans in Colonial Times (Philadelphia, PA and London: F.B. Lippincott, 1901).

Marquis Boultinghouse, Silversmiths, Jewelers, Clock and Watch Makers of Kentucky 1785–1900 (Lexington, KY: Marquis Boutinghouse, 1980).

John Bradford, The Kentucky Gazette (Lexington, KY: John and Fielding Bradford, 1790).

Betty Huff Bryant, Building Neighborhoods: Jackson Co. Tenn. Early Land Records Prior to 1820 (Santa Maria, CA: Janaway, 1992).

Goldene Fillers Burgner, North Carolina Land Grants in Tennessee, 1778–1791 (Greenville, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1981).

Ruth Paul Burdette, The Long Hunters of Skin House Branch (Columbia, KY: Statesman Books, 1970).

Brenda C. Calloway, America’s First Western Frontier: East Tennessee (Johnson City, TN: Overmountain Press, 1989).

Paul Clements, Chroniclers of the Cumberland Settlements (n.p.: Paul Clements, 2012).

S. Cotterill, History of Pioneer Kentucky (Cincinnati. OH: Johnson & Hardin, 1917).

Everett Dick, The Dixie Frontier: A Social History of the Southern Frontier (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948).

Max Dixon, The Wataugans (Johnson City, TN: Overmountain Press, 1976).

Doug Drake, Jack Masters, and Bill Puryear, Founding of the Cumberland Settlements (Gallatin, TN: Warioto Press, 2009).

Lyman C. Draper, King’s Mountain and Its Heroes (Johnson City, TN: Overmountain Press, 1996).

Sherida K. Eddlemon, Tennessee Genealogical Records & Abstracts, Vol. 1 (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 1999).

Ellen Eslinger, Running Mad for Kentucky (Lexington: University of Kentucky, 2004).

Luther Evans, Putnam County, Tennessee Richard F. Cooke’s Survey or Plat Book 1826–1839 — W.P.A. Records (Signal Mountain, TN: Mountain Press, 1939).

Richard Carlton Fulcher, Census of the Cumberland Settlements Davidson, Sumner and Tennessee Counties (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing, 1987).

Emma Lila Fundaburk, Sun Circles and Human Hands (Luverne, AL: Emma Lila Fundaburk, 1957).

Westin A. Goodspeed, History of Tennessee: Middle Tennessee (Nashville, TN: Goodspeed Publishing, 1887).

Neal Hammon and Richard Taylor, Virginia’s Western War 1775–1786 (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole, 2002).

Mel S. Hankla, “Return to Manskers Station,” Muzzle Blasts, Vol. XLIX, No. 10 (June 1988).

Charles B. Heinemann and Gaius Marcus Brumbaugh, “First Census” of Kentucky, 1790 (Baltimore, MD: Southern Book Co., 1956).

Marjorie Hood Fischer, Tennessee Tidbits: 1778–1914, Vol. 1 (Easley, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1986).

Richard Carlton Fulcher, Census of the Cumberland Settlements 1770–1790 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing, 1987).

Irene M. Griffey, Earliest Tennessee Land Records & Earliest Tennessee Land History (Baltimore, MD: Clearfield, 2000).

John Haywood, The Civil and Political History of the State of Tennessee (Nashville, TN: Barbee & Smith, 1891).

Archibald Henderson, The Conquest of the Old Southwest (New York: Century, 1920).

Deborah Kelley Henderson, “It Is A Goodly Land” (Nashville, TN: Parthenon, 1982).

D. Lewis, NC Patriots 1775–1783: Their Own Words, Vol. 2, electronic publication (Little River, SC: J. D. Lewis, 2012).

Walter Lowrie, American State Papers, Vol. IV (Washington, DC: Gales and Seaton, 1832).

Anderson Chenault Quisenberry, Kentucky in the War of 1812 (Frankfort: Kentucky Historical Society, 1915).

J.G.M. Ramsey, The Annals of Tennessee (Kingsport, TN: Kingsport Press, 1967).

Theodore Roosevelt, The Winning of the West (New York: G.P. Putnam & Sons, 1889).

Bryon Sistler and Barbara Sistler, Early Tennessee Tax Lists (Santa Maria, CA: Janaway, 2006).

William S. Speer, Sketches of Prominent Tennesseans (Greenville, SC: Southern Historical Press, 1978).

Charles G. Talbert, A History of Colonel William Whitley (Louisville, KY: Filson Club, 1951).

Samuel Cole Williams, History of the Lost State of Franklin (Johnson City, TN: Watauga Press, 1924).

Gary Dean Young, Life and Times of William Young: Tennessee Frontiersman, Utah Pioneer, online: http://sites.rootsweb.com/~utwashin/history/wmyoung.html (accessed 4 January 2019).

[1] Harriette Simpson Arnow, Seedtime on the Cumberland (New York: Macmillan, 1960), 13–14.

[2] William S. Speer, Sketches of Prominent Tennesseans: Containing Biographies and Records of Many of the Families Who have Attained Prominence in Tennessee (Nashville, TN: Albert B. Tavel, 1888), 297.

[3] Ibid, 452.

[4] Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, Application for Joseph Luske, 1823, Publication Number M804, Roll 1602, Surname Range: Lupardus, William – Lutes, Henry, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15, National Archives, Washington, DC; available online by subscription: Ancestry.com, U.S., Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, 1800–1900, [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA. Surname Range: Lupardus, William – Lutes, Image 802.

[5] Paul Fink, “Some Phases of the History of the State of Franklin,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Vol. XVI, No. 3 (1957): 195.

[6] American State Papers: Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States (Washington, DC: Gales and Seaton, 1832), 466; available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=hbWsTT4Mdr0C&lpg=PA466&ots=WZ2oOUand-&dq=I%20want%20you%20to%20get%20Simson%20to%20make%20me%20a%20gun%20like%20Col.%20Mansker%E2%80%99s&pg=PA3#v=onepage&q=I%20want%20you%20to%20get%20Simson%20to%20make%20me%20a%20gun%20like%20Col.%20Mansker%E2%80%99s&f=false (accessed 4 January 2019).

[7] James R. Atkinson, comp., Records of the Old Southwest in the National Archives: Abstracts of Records of the Chickasaw Indian Agency and Related Documents, 1794–1841 (Starkville: Mississippi State University, Cobb Institute of Archaeology, 2005), 205–208.

[8] History of Tennessee from the Earliest Time to the Present: Together with an Historical and a Biographical Sketch of Cannon, Dekale, Warren, White Counties, besides a Valuable Fund of Notes, Original Observations, Reminiscences, Etc., Etc. (Nasvhille, TN: Goodspeed, 1887), 799.

© 2019 Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts