After serving his second term as President of the United States and returning to Monticello in 1809, Thomas Jefferson compiled a detailed inventory of artwork he owned and where it was displayed. In the dining room, beneath religious paintings and a still life, Jefferson listed landscapes that included a print of New Orleans, two views of Niagara Falls, an elevation of Monticello, and a view of Mount Vernon. In addition, he recorded two landscapes by a previously little-known Virginia-born artist William Roberts (1762–1809) listed as: “81. the Natural bridge of Virginia on Canvas by Mr. Roberts” and “82. the passage of the Patomak through the Blue ridge. do.”[1]

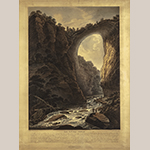

Roberts’s paintings of the Natural Bridge and Harper’s Ferry, views of two of Jefferson’s favorite places in America, were dispersed by sale along with all of the former President’s possessions after his death in 1826. It is unknown whether or not the paintings are extant. An aquatint of a view of the Natural Bridge made from Roberts’s original by the noted topographical artist Joseph Constantine Stadler (1780–1822) is held in the MESDA collection as well as an aquatint from Roberts’s “View on the Potomac, Virginia.” by Joseph Jeakes (1788–d.c.1829) (Figures 1 and 2).[2] A third aquatint, “Junction of the Potomac and Shenandoah, Virginia.” was also etched by Jeakes and is exhibited at the museum (Figure 3). Most significantly, MESDA owns two watercolor studies painted by Roberts in preparation to publish his engraving “Junction of the Potomac and Shenandoah, Virginia” (Figures 4 and 5). The two watercolors are the only examples of William Roberts’s original work known to survive.

Scholarship about William Roberts is nearly as rare as his surviving work. In her 1984 article, Barbara Batson published the first and only article about the artist, concisely placing his work within the picturesque tradition.[3] Roberts’s life, according to Batson, “remains largely obscure; the years of his birth and death, his training, even his nationality—all are unknown or uncertain.”[4] The recent discovery of a travel journal, which he called his “Manual of Locomotion,” kept by Roberts between 1770 and his death in 1809 provides a clearer and deeper understanding of his life and warrants building upon Batson’s work.[5] [6] This re-appraisal of Roberts’s work will further confirm his importance within the narrative of early American landscape painting through the artist’s efforts to fulfill Thomas Jefferson’s vision of the country’s natural monuments as subjects of serious artistic merit.

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

William Roberts was born in Portsmouth, Virginia in June 1762.[7] He was the second child and eldest son of Ann Eyre Mifflin Roberts (c.1733–1802) and Humphrey Roberts (d.c.1791).[8] His mother was a wealthy heiress from the Eastern Shore of Virginia and a member of both the Eyre and Mifflin families by marriage and by birth.[9] Orphaned at the age of five, Ann was raised by her Mifflin grandparents at Pharsalia in Accomack County, Virginia. When she was twenty, she married distant cousin George Mifflin Jr. (1725–c.1754) of Philadelphia.[10] Tragically, he died shortly after their marriage and birth of their only child Charles (1753-1783).[11] Humphrey Roberts, Ann’s second husband, was an English-born merchant who arrived in Norfolk, Virginia in 1755.[12] The couple married in 1759, and had four children: Ann Roberts Taylor (c.1760–1851), William (1762–c.1811), Edward (d.1816), and Mary Roberts Aitcheson (1775–1814).[13] Through his wife’s local connections, property, and fortune, Humphrey’s star rose quickly. He was a founding partner in the City of Portsmouth where he accumulated land both inside and outside the city, opened a store, and operated a successful mercantile operation until the war.[14]

In 1770, Humphrey and Ann Roberts sent their eldest son, William, to attend the elite Academy and College of Philadelphia.[15] William spent the majority of the next six years at the academy, where he received a liberal education alongside peers who came from elite and aspiring families from across the American colonies. In Philadelphia, he interacted with his Mifflin relatives and half-brother Charles.[16] Also in 1770, Humphrey Roberts signed the Association at Williamsburg, banning the import and export of British goods along with 150 other Norfolk-area merchants. At first the residents of Tidewater Virginia were fairly united in their goal to put pressure on Britain through embargo, but by early 1775 a crisis was looming between those who ardently supported the American cause and those who sought to maintain ties with England. Local merchants, including Humphrey Roberts, had the most to lose through independence and became targets for persecution.[17] Humphrey was implicated by his enslaved pilot Caesar for loyalist sympathies later in 1775 and was investigated by the Virginia Convention.[18] Choosing to side with England, Humphrey joined Lord Dunmore’s fleet in the Chesapeake Bay and fled to New York later that year.[19] His wife and children left Portsmouth for Northampton County on the Eastern Shore where Ann owned land called Golden Quarter.[20]

As the calendar turned to 1776, with his father in New York City seeking passage back to England and his mother and siblings finding haven on the Eastern Shore, William was still at school in Philadelphia, the very center of the Revolutionary storm. The trustees of the Academy and College of Philadelphia decided in June that the normally public commencement ceremonies for graduates would be private “on account of the present unsettled State of public affairs and the Candidates are accordingly to be excused from Delivering the public Exercises usual on such Occasions.”[21] William’s final departure from the academy was noted in the tuition account book: “William Roberts gone June 10th.”[22] The fourteen-year-old returned to Virginia, “his native Country” to rejoin his family but found them refugees “bereft of their all their Property, turnd [sic] out of their Habitations.”[23]

Virginia had passed a statute in 1775 lowering the age of eligibility for mandatory service in the militia. Making his choice to leave Virginia rather than fight the English, William traveled north on 6 December 1777, to Pharsalia the home of his uncle Daniel Mifflin in Accomack County, Virginia and from there to Kent County, Delaware and the home of his cousin Warner Mifflin, the famous Quaker abolitionist.[24] He made “three fruitless Attempts to get to Philadelphia when the British Troops were there” and was allegedly imprisoned for openly refusing to bear arms against the British.[25] William was finally able to make his escape to New York by way of the Caribbean, likely through one of his father’s mercantile connections.[26]

Father and son arrived in London on Christmas Day 1780. William came equipped with letters to recommend him to London society and to help verify his situation as a refugee of war which were helpful in his applications for compensation from the British Government.[27] An English officer stationed in New York, Lieutenant Cosmo Gordon, wrote to his brother William Gordon in London informing him about “Mr. William Roberts[,] a young man of respectable Character and promising Talents, he in the Hapless situation of many more is under the necessity to fly his Native Land, to seek Protection in the parent State, intended for the law he wishes to study in the Temple.”[28] Lt. Gordon requested that his brother introduce William to their uncle, Lord Adam Gordon, and use their family’s connections and influence to help him secure entrance to Middle Temple. Years later, William dedicated a play to Lord Gordon, writing that, “…since my arrival in this country, [he has shown me] the tenderness and attention of a father.”[29] With their help William was admitted to study law at Middle Temple on February 15th, 1781.[30]

Once admitted to Middle Temple, William continued to apply to the government for compensation as a Loyalist American.[31] As the eldest son of a Loyalist, he argued that the war had deprived him of his fortune and education. By 1783 William was in desperate straits and he appealed directly to one of the commissioners Daniel Parker Coke (1745-1825) of Inner Temple that the delay in receiving an allowance “involved me in the most Embarrassing Difficulties I have struggled through them with Patience till now that they have become to pressing and without your friendly Interposition, am exposed to Situations more distressing than you would be ready to conceive.”[32]

His father Humphrey finally returned to America around 1786 in an attempt to reverse his wife’s manumission of thirty slaves, which she was entitled to in her dowry.[33] He died shortly thereafter. In his 1788 will Humphrey left the majority of his holdings to his son Edward who took over the mercantile business in Portsmouth. He left William fifty pounds, noting that his eldest son had already spent his inheritance on his education.[34]

In May 18, 1787, William was called to the bar, or qualified to act as an official officer of the court, and settled in the Manchester area where he worked as a barrister.[35] In Manchester, he established a position for himself, serving as Steward of the Court of Leet, however, his temper and ambition caught up with him.[36] He entered into a nasty public feud with wealthy cotton merchant Thomas Walker that ended in a libel case that found Roberts guilty.[37] [38] To seal Roberts’ fate, Walker published the 288 page full-transcript of the trial, which painted a foul picture of the young barrister. Despite William’s attempts to repair his reputation, he resigned his post as steward and returned to London in February of 1792.[39]

His career and reputation in tatters and without a legacy to his name, Roberts turned to marriage for financial security. On 20 June 1793 he wed Elizabeth Galloway (c.1744–1815) (Figure 6), the daughter of Loyalists from Pennsylvania, Joseph Galloway (1731–1803) (Figure 7) and his wife Grace Growden (1733–1782).[40] Before the American Revolution, Joseph Galloway served as Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly and drafted a failed plan of union to prevent the colonies from leaving Britain before the war. He and his daughter Elizabeth fled to England in 1778.[41] The vast Galloway properties in Pennsylvania were confiscated during the war and her mother, Grace Growden Galloway, who remained in America in an attempt to protect their estates, died in poverty in 1782.[42] Roberts was acquainted with the family as early as 1780 when Joseph Galloway wrote a letter of recommendation in support of the young man’s claim for reparations and the families certainly had mutual connections in Philadelphia.[43]

Had it not been for the American Revolution, Elizabeth would have easily been heiress to one of Colonial America’s largest fortunes, which she fought desperately from England to reclaim after the war.[44] Roberts and his bride Elizabeth likely circulated in the same social circles of Loyalist refugees in Britain.[45] During their courtship Roberts published a play entitled “The Fugitives,” a comedy of errors which mimics their stories of being born in America, fleeing their homeland, and finding love in England.[46] Elizabeth herself was a prolific writer. She wrote poetry (both lyrical and narrative), romantic short stories, dialogues, and at least one play.[47]

However romantic and heady their courtship may have been, the marriage of William and Elizabeth Roberts was a troubled one. A letter from her father to relatives in America chronicled the start of the unhappy marriage alleging that only a few days into their honeymoon William grew violent and threatened Elizabeth’s life, threatening to “level her to dust.”[48] According to Galloway, the verbal threats turned to physical violence a number of times and the distressed Elizabeth miscarried shortly after their marriage. At first William’s stormy temper led Elizabeth to blame herself for her inability to curb her husband’s moods. In a poem written while they were still on their honeymoon, Elizabeth tried to explain her fears:

Trust me William did you sigh,

You might tempt me to comply,

But when you with passion storm,

And each gentle look transform,

I with horror view the scene,

And myself from danger screen;

Or when sullen you appear,

I retire in deep despair,

Hopeless to retain a heart,

Where ill humour holds a part.

Smile then William, smile and prove,

you can please, and I can love

— E.R. July 1793[49]

It was clearly a tragic and incompatible match. Over the course of their first year of marriage, William left her repeatedly, refusing to live with her, and Elizabeth continued to let him back, according to her father, “under the hope of reforming him and of his treating her better.”[50] Elizabeth became pregnant again but a month before she gave birth Roberts moved out of their home to lodge in Kentish Town and then Chelsea. He returned to Fitzroy Street the day before Elizabeth gave birth to their daughter, Grace Ann, named after both of the couple’s mothers. Roberts apparently lived with his wife and child for about another year, until May 1795, when he declared in his journal: “To Islington & parted from a wicked wife.”[51] A short while later he took their infant daughter away from her mother to reside with him at Saling Green in Essex, the estate of fellow Tidewater Virginia Loyalists the Goodriches.[52] [53]

According to his travel journal Roberts tried twice over the next few years to leave England with his daughter and return to Virginia.[54] In 1797, in his second attempt, Roberts and three-year-old Grace Ann boarded the ship The Martyr at Gravesend but they were blown back by a storm. In a twist worthy of one of her stories, Elizabeth somehow intercepted The Martyr and the three of them intended to sail for Virginia but their voyage was thwarted by another storm. The family disembarked the ship at Cornwall, where Roberts took advantage of the scenery by sketching. Famed topographical engraver and publisher Francis Jukes (1745–1812) produced two prints in 1799 of the town of Launceston after Roberts’s work (Figures 8 and 9).[55] The prints are the first indication that he sketched his travels with the intent of publishing.[56] They also reveal his interest in the picturesque genre.

For Elizabeth, the abduction of their child was the final straw and with the advice of friends and family, they agreed to a legal separation.[57] The passionate, intelligent, and independent young couple waged bitter warfare over a private separation agreement, which gave William a comfortable living but granted Elizabeth custody of their child.[58] He would never reside with his wife and child again and was only allowed limited visitation.[59] Joseph Galloway made every possible precaution in his 1803 will to completely exclude his son-in-law from his estate.[60] In her 1815 will, Elizabeth made provisions for their daughter Grace Ann to receive funds “for her own separate use independent of the Control or Management of her [Grace Ann’s] husband.”[61] Elizabeth appointed three men to look after Grace Ann and advise her in making a better choice for a husband than her mother had in Roberts. Two of the men appointed by Elizabeth, Elisha Hutchinson and Sir William Pepperell Sparhawk, were prominent Loyalist refugees.

With the separation agreement settled, Roberts finally succeeded in returning to Virginia in June 1799 where he was reunited with his beloved mother and siblings. It is unclear why he returned to Virginia at this time, but he had been attempting to return for the past several years. The following year Roberts took a trip to Pennsylvania to visit his daughter and his wife whom had also returned briefly to settle some of the vast Galloway estates in America, visiting family at Four Lane End.[62] He then made his way to New York where he stayed with John Ireland, minister of St. Ann’s Church in Brooklyn.[63]

In 1801 Roberts traveled with his mother and sister Ann (known as Nancy as not to be confused with her mother also named Ann) to visit relatives around Philadelphia and also went to Four Lane End where they undoubtedly called on Roberts’s daughter Grace Ann. A year later he was off again, this time taking a journey by ship to Baltimore and from thence to New York City. In May 1802 he took a trip up the Hudson Valley to Kinderhook, Schenectady, and Albany and back.[64] Upon his return downriver to New York City, Roberts learned of the death of his mother. By the time the news reached him, she had been deceased almost a month. He penned one of the longest entries in his otherwise concise travel journal: “May the sensation I felt enlighten me for the rest of my Life.”[65] Roberts hastened back to Norfolk to visit his mother’s grave at Trinity Church. As the family settled her affairs, he planned his final adventure in Virginia: a summer sightseeing trip with his sister Nancy.[66] In his journal Roberts titled the trip an “Excursion over the mountains.”[67]

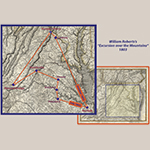

On 10 July 1803, Roberts and his sister set off from Norfolk by way of the James River, through Petersburg and north to Richmond (Figure 10). They passed through Hanover courthouse to Charlottesville where they made their first major stop at Monticello. In a letter written 24 July 1803, Roberts reminded President Jefferson that they had been introduced nearly twenty years prior in London by J. Hector St. John Crèvecœur (1735–1813), author of Letters from an American Farmer (1782).[68] The siblings were invited to dine with the President at Monticello and talk during the meal undoubtedly centered on the course of their excursion, which would take them to some of Jefferson’s favorite places in Virginia.

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

By the time William Roberts visited in 1803, the Natural Bridge was indelibly linked with Thomas Jefferson. In Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson wrote of the bridge: “It is impossible for the emotions, arising from the sublime, to be felt beyond what they are here: so beautiful an arch, so elevated, so light, and springing, as it were, up to heaven, the rapture of the Spectator is really indescribable!”[69] Jefferson had first visited the Natural Bridge in 1767 and was so enthralled that seven years later in 1774 he purchased the Bridge and the surrounding 178 acres.

Newspapers and periodicals regularly reprinted excerpts from Notes on the State of Virginia, especially those describing the bridge. These accounts had an enormous impact on the landmark’s popularity as a destination. By the time Roberts visited the bridge it was already a destination for curious, literary tourists who dared risk the discomfort of the sometimes-rugged journey to reach the bridge. Wife of Scottish diplomat Henrietta Liston wrote that her husband left their guide with a copy of Jefferson’s book, noting that, “that the person who shewed the Bridge to strangers ought to be inabled [sic] to give the most perfect account of it… .”[70] Thomas Jefferson’s imprint on the Bridge’s legacy is inextricable even today.

Put simply, for Jefferson the Natural Bridge captured both the beauty and terror embodied by the picturesque movement. It was the ideal sublime landscape. The picturesque was a highly theorized aesthetic developed in the late eighteenth century by writers such as William Gilpin (1724–1804), Uvedale Price (c.1747–1829), and Richard Payne Knight (1751–1824).[71] By the turn of the nineteenth century, the depiction of landscapes by artists was the subject of fervent cultural discourse. At one extreme was the sublime (characterized as rough, wild, and awe inspiring) and at the other the beautiful (smooth, refined, and pretty). Mediating the sublime and beautiful was the picturesque (containing elements both sublime and beautiful). Gilpin espoused that the picturesque was “a term expressive of that peculiar kind of beauty, which is agreeable in a picture.”[72] Applied to landscape painting it was the job of the informed artist to render the view in a pleasing way that elicited both fear and intrigue, while capturing nature’s inherent beauty (Figure 11).

An English clergyman, William Gilpin espoused his idea of the picturesque for a wide audience through his accounts of his tours through England and Wales. Tantamount to prescriptive literature for educated tourists to aestheticize their traveling experiences, Gilpin’s travel narratives inspired members of England’s middling classes to take advantage of an ever more accessible English countryside. His most lasting contribution to the picturesque landscape was that travelers and spectators should be active participants in their viewing of landscapes and use their imaginations to modify the scenes around them accordingly.[73]

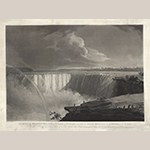

The genre of landscape painting and its impetus in early America have been discussed by many authors, with substantial emphasis on the development of the Hudson River School.[74] [75] American artists and travelers sought to define and celebrate the identity of their new country through its natural landmarks while curiosity propelled Europeans to explore and produce their own narratives. These people were not explorers, but tourists who favored well-trodden destinations such as Niagara Falls and the Hudson River (Figure 12).[76] Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia, first English-language publication in 1787, has long been viewed as a promotional tract for the state. Jefferson decried Virginians for their lack of interest in their landmarks. He wrote of his countryman’s indifference:

Yet here [Harper’s Ferry], as in the neighborhood of the natural bridge, are people who have passed their lives within half a dozen miles, and have never been to survey these monuments of war between rivers and mountains, which must have shaken the earth itself to its core.[77]

Jefferson desired Virginians not to just exist in this landscape, but to cultivate the knowledge required to appreciate and experience it in enlightened ways.

For Jefferson these places were spaces of passion and physical feeling. Places of seduction. He wrote desirously to English artist and love interest Maria Cosway in 1786, “I will believe you intend to go to America, to draw the Natural bridge, the Peaks of Otter &c., that I shall meet you there, and visit with you all those grand scenes.”[78] He flirtatiously teased fellow American expatriate Angelica Schuyler Church that, “While you are indulging with your friends on the Hudson, I will go to see if Monticello remains in the same place. Or I will attend you to the falls of Niagara, if you will go on with me to the passage of the Patowmac, the Natural bridge &c.”[79]

Jefferson tried to position American landscapes as ancient monuments, akin to the ruins of Ancient Greece and Rome (Figure 13). He saw monuments like the Natural Bridge as signs of America’s inherent civilization.[80] Travels in England compelled Jefferson to both decorate his household with views of American landscapes and to encourage artists to consider landmarks like Niagara Falls and the Natural Bridge as subjects of serious artistic merit. Anna Marley writes that this “suggests that seeing the art and landscapes of the great houses of England provoked thoughts in his [Jefferson’s] mind about how the American landscape would be treated by artists and deployed in a similar way to those Italianate Grand Tour landscapes that were in British domestic interiors.”[81]

Beyond his suggestion to Maria Cosway that she depict the Natural Bridge, there is more evidence Jefferson desired American artists to take on the challenge of representing these monuments. In 1791, Jefferson suggested to American-born artist John Trumbull that he represent the Natural Bridge while he passed through Virginia. Jefferson urged Trumbull to do “…yourself and your country the honor of presenting to the world this singular landscape, which otherwise some bungling European will misrepresent.” Trumbull did not oblige the statesman, and left it to the bungling Europeans.[82] In 1786, Frenchman François-Jean Chastellux published in his American travel narrative two crude views of the Natural Bridge inexpertly drawn by one of Rochambeau’s engineers.[83] (Figures 14 and 15). Variations of this engraving were emulated, like one used to illustrate the third American edition of Notes on the State of Virginia, published in New York in 1801 (Figure 16).[84] Irishman Isaac Weld, published a more conventional, picturesque view of the bridge in his 1800 travel narrative of his trip through America (Figure 17).[85] But these were only book illustrations. Jefferson clearly wanted monumental works of art to celebrate these natural landmarks as fundamental to America’s identity.

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

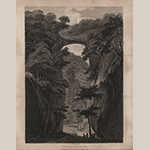

William Roberts and his sister Nancy were clearly enthralled with the Natural Bridge. They spent two days at the site, likely experiencing the natural monument with all of the awe and passion Jefferson hoped they would find. In the absence of Roberts’s study sketches or an oil painting of the Natural Bridge, the aquatint etched by Joseph Constantine Stadler must stand as a substitute in order to convey the artist’s encounter with the bridge.

In the lower margin of the print is a passage from Notes on the State of Virginia that describes the sublimity of the arch (Figure 18). By adding Jefferson’s text to the print Roberts was doing something very important: he was associating the narrative with a place and the place with a person. All who traveled to the Natural Bridge had Jefferson’s words in mind when they experienced the arch. Perhaps as significant, Roberts then added his own perspective of the landscape, recording his observations and explicitly pointing out areas where he used the artistic license of a picturesque artist. He noted:

The above View was taken from the spot where it is usually and to the most advantage beheld by its Visitors, but the point of sight being so near an object so elevated the receding lines of the perspective so rapidly decline as to give an appearance of the ascent of the Bridge being reversed.

The limestone bridge rises monumentally above tiny figures as Cedar Creek gushes its way towards the James River. According to Roberts, the area had experienced summer rainstorms and the stream “at the time of the Drawing had been swol’n” to a “torrent, not always seen.” In order to emphasize the sublimity of the arch, Roberts used artistic license to remove “two or three Trees on the Peninsula beneath the Arch, which as they obstructed the view of the back ground… .” The figures depicted beneath the bridge are travelers and tourists. Venturing out to a large boulder, two men in the foreground actively engage with the scene—reacting in awe to the sublimity of the bridge. The two men standing and woman seated nearer to the bridge itself appear to be resting from a walk, contemplating the beauty of the wilderness.[86] Roberts is clearly comfortable with the picturesque as an aesthetic as well as in practice.

Roberts’s education as an artist is not clear, although he would most certainly have been trained in perspective drawing, surveying, and draftsmanship as part of the curriculum at the Academy and College of Philadelphia. It is possible that he may not have even considered himself a professional artist; with his wife’s fortune he had adequate means to support a lifestyle of travel and leisure without toiling at an easel. Regardless, not only did Roberts possess the knowledge to participate in the culture of picturesque tourism, he was clearly adept at creating images that embodied the picturesque aesthetic. Given the intensity of his interest in picturesque travel, his familiarity with cultivated and aestheticized landscapes, and his literary aspirations, it is possible that he intended to someday publish an illustrated narrative account of his travels in the manner of Isaac Weld (1800) or perhaps to complete a series of engravings like General George Buteel Fisher whose six views of North America were published in a folio format by J.W. Edy in 1795.[87] Roberts’s intent to publish a written record of his own travels may have been precluded by his untimely death.

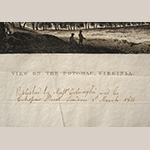

Further evidence for Roberts’s adherence to the picturesque are can be found in his depictions of Harper’s Ferry, the next destination on the “Excursion over the mountains.” Leaving the Natural Bridge, the siblings made their way north up the Great Wagon Road. Nearing the intersection of the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers, they followed the Elk Branch southeast to take in their first view of the Potomac, overlooking a bend in the river. Neither Roberts’s sketches nor his painting of this scene survive; however, an aquatint of the view etched from Roberts’s original does survive, titled “View on the Potomac, Virginia” (Fig. 2).

The “View on the Potomac” features several figures in the foreground looking out at the river with Maryland Heights and Loudon Heights in the distance. A bateau carrying goods navigates the shallow and rocky waters of the Potomac as it makes its way downstream—except it is actually traveling upstream. Joseph Jeakes made a mistake when etching the plate and caused the Potomac to flow backwards.[88] When the image is reversed the view correctly looks southeast downriver towards Harper’s Ferry and the juncture of the Shenandoah and Potomac. Perhaps the confusion arose from the fact that the Shenandoah River flows north towards Harper’s Ferry where it meets the Potomac.

Roberts and his sister made their way from their overlook of the Potomac towards Camp Hill, the area overlooking the town of Harper’s Ferry and the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers. Here Roberts stopped and sketched again, capturing the rivers, just as Jefferson described, “in the moment of their junction, [as] they rush together against the mountain, rend itself asunder, and pass off to sea.”[89] Roberts visually paraphrases Jefferson’s impression of the landscape, “inviting you, as it were, from the riot and tumult roaring around, to pass through the breach and participate of the calm below.” The artist’s picturesque ideal, with the violence of roiling water in the foreground contrasted by the inviting vista beyond, can be seen in his original watercolor sketches at MESDA (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5) and the resulting Jeakes aquatint “Junction of the Potomac and Shenadoah, Virginia” (Fig. 3).

In creating the watercolor studies for “Junction of the Potomac and Shenadoah” Roberts is following a progression that falls closely within Gilpin’s framework whereby the artist improved nature to make a resulting image more attractive. A landscape, Gilpin writes, “may in reality be awkwardly introduced,” but through the artist “may be altered, softened, and rendered pleasing.”[90] Harper’s Ferry at the time of Roberts’s visit was already a setting of industry and transit set amidst a rugged, deforested hillside. Little would have changed sixty-two years later when Alexander Gardner took a photograph from roughly the same spot (Figure 19).

While Roberts accurately represented the wild rivers and the sense of expansiveness in this first study (Fig. 4), but in order to create a picturesque composition he made significant changes to the second watercolor created in preparation for the aquatint (Fig. 5).[91] The progression from first study to final print can be followed in Figure 20. He added a quintessential tree to the left foreground, reduced the vertigo-inducing perspective of the rocky mountain faces, and softened the stark details. The resulting impression, seen in both the second watercolor study and the Jeakes aquatint, is of a softened, pleasant landscape, very different than the rocky and realistic first study (Fig. 4).[92] Industry and progress appear ordered but modern. The boats, likely crewed by enslaved people, blurred to the distance and in the foreground the ferryman actively working rather than lazing ashore. There appears to be no danger in the final image other than the sheer expanse and scale of America’s wilderness. Roberts had consciously infused fundamental elements of the picturesque into his view of Harper’s Ferry by tempering the sublime wilderness with a refined beauty.

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

After Harper’s Ferry, Roberts and his sister journeyed towards Leesburg, Virginia and ultimately arrived home in Norfolk on 3 October 1803. The sibling’s tour took four months to complete. By Roberts’s reckoning they travelled 843 miles. While he remained in the Norfolk through the winter, the “Excursion over the mountains” was akin to a farewell tour of Virginia for Roberts.[93] The death of his mother seems to have ended all ties with “his native country,” and he most likely spent the remainder of his time there settling his mother’s affairs and making at least two oil paintings from his sketches of the Natural Bridge and Harper’s Ferry.

By July 1804, Roberts had arrived in Washington, DC where he hand delivered two landscapes in oil for President Jefferson to the Executive Mansion. In a letter accompanying the paintings that he left for Jefferson, Roberts wrote that he had “amused himself with taking various drawings of the Scenery through which he passed.” He made sure to note, “Two of these Views being, he believes, favourites of Mr. Jefferson.”[94] Before moving on to the New York City area, Roberts sat to have his portrait painted by Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828) (Figure 21). According to his journal, Roberts remained in New York until August 1806 when he sailed for England.[95]

Upon his return, he began publishing his views of America. On February 27, 1808, the firm of P.D. Colnaghi and Co. on Cockspur Street who published an aquatint of the Natural Bridge etched by John Constantine Stadler. The print was much acclaimed in April of that same year by The Monthly Magazine, where it was called an “exceedingly beautiful and picturesque print.” They raved, “The superior effect given by the grand productions of nature, to the feeble imitations of art, has been often described by good writers, but oftener felt by every man of genuine and unvitiated taste; but we never saw it exemplified in a manner that struck us more forcibly, than in an exceedingly beautiful and picturesque print… .”[96] Though a critical success, the print does not to have been a commercial one. In May 1808, an advertisement informed the public that it was their last chance to obtain a copy before the remaining copies were sent to America.[97]

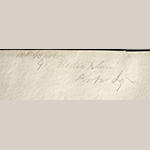

That same year, and perhaps at the same time as he deposited original artwork of the Natural Bridge, Roberts either engaged Jeakes to create plates from his views of Harper’s Ferry or deposited his watercolors with the printmakers P. D. Colnaghi & Co. on Cockspur Street and the firm arranged Jeakes to etch the plates. The paper upon which he painted his two watercolor studies of “Junction of the Potomac and Shenandoah” feature a watermark that reads “J WHATMAN / 1808,” as does the paper for surviving Roberts aquatints (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, and Fig. 22). Manuscript notes on MESDA’s copy of Jeakes’s aquatint “View on the Potomac” (Fig. 2) and a copy of “Junction of the Potomac and Shenandoah, Virginia” at the New York Public Library (Figure 22) establish both that the former was published a year after Roberts’s death in 1809 and a shared provenance for the prints. Along the lower margin of the “View on the Potomac” aquatint at MESDA is a handwritten statement that the print was published by “Mssrs. Conalghi” (Colnaghi & Co.) on Cockspur Street, London in 1810 (Figure 23). An inscription on the back of MESDA’s “View on the Potomac,” provides more provenance: “Mr. Burton / 91 Gloster Place / Portman Square” (Figure 24). The New York Public Library’s copy of “Junction of the Potomac and Shenandoah” bears a similar inscription: “Original picture in oils at 91 Gloucester Place. Painted by Mr. Roberts, father of Mrs. Grace Burton, Mother of Sir Charles Burton” (not illustrated).[98]

The significance of ownership of the prints by the Burton family at 91 Gloucester Place, as well as an original Roberts oil painting of Harper’s Ferry, is revealed through the marriage of the artist’s daughter, Grace Ann, to Benjamin Burton. The Burtons resided at 91 Gloucester Place and their children included a son, Sir Charles (Fifth Baronet of Ireland), and a daughter, Adelaide Burton, who was living at the same address as late as 1901. Thus William Roberts’s daughter and grandchildren preserved his artistic legacy into the twentieth century.[99]

In February 1808, William Roberts sent a letter and “a square flatt box” to Thomas Jefferson by way of the ship The Rolls.[100] The box contained fifty-two impressions the Natural Bridge, published 27 February 1808 according to a handwritten note along the bottom margin of MESDA’s aquatint (Figure 25). Arriving in Virginia at the Richmond Collector’s Office in June, the box was received by James Gibbon, the duty collector, who wrote to Jefferson inquiring if the President had an invoice so that duties could be calculated on its contents. Based on the “form & size of the Box,” Gibbon thought, “it contains Mapps or prints… .”[101] In Roberts’s letter, which Gibbon forwarded separately to Jefferson, the artist offered Jefferson the opportunity to pick two of the best impressions, and stated he was:

desirous that you should possess an accurate representation from my original drawing. as the paintings you before received [sic], were not I think altogether so worthy of the Subjects.[102]

After some confusion regarding the contents of the box in Richmond, Jefferson made the connection between Roberts’s letter and the prints.[103] In his letter, Roberts requested that after the President had selected the two best impressions, the remaining aquatints be forwarded to his brother Edward Roberts so that they could be sold in Norfolk. Obligingly, Jefferson requested that George Jefferson, his cousin and agent in Richmond, “take out 2. of the prints, forward one of them to Monticello, accept the other yourself, and forward the residue to mr Edward Roberts of Norfolk… .”[104]

In addition to the oil paintings presented in 1806, Roberts was rather obviously ingratiating himself to Jefferson by including the description of the bridge from Notes on the State of Virginia and offering him the best two impressions of the aquatint. Perhaps Roberts could not resist yet another attempt to solidify his association with the President and Jefferson’s hopes that America’s natural monuments become canonized through art. Closing his letter, Roberts reminded Jefferson of their shared birthplace, writing that his picturesque image of the Natural Bridge was “from the pencil of a Virginian.”[105]

Roberts’s love of travel and sketching landscapes might have led to his death. On 15 July 1809, two years after publication of the Natural Bridge aquatint, in one of the last entries in his travel journal, Roberts recorded that he had written a letter to his sister Nancy informing her of his impending trip through Wales. Eight days later a Manchester newspaper reported, on 23 July 1809, that “William Roberts, barrister at law” had passed away in Aberystwyth, a well-known final stop for artists touring North Wales.[106] A North Wales travelogue by the best-known theorist of the picturesque, William Gilpin, had been posthumously published only months before Roberts’s own demise.[107]

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

Whether Roberts considered himself a professional artist or rather an educated tourist may never be determined. Regardless, his aptitude as a picturesque traveler is apparent. Publication of his views of the Natural Bridge and Harper’s Ferry, etched by two well-known engravers of the genre in London, suggest an artist with professional aspirations. His unexpected death may have prevented any plans Roberts had for publishing his travel journal, but such a step would have been consistent with his contemporaries working in the picturesque.

Although not a prolific artist, William Roberts must be considered a noteworthy contributor to early America’s landscape painting tradition. Evaluating his surviving work, travel journal, and correspondence clearly establishes his fervent wish to be associated with Thomas Jefferson and further the President’s ambition to promote America’s inherent identity through its natural monuments. Roberts’s views of the Natural Bridge and confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers at Harper’s Ferry fulfilled a particular goal for both the artist and Jefferson.

Katie McKinney is the assistant curator of maps and prints at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. She can be contacted at [email protected].

[1] Thomas Jefferson, “Catalogue of Paintings &c. at Monticello,” Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, Acc. 2958-b, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA; available online: https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/catalogue-paintings (accessed 3 August 2018).

[2] Aquatint is an intaglio printmaking technique used to create tonal effects rather than lines and results in prints to resemble watercolors or ink washes. The technique was developed in France in the 1760s and became popular in Britain in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It is often used in combination with other intaglio techniques. “Aquatint,” Tate Art Terms, online: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/aquatint (accessed 16 August 2018).

[3] Barbara C. Batson, “Virginia Landscapes by William Roberts,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Vol. X, No. 2 (November 1984): 34–48; available online: https://archive.org/details/journalofearlyso1021984muse (accessed 16 August 2018).

[4] Ibid, 35.

[5] The journal is cataloged in the artist’s father-in-law’s papers with the misleading title “Joseph Galloway Travel Notebook.” Roberts recorded the date and location for events in his life from 1770-1809. The journal also includes a letter book for letters sent after 1807. William Roberts, “Joseph Galloway Travel Notebook” (Travel Journal of William Roberts), 1770–1809, p. 1, Folder AC 14, 080, Library of Congress, Manuscripts Division, 10 and 11 .1.; Pages covering 1804–1805 of the journal are located at the University of Wisconsin: “Item 68 Mileage record book 1804-05 in the hand of William Roberts,” Reel 1, Cairns Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, University of Wisconsin Libraries, Madison, WI.

[6] Independent of this author’s research, the William Roberts travel journal was also identified in the Library of Congress by noted historian and author Gary B. Nash. The author is grateful for his assistance in unraveling the complex mysteries of the Roberts family and for pointing out the presence of Roberts and Galloway family documents in various collections. The Roberts, family is discussed at length in Nash’s excellent book Warner Mifflin: Unflinching Quaker Abolitionist (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2017).

[7] A mutilated inscription at the beginning of his travel journal reads, “Wm Roberts was born June [illegible] 1762 in Portsmouth/ Virginia.” “Joseph Galloway Travel Notebook” (Travel Journal of William Roberts), 1770–1808, p. 1, Folder AC 14, 080, Library of Congress, Manuscripts Division, 10 and 11.1.

[8] “Will of Humphrey Roberts,” written 24 November 1788, proved in Norfolk 19 December 1791, and submitted in England 30 April 1793. See Norfolk County Will Book No. 3, 1788-1802, microfilm reel 49, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA and Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions, Will Registers, Class: PROB 11, Piece: 1231, pp. 268–269, The National Archives, Kew, England, cited from England & Wales, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384-1858, Will Register 1793–1795, available online by subscription: https://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=5111 (accessed 16 August 2018).

[9] Ann was the daughter of Neech Eyre and Ann Mifflin who were married in Northampton County, Virginia on March 12th 1732. Ann’s mother died in childbirth and her father remarried Isabell Harmonson in 1734. Shortly thereafter, Neech died, leaving Ann a young orphan at five years old. She was raised at Pharsalia in Accomack County by her Mifflin grandparents. To learn more about Ann Eyre Mifflin Roberts and her cousin Warner Mifflin, see Gary Nash’s detailed description of her fascinating life and her involvement with abolitionism in Warner Mifflin: Unflinching Quaker Abolitionist, 110-119.

[10] George and Ann were distant cousins, related through their Mifflin grandparents. Their marriage was advised against by both family and friends, which prevented their marriage to take place in the Quaker faith, which required the approval of the meeting community. The young couple chose to ignore the condemnations and were married by an Anglican priest at Christ Church on January 25, 1753. After they refused to condemn their own actions and despite the pleas of their relations, the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting disowned the couple on August 24th, 1753. George Mifflin and Anne Eyre, 25 January 1753, Pennsylvania, Church Marriages, 1682–1976, online: https://www.familysearch.org/search/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2WF-PW98 (accessed 16 August 2018). 270; 272-274. Minutes of the Philadelphia Monthly Meeting 1740-1755, Ancestry.com; For the disownment see, George Mifflin and Ann – Haverford College; Haverford, Pennsylvania; Minutes, 1740-1755; Collection: Philadelphia Yearly Meeting Minutes, Title: Minutes, 1740-1755, U.S., Quaker Meeting Records, 1681-1935 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Swarthmore, Quaker Meeting Records. Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania.North Carolina Yearly Meeting Minutes. Hege Friends Historical Library, Guilford College, Greensboro, North Carolina.Indiana Yearly Meeting Minutes. Earlham College Friends Collection & College Archives, Richmond, Indiana.Haverford, Quaker Meeting Records. Haverford College, Haverford, Pennsylvania.

[11] Charles Mifflin was the only child of George Mifflin II and Ann Eyre Mifflin Roberts. Ann returned to the Eastern Shore and left Charles to live with his Mifflin grandparents in Philadelphia. Upon the death of his grandfather, Charles was apprenticed to Thomas Wharton. Nash, 110; see also Rob S. Cox, “Finding Aid for Mifflin Family Papers, 1689–1877,” June 1994, Manuscripts Division, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan (available online: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/clementsmss/umich-wcl-M-2722.1mif?view=text [accessed 22 December 2018]).

[12] Humphrey Roberts noted in his Loyalist claim that he had been a resident of Virginia “upwards of 20 years” at the “early part of the Late troubles.” In the evidence portion of his claim, he stated that he was “A Native of England went to America in 1755 with a Cargo of Goods.” American Loyalist Claims, Series I, pp. 231 and 234, Class AO 12, Piece: 054, The National Archives of the UK, Kew, Surrey, England; cited in UK, American Loyalist Claims, 1776-1835, Series I, Piece 054, Evidence, Virginia, 1783–1786, images 132 and 134, available online by subscription: https://search.ancestry.ca/search/db.aspx?dbid=3712 (accessed 16 August 2018).

[13] Jordan R. Dodd, et al., Early American Marriages: Virginia to 1850 (Bountiful, UT: Precision Indexing Publishers, n.d.) cited in Virginia, Compiled Marriages, 1740–1850, 23 January 1759, available online by subscription: https://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=3723 (accessed 16 August 2018); see also “Will of Humphrey Roberts.”

[14] “Memorial of Humphrey Roberts,” American Loyalist Claims, Series II, p. 565, Class AO 12-13, Piece: 032, The National Archives of the UK, Kew, Surrey, England; cited in UK, American Loyalist Claims, 1776-1835, Series II, Piece 134, Claims C, Calderhead OPR, South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, image 836, available online by subscription: https://search.ancestry.ca/search/db.aspx?dbid=3712 (accessed 16 August 2018).

[15] The Philadelphia Academy was founded in 1751 to provide a liberal education for young American men. William Roberts entrance fee of 1 pound was paid on 15 August 1770. Thomas Willing, “Tuition Account Book, July 17, 1767–October 1, 1779; July 1, 1789–April 12, 1791,” p. 45, Archives General Collection, 1740–1820. UPA3 D1560, University of Pennsylvania Libraries, Philadelphia, PA; available online: http://sceti.library.upenn.edu/sceti/codex/public/PageLevel/index.cfm?option=image&WorkID=913 (accessed 16 August 2018).

[16] William noted that he had visited Philadelphia twice before 1770 when he started school. Roberts, Travel Journal, 1.

[17] For more on Norfolk Loyalists, see Adele Hast, Loyalism in Revolutionary Virginia: The Norfolk Area and the Eastern Shore (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1982).

[18] A letter from Thomas Pierce and Thomas Smith to the President of the Virginia Convention mentioned “Humphrey Roberts of Portsmouth noted Tory had removed his family there [the Eastern Shore].” Caesar, an “Excellent pilot” and man enslaved by the Roberts family was held captive by was their source for Humphrey’s movements and his political affiliations. See Robert L. Scribner and Brent Tarter, Revolutionary Virginia (Vol. 5): The Clash of Arms and the Fourth Convention, 1775–1776, 170 and 175.

[19] “Memorial of Humphrey Roberts,” 565.

[20] Humphrey Roberts quotes a December 1779 letter from Ann about the family’s dire situation on the Eastern Shore. American Loyalist Claims, Series I, pp. 231, Class AO 12, Piece: 054, The National Archives of the UK, Kew, Surrey, England; cited in UK, American Loyalist Claims, 1776-1835, Series I, Piece 054, Evidence, Virginia, 1783–1786, image 132, available online by subscription: https://search.ancestry.ca/search/db.aspx?dbid=3712 (accessed 16 August 2018).

[21] William Smith, Joseph Hopkinson, and Plunket Fleeson Glentworth, “Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania Minute Books,” Vol. 2 (1768–1779; 1789–1791), p. 97, UPA 1.1 University of Pennsylvania Libraries, Philadelphia, PA; available online: http://hdl.library.upenn.edu/1017.4/11134 (accessed 18 August 2018).

[22] Willing, “Tuition Account Book,” 134.

[23] Roberts, “Travel Journal” and “Memorial of William Roberts of the Town of Portsmouth Virginia,” American Loyalist Claims, Series II, p. 415, Class AO 12-13, Piece 032, Claims K-W Virginia, The National Archives of the UK, Kew, Surrey, England; cited in UK, American Loyalist Claims, 1776-1835, Series II, Piece 032, Claims K-W Virginia, image 552, available online by subscription: https://search.ancestry.ca/search/db.aspx?dbid=3712 (accessed 16 August 2018).

[24] Nash, Warner Mifflin.

[25] “Memorial of William Roberts,” 415.

[26] Roberts, Travel Journal, 1.

[27] “Memorial of William Roberts,” 415.

[28] “Evidence Cosmo Gordon to William Gordon, 10 October 1780, New York City,” Series II, p. 412, Class AO 12-13, Piece 032, Claims K-W Virginia, The National Archives of the UK, Kew, Surrey, England; cited in UK, American Loyalist Claims, 1776-1835, Series II, Piece 032, Claims K-W Virginia, image 549, available online by subscription: https://search.ancestry.ca/search/db.aspx?dbid=3712 (accessed 16 August 2018).

[29] William Roberts, The Fugitives: A Comedy (Warrington, England: Printed by W. Eyres, for John Stockdale Opposite Burlington House, Piccadilly London, 1791), iv.

[30] Middle Temple (London, England), and H. A. C. Sturgess.. Register of Admissions to the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, from the Fifteenth Century to the Year 1944, Vol. 2 (London: Published for the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple by Butterworth, 1949), 390.

[31] William’s entreaties for reparations lasted from 1780-1786. “Memorial of William Roberts,” 415.

[32] Ibid, 420.

[33] Humphrey Roberts’s exact date of departure from England is unknown, but it estimated to have been sometime between 1785 and 1786. In 1782, Ann freed the thirty slaves that were entitled to her through her dowry, which as Nash states, was done under the influence of her cousin Warner Mifflin. When Humphrey returned to the area he challenged the legitimacy of his wife’s actions and attempted to round up and re-enslave the manumitted individuals—capturing two and deeding one of them to his son Edward. A court case ensued which was litigated by St. George Tucker. For more on this incredibly interesting case see Nash, Warner Mifflin, pp. 117–119 and Christopher Doyle, “Judge St. George Tucker and the Case of Tom V. Roberts. Blunting the Revolutions Radicalism from Virginia’s District Courts,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 106, No. 4 (Autumn 1998), 419–442.

[34] William never mentions his father in his travel journal unlike numerous mentions of his sister Ann and his mother. “Will of Humphrey Roberts,” Prerogative Court of Canterbury…, 268.

[35] Middle Temple (London, England), and H. A. C. Sturgess, Register of admissions to the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, from the fifteenth century to the year 1944, Vol. 2 (London: Published for the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple by Butterworth, 1949), 390.

[36] He published one of his orations in 1793; see William Roberts, A Charge to the Grand Jury of the Court Leet for the Manor of Manchester, containing an Account of the internal Government of the Town; and of the Nature, Jurisdiction, and Duties of Courts Leets in general. Delivered at the Michaelmas Court, Oct. 15, 1788 (London: Butterworth, 1793).

[37] Thomas Walker (1749-1817) was a cotton merchant, political reformer, and abolitionist. For more on Walker, see John Barrell, Imagining the King’s Death: Figurative Treason, Fantasies of Regicide, 1793-1796 (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2006), Chapter 5.

[38] The libel case was a result of a disagreement that occurred on 5 November 1791 at a political dinner celebrating the “Glorious Revolution.” Roberts, a Tory, opposed a song (“Billy Pitt the Tory”) that was proposed by a Whig member of the assembly. When Roberts appealed to prominent cotton merchant and Boroughreeve Thomas Walker, who was presiding over the meeting, Walker refused action and Roberts vowed public retribution. Years earlier, Walker had very publically and successfully opposed Pitt’s controversial Cotton Taxes. The two men published letters challenging one another’s reputation in newspapers until Roberts published a posting-paper that insulted Walker outright. For the full transcript of the trial as published by Thomas Walker, The Whole Proceedings on the Trial of an action brought by Thomas Walker, against William Roberts, for a libel. Tried by a special jury … at Lancaster, March 28, 1791, before Sir Alexander Thomson (1791).

[39] Manchester Mercury and Harrop’s General Advertiser (Manchester, England), 1 January 1793, 4. For Roberts’ rebuttal, which was intended to be attached to Walker’s version, see: Roberts, William. 1791. The Whole Proceedings on the trial of an action brought by T. Walker … against W. Roberts … for a libel. Tried … March 28th, 1791 … Taken in shorthand by J. Gurney.

[40] Marriage of William Roberts and Elizabeth Galloway, 20 June 1793, Old Church, Saint Pancras, London, England, FHL microfilm 598,178, Genealogical Society of Utah, Salt Lake City; cited from “England Marriages, 1538–1973,” FamilySearch, online: https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:NKPP-8J7 (accessed 16 August 2018).

[41] Maya Jasanoff, Liberty’s Exiles: The Loss of America and the Remaking of the British Empire (Knopf: New York, 2011), 25–27; 115. Elizabeth and William both shared the experience of war and the loss of a mother. Grace Growden Galloway stayed behind in Philadelphia when her husband and daughter Elizabeth left for England. Grace was determined to maintain her real estate and personal property but her health declined and she died in 1782. For more on Grace Growden Galloway’s attempts to maintain her family’s estates and experience of the American Revolution see, Grace Growden Galloway and Raymond C. Werner, “Diary of Grace Growden Galloway,” Three Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 55, No.1 (1931): 32-64.

[42] Ibid.

[43] “Memorial of William Roberts,” 413.

[44] Elizabeth’s inheritance came from the vast Growden family fortune which she listed as £24,715 in her Loyalist claim dated October 1782. When her father Joseph Galloway’s assets were seized 1778 by the Continental Congress they included the vast estates brought into the marriage by Grace Growden Galloway. The confiscated property was sold by the legislature of Pennsylvania beginning in 1780. Grace fought to regain her fortune but died in 1781, leaving the confiscated estates to her daughter Elizabeth. It was finally decided that some of the properties, which had been owned by Elizabeth’s grandmother, Sarah, reverted to the heirs of Grace Growden Galloway. She continued to press her Trustees to recover her property from the State of Pennsylvania and was finally granted permission to purchase her property, which she did by 1787 with the exception of her property at Durham and Trevose. When Joseph Galloway died, his will was drawn up to protect his wife’s fortune from William, but his actual claim to his wife’s estates were contested by the Philadelphia courts. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that Galloway had no claim to his wife’s estates because of his treason, therefore, the property belonged to his wife’s heirs. For more on the Growden-Galloway-Roberts property see: Elizabeth Evans, Weathering the Storm: Women of the American Revolution (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1975), 185–244.

[45] At various times in his life William Roberts spent long periods of time living at Saling Green, the home of Loyalist Bartlett Goodrich, formerly of Nansemond area in Suffolk, Virginia – which is where he fled with his nine-month old daughter in May 1795 (Roberts, Travel Journal, 11-13; 32). Elizabeth Galloway Roberts and her father socialized with many American ex-pats of high social and political rank as Joseph Galloway pressed the British Government for assistance. They socialized with the families of Massachusetts Loyalists Elisha Hutchinson and Sir William Pepperell (both of whom appeared in her will) as well as the expatriate artist John Singleton Copley. Thomas Hutchinson and Peter Orlando Hutchinson, The Diary and Letters of His Excellency Thomas Hutchinson Esq. With an Account of his Administration when he was a member and speaker of the House of Representatives, and his Government of the Colony During the Difficult Period that Preceded the War of Independence, Compiled from the Original Documents Still Remaining in the Posession of his Descendants, Volume II (Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin, & Co., 1886), 308–309.

[46] In the play, Indians attack a young woman named Virginia and kill her family. Rescued by a handsome British soldier named Henry Valens, Virginia is taken to England as his ward. She falls in love with Henry, son of Lord Landmore, but believes him to be betrothed to another woman. Virginia cannot bear the thought of Henry marrying another and flees to the home of Mrs. Winlove. Through a series of incidents of mistaken identity and coincidence, the couple is reunited. William Roberts, The Fugitives: A Comedy (Warrington, England: Printed by W. Eyres, for John Stockdale Opposite Burlington House, Piccadilly London, 1791). There are two surviving manuscript books of his poetry in the Galloway Papers at the University of Wisconsin: Folder 69, “Two Poetry Books in the Hand of William Roberts,” Reel 1, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, University of Wisconsin Libraries, Madison, WI.

[47] Elizabeth Roberts, “Four Short Pieces of Dramatic Monologue,” in “Works by Elizabeth Galloway (Roberts),” Item 89, University of Wisconsin, Reel 2, Cairns Collection Part B, Galloway family, Cairns Collection of American literature by Women Authors who Flourished before 1901 (viewed on microfilm), Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, University of Wisconsin Libraries, Madison, WI.

[48] Joseph Galloway to Warner Mifflin and Ann Emlen, Emlen Family Papers, Collection Number 1396, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. The author extends appreciation and acknowledgment to Gary B. Nash for providing this information about the state of William’s and Elizabeth’s marriage and for bringing the repository of primary sources in the Emlen Family Papers to her attention.

[49] Elizabeth Roberts, “Poems by Elizabeth Roberts, 1793,” “Miscellaneous Poems,” and “Miscellaneous Pieces in Prose,” in “Works by Elizabeth Galloway (Roberts),” Item 86, University of Wisconsin, Reel 2, Cairns Collection Part B, Galloway family, Cairns Collection of American literature by Women Authors who Flourished before 1901 (viewed on microfilm), Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, University of Wisconsin Libraries, Madison, WI.

[50] Joseph Galloway to Warner Mifflin and Ann Emlen, Emlen Family Papers, Collection Number 1396, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. The author again extends appreciation and acknowledgment to Gary B. Nash for providing this information about the state of William’s and Elizabeth’s marriage and for bringing the repository of primary sources in the Emlen Family Papers to her attention.

[51] Roberts, Travel Journal, 11.

[52] According to Historic England’s list entry summary on Saling Grove, Bartlett Goodrich purchased both Saling Grove and Saling Park in 1795 from John Yeldham. Yeldham hired famed landscape designer Humphrey Repton to design the parks for Saling. In 1790, Repton recorded that he had created one of his Red Books of watercolor views of the estate. The book is no longer extant. Saling Grove List Entry Survey, Historic England, https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1000743 (accessed 28 August 2018).

[53] Bartlett Goodrich, a fellow Virginia loyalist, likely knew Roberts or his family in Portsmouth, Virginia. The Goodriches were early settlers of Nansemond County, Virginia who by the Revolution were successful merchants in Portsmouth. They became notorious for playing both sides when Bartlett’s father John Sr. made a deal with the Virginia Convention to transport 5000 pounds of gunpowder from the West Indies for use of the colonies and then pled their allegiance to Lord Dunmore. Bartlett and his brother John Jr. were accused of purchasing 300 pounds worth of British textiles in the West Indies and trying to pass the cargo off as Dutch Goods. Bartlett removed the labels in St. Eustacius and back in Virginia his brother altered the invoices and tried to pass the goods off as legal. The brothers were acquitted, but the family continued their privateering into the Revolution. Bartlett reached England by at least 1780 where he apparently was able to amass enough money for his father to state in his Loyalist claim that his son did not need restitution. For more on the Goodriches and their actions during the Revolution see George M. Curtis, “The Goodrich Family and the Revolution in Virginia, 1774–1776.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 84, no. 1 (1976): 49–74.

[54] English common law gave men the absolute right to control and maintain their children, typically siding in their favor in custody cases. By the end of the eighteenth century attitudes were changing in favor of placing young children, particularly girls under the age of seven, in the care of their mothers. Lawrence Stone, Broken Lives: Separation and Divorce in England, 1660–1857 (Oxford, England: Oxford University, 2011), 21.

[55] When Roberts and Elizabeth first married, they lived on Fitzroy Street in the newly built and fashionable West End area of Fitzrovia with Joseph Galloway. About the same time Francis Jukes lived just around the corner at 10 Howland Street. Jukes was a key figure of the English picturesque movement. He engraved aquatints for Saurey Gilpin (1733–1807) and William Sawrey Gilpin (c.1761–1843), brother and nephew, respectively, of William Gilpin (1724–1804), an originator of the picturesque theory. Jukes also etched a series of prints of American scenery after the work of the Scottish-born artist Alexander Robertson (1772–1841), including Mount Vernon and the Hudson River. See “Fitzroy Square,” in Survey of London: Volume 21, the Parish of St Pancras Part 3: Tottenham Court Road and Neighbourhood, ed. J R Howard Roberts and Walter H Godfrey (London, 1949), 52-63; British History Online: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol21/pt3/pp42-43 (accessed 16 August 2018); and “Francis Jukes” entry in Europeana Collections, online: https://www.europeana.eu/portal/en/explore/people/31399-francis-jukes.html (accessed 16 August 2018) and Historical Prints and Early Views of American Cities, Etc., (New York: New York Public Library, 1917), 8.

[56] Roberts, Travel Journal, 11–15.

[57] Evidence of this agreement is apparent in a letter written by Roberts to his attorney contesting terms, specifically visitation rights to his child. He references a version of the document that he agreed to in December, 1797 where he agreed to 24 visits a year to his daughter, which was reduced to 12 in the document he was presented with at time of writing. As leverage, he threatened to push up his journey to America in the Spring without signing the documents. See Folder 59, Letter from William Roberts to his attorney concerning rights to visit his child, Grace Roberts, 17 January 1798, Galloway Papers, Reel 1, Folder 59, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, University of Wisconsin Libraries, Madison, WI.

[58] Private separation agreements were common and such records can sometimes be found in archived family collections. Stone, Broken Lives, 360. References to their agreement are found in a letter that William Roberts wrote to his lawyer complaining about the lawyer’s mishandling of the separation agreement’s terms: Letter from William Roberts to his attorney concerning rights to visit his child, Grace Roberts, 17 January 1798, Galloway Papers, Reel 1, Folder 59, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, University of Wisconsin Libraries, Madison, WI.

[59] Although an apocryphal source, a nineteenth-century history of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, recorded Elizabeth and her husband had a separation agreement and that “she gave her husband £2000, for the privilege of retaining their only child Grace Ann, who was only allowed to see her father in the presence of a third person.” See W.W.H Davis, The History of Bucks County, Pennsylvania: From the Discovery of the Delaware to the Present Time (Doyldestown, PA: Democrat Book and Job Office Print, 1876), 148.

[60] The Growden-Galloway estate was the subject of legal turmoil for several decades. Since Elizabeth’s fortune was essentially her mother’s, Joseph had no right to it technically. The threat that William would come into possession of his wife’s inheritance – which itself was of a tenuous nature – was dependent on international rights of coverture. In England, William would have been entitled to his wife’s fortune, but in America where laws of coverture were abolished, it would be in her possession. In 1806, Elizabeth was granted possession of her estates in America. Will of Joseph Galloway, proved 28 September 1803, Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions, Will Registers, Class: PROB 11, Piece: 1398, p. 368, The National Archives, Kew, England, cited from England & Wales, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384-1858, Will Register 1802–1804, available online by subscription: https://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=5111 (accessed 28 August 2018).

[61] Will of Elizabeth Roberts, proved 10 July 1815, Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions, Will Registers, Class: PROB 11, Piece: 1571, p. 37, The National Archives, Kew, England, cited from England & Wales, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384-1858, Will Register 1815–1818, available online by subscription: https://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=5111 (accessed 28 August 2018).

[62] Roberts, Travel Journal, 9. Four Lane End is now known as the town of Langhorne, Pennsylvania. Elizabeth and Grace Ann did not remain in the United States, but returned to England.

[63] Ibid. For John Ireland, see Matthew Livingston Davis, Report of the Case Between the Rev. Cave Jones, and the Rector and Inhabitants of the City of New-York in Communion of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the State of New-York (New York: printed by William A. Davis, 1813), 44, 124, and 260–261; available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=WyUWAAAAYAAJ&dq=John+Ireland+St+Ann%27s+church+brooklyn&q=john+ireland#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed 28 August 2018).

[64] Roberts, Travel Journal, 15.

[65] Ibid, 18.

[66] Ann “Nancy” Roberts married a merchant from Manchester named John Taylor, who had connections to the Norfolk area. According to William’s travel journal, they resided in Chester and Manchester from 1787 to 1791, when the couple embarked for Norfolk where Ann remained for the rest of her life. John Taylor died in England in 1829 and left his wife all of his American properties. It appears that he returned to England to help his sister settle her deceased husband’s estate and that he died in England. See Will of John Taylor, England & Wales, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384–1858, PROB 11: Will Registers, 1829–1831, Piece 1761: Liverpool, Quire Numbers 550–600 (1829), pp. 52–53, available online by subscription: https://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=5111 (accessed 16 August 2018).

[67] Roberts, Travel Journal, 20.

[68] Gary Nash makes the connection between William Roberts and the character Guillaume Roberts who filled St. John de Crèvecoeur in about Warner Mifflin in the French edition of The American Farmer. Mifflin and Roberts were cousins, see Nash, Appendix 1 247-251; “To Jefferson from Roberts, 24 July 1803,” The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 41, edited by Barbara B. Oberg (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 2015), 111–112; also available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-41-02-0077 (accessed 14 August 2018).

[69] Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (London: printed for John Stockdale, 1787), 36; available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=-KlbAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed 28 August 2018).

[70] Henrietta Liston, “North America 1800 – Journey to the Natural Bridge in Virginia,” MSS.5696-5704, National Gallery of Scotland, p. 15.

[71] See William Gilpin, Observations on the River Wye (1770); Uvedale Price, An Essay on the Picturesque as Compared with the Sublime and Beautiful (1794); and Richard Payne Knight, An Analytical Inquiry into the Principles of Taste (1805).

[72] William Gilpin, An Essay upon Prints, containing Remarks upon the principles of picturesque Beauty… (London: Printed by G. Scott for J. Robson, 1768), x; available online: https://archive.org/details/essayuponprintsc00gilp (accessed 28 August 2018).

[73] Adrian Tinniswood, The Polite Tourist: Four Centuries of Country House Visiting (London: National Trust, 1998), 113.

[74] For examples, see Powell, Nature and Culture; Linda S. Ferber and the New-York Historical Society, The Hudson River School: Nature and the American Vision (New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2009); and Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, Amy Ellis, and Maureen Miesmer, Hudson River School: Masterworks from the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art (New Haven, CT: Yale University, 2003).

[75] American artists and writers dismissed the English definition of the sublime from the eighteenth century and instead strove to focus on moral and contemplative aspects of nature. At a time when many American artists and writers boasted of their “awesome wilderness,” but were drawn to more tranquil scenes of nature, they altered the popular concept of the sublime to “fit their more benign perceptions of nature” (Robert Doak, “The Natural Sublime and American Nationalism: 1800–1850,” Studies in Popular Culture, Vol. 25, No. 2 [October 2002]: 18). For more on this topic see: Views and Visions: American Landscapes before 1830 (Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery, 1986) and Barbara Novak, Nature and Culture: American Landscape and Painting, 1825–1875 (Oxford, UK and New York: Oxford University, 2007), 33–34.

[76] Bruce Robertson, “The Picturesque Traveler in America,” in Views and Visions: American Landscapes before 1830 (Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery, 1986), 190–199.

[77] Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, 28; available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=-KlbAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed 28 August 2018).

[78] “From Thomas Jefferson to Maria Cosway, 24 December 1786,” The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 10, edited by Julian P. Boyd (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 1954), 627–628; also available online: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-10-02-0481 (accessed 28 August 2018).

[79] “From Thomas Jefferson to Angelica Schuyler Church, 17 February 1788,” The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 12, edited by Julian P. Boyd (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 1955), 600–601; also available online: http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-12-02-0638 (accessed 28 August 2018).

[80] See Margaret Pritchard, “The Protracted View: A Relationship between Mapmakers and Naturalists in Recording the Land,” in Knowing Nature: Art and Science in Philadelphia, 1740–1840, edited by Amy R. W. Meyers (New Haven, CT: Yale University, 2012), 28–30.

[81] Anna O. Marley, “Landscapes of the New Republic at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello,” in Building the British Atlantic World: Spaces, Places, and Material Culture, edited by Daniel Maudlin and Bernard L. Herman (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2016), 87–88.

[82] “From Jefferson to John Trumbull, 20 February 1791,” The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 19, edited by Julian P. Boyd (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 1974), 298–301; also available online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-19-02-0067 (accessed 28 August 2018).

[83] The two views were bound as folding prints and were also included in the first English-language edition published a year later. François-Jean Chastellux, Voyages dans l’Amérique Septentrionale, dans les années 1780, 1781 [et] 1782, Tome Second (Paris: Chez Prault, 1786) and François-Jean Chastellux, Travels in North-America, in the years 1780, 1781, and 1782, Vol. 2 (London: G.G.J. and J. Robinson, 1787). One of these engravings, Perspective Taken from Point B, was also reproduced in the September 1787 issue of Columbian Magazine; available online: https://archive.org/details/columbianmagazin17861787phil (accessed 28 August 2018).

[84] Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, third American edition (New York: Printed by M. L. and W. A. Davis for Furman & Loudon, 1801).

[85] A watercolor painting of the Natural Bridge attributed to Weld is in the collection of the Virginia Historical Society (Acc. 2002.648). See Isaac Weld, Travels Through the States of North America, and the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada: During the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797 (London: Printed for John Stockdale, Piccadilly, 1800).

[86] In 1828 or 1829, Jacques-Gerard Milbert (1766–1840) published a view of the Natural Bridge in his atlas, Itinéraire Pittoresque du Fleuve Hudson et des Parties Laterales. The image was engraved after “V. Roberts” and the bridge noted to be owned by Thomas Jefferson. Interestingly, the foreground figures in this print are Native Americans and the background figures have been replaced by a pair of deer. In the absence of the original sketches and oil painting once housed at Monticello, it is impossible to know for sure if either Roberts fancifully added Native Americans and deer to his painting or if Milbert made the changes in his engraving. For an image of this print, see http://www.swaen.com/antique-map-of.php?id=13360 (accessed 28 August 2018).

[87] Views and Visions: American Landscapes before 1830, 22

[88] For pointing out the reversed flow of the Potomac, the author thanks Matt Webster, Director, Grainger Department of Architectural Preservation and Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

[89] Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, 27–28; available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=-KlbAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed 28 August 2018).

[90] Gilpin, Observations on the River Wye, 61.

[91] Batson referred this second watercolor as a “wash sketch” and suggested that Roberts used a camera obscura to delineate his design from the first watercolor study. Also, in preparation for printmaking he reduced the size of this second watercolor to the size of a travel book, perhaps further evidence of his intent to publish a travelogue of his travels. Batson, “Virginia Landscapes,” 44–45.

[92] Batson describes Roberts’s artistic choices with his Harper’s Ferry view in detail. Ibid, 44-46.

[93] In the summer of 1804, Roberts travelled through Washington, DC, through Maryland, and made a tour of Pennsylvania returning in December to Norfolk. “Item 68 Mileage record book 1804-05 in the hand of William Roberts,” Reel 1, Cairns Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, University of Wisconsin Libraries, Madison, WI.

[94] “To Thomas Jefferson from William Roberts, 18 July 1804,” online: Founders Online, National Archives, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-0099 (this is an Early Access document from The Papers of Thomas Jefferson; accessed 28 August 2018).

[95] In 1806 when he returned to England, he spent time between a home in Laleham and London. He attempted several times to visit his daughter and corresponded infrequently with his wife over legal matters. Reel 1, Cairns Collection, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, University of Wisconsin Libraries, Madison, WI.

[96] “Monthly Retrospect of the Fine Arts,” The Monthly Magazine, Vol. 25 (April 1808): 250.

[97] “The Natural Bridge,” The Observer (London), 29 May 1808, p. 1.

[98] Batson, “Virginia Landscapes,” 36; “Junction of the Potomac and Shenandoah, Virginia,” Image ID 54313, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library; available online: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-7b55-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (accessed 16 August 2018).