The best description of the free African American ornamental and plain plasterer and bricklayer Harry Mordecai is found in his January 1853 obituary published in The Frankfort Commonwealth (Figure 1).[1] Titled “Honor To the Lowly and Upright,” the obituary describes a pious man and a successful artisan who used his skills to purchase freedom for himself and his family:

Harry Mordecai, from youth to old age a much respected colored inhabitant of Frankfort, departed this life on Monday, Jan. 3d, 1853, aged about 70 years. He was born a slave, and instructed by his master in the business of bricklaying, plaster, &c. By his energy, industry and economy, he bought his own freedom, and that of his wife and several children, afterwards reared and supported a very large family, and left at his death a very considerable estate for one in his humble position. He lived long, usefully, benevolently and piously; enjoyed the confidence and respect of all who knew him, and died in the triumph of a Christian’s faith.[2]

Mordecai’s obituary does not reveal the specific contributions he made to Frankfort’s built landscape. Nor does it detail how a man born into slavery engaged and circumnavigated the city’s white society to bring freedom to and support “a very large family” and leave “a very considerable estate.” This brief research note endeavors to provide those details about Harry Mordecai, one of Kentucky’s most important African American craftsmen of the nineteenth century.

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

Three years before his death, Harry Mordecai was recorded in the 1850 United States Census as a free mulatto living in Frankfort, Franklin County, Kentucky (Figure 2). The census also reveals that he was born about 1784 in Virginia. Although his parentage is unknown, Mordecai arrived in Kentucky sometime by 1796 with the man who enslaved him, Francis Radcliffe. The first record of Radcliffe in Frankfort appears in the 1796 tax list for Franklin County.[3]

A Revolutionary War veteran, Francis Radcliffe was born in 1755 in Chesterfield County, Virginia.[4] In 1813 Radcliffe enslaved a total of ten African Americans, four of whom were males above the age of sixteen.[5] One of those four men was Harry Mordecai, who would have been about thirty years old at the time. Radcliffe died in Frankfort a year later, in 1814, when he was about sixty years old.[6] Upon settlement of his estate in 1816, Harry Mordecai became the property of Radcliffe’s son, George Radcliffe.

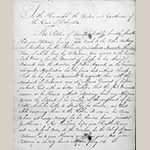

Mordecai is recorded on the 1816 Franklin County tax list as “Mordecai, Henry (freeman),” suggesting he was working and living independent of George Radcliffe’s household.[7] The same tax list records George Radcliffe enslaving one “black over the age of 16,” which documents Harry Mordecai a second time in 1816.[8] A year later, Radcliffe’s 1817 county tax record lists no African Americans in his household.[9] This is significant because on 20 March 1817 Radcliffe had freed Harry Mordecai (Figure 3). The formal notice of emancipation reads:

Know all men, by these presents that I George Radcliffe of the County of Franklin and State of Kentucky Have and by these presents doth liberate, set free, and Emancipate my mulatto man slave Harry Mordica hereby discharging him from all further servitude to me or my heirs and declaring and conferring to him his freedom in as full and simple a manner as if he had been born free. And further I do hereby covenant, promise and agree for myself, my Heirs, Executors, or administrators, in consideration of the faithful services rendered by the said Harry Mordica to my Father as well as to myself and other valuable considerations me hereunto receiving, that I will support and maintain the said Harry Mordica in his freedom and emancipation against the claim of all and every creditor or legal representative of my Father Francis Radcliffe, or any creditor or representative of myself and against the claim and demand of any & every other person or persons whatsoever. In testimony whereof I have hereunto set my hand and affixed my seal this Eleventh day of March in the year One thousand eight hundred and seventeen signed, sealed, acknowledged and delivered in the presence of

Henry F. Hume

Jno. Newberry

James Moss

Franklin County Court[10]

The fact that George Radcliffe emancipated Mordecai nearly immediately after his father’s estate was settled suggests that George and Harry had a close relationship. Neither Francis Radcliffe nor his estate freed Mordecai. But George Radcliffe did free Mordecai as soon as he had the authority to do so. Considering that the two men were about the same age, most likely grew up together, and that Mordecai was described in more than one document as mulatto, it is possible that George Radcliffe and Harry Mordecai were half-brothers.

Mordecai’s freedom was not granted without compensation. Any agreement between the Radcliffes for Mordecai to earn his freedom almost certainly provided a monetary benefit to the Radcliffe family. If Mordecai bought his freedom, he most likely participated in the system of “hiring out” to acquire the sum required.

While Kentucky’s 1798 slave code prohibited the hiring out of enslaved workers, many slaveholders ignored the statute. Different methods of “slave hiring” were described in A History of Blacks in Kentucky: From Slavery to Segregation, 1760–1891 by Marion B. Lucas:

Many small farmers rented slaves from neighbors on an informal basis. They were usually looking for slaves with particular skills to accomplish specific tasks. Hired slaves worked for a day, week, or perhaps a month… . Kentucky slaveholders [also] leased their slaves to regional farmers on a more formal basis. They drew up written agreements stipulating all conditions, usually in the form of promissory notes. If neighbors failed to hire available bondsmen, owners might auction their services to the highest bidder… . On the first day of each year almost every sizeable town, from the mountains to the Mississippi River, held slave hiring auctions on the public square.[11]

A third method that Lucas cited was enlisting agents on a commission basis. Some enslaved individuals made arrangements with owners that permitted them to find and negotiate their own work and pay owners a fixed sum.

From the leasing process to hiring out their own services, this system was the best path for enslaved people to purchase their freedom. It is likely the process that Harry Mordecai employed to attain his freedom. Such a conclusion is supported by an 1815 payment to Mordecai—two years before his manumission—of $61.42 by the Commonwealth of Kentucky for plastering an office.[12]

Once free, African Americans still faced significant challenges. In antebellum Frankfort, Kentucky, freedom for a free person of color was quite different than for a white person. Historian Lewis J. Bellardo Jr. wrote in 1975 about a special census of Frankfort’s free blacks called in July 1842. This “census” was actually a forced assembly of the city’s free African Americans to assess their threat to the white population:

In 1842 the city fathers of the town of Frankfort, Kentucky, were sufficiently disturbed by the racial situation in the town to summon all free blacks to appear 16 July before the city Board of Trustees. At that meeting the free black inhabitants of Frankfort—they could hardly be called citizens—were examined, and Frankfort whites spoke either on their behalf or to their detriment. Notations on each family were entered into a small soft-covered book. A number of blacks were expelled from the city, one was arrested, and others were warned to change their behavior or receive like punishment… . The strangest thing about the examination is that in some cases persons with favorable recommendations from white citizens were punished anyway.[13]

Although only portions of this “small soft-covered” book survived into the last quarter of the twentieth century, Bellardo transcribed what was available. That transcription includes an entry for Harry Mordecai, and reveals a household that included his wife, five of their children, a grandchild, and an unrelated enslaved person:

Mordecai, Harry, 57, plasterer, etc., $3,000, character well known to be good. Rachel Mordecai, 45, wife. James Mordecai, 19, child. Charles Mordecai, 16, child. Sevelia Mordecai, 12, child. Eugenia Mordecai, 11, child. Julia Mordecai, 11, gr. d., Kitty Mordecai, 9, child. Invenor Jones, 16, bound.[14]

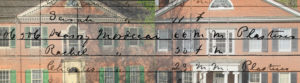

Eight years later, the 1850 United States Census recorded the Mordecai household as Harry and Rachel with four of their children: Charles, Sevelia, Eugenia, and Kitty, as well as a thirteen-year-old boy born in Mississippi named Ealam Miller (see Fig. 2).[15] These individuals made up the free people in the Mordecai household. The 1850 United States Census (Slave Schedule) recorded five enslaved people in the Mordecai household (Figure 4). All five individuals were men, ranging in age from twenty-two to forty-five. Their names or relation to Harry Mordecai are not given.

Mordecai’s relationship to those reported as his property in the 1850 slave schedule, as well as his relationships to Francis and George Radcliffe, reflect the tragic lacunae and unspoken kinships created by the institution of slavery. Blatant omission and intentional ambiguity combine to create significant difficulties for those intent on understanding and interpreting these historical documents today.

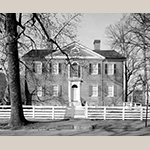

Liberty Hall

On 3 November 1796, Francis Radcliffe and George Rowland contracted with Senator John Brown to complete the brickwork for Brown’s Frankfort residence known as Liberty Hall (Figure 5).[16] Enslaved by Francis Radcliffe at the time, twelve-year-old Harry Mordecai would have assisted and probably trained on the job. Mordecai is also documented as having worked on the interior plaster walls of Liberty Hall, although to what extent is unclear.[17] What is certain is that when construction at Liberty Hall was finished sometime in 1803 or 1804, Mordecai would have, as his obituary claimed, been fully “instructed by his master in the business of bricklaying, plaster, &c.”[18]

Like Mordecai, the owner of Liberty Hall, John Brown, was from Virginia. He studied law at the College of William and Mary and read law under Thomas Jefferson. He represented Virginia in the Confederation Congress (1787–1788) and was a U.S. Congressman from Virginia (1788–1792) when he introduced the bill for Kentucky statehood. Upon statehood, Brown represented Kentucky as one of its first two United States senators (1792–1805).[19]

Now recognized as a national historic landmark, Liberty Hall has been described as one of the finest examples of Federal architecture in Kentucky by architectural historian Clay Lancaster:

It features a pedimented three-bayed central pavilion, whose focus is a beautiful colonnetted doorway with a fine Palladian window superimposed, and having a lunette set in the tympanum of the pediment on axis. The exquisite cornice carries left to right across the entire façade.[20]

The brickwork of Liberty Hall is laid in Flemish bond with five bays, the central three of which are three-and-three-quarter inches proud from the outer two. The belt course is four bricks deep and the molded brick water table is pronounced (Figure 6). The chimneys are substantial with decoratively corbelled tops consisting of the tops having four or five rows of bricks that step out from the base, topped with another four or five rows of bricks that step in toward the top of the cap (Figure 7).[21]

Mordecai’s involvement in finishing the interior plaster walls of Liberty Hall is suggested through a much later correspondence of John Brown’s wife. On 3 May 1835, Margaretta Mason Brown wrote to tell her daughter-in-law that she had temporarily moved into her bedroom (Figure 8):

We have all (including Mary and Harriet) taken possession of your room, as mine is dismantled, and awaiting the pleasure of Harry Mordecai to commence whitewashing—I hoped to avail myself of the absence of all the males of the family to have the house put in order, but I fear Harry’s dilitoriness will defeat my object.[22]

It is unknown whether Mrs. Brown’s choice of Mordecai to perform this work thirty years after Liberty Hall was completed meant that he had performed the plasterwork in the original construction of the house or if he was simply the current contractor. What is clear from Margaretta’s letter is that Mordecai’s work was in demand by 1835, causing her frustration in awaiting his services.

Kentucky’s Old State Capitol

John Haviland, in his book The Builders’ Assistant, published in Philadelphia in 1818, detailed the extent of services that early nineteenth-century plasterers might perform and their methods.[23] Haviland also provided a universal pricing schedule for plaster work.[24] Several plaster motifs in the Old Kentucky State Capitol were apparently adapted from Haviland’s book (Figure 9), thus a copy was likely available locally during Mordecai’s era and possibly governed his work.

The basic purpose of a plasterer is to make level and smooth interior walls and ceilings that can then be painted or papered. On outside walls of brick or stone, the plaster could be applied directly as the rough surface yielded a strong bond. On wood framed walls and ceilings, the plasterer would first attach wood laths with nails. Laths were small boards about one-half by one inch, in three- to four-foot lengths. The laths were installed horizontally in parallel runs covering the entire wall or ceiling, with each run separated by a gap of about one inch. When wet plaster was applied with a trowel, it squeezed through the gaps and swelled, becoming fixed to the lathwork when hardened.

Two types of plaster were applied in several applications. The first was called “lime and hair, or coarse stuff,” which was common mortar (lime, sand, and water) with animal hair from a tanyard mixed in with a rake. The hair reduced cracking by increasing the tensile strength of the plaster. Next came the finish application(s), called “fine stuff,” which was pure lime and water. Haviland discusses recipes, mixing methods, and resultant plaster qualities in a section of his book titled “Mortars.”[25] The source of the lime used by local artisans has not been identified, but it could have come from bone, mussel shells, or limestone, which underlies the region and was quarried locally by the Kentucky State Penitentiary.

Beyond basic interior walls, a plasterer might also be called upon to create cornice moldings, coffered ceilings, or decorative ornaments like those found in the Old Kentucky State Capitol (Figures 10 and 11). Small moldings of plaster could be made using a wooden trowel with one edge cutout in the profile of the molding. Larger moldings, such as cornices or coffered ceilings were framed, laths installed, and plastered like small walls. Ornaments were made by creating a mold for casting plaster. Once hardened, the ornaments were attached with wet plaster. Such moldings and/or ornaments could be relatively simple or quite complex.

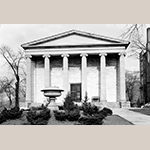

The Old Kentucky State Capitol is a Greek Revival style building with the front emulating the Temple of Minerva Polias at Priene (Figures 12 and 13). It was designed by Gideon Shryock, a Lexington, Kentucky architect. Shrycock was twenty-five years of age at the time of his design and the Kentucky State Capitol was his first building. Other structures credited to Shryock include Old Morrison Hall at Transylvania University in Lexington, the Orlando Brown House in Frankfort, and the Jefferson County Courthouse in Louisville, Kentucky, as well as the Old State House at Little Rock, Arkansas.

Construction of the Old Kentucky State Capitol began in 1827 and was completed in 1830. It was the home of the Kentucky General Assembly until 1910. Recognized as a National Historic Landmark, the building is open for public tours operated by the Kentucky Historical Society.

Of the buildings discussed in this article, Kentucky’s Old State Capitol has by far the most elaborate plasterwork. The Kentucky Historical Society credits the plasterwork throughout the Old State Capitol to Harry Mordecai.[26] This assignment is based upon an oral tradition that Mordecai’s descendants still had the molds that their ancestor used in performing that work, until they were destroyed in the 1937 flood in Frankfort. The earliest publication of that tradition is found in a July 1945 article in The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society authored by the journal’s editor, Bayless E. Hardin.[27] There are some payments made by the Commonwealth to Mordecai, before, during, and after the period of construction of the Old State Capitol listed in the Journals and Acts of the General Assembly. Those payments from 1815 to 1832 are detailed in Figure 14. The payments made to Mordecai during the construction of the Old State Capitol total only $29.50, an amount that does not equal the building’s extensive and elaborate plasterwork.

In the Journal of the House of Representatives of 1828, the commissioners noted that “Mr. Shryock believes that to complete the portico, dome and interior workmanship, the sum of $20,000 will be sufficient.”[28] The majority of the plaster work appears to have occurred in 1830, because at the end of that year the commissioners commented that the expenses exceed the estimates for several reasons, one of which was “the ornamental plastering was much more expensive than had been estimated.”[29] Most significantly, the legislature approved an act in 1831 instructing the auditor of public accounts to pay the ornamental plasterer William S. Shackleford the sum of $232.03 “for the balance due said Shackleford for all the materials, plain and ornamental plastering, and every other claim arising out of his contract for plastering the capitol… .”[30] The legislators also authorized payment to Shackleford, “as per account, one hundred and fifty dollars.”[31]

It is apparent from historical documents that the ornamental plasterwork in the Old State Capitol was completed by many hands. Therefore, the entirety of the plasterwork was not likely to be done by any one person or even any one small crew. To that end, the oral tradition that Mordecai, possibly with his sons, were the sole plasterers of the Old State Capitol, or oversaw the project is not accurate. William Shackleford held the primary contract and most definitely hired many plasterers to assist him, which could have included Mordecai.

The documentary evidence, however, does establish that Mordecai did plasterwork in the offices that housed the senate and in at least one other office for the state before the construction of the Old State Capitol commenced. It is possible that Mordecai chose not to bid on the project having learned from Francis Radcliffe the difficulty of receiving payment from governmental entities. In 1786 Radcliffe had to make appeal to the Virginia House of Delegates for payment for his work on public buildings (Figure 15).[32] It is also possible that Mordecai was working elsewhere during the time most of the plasterwork was installed at the Old State Capitol, as he is not on the Franklin County tax lists during much of that time.

The Orlando Brown House

Senator John Brown of Liberty Hall bequeathed his house to his first-born son, Mason. He then divided his land and between 1835 and 1836 built a second house adjoining Liberty Hall. This house was for Orlando, Brown’s second son. Orlando Brown graduated from Princeton University and Transylvania University’s law school. He first practiced law in Alabama, and then moved his practice to Frankfort. He was the owner and editor of the Frankfort Commonwealth newspaper from 1833 to 1842, then returned as editor of the newspaper in 1862. He served as Kentucky’s Secretary of State under Governor John J. Crittenden and as the United States Commissioner of Indian Affairs during Zachary Taylor’s presidency.[33]

The Orlando Brown House (Figure 16) was built in the Greek Revival style and designed by Gideon Shryock, the same architect as Kentucky’s Old State Capitol. A circa 1835 accounting of the building costs for the Orlando Brown House reveals that Harry Mordecai was paid $567.75 for plastering.[34] Another plasterer, Joseph Gayle, was paid $380.75, and a painter and glazer recorded as “Is. Marshall” received $175.[35] This document likely does not include the entirety of the costs for building Orlando Brown’s house, as some items on the list state they are second accountings of payments. In a 23 June 1836 letter to his father, Brown reports on Mordecai’s progress:

All the rooms on the side next Mrs. Love, including the ell are now ready for plastering and the kitchen and room above it are lathed. The passage floor below is laid and also the floors in the upper room above the drawing rooms are laid—the windows and the wash boards nearly laid down. Everything is now going on with dispatch. Harry has his mortar prepared and will commence operations in a day or two.[36]

The plasterwork at the Orlando Brown House did not include cornices or ornamentation like that created for Kentucky’s Old State Capitol; rather, the house’s plasterwork consisted of creating level and smooth walls and ceilings suited for painting or papering. That the plaster on the house’s walls has remained level and smooth nearly two hundred years later is a tribute to Mordecai’s craftsmanship.

Harry Mordecai undoubtedly was responsible for the brick and plasterwork of many more central Kentucky houses and buildings than those discussed above. Unfortunately, the account books, ledgers, and receipts recording such work rarely survives. For now, Mordecai’s documented contributions to Kentucky’s built environment is limited to Liberty Hall and the Orlando Brown House.

Benevolence and Piety

Mordecai’s obituary places great emphasis on his “energy, industry and economy” and that he “lived long, usefully, benevolently and piously.” The historical documents support those claims. The Franklin County tax lists and census records over the years document the presence of any number of African Americans in Harry Mordecai’s household. These reflect Mordedai’s growing family, certainly, but also substantiate his purchase and emancipation of family members and most likely many others. Mordecai’s tax record for Franklin County in 1816, for instance, includes three “black males over 16 years of age.”[37] It could be important that the 1813 tax record for the man who enslaved Mordecai, Francis Radcliffe, lists “four black males over 16.” Since one the four would have been Mordecai, it could be that the three men recorded in Mordecai’s 1816 household were related to him in some way.[38]

By 1823, only six years after earning his freedom, the Franklin County tax records reveal that Harry Mordecai had purchased a house and lot in South Frankfort and owned four horses.[39] This 1823 listing also shows that Mordecai was taxed for an enslaved African American over the age of sixteen. Five years later the county again taxed Mordecai for an enslaved individual over the age of sixteen.[40] Continuing this trend, in 1830 Mordecai had four enslaved people in his household.[41]

In 1833, Mordecai obtained freedom for his wife Patsey and their five children: James, Charles Henry, Servilia, Eugenia, and Catherine “Kitty”.[42] To purchase his family’s emancipation, Mordecai may have sold all of his taxable assets since he does not appear on the Franklin County tax lists again for two years. Patsey died less than ten years later. Mordecai had married a woman named Rachel when his family was recorded among Frankfort’s free blacks in 1842.[43]

Matters of faith were as important to Mordecai, if not more so, than business success. He and his family were members of the Saint John African Methodist Episcopal Church in Frankfort (Figure 17). The city’s first African Methodist Episcopal congregation was formed in 1839 with a church building constructed that same year at the corner of Clinton and Lewis streets.[44] The land for the church had been given to Benjamin Dunmore and Benjamin Hunley by Rebecca Anderson Tripplet, a white woman that employed Dunmore and Hunley.[45]

In the 1840s, the land and church were deeded in trust to Harry Mordecai and George Harlan.[46] According to Dr. Robert Strode’s doctoral dissertation on the history of Saint John A.M.E., Mordecai and Harlan served as the church’s first ministers:

As to the ministers prior to 1865 who served St. John, it is not clear whether they were free men or servants of the white slave owners, because Harry Mordecai and George Harlan were ministers given property where St. John is currently located.[47]

Mordecai served a leadership role at St. John A.M.E. until about 1850, when Rev. Henry Henderson became the pastor.[48]

As previously discussed, the 1850 United States Census (Slave Schedule) recorded five enslaved people in the Mordecai household (see Fig. 4). Despite the significant costs of continually purchasing freedom for others, Harry Mordecai’s brick and plasterwork businesses provided enough for him to have purchased three town lots in 1852, as well as nine horses and a cow, totaling $2,525 of taxable value.[49] His will, written on 2 January 1853, the day before he died, dispensed an estate that provided for his wife Rachel’s needs during her lifetime and vested title of all his property for the benefit of his children.[50]

— ♦♦◊♦♦ —

The narrative of Harry Mordecai’s life, briefly summarized in his obituary and presented in greater detail in this research note, is one of industry, craftsmanship, and compassion. As a craftsman, his legacy can be seen on Frankfort’s material landscape, most notably at Liberty Hall and the Orlando Brown House. As a man, Mordecai contributed greatly to his family and community through securing freedom for many enslaved people and his leadership of St. John A.M.E. Church.

Awareness of Harry Mordecai and his achievements is growing, largely due to the countless years of research by his third great granddaughter, Jacqueline Ridley (Figure 18). In an article for the Kentucky Historical Society, titled “Harry Mordecai: Ancestor and Artisan,” she inspirationally tells the story of her search and discoveries.[51] Jacqueline concluded her article with the hope that the growing awareness of Harry Mordecai and his accomplishments will reveal more of Kentucky’s free and enslaved African American craftspeople:

I wonder how many other enslaved and freed artisans performed work at the Old State Capitol. These artisans are the ones who contributed to the building of grand monuments that still stand today as testament to Frankfort’s history. It is my desire that other people will use Harry’s story as a catalyst to begin research of their ancestors and, hopefully, unearth their untold stories.[52]

Sharon Cox is an independent scholar in Richmond, Kentucky. She extends gratitude to those without whom this article would not have been possible: Mordecai descendants Jacqueline Ridley and Judith Lang; Preservation Virginia Curator Lea Lane; the staffs of the Kentucky Historical Society and Liberty Hall Historic Site; and her husband, Mack Cox. She can be reached at [email protected].

[1] The exact edition of the Frankfort Commonwealth in which Mordecai’s obituary was published is unknown, but it was reprinted in the 28 January 1853 edition of Cincinnati’s The Ohio Organ of the Temperance Reform (p. 6).

[2] The Ohio Organ of the Temperance Reform (Cincinnati, OH), 28 January 1853, 6.

[3] Alternative spellings of Radcliffe’s name in the records are “Ratliff,” “Ratcliff,” “Ratcliffe,” or “Radcliff.” Francis Radcliffe, Franklin County Tax List, 1796, p. 5, MSS 67, Franklin County Tax Lists, 1797–1818, Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, KY; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS3J-K3W4?i=39&cat=155188 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[4] Lineage Book, National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Vol. 67 (1908) (Washington, DC: National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, 1923), 299; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/library/books/records/item/760928-lineage-book-67-66001-67000?offset=1 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[5] Francis Radcliffe, Franklin County Tax List, 1813, p. 40, MSS 67, Franklin County Tax Lists, 1797–1818, Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, KY; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS3J-K3S9?cat=155188 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[6] Franklin County, Kentucky, Will & Settlement Book B, p. 136, May 1814, Franklin County Courts Clerk’s Office, Frankfort, KY.

[7] Henry (Harry) Mordecai, Franklin County Tax List, 1816, p. 34, MSS 67, Franklin County Tax Lists, 1797–1818, Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, KY; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS3J-K97K-5?i=39&cat=155188 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[8] George Radcliffe, Franklin County Tax List, 1816, p. 44, MSS 67, Franklin County Tax Lists, 1797–1818, Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, KY; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS3J-K97Y-Z?i=49&cat=155188 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[9] Harry Mordecai has not been found in the 1817 tax list for Franklin County. George Radcliffe, Franklin County Tax List, 1817, p. 8, MSS 67, Franklin County Tax Lists, 1797–1818, Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, KY; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS3J-K9WM-P?i=75&cat=155188 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[10] Franklin County, Kentucky, Deed Book F, 1817, p. 126, Franklin County Court Clerk’s Office, Frankfort, KY.

[11] Marion B. Lucas, A History of Blacks in Kentucky: From Slavery to Segregation, 1760–1891 (Frankfort: Kentucky Historical Society, 2003), 101–102.

[12] “Mordecai, Harry,” Notable Kentucky African Americans Database, online: http://nkaa.uky.edu/nkaa/items/show/3164 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[13] Lewis J. Bellardo Jr., “Frankfort, Kentucky, Census of Free Blacks, 1842,” National Genealogical Society Quarterly, Dec. 1975: 272.

[14] Ibid, 274.

[15] Mordecai’s eldest son, James, was nineteen years old when recorded by the city in 1842. He would have been twenty-seven years old in 1850 and presumably living on his own by that time, although a search of the 1850 United States Federal Census did not reveal his location.

[16] Charles E. Peterson and Cynthia S. Cargas, “The Past and Future of Liberty Hall, Frankfort, Kentucky,” pp. 21–26, preliminary report submitted to Liberty Hall Inc. and the National Society of Colonial Dames, 1978, Liberty Hall Historic Site Archives, Frankfort, KY.

[17] Letter from Margaretta Brown to Mary Watts Brown, 3 May 1835, Orlando Brown Papers, Filson Historical Society, Louisville, KY.

[18] Pat Watlington, “The Building of ‘Liberty Hall’,” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Vol. 69, No. 4 ((1971): 313–318. Franklin County, Kentucky, Deed Book F, 1817, p. 126, Franklin County Court Clerk’s Office, Frankfort, KY.

[19] “Liberty Hall Family,” Liberty Hall Historic Site website, online: https://www.libertyhall.org/learn/the-brown-family/liberty-hall-family (accessed 29 June 2020).

[20] Excerpted from Clay Lancaster, Critique on Liberty Hall, 1980; cited from “Architecture,” Liberty Hall Historic Site website, online: https://www.libertyhall.org/learn/architecture-article (accessed 29 June 2020).

[21] Liberty Hall, National Register of Historic Places, ID 71000344, National Park Service, Washington, DC; available online https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/AssetDetail?assetID=2bc72d7b-0d6b-4943-a404-d93692b4a117 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[22] Letter from Margaretta Brown to Mary Watts Brown, 3 May 1835, Orlando Brown Papers, Filson Historical Society, Louisville, KY.

[23] John Haviland, The Builders’ Assistant, Vol. 1 (Philadelphia, PA: John Haviland, 1818), 217–236.

[24] John Haviland, The Builders’ Assistant, Vol. 2 (Philadelphia, PA: John Haviland, 1821), 46–48.

[25] Ibid, Vol. 1, 123–132.

[26] For example, see the listing for “Plaster Master! Harry Mordecai in the Old State Capitol,” Kentucky Historical Society, online: https://www.evensi.us/plaster-master-harry-mordecai-capitol-broadway-100/360753680 (accessed 19 June 2020).

[27] Bayless E. Hardin, “The Capitols of Kentucky,” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Vol. 43, No. 144 (July 1945): 185

[28] Journal of the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, 1828 (Frankfort, KY: Jacob H. Holeman, 1828), 228; available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433004434852 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[29] Journal of the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, 1830 (Frankfort, KY: James G. Dana and Albert G. Hodges, 1830), 131; available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=7mZaAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed 29 June 2020).

[30] Acts of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, 1831 (Frankfort, KY: Albert G. Hodges, 1832), 25; available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/iau.31858018298723 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[31] Ibid, 243.

[32] Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly (Virginia), 1776–1865, Acc. 36121, Box 275, Folder 78, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[33] Frank F. Mathias, “Orlando Brown,” in The Kentucky Encyclopedia, John E. Kleber, ed. (Lexington: University of Kentucky, 1992), 130–131.

[34] “Money paid by O. Brown on account of his building,” circa 1935, p. 1, Orlando Brown Papers, Filson Historical Society, Louisville, KY.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Letter from Orlando Brown to his father, John Brown, 23 June 1836, Orlando Brown Papers, Filson Historical Society, Louisville, KY.

[37] Henry (Harry) Mordecai, Franklin County Tax List, 1816, p. 34, MSS 67, Franklin County Tax Lists, 1797–1818, Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, KY; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS3J-K97K-5?i=39&cat=155188 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[38] Francis Radcliffe, Franklin County Tax List, 1813, p. 40, MSS 67, Franklin County Tax Lists, 1797–1818, Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, KY; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS3J-K3S9?cat=155188 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[39] Harry Mordecai, Franklin County Tax List, 1823, p. 29, microfilm MIC 102, Tax Book of Kentucky Counties, Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, KY; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS3J-K97Z-J?i=513&cat=155188 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[40] Harry Mordecai, Franklin County Tax List, 1828, p. 11, microfilm MIC 102, Tax Book of Kentucky Counties, Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, KY; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS3J-K9QK-J?i=805&cat=155188 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[41] Carter G. Woodson, ed. Free Negro Owners of Slaves in the United States in 1830: Together with Absentee Ownership of Slaves in the United States in 1830 (Washington, DC: The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, 1924), 5; available online: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89058592593&view=1up&seq=29 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[42] Franklin County, Kentucky, Deed Book P, p. 351, 18 November 1834, Franklin County Courts Clerk’s Office, Frankfort, KY.

[43] Bellardo, 274.

[44] Robert Anthony Strode, History of St. John African Methodist Episcopal Church, Frankfort, Kentucky, doctoral dissertation (Lexington Theological Seminary, 2004), 14–15.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Lewis Franklin Johnson, The History of Franklin County, Ky (Franklin Co., KY: Roberts Printing, 1912), 263.

[47] Strode, 15.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Harry Mordecai, Franklin County Tax List, 1852, p. 21, microfilm MIC 6047, Tax Records, 1852–1861, Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, KY; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSLZ-K5JV?cat=155188 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[50] Mordecai empowered his executors, Jacob Swigert and Richard Gillespie, to allocate the assets between his children based on their needs. Rachel forewent her inheritance and claimed dower rights. Franklin County, Kentucky, Will Book 2, 1824–1854, pp. 240 and 244, Franklin County Court Clerk Office, Frankfort, KY; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9P3N-9XZX?i=350&cc=1875188&cat=426325 (accessed 29 June 2020).

[51] Jacqueline Ridley, “Harry Mordecai: Ancestor and Artisan,” Kentucky Historical Society website, online: https://history.ky.gov/2018/05/30/harry-mordecai-ancestor-and-artisan/ (accessed 29 June 2020).

[52] Ibid.

© 2020 Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts