In late June 1808, four identical mahogany Pembroke tables made in the joiner’s shop at Monticello were loaded onto a wagon by master joiner James Dinsmore and sent off on the three-day journey to Thomas Jefferson’s retreat Poplar Forest, then under construction ninety miles south in Bedford County, Virginia (Figure 1).[1] The story of those four tables is documented in a remarkable series of eleven letters that reveal essential elements of their design and ultimate use as envisioned by Jefferson, along with unexpected factors that affected their actual production.[2] The wealth of specific information provided by this correspondence is unequaled elsewhere in the canon of surviving Monticello furnishings and has been instrumental in the identification of two surviving tables of the four made in 1808.

The two surviving Pembroke tables are by far the best documented and earliest extant examples of furniture comprising the so-called “Monticello Joinery” group—their inclusion is irrefutable. Furthermore, unlike several other examples of Monticello joiner’s shop furniture attributed to John Hemmings, Jefferson’s enslaved African American joiner, the documentation, circumstances, and timing all suggest that these Pembroke tables were instead made by the man under whom Hemmings apprenticed, James Dinsmore.[3] In addition to specific features identified in the Jefferson correspondences, some of the tables’ construction methods are quite distinctive as well. Consequently, these two tables represent an important touchstone that can be used to help differentiate between the work of John Hemmings and James Dinsmore, thus adding definition to the somewhat enigmatic body of furniture that comprises the “Monticello Joinery” group.[4]

With the aid of Jefferson’s correspondences and other supporting documents, this article will trace the history of the tables and their connection to Poplar Forest, examine the factors that support a likely attribution to James Dinsmore, compare and contrast their distinctive construction features with a significant table by John Hemmings—which is both the only surviving piece of work that can be unequivocally attributed to John Hemmings as well as the best documented example of American furniture made by an identified enslaved cabinetmaker—and finally, explore how Jefferson may have intended to use the Pembroke tables in a creative fashion at Poplar Forest.

Ultimately, the combination of written correspondence and surviving examples of furniture provides an extraordinary glimpse into the workings of a rural plantation joinery. When contextualized, they tell a fascinating story of how three men—James Dinsmore, John Hemmings, and Thomas Jefferson—contributed to the operation and output of the Monticello joiner’s shop and the furnishing of Poplar Forest.

Introducing the Two Extant Pembroke Tables

Historian Charles L. Granquist Jr. was arguably the first to seriously study and assign potential candidates to the Monticello joiner’s shop group. Through his reading of the correspondences between Jefferson and Dinsmore, Granquist called attention to the possible existence of the Pembroke tables in 1977.[5] In 2001, a table (hereafter referred to as Table 1; illustrated in Figures 2 and 3) was given to The Corporation for Jefferson’s Poplar Forest that seemed to meet the criteria of being one of the tables described in the letters. According to Gail Pond, the collections manager and researcher at Poplar Forest, Table 1 was probably purchased at an auction sale in 1858 at Gravely Hill, a plantation located about two and one-half miles from Poplar Forest. Table 1 also carries an oral history associating it with both Poplar Forest and Jefferson. The provenance along with the very specific information contained in the letters led staff at Poplar Forest and Monticello to conclude that this was, indeed, one of the four Pembroke tables sent to Poplar Forest in 1808.[6]

In 2007, a second table (hereafter referred to as Table 2; illustrated in Figures 4 and 5) with identical dimensions and construction features came to light and was subsequently acquired by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which owns and operates Monticello. Table 2 was purchased at an antique dealer’s “tag” sale in Nelson County, Virginia. According to the Halifax County individual who sold it to the dealer, the table was found in Eastern North Carolina. Other than that, the provenance is unknown.

James Dinsmore

James Dinsmore was probably born in County Antrim, Ireland in 1771 or 1772. In 1798 he became a naturalized U.S. citizen in Philadelphia, then the seat of national government where Jefferson was serving as Vice President.[7] Little is known of his training before coming to America or even how long or where he had been working in Philadelphia prior to meeting his future employer.[8] Dinsmore must have impressed Jefferson, who hired the twenty-eight-year-old man that same year to work as the principal joiner and superintendent for the remodeling of Monticello, a project that had begun two years earlier in 1796. This immense project transformed the original house (started in 1770 but never completed), enlarging it from eight to twenty-one rooms, and adding the iconic dome.[9] Orchestrated by Jefferson, largely from afar, ten years were spent fabricating and installing virtually all the elaborate classical interior and exterior woodwork and other finish details.[10] The resulting masterpiece produced by Dinsmore and his fellow joiners and carpenters, both free and enslaved, leaves little doubt as to their abilities. Writing in 1815 to Thomas Munroe, superintendent for the city of Washington, Jefferson summarized his assessment of Dinsmore’s skill and character:

James Dinsmore and John Nielson. the former I brought from Philadelphia in 1798. and he lived with me 10. years. a more faithful, sober, discreet, honest and respectable man I have never known… both are house joiners of the first order. they have done the whole of that work in my house, to which I can affirm there is nothing superior in the US… the most difficult job you have is the dome of the Representatives, and I doubt if there be any men more equal to it than these. Dinsmore built the one to my house, which tho’ much smaller, is precisely on the same principles.[11]

According to Edmund Bacon, Monticello’s overseer from 1806 until 1822, James Dinsmore also apparently made furniture. Reminiscing in 1847, Bacon recalled:

Dinsmore, who lived with him [Jefferson] a good many years, was the most ingenious man to work with wood I ever knew. He could make anything. He made a great deal of nice mahogany furniture, helped make the carriage, worked on the University, and could do any kind of fine work that was wanted.[12]

James Dinsmore left Monticello in 1809 when the remodeling effort was essentially complete. Forming a partnership with fellow joiner John Neilson, he continued working on other prominent projects in the Virginia Piedmont including James Madison’s Montpelier in Orange County and John Hartwell Cocke’s plantation Bremo in Fluvanna County.[13] Renewing their relationship with Jefferson in 1817, Dinsmore and Neilson worked at the University of Virginia and were among the builders of the Rotunda, modeled on the Pantheon, a second-century temple in Rome. Tragically, James Dinsmore died by drowning in the nearby Rivanna River in 1830.

John Hemmings

Extensive research has been conducted on John Hemmings, who was enslaved by Jefferson, and much is known about him as well as other members of Monticello’s enslaved community.[14] Born into slavery at Monticello on 24 April 1776, John’s mother was Elizabeth (Betty) Hemmings, matriarch of Monticello’s largest enslaved family. Jefferson’s enslaved household servant Sally Hemmings was his sister. John Hemmings labored first as a field hand during childhood and then progressed to becoming an “out-carpenter” in his teens, carrying out tasks such as cutting firewood, building fences, hewing timbers, and helping to construct utilitarian log houses on the plantation.

In 1793 he began training as a joiner, working first under hired-joiner Davey Watson, to whom Jefferson had assigned him “for the purpose of learning to make wheels and all sorts of work.”[15] Hemmings received his most formative training working under James Dinsmore from 1798 to 1809. In 1799, the two men were working in the Cabinet/Library in Jefferson’s private suite, preparing and putting up the arches between the rooms.[16] By 1804 Hemmings had apparently begun working independently; a memo in Jefferson’s building notebook assigns several tasks specifically to him:

Reserved for J. Hemings. All the Chinese Railing. Venetian blinds for the Porticos. The 3. Remaing. Angular portals. the Aviary. facings of windows of covered ways[,] folds of window shutters. Closet of my bed chamber[,] store rooms in the loft.”[17]

Edmund Bacon recalled that: “John Hem[m]ings was a carpenter. He was a first-rate workman—a very extra workman. He could make anything that was wanted in woodwork. He learned his trade of Dinsmore.”[18]

With Dinsmore’s departure in 1809, Hemmings, by then a highly capable joiner himself, found himself in charge of Monticello’s joinery shop. In addition to ongoing work on the house, his duties included miscellaneous plantation tasks such as repairing harvesting and spinning equipment, making plow frames, and constructing all of the wooden parts of a convertible landau carriage. However, his most significant and best-documented architectural work is associated not with Monticello but with Poplar Forest.[19] From around 1815 until 1825 Hemmings spent a considerable amount of his time there making and installing virtually all of the exterior and interior finish work including doors and associated architraves, mantelpieces, window blinds, and all of the other elaborate woodwork specified by Jefferson and based on the Tuscan, Doric, and Ionic orders.

In a remarkably rare account of an enslaved craftsperson writing in their own voice about day-to-day activities, Hemmings described his work schedule in November 1821:

I am at worck in the morning by the time I can see and the very same at night. I have got the tow next nealy don I am bout the tow Last members Dentels and quearter round I shuld put an architrace [architrave] on the skie Light frams be four stake the scafful down it will be 16 inchs leving the first page on the frame and planting on to twelve inches this is 1/2 Inch thick and the og [ogee] Planted on it.[20]

In addition to his well-documented work as a carpenter and joiner, we also know for certain that John Hemmings made furniture; however, it is unclear just how many pieces. Furniture attributed to Hemmings can be divided into two main groups. The first group consists of furniture made for Jefferson and his immediate family for which there are specific documentary references to Hemmings’s as maker—these references prove with certainty that Hemmings was involved in cabinetmaking. The second group is based on considerations such as provenance, assumed timing for their manufacture, and specific distinctive construction details. The first group of furniture is quite small in number, comprising just eight examples. The second group is considerably larger, at one point thought to number perhaps as many as fifty examples. The factors involved in making attributions to that group are complex and in many cases conjectural to a greater or lesser degree.

There are no signed examples of John Hemming’s furniture and, as is often the case in decorative arts scholarship, critical evaluation over the years has resulted in a considerably smaller number that can be justifiably attributed to Hemmings’s hand. A full discussion of this multifaceted subject would go far beyond the scope of this article, so for the purpose at hand only the former group—those pieces of furniture for which there are concrete references—will be considered. Unfortunately, most of them have either not survived or have not yet been identified.

The eight pieces of furniture referenced in documentation are:

-

• at least two painted bedsteads[21]

-

• a round table sent to Poplar Forest in 1811[22]

-

• two dressing tables made in 1818 with the assistance of fellow enslaved woodworker Lewis[23]

-

• at least one campeachy chair sent to Poplar Forest in 1819[24]

-

• a chess table made prior to 1825

-

• a small writing desk made for Jefferson’s granddaughter Ellen Randolph Coolidge prior to 1825.

In 1856, remembering both the chess table and her small writing desk, Ellen Randolph Coolidge wrote:

He [Jefferson] had made, by his own carpenter and cabinet maker, John Hemmings, and painted by his own painter, Burwell, a small light table, divided in squares like a chess board and with a sort of tray or long box at two of the sides to hold the men and put them into as they were taken off the Board. It was a very nice, convenient little thing and purfectly answered the purpose for which it was intended. This was called one of Mr. Jefferson’s contrivances. My first writing table, made for me when I was perhaps thirteen or fourteen years old, out of the beautiful wood of the wild cherry, by the same John Hemmings, and planned by my grandfather for my use, was as simple and convenient a thing as could be, and I still remember how useful I found it as a writing table, reading desk and serving all the purposes of a light easily portable stand.[25]

The writing table, designed (“planned”) by Jefferson and made by John Hemmings may have been Hemmings’s earliest piece of furniture—Ellen was born in 1796 so, by her accounting, the writing table would have been made in 1809 or 1810, when Hemmings was in the prime of life. Tragically, the table was not destined to survive; it was lost at sea along with all of Ellen’s other personal possessions that had been shipped to Boston in 1825 following her marriage to Joseph Coolidge Jr.[26] Ellen, recalling the depth of her loss, wrote, “My books, my work box, my writing desk, the presents of my friends, my papers of every description… Every thing was lost! What bitter tears I shed over the wreck!” If anything, Hemmings was even more devastated than Ellen. In a rare, perhaps even singular, acknowledgment of and empathy for the feelings of one of his slaves, Jefferson wrote his granddaughter:

We have heard of the loss of your baggage and the vessel carrying it, and sincerely condole with you on it… John Hemmings was the first who brought me the news… He was au despoir! That beautiful writing desk that he had taken such pains to make for you! Everything else seemed as nothing in his eye, and that loss was everything. Virgil could not have been more afflicted had his Aeneid fallen a prey to the flames. I asked him if he could not replace it by making another? No. His eyesight had failed him too much and his recollection of it was too imperfect.[27]

The pride Hemmings took in Ellen’s desk and his despair over its loss is poignantly apparent. In equating his feelings with how Virgil might have felt had his epic poem, the Aeneid been destroyed by fire, Jefferson offered Hemmings a worthy tribute. To help alleviate her pain over the loss, Jefferson gave Ellen and her husband an extraordinary replacement: Describing this gift, Ellen tells us, “I sent you some years ago a copy of a letter which he [Jefferson] addressed to Mr. Coolidge at the time he sent him the Desk on which was written the Declaration of Independence. This was given as some compensation for what I had lost.”[28]

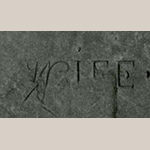

Hemmings’s final task was unrelated to either cabinetmaking or architectural joinery. In May of 1830 his wife Priscilla died. More than a year later, Jefferson’s granddaughter Cornelia wrote to her sister Virginia of going to Monticello where she found, “daddy cutting a head stone to put at mammy’s grave”[29] (Cornelia and other Jefferson family members affectionately referred to John Hemmings as “daddy.”) This slate grave marker was found on the grounds of Monticello, no longer in its original location, in the late 1950s or early 1960s. The exact circumstances of its discovery are unknown. But she was apparently buried in an as yet undiscovered graveyard somewhere on the plantation. The inscription reads, “The sed is placed at the hea[d] of my dear affectionat[e] wife Priscilla Hemmings departed this life on Friday the 7th of May 1830 ag[e] 54” (Figure 6).

By any measure the headstone is an extraordinary artifact and must be considered as important as any piece of woodwork that John Hemmings made in his career. To help put the headstone into context, in most cases, the burial grounds of enslaved African Americans at Monticello and elsewhere were rarely marked in durable ways. Today, most are only discernible by shallow depressions in the ground, almost invariably facing east. In some cases, upturned stones marking the head and foot are found marking the grave. Rarest of all are graves marked by inscribed stones.[30] In nearly all surviving cases, the inscriptions, while poignant, are quite crude in their execution. On the other hand, the quality and character of the carving executed by Hemmings for Priscilla’s gravestone is remarkably sophisticated: Note the classical Roman form of the lettering (Figure 7); the touching flourish for the “W” in wife (Figure 8); the superscript “th” in “7th” seemingly mimicking Jefferson’s own signature (Figure 9). The headstone poses numerous questions: what did Hemmings mean by the word “sed?” Where did he learn the craft of classical lettering? Where did he obtain stone-carving chisels?[31] Why does the font change to lower case in some instances? Why are letters such as the “d” in “head” missing? For now, however, it is perhaps enough to simply illustrate the headstone and let it speak for itself as another documented and undeniable example of Hemmings’s craftsmanship.[32]

Of the eight pieces of furniture referred to in the documents, it is the round table sent to Poplar Forest in 1811 that is of primary importance. Writing from Poplar Forest in December of that year, Jefferson instructed Edmund Bacon to “tell Johnny Hemmings to finish off immediately the frame for the round table for this place.” An undated drawing by Jefferson’s granddaughter Cornelia while at Poplar Forest depicts what is believed to be this table, along with a Windsor chair (Figure 10). Crafted of cherry, as was Ellen’s writing table, this revolving-top circular table (Figure 11) has a provenance linking it to Poplar Forest through descendants of the Cobbs-Hutter family who purchased Poplar Forest from Jefferson’s grandson, Francis Eppes, in 1828. Although Jefferson’s instructions are ambiguous—he tells us only that Hemmings made the frame—it seems very likely, lacking evidence to the contrary, that he made the top as well.[33] It is both the only surviving example of furniture that can be definitively documented as being made by John Hemmings and the best documented example of American furniture made by an identified enslaved cabinetmaker. Close analysis and comparison of Hemmings’s table with the Pembroke tables provides a remarkable and unprecedented window into the dynamics and operations of a rural plantation woodworking shop. Through such investigations we can also begin to differentiate John Hemmings’s hand from that of James Dinsmore and others who worked in the joiner’s shop at Monticello.

Under the terms of Jefferson’s will, John Hemmings was freed in 1827, one year after Jefferson’s death. Although he was given “all the tools of his trade,” with the possible expectation that he would continue to ply his trade as a freed man, Hemmings instead elected to remain at Monticello with his family until his own death in 1833.

The Letters Documenting the Pembroke Tables

On 12 October 1807, President Jefferson, writing to Richmond joiner James Oldham from Washington, drafted the first letter in a series spelling out key aspects of the tables he had in mind, in particular the dimensions and wood needed for the tops:[34]

I have a job of 4. Pembroke tables on hand at Monticello, but we have not the Mahogany for the tops. they are to be 2f 3I. square in the bed, & the leaves half the breadth of the beds, so as to be 4f-6 by 2f. 3 when the leaves are up. 2 planks of Mahogany 10.f. by 2f 4I each would make the tops of the 4. tables. will you be so good as to chuse & procure for me 2. planks of <that> 2f. 4I. by 10f. of very fine mahogany and forward them to Monticello by the boats addressed to Mr. Higginbotham who will pay the carriage. I name 2.f.4.I. for the width that they may work to 2f. 3I. clear [clean?]. let me know the cost and it shall be immediately remitted to you.[35]

Jefferson’s initial letter to Oldham in 1807 reveals nearly everything we need to know about his intended design. The most striking aspect is the exceptional twenty-seven-inch width of the “very fine mahogany” he had in mind for the “beds” or main top boards. But there are no less than ten subsequent letters that reveal additional aspects to the remarkable story surrounding these four tables.

On 11 December that year, James Dinsmore, already aware of the plans to produce the tables, wrote one of his regular reports to Jefferson about the progress of work at Monticello and advising: “when you order the Mahogany for the tables it will be necessary for you to include enough to make the Sashes that are wanted for the house here, viz 2 double and one treble window which will take two planks 10 f 6 long 14I wide and 1 1/2 I thick.”[36]

Just four days later the President responded from Washington, apparently reminded by Dinsmore’s letter that he had not heard back from Oldham: “I recieved [sic] yesterday yours of the 11th. I wrote to mr. Oldham on the 12th. of October for mahogany for the tables, & took for granted it was gone on but as I have not heard from him. I will write again to-day, as to that as well as the additional quantity, you want… .”[37]

Predictably, another letter went off to Oldham reiterating his original order along with a request for the extra mahogany needed for the window sashes:

By a letter of Oct. 12. I asked the favor of you to purchase for me in Richmond & forward to Monticello by the boats as much fine mahogany as would make me 4. Pembroke tables 2f 3 I. by 4f.6.I. that is to say, the beds 2f. 3I. square and the leaves 13 ½ I. by 2f.3I. not having heard from you since, I have feared my letter may have miscarried, & therefore I now repeat the request, with the further one, that you will add to this about 30. square feet of mahogany 1 1/2I. thick, & fit for sashes, of course strait grained. planks of 10 ½ f. long will cut to best advantage as to the lengths of the sash bars. I will thank you to let me hear from you on this subject.[38]

He emphasized, again, that the wood for the tables was to be “fine mahogany,” putting extra emphasis on “fine” by underlining it. Oldham’s reply, written Christmas Eve 1807, explained the circumstances for his delay in responding and included a bill detailing what he had been able to find:

Your Letter of the 15 Instant was this morning handed me by Mr. Gibson, its reference to one of the 12 October realey Surprisd Me… the Poast Office had sent the Letter to my house the day after I set oute for Amherst-Countey. my return from thence was Aboute the 12th of November, when I Perceivd it nesary [necessary] for me to repair immediately to Suffolk whare I was detained for 3 weaks, and this morning I had just ariv’d from Petersburge.

43-4I. of San demingo wood

31-8- of Bay: —— do 1 1/2 I.

75-0 at 3/. foot. ===== $37.50the two Planks for Tables measurs 27I. at one end and 26I. at the other by 10-3I. Long I could not possibelly finde any wider and supposed this could be made to answer, it is very nice and solid. there is very Little of San demingo wood made use of heare, the 1 1/2I. Plank is Bay wood and very good for the Perpose intended I have it nicely cased in a box so as it shal not receive any dammage in the carrage -and I expect a conveyance about Munday next… .[39]

Unfortunately, although the planks were long enough, they were narrower than what Jefferson wanted by one inch at the wide end and 2 inches at the narrow end. He took Jefferson’s specification for “very fine mahogany” to mean “San demingo wood.” Santo Domingo mahogany, prized during the mid-eighteenth century for its dense rich character and ability to hold finely carved detail, apparently had fallen out of favor as “there is very Little of San demingo wood made use of heare.” On the other hand, Oldham was sending “Bay wood” (Honduras mahogany) for the window sashes.[40]

The Santo Domingo mahogany arrived at Monticello by 3 January 1808. Jefferson, apparently for the benefit of James Dinsmore, carefully transcribed the portion of Oldham’s letter detailing what had been sent, adding at the top: “Mahogany forwarded to Monticello by Mr. Oldham.” He also penned a brief memo with specific instructions for Dinsmore at the bottom, emphasizing the importance of the dimensions as originally specified, suggesting a solution and also giving us a hint concerning his plans for them: “ThJ to mr. Dinsmore — Altho’ the breadth of the above table planks is scanty and may occasion a little piecing in some of the leaves, we must not depart from the size of the table 2f. 3.I. by 4f. 6I. as that connects them with the tables they are to be used with.”[41]

About six months went by during which the tables were completed. On 7 June 1808, in a lengthy memo to overseer Edmund Bacon with instructions for numerous other plantation tasks, Jefferson added: “As soon as the sashes are ready for Bedford, furnish Mr. Randolph 3 of your best hands, instead of his waterman, who are to carry the sashes, tables, and other things up to Lynchburg, and to give notice of their arrival to Mr. Chisolm, who will then be in Bedford, and will have Jerry’s wagon there… .”[42] This is the first mention of Jefferson’s intention to use the tables at Poplar Forest not Monticello. About two weeks later, on 24 June, James Dinsmore wrote Jefferson:

I have packed up to go with the waggon, this day for P F [Poplar Forest], 4 tables 2 matrasses [mattresses] 2 oznaburg [osnaburg] beds 2 bolsters & pillows 2 pair of sheets–2 stoves [57?] metal Sash wts [weights] and 12 pieces of sheet iron and a small peice [sic] of sheet lead for the gutters–we Concluded it best to send the tables and beds by the wagon – as the Sashes will not be ready before harvest.[43]

We also get a hint that Jefferson may have been planning an upcoming visit to Poplar Forest; in addition to the tables, bedding and stoves were also being sent.

Finally, on 30 June 1808, Bacon wrote Jefferson confirming that the wagon had departed: “Jerry Left heare Last satterday set of for Bedford with a Load of the articles you Directed to go by him… .”.[44]

The Pembroke Tables and Poplar Forest

Other than perhaps some make-do accommodations for the workmen, the Pembroke tables were the first real furnishings for Poplar Forest. When they arrived in late June 1808 the house was no more than an un-finished brick shell. The roof framing and sheathing had just been completed the previous December. There were no sashes in the window openings. Flooring was only installed in some of the rooms. None of the finish woodwork had been started. Even some brickwork was still going on.[45]

Anticipating Jefferson’s visit, Hugh Chisholm, Jefferson’s brick mason, summarized the progress and promised that he’d have Jefferson’s bed alcove finished in time for his arrival. “Mr. Perry has laid the flow [floor] in west rooms and is now studing the alcove, as soon as he is done that I shall bricknog and plaster it for your reception.”[46]

As it turned out, an accident prevented Jefferson from making the trip. Writing to Chisholm on 8 September 1808, he related the circumstances: “I had intended to have been at Poplar forest before this time, but a hurt which I received in riding confined me to the house a considerable time and leaves me not yet strong enough to undertake a journey and as I am to set out for Washington about the 27th I think it extremely doubtful whether I shall be able to go to Bedford at all, however anxious I am to do so… .”[47] Presumably the tables, bedding, and stoves were stored away to await Jefferson’s eventual arrival.

Jefferson would not visit Poplar Forest until more than a year later. In November 1809, following his retirement from the presidency the previous March, he finally arrived for his first stay in the partially finished house. By then the brickwork had been completed and the sashes had finally been finished and presumably installed. But little else had been done, at least on the inside. From then on, up until his last stay in 1823, he would visit Poplar Forest two to four times a year staying for two to eight weeks at a time.[48]

By 1815 the house had apparently become much more livable. One indication is Jefferson’s tax declaration for “Property in Bedford and Campbell Counties.” In that year, a so-called “luxury tax” was imposed by the Commonwealth of Virginia to help defray costs associated with the War of 1812. There were various categories for luxury items, one being “pieces made in whole or in part of mahogany.” So, in addition to slaves, land, and livestock, “4 Pembroke tables, say teatables mahogany” are listed along with a “3 parts of Dining tables” and “4 bookcases with mahogany sashes.”

Property in Bedford and Campbell taxed by the state D.C.

46 slaves of 12 years old & upwards @80 cents 36.80

Or 9 years and under 12 @50 “ 10.50

12 horses and colts @21 “ 2.52

39 cattle @ 3 “ 1.17

4 bookcases with mahogany sashes @50 “ 2

3 parts of Dining tables mahogany @25 “ .75

4 Pembroke tables, say teatables mahogany @25 “ 1.

3790 acres of land @ 85 cents on the 100 D. value

A dwelling house (of more than 500 D. value)(signed) Th. Jefferson Monticello, Feb. 11, 1815[49]

Of course, the few pieces inventoried in 1815 were not the sole furnishings of Poplar Forest in 1815. Jefferson made a brief notation to himself that “beds, bedding & kitchen furniture is exempt, & where the rest of the furniture of a house does not exceed 200.D. it pays nothing. I consider my furniture at Poplar Forest as under that value, but of this the assessor will judge for himself on an examination of the furniture.”[50] So there was certainly other utilitarian furniture, much of it probably plantation-made. In the summer of 1816, Jefferson’s granddaughters Ellen and Cornelia visited Poplar Forest for the first time.[51] Ellen, reminiscing long afterwards, provided additional insights into the furniture that was there: “It was furnished in the simplest manner, but had a very tasty air; there was nothing common or second-rate about any part of the establishment, though there was no appearance of expense.”[52] This description certainly seems consistent with the Pembroke tables as well as the circular table made by John Hemmings, which would have been there as well.[53]

Jefferson’s grandson Francis Eppes, who had begun living at Poplar Forest in 1823, inherited the house following his grandfather’s death in 1826. Yet only two years later in 1828 he sold the property along with at least some of the furnishings, which may have included the four Pembroke tables.[54] A disastrous fire gutted Poplar Forest down to the brickwork in 1845; however, the fire apparently consumed the house slowly enough to allow all of the furniture remaining after the 1828 sale to be saved.[55]

Physical Details of the Two Pembroke Tables

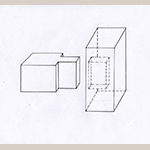

The two surviving Pembroke tables are alike dimensionally, varying no more than an eighth of an inch in any of their measurements. Furthermore, they exhibit construction details so distinctive that there is no question they were made by the same hand. This unmistakable similarity adds further credibility to both—they are clearly part of a set.

How do the dimensions and wood used in these two tables match the dimensions provided by Jefferson versus the stock that he received from James Oldham? To begin the comparison, the condition of both tables, especially the tops and leaves, needs to be described because each has seen a hard life.

Table 1 has had its leaves re-hinged with different hinges in three different locations. Even so, portions of what may be the original hinges survive. Although the top and the leaves are original, the top board seems to have been slightly reduced because the adjoining edges are squared and lack rule joints, which are typically found on drop-leaf tables to give a more finished appearance by presenting a thumb-molded edge while hiding the hinge knuckles.[56]

Table 2 has also had its share of problems. As found, both original leaves were missing and had been improperly replaced with new mahogany stock poorly matched to the original top. The whole table had also been refinished, perhaps at the same time the leaves were replaced. The hinge seats on the underside of the top exhibit several generations of screw holes indicating multiple episodes of re-hinging, albeit in the original locations. There were also breakouts at all hinge locations where the barrels of the hinges are mortised into the underside. Most importantly, Table 2 does have male rule joints cut onto the edges of the original top board, suggesting that the tops on both of these tables were originally handled in the conventional, more formal, manner.[57]

Both tabletops measure exactly 26-7/8 inches in length so they are within an eighth of an inch of the two foot, three inches (twenty-seven inches) specified by Jefferson. Importantly, they are both made of single boards of Santo Domingo mahogany. But rather than being the full twenty-seven inches wide as Jefferson desired, the top on Table 1 is twenty-five inches wide and Table 2 is wider by half an inch, including the surviving male portion of the rule joint. The leaves on Table 1 are 12-1/2 inches wide and would have been wider by about a quarter of an inch or so before the female portions of the rule joints were cut off. Factoring in waste, the planks received from Oldham would have conveniently yielded finished boards corresponding to these same measurements.

The question is whether Jefferson would have settled for compromising on the overall dimensions of the tables. Although the length is within an eighth of an inch of the specified “2f 3I,” the width of the “bed,” at only twenty-five inches, is two inches shy. Furthermore, an additional two inches is lost in the overall length of the table when including the leaves, which are only 12-1/2 inches rather than 13-1/2 inches as specified. Thus, if both tables had 12-1/2-inch leaves originally, they would have each measured just four feet, two inches long plus a fractional amount for the slight gap between the leaves and the top.[58] This is far short of the “4f 6I.” Jefferson was so adamant about. But the solution of gluing two-inch strips onto the edges of each of the leaves (remember that Jefferson told Dinsmore “it may occasion a little piecing in some of the leaves” not the “beds”) to achieve the four foot, six inch overall length would surely have been visually distracting, if, in fact, there was any additional mahogany at hand. Unfortunately there are no subsequent letters between Dinsmore and Jefferson indicating what was ultimately done.[59] As it turned out, however, Jefferson was able to get away from Washington in the spring of 1808 and spent a month at Monticello from May 8 to June 8.[60] If the tables were still under construction at that time it is possible he and Dinsmore conferred directly about the problem and reached an understanding. In any case the dimensions, as specified, were compromised.

While the single-board Santo Domingo mahogany tops and the unusual proportions are enough alone to make these tables instantly recognizable, both also are identical when viewed from the underside (Fig. 3 and Fig. 5). Most evident at first glance are the screws used to assemble the inner rail/leaf-support rail system (see Figure 12 for table construction terms).[61] This is one of three distinctive details used to construct the tables. The inner rails lap onto and are screwed to the legs (Figure 13) and then, rather than nailing them to the leaf support rails from the inside as was commonly done, additional screws are instead driven through the leaf-support rails into the inner rails from the outside uniting the two elements (Figure 14). This rather tidy (and solid) method with extensive use of screws may relate to the construction of the Monticello Parlor parquet floor, a task assigned to James Dinsmore in a memo dated 24 September 1804 and completed about 1805 (Figure 15).[62] There, the individual squares are composed of a beech-wood frame with a contrasting center panel of cherry; but instead of laborious traditional mortise and tenon joinery, Dinsmore assembled the frames with simple mitered half-lap joints secured with two screws at each corner from the underside (Figures 16 and 17).[63]

The second distinctive detail relates to the tenons that join the main end rails and side leaf support rails to the legs—rather than using conventional tenons centered in the stock with a shoulder on either side (Figure 18), single-shouldered tenons are employed (Figure 19) thus halving the number of saw cuts necessary. Although frequently used for chair and table stretchers, this type of tenon is highly unusual for the primary joints in table-frame construction. And, rather than breaking up the four-inch-long joint into two separate joints, as would be expected, a single full-length tenon is used instead. (See Figure 20 for an exploded view of the rails-to-leg construction.)

Lastly, the main front and rear rails are set back slightly from the legs rather than flush (Figure 21). This feature, although admittedly not unique, eliminated the need for perfect alignment between the two elements so the work would not need to be as exacting because slight variations would be unnoticeable.

Considered together, these three construction methods—the use of screws, single-shouldered tenons, and offset rail/leg joints—all suggest a “streamlining” or simplification of the construction process, which would help cut down on the time needed without sacrificing any integrity of the finished product.

There are also additional features exhibited by the Pembroke tables that are particular to furniture making and a cabinetmaker’s skills. To begin, they are drop-leaf tables, which require specialized hinging of the leaves along with a wooden-hinged leaf-support system, both of which require skill and practice to execute. In addition to screws set into screw wells, neatly beveled glue blocks were used to help secure the tops.[64] More vertical glue blocks, none of which survive, originally served to further unite the fly-rail backing rails to the legs. But before the glue blocks were applied, the inner rail surfaces were prepared with a toothing plane, an unexpected, and indeed remarkable, detail considering the plantation-made context (Figure 22).[65] In another slightly surprising departure from simple joiner’s work, the rail/leg joints are unpinned, relying on glue alone to secure them. One final feature gleaned from Table 1, although minor, is worth mentioning for the record: pins inserted into the undersides of the leaves act as stops for the fly-rails (Figure 23).

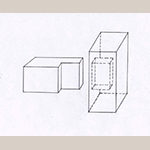

The Pembroke Tables Versus the Circular Table Attributed to John Hemmings

Since it can reasonably be assumed that the Pembroke tables were made by either James Dinsmore or John Hemmings, how can their work be differentiated? The frame (Figure 24) for the revolving-top, circular cherry table attributed to Hemmings (Fig. 11) provides an excellent benchmark for his work at nearly the same time as the Pembroke tables were made. Both the Pembroke tables and the circular table frame were made for Poplar Forest, making the comparison particularly appropriate.[66]

A comparison of basic joinery details immediately reveals that the construction of Hemmings’s table frame shares nothing in common with that of the Pembroke tables: Most apparent are Hemmings’s flush rail/leg joints as opposed to the offset joints utilized for the Pembroke tables. Hemmings also chose traditional double-shouldered tenons centered on the stock rather than the single-shouldered tenons used for the Pembroke tables.[67] And finally, Hemmings opted to pin the joints of his table frame rather than leaving them unpinned as is the case with the Pembrokes.[68]

All in all, a case could be made for assigning the Pembroke tables to James Dinsmore based on these physical aspects alone. When the additional weight of the documentary record is added, the evidence in support of a Dinsmore attribution becomes nearly overwhelming: Jefferson communicated directly with Dinsmore regarding the specifics of the Pembroke tables’ production, telling him that “we must not depart from the size of the table 2f.3.I. by 4f. 6I” and that “a little piecing in some of the leaves” may be necessary.

Jefferson was also usually quite specific about assigning work, often relaying his expectations through either Dinsmore or Edmund Bacon. If Jefferson had intended for Hemmings (or anyone else) to make the tables, it seems likely it would have been noted in his instructions. We also know that Dinsmore was aware of the table project well before the mahogany was finally delivered as he refers to “the Mahogany for the tables” in his 11 December 1807 letter. In addition to evidence from the correspondence, we know Dinsmore was working specifically with mahogany; as Edmund Bacon recollected, “he made a great deal of nice mahogany furniture.” Indeed he may have had in mind these tables as he was charged with making the initial arrangements for shipping them. And while it cannot be ruled out that Hemmings may have had a hand in their construction, the 1804 work memo of independent tasks suggests that by that time, he had advanced beyond merely serving as Dinsmore’s helper.

It is unknown why Hemmings chose not to adopt for his table the primary construction details favored by Dinsmore. As noted earlier, he may well have been fully involved with his own assigned tasks and may have had little or no association with the project of making the Pembroke tables, instead using another table at Monticello as a model for the construction of his circular table. Or, another possibility is that he may have been trained in basic furniture joinery prior to Dinsmore’s arrival in 1798 while working under Davey Watson beginning in 1793 “learning to make wheels and all kinds of work.” Interestingly, Watson is known to have made furniture (see Endnote 15). In any case, these differences allow some important and potentially useful distinctions to be drawn between Dinsmore and Hemmings, at least in terms of their approach to table construction.

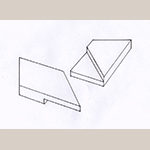

Jefferson’s Geometrical Possibilities for the Pembroke Tables

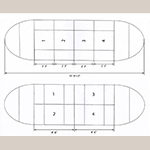

The precise dimensions specified by Jefferson present a number of different possibilities from the geometrical perspective; the tops were to be perfectly square with leaves exactly half their width. We know that these Pembroke tables were originally intended to be mated with other tables because Jefferson refers to “the tables they are to be used with.”[69] Jefferson may have had more in mind than simply enlarging an existing set of tables with these new Pembroke tables. After all, if this were the only aim then the logical solution would be to simply add ordinary drop-leaf tables of the same length. Although it is admittedly presumptuous to try and second guess Jefferson, there is little doubt that he was intrigued by various geometric shapes such as squares, cubes, octagons, and ellipses as well as more complex geometric designs such as the parquet floor patterns that he had seen in France. And, given his geometric nature, it is plausible he had in mind various geometric combinations for using Pembroke tables.[70]

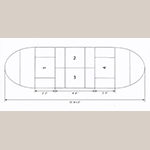

Probably long before Jefferson conceived of the tables, he was sketching plans for extending a two-part elliptical table with additional modular elements. An undated drawing depicts two halves of an elliptical table split along the long axis and united by three “units” thereby extending the overall length (Figure 25).[71] It is unclear whether these are simply additional leaves or actual tables but, in any case, his sketch (perhaps coincidentally, perhaps not) calls for these supplemental extension units to be exactly the same length as that specified for the Pembroke tables—four feet, six inches. Note that these extra sections are positioned so as to be cross-grained to that of the elliptical ends with three of them, each two feet, one inches wide, combined so as to align with the overall length of the long axis of the elliptical ends, which are six feet, three inches long. On the reverse side is another, more cryptic, sketch (Figure 26).[72] In this version elliptical ends, this time bisected laterally, are combined with square units.

These two sketches may be embryonic versions of what Jefferson envisioned for the Pembroke tables. And, in fact, Jefferson owned a two-part elliptical table (Figure 27).[73] This very unusual table, owned privately and reproduced for Monticello in 1993, was clearly inspired by tables he saw while traveling in Holland in 1788 and sketched in the margin of a letter along with notes detailing their construction (Figure 28):

Dining tables letting down with single or double leaves so as to take the room of their thickness only [-] with a single leaf, when open thus [sketch of three-legged table with two main and one swing leg] or thus [sketch of four-legged table with two main and two swing legs] [slash] double leaves open [sketch of table with a swing leg on either side].[74]

Underneath are additional sketches that show each version with the swing legs folded into the frame. The construction of the surviving table is consistent with the sketch depicting the double-leaf version except that it has two swing legs on one side and one on the other rather than just single legs on either side (Figure 29, left). Each section folds down to a thickness of just four and one-half inches (Figure 29, right), enabling them to be stored away compactly when not in use.[75] When the two double-leaf ends are combined and fully open, the entire table measures six feet, nine and one-half inches long. Most importantly, however, the tables are exactly four feet six inches wide where they join in the middle, which corresponds precisely with the dimension of the Pembroke tables with the leaves up as originally specified by Jefferson (Figures 30 and 31).

Recalling again Jefferson’s instructions to Dinsmore that “we must not depart from the size of the table 2.f 3I. by 4f 6I. as that connects them with the tables they are to be used with” it is clear that both dimensions were critical: the depth and the overall length. This factor thus leads to a refinement of the scheme he sketched out (Figure 32), resulting in two main options for using the Pembroke tables depending on how they are oriented: Option One has all four tables, each four feet, six inches long with the leaves up, placed perpendicular to the elliptical ends (Figure 32, upper plan). This arrangement results in a series of perfect squares marching down the center flanked by rectangles half their width framing the sides. The grain direction of the tops is perpendicular to that of the ends in a similar fashion to that shown in Fig. 25. This arrangement introduces another possible intent by Jefferson beyond the mere arrangement of geometric forms: wood reflects light differently depending on its orientation and on the viewing angle. This factor is another aspect that can be linked, in a way, to the parquet floor—the grain direction of the cherry panels alternates on adjacent squares further enhancing the visual effect.[76] With Option One, a single table, or two, three, or all four tables could be used depending on the overall length desired.

Option Two rotates the Pembroke tables ninety degrees: all four tables (each two feet, three inches wide) could be lined up, two deep, with the grain running parallel to that in the ends (Figure 32, lower plan). This option results in an entirely different geometric effect and could only be used with either two or four tables. Option Three is a hybrid arrangement combining both Option One and Option Two resulting in alternating grain direction of the Pembroke tables with tables one and four running perpendicular to the ends and tables two and three running parallel (Figure 33). The play of light upon the different surfaces would be maximized with this version.

Finally there is Option Four: all four tables could be used with the leaves down resulting in shorter overall length (Figure 34). This option, although suggestive of the scheme depicted in Fig. 26, would result in gaps in the tabletop because of the folded-down leaves. Nor would this arrangement work if the Pembroke tables were rotated ninety degrees, owing to the additional overall length resulting from the thickness of the folded-down leaves as well as their interference with seating.

This full set of four optional arrangements is only possible if the length of the tables matched Jefferson’s specifications, which we know was not the case. Because the tables ultimately ended up being only four feet, two inches long (instead of four feet, six inches), the number of arrangements was reduced to just two possibilities, both versions of Option Two. Either all four or just two of the tables could be used, both with the same orientation (Figure 35). While the effect on the overall length of the resulting table would have been minimal (only eight inches), the geometric possibilities would have been limited to this one rather unpleasant configuration in which the arrangement of perfect squares and rectangles is lost; the main tops, rather than being exactly twenty-seven inches square, are instead twenty-seven inches by twenty-five inches. Nor could they have been arranged to take advantage of the different visual effects by placing them cross-grain to the ends since their overall length was too short. In summary, by designing these smaller Pembroke tables that could be aligned in both orientations with the other tables, Jefferson may have envisioned several different options for geometric and visual effects, in addition to being able to use them individually as conventional Pembroke tables, or “teatables.”

Adding another layer to the discussion, however, is the fact that Jefferson commissioned five single-leaf versions of the tables he had seen in Holland to go along with the two double-leaf elliptical ends. His 1815 tax declaration for personal property at Monticello lists “5. Single & 2 double leaved dining tables.” The tables were still at Monticello in 1826 at the time of Jefferson’s death; an inventory of the house by his daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph notes “Mahogany Dining table in 7 pieces” in the Dining Room.[77] Recent research by Diane Ehrenpreis, Monticello’s associate curator, indicates these tables were made by the New York cabinetmaker Thomas Burling in 1790. Ehrenpreis’s conclusion is based on the recent discovery of a packing list of furniture and other items shipped from New York in 1790, which lists “Dining tables” along with crate dimensions that correspond nicely with the space needed for all seven tables folded compactly.[78] This dining arrangement, rather than incorporating either conventional free-standing tables or an expansion mechanism with drop-in leaves to extend the seating capacity, used single-leaf tables—which were just that, individual single leaves supported by bases having two stationary legs and one swing leg as illustrated in Fig. 26. And, if dimensioned accordingly (two feet, three inches wide by four feet, six inches long), Jefferson could have been orienting them either parallel to the elliptical ends or perpendicular to them in a similar fashion to what he sketched in Fig. 25.[79] Unfortunately, none of the single-leaf tables have been located.

It is possible Jefferson was considering an alternate, even more inventive, scheme using the Pembroke tables with the elliptical ends instead of the single-leaf tables. On the other hand, he may have been contemplating combining them with entirely different tables. In any case, the same set of options holds. With that in mind, just how Jefferson may have intended to use the Pembroke tables at Poplar Forest is perhaps more important than which specific tables he wanted to use them with.[80]

Conclusion

Of all the furniture associated with the Monticello joiner’s shop the four rather humble Pembroke tables (Fig. 2 and Fig. 4) made in 1808 by James Dinsmore occupy a uniquely important place in terms of the depth of their documentation. While a full accounting of James Dinsmore’s furniture output remains elusive, Edmund Bacon’s reference to his producing “a great deal of nice mahogany furniture” certainly suggests there may have been more. These Pembroke tables represent at least a start in providing some details that may help in crediting other pieces to his hand.

Just as importantly, structural analysis of these tables allows us to differentiate the work of Dinsmore from that of his former apprentice, the enslaved woodworker John Hemmings. Hemmings’s round revolving-top table (Fig. 11) is the best-documented example of American furniture made by an identified enslaved cabinetmaker and is crucially important to current and future scholarship about African Americans in the decorative arts. While the combination of specific documentary references and provenance can point to only the single table by Hemmings at this time, it provides us an important starting place to discern his work from that of others—free and enslaved—at Monticello.

Finally, the extraordinary correspondence associated with the Pembroke tables tells not only the fascinating story of their creation and the circumstances that compromised Jefferson’s expectations for them, but also suggests some novel schemes he apparently had in mind for modular dining tables. Indeed, it also cannot be ruled out that Jefferson may have also had a hand in specifying some of the idiosyncratic construction details used to build the Pembroke tables, as he was inclined to involve himself in all aspects of his projects. It is perhaps an unfinished story as we are reminded that there may be two more Pembroke tables—mates to the others—waiting to be discovered.

In conclusion, the story that has emerged sheds light on the contributions of three men, James Dinsmore, John Hemmings, and Thomas Jefferson, and provides us an unparalleled look into the dynamics of a single plantation workshop. It is not often that we can distinguish between the various craftspeople at work or know what the consumer wanted and the role that they played. The fact that the three men involved in designing and creating these five tables for Poplar Forest were an immigrant, an enslaved man, and a President of the United States is truly extraordinary.

Robert Self is the Robert H. Smith Director of Restoration (retired) at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. His is grateful to William L. Beiswanger, Diane Ehrenpreis, Emilie Johnson, Travis McDonald, Gail Pond, and Susan R. Stein for their extremely helpful comments and suggestions. Special thanks also go to his wife, Ruth L. Ewers for her objective input as a non-furniture person. He can be reached at [email protected].

[1] In 1806, before he had even completed building Monticello, Jefferson already felt the need for a separate retreat away from, in the words of his earliest biographer Henry Randall, “the hotel-like bustle and want of privacy at Monticello.” Jefferson personally laid out the foundation for the unique octagonal house in early August of that year and the building process began in early January 1807 with brick mason Hugh Chisholm digging clay for the bricks; by June of that year brickwork had already progressed to the point where he was ready for the window and door frames. For an extensive history of Poplar Forest, see S. Allen Chambers, Poplar Forest and Thomas Jefferson (Little Compton, RI: Fort Church Publishers and The Corporation for Jefferson’s Poplar Forest, 1993).

[2] This group of letters is somewhat obscure. All are held by the Massachusetts Historical Society’s Coolidge Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts, the second largest Jefferson collection in the country. None of them have been formally published. The date range, 12 October 1807 to 30 June 1808 falls beyond the most recent volume (Vol. 43: 11 March to 30 June 1804) published by Princeton University in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson series and just before the inaugural volume of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series (sponsored by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and published by the Princeton University Press) which begins with Jefferson’s retirement on 4 March 1809.

[3] Note that although most all Hemings family members have historically spelled their last name with one “m,” John Hemmings tended to use two “m’s” when signing his name. Monticello historians now follow John Hemmings’s practice.

[4] As far as is known, Jefferson never used the word “joinery” to refer to the plantation shop, instead referring to it as the “joiner’s shop.” For this reason, historians at Monticello now use the phrase “Monticello joiner’s shop” rather than “Monticello Joinery.” For an overview of Monticello-made furniture see Susan R. Stein, The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello (New York: Harry Abrams and Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, 1993), 273–299; Robert Self and Susan R. Stein, “The Collaboration of Thomas Jefferson and John Hemings,” Winterthur Portfolio 33, No. 4 (1998). As is often the case with ongoing research, the reader should be aware that current thinking has changed in some respects since these were published.

[5] Charles L. Granquist Jr. (Monticello Assistant Director/Curator [1973-1985]), Cabinetmaking at Monticello (Master’s thesis, State University of New York at Oneonta, 1977), 19-21. This thesis was the first scholarly in-depth study of Monticello-made furniture. It was through the author’s reading of this source that he became aware of these tables.

[6] Robert L. Self, unpublished furniture examination report, Thomas Jefferson Foundation Curatorial records, 20 October 2003.

[7] K. Edward Lay & the Dictionary of Virginia Biography, James Dinsmore (1771 or 1772–1830), Encylopedia Virginia, online: https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Dinsmore_James_1771_or_1772-1830 (accessed 17 April 2020).

[8] Congress passed the Naturalization Act in 1790. Immigrants who had resided in the country for two years and kept their current state of residence for one year were eligible for citizenship. So Dinsmore must have been in America for at least two years and Philadelphia for one year before being naturalized there in 1798.

[9] Writing to Comte de Volney on 10 April 1796 apologizing for the condition of Monticello, Jefferson wrote, “…I regret that I am in a situation which will not leave us either in the quiet or comfort we might desire. My house, which had never been more than half finished, had during a war of 8. years and my subsequent absence of 10. years gone into almost total decay. I am now engaged in repairing altering and finishing it.” Thomas Jefferson Papers 1606–1943, Reel 20, Series 1, General Correspondence and Related Material, 1651–1827, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

[10] Throughout most of the period of the remodeling, Jefferson was away from Monticello serving as Secretary of State (1790–1793), Vice President (1797–1801), and finally as President (1801–1809). Jefferson wrote Dinsmore regularly with instructions for him as well as for other workmen. It is due to this body of correspondence that we know so much about the construction of Monticello.

[11] “Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Munroe, 4 March 1815,” Founders Online, National Archives, online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-08-02-0247 (accessed 17 April 2020); original source: J. Jefferson Looney, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series, Vol. 8, 1 October 1814 to 31 August 1815 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 2011), 313–315. John Neilson was another Philadelphia joiner hired by Jefferson in 1803 to work on the remodeling of Monticello. The U.S. Capitol was being re-built following its burning by the British on 24 August 1814. Benjamin Henry Latrobe was the architect, with Munroe acting as superintendent of the construction. Dinsmore and Neilson, for whatever reasons, apparently never worked on the Capitol. For more information on James Dinsmore, John Neilson, and Jefferson’s other tradesmen, see K. Edward Lay, The Architecture of Jefferson Country: Charlottesville and Albemarle County, Virginia (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 2000).

[12] James A. Bear Jr., Jefferson at Monticello (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1967), 70.

[13] Bremo is acknowledged as one of America’s finest example of Palladian-style architecture.

[14] For more information on Monticello’s enslaved African Americans, including the remarkable Hemings family, see Lucia Stanton, “Those Who Labor for my Happiness”: Slavery at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press in Association with the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, 2012) and Annette Gordon-Reed, The Heminges of Monticello (New York: WW. Norton & Co., 2008).

[15] Thomas Jefferson, “Memorandums with respect to Watson,” 23 October 1793, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 27, edited by Julian P. Boyd, Charles T. Cullen, John Catanzarit, Barbara B. Oberg, et. al. (Princeton: Princeton University, 1950), 267. David Watson worked for Jefferson from June 1781 until March 1784 and again from March 1790 until February 1798. Of interest is a reference to a writing desk Watson was to make for Mary Jefferson Eppes (known as Polly as a child and Maria as an adult), one of Jefferson’s two daughters, in December 1793 (Ibid, 523). There are no other references to furniture made by Watson at Monticello; however, in 1786 he also worked for John Coles at “Enniscorthy” in southern Albemarle County, about fifteen miles south of Monticello, and is known to have made several pieces of furniture for Coles including a sideboard, bedstead, table, and numerous chairs. See Elizabeth Langhorne, K. Edward Lay, and William D. Rieley, A Virginia Family and Its Plantation Houses (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1987), 32–33. Although Watson worked at Monticello for eight years during his second period of employment by Jefferson, it is unknown how long Hemmings worked under him as there is only that single reference from 1793.

[16] “Dinsmore alone made and put up the semicircular arch of the Cabinet… in 10. days. Dinsmore and Johnny prepared & put up the oval arch in do. (8. feet wide in 12. days). … October 25. Tuesday. Dinsmore began to prepare some few things still unprepared in the Library. … Nov. 1. All the work being preparted he [b]egan to put it up, finishd. … Nov. 19. employed Dinsmore Nov. 1. 18. 19. otherwise Johnny Nov. 2. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. It took them 13. days work of Dinsmore 9. do. of John Hemmings.” Thomas Jefferson, September and October 1799, Farm Book Addenda, Coolidge Collection of Thomas Jefferson Manuscripts, Special Collections, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, MA (hereafter, Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS).

[17] Monticello: work memo, verso, 1804, Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS; available online: N147l; K149l [electronic edition], Thomas Jefferson Papers: An Electronic Archive, 2003, http://www.thomasjeffersonpapers.org/ (accessed 20 April 2020).

[18] Bear, Jefferson at Monticello, 101–102.

[19] A series of seventeen letters, thirteen authored by Hemmings and four by Jefferson, document much of Hemmings’s work at Poplar Forest between 20 October 1819 and 28 September 1825 (Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS).

[20] John Hemmings to Thomas Jefferson, 21 November 1821, Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS. For more information on John Hemmings’s architectural woodwork, in particular his work at Poplar Forest, see Emilie Johnson, “John Hemmings Enslaved Craftsman of Classical Architecture,” The Classiscist, No. 13 (2016): 8–15.

[21] In a letter to her son, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, Martha Jefferson Randolph wrote: “The elder girls have nothing but one of the bedsteads made by John Hemmings and your Aunt Randolph’s dressing table lent them by Burwell” (Martha Jefferson Randolph to Thomas Jefferson Randolph, 7 February 1830, Jefferson Family Papers, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA [hereafter, Jefferson Family Papers, UVA]).

[22] Thomas Jefferson to Edmund Bacon, 5 December 1811, in Looney, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: Retirement Series, Vol. 4: 306–307.

[23] Edwin Morris Betts, ed., Thomas Jefferson’s Farm Book (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1976), entry for 1 February 1818, p. 114. Lewis (1758–1822) was an enslaved carpenter and joiner who worked with hired joiners James Oldham, James Dinsmore, and John Neilson on the house. He worked laying floors, dressing plank, and fabricating exterior woodwork. Skilled with a lathe, Lewis turned balusters for the roof balustrade. After the house was completed in 1809, he worked with John Hemmings in the joiner’s shop. Lewis’s last name is unknown.

[24] Although several campeachy chairs associated with Jefferson are known, there is uncertainty about which, if any of them, were made by John Hemmings. For the evolving thinking on this complex subject, see Stein, The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson, 280–281; Self and Stein, “Collaboration of Jefferson and Hemings,” 243-244; Jack D. Holden, H. Perrot Bacot, Cybele T. Gontar, Furnishing Louisiana: Creole and Acadian Furniture, 1735–1835 (essay by Diane C. Ehrenpreis and Robert L. Self, “ ‘I Hope It May Answer Your Expectations’: Thomas Jefferson and the Campeachy Chair,”) 362–365; Diane C. Ehrenpreis, “The Seat of State: Thomas Jefferson and the Campeche Chair,” American Furniture 2010, Luke Beckerdite, ed., (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone Foundation, 2010); and Sumpter Priddy, “ ‘The one Mrs. Trist would chuse’: Thomas Jefferson, the Trist Family and the Monticello Campeachy Chair,” American Furniture 2012, Luke Beckerdite, ed., (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone Foundation, 2012).

[25] Ellen Wayles Coolidge Letterbook, 1856–1858, February 1856, Jefferson Family Papers, UVA.

[26] Joseph Coolidge Jr. was the son of Joseph Coolidge Sr., a prosperous Massachusetts merchant.

[27] Thomas Jefferson to Ellen Randolph Coolidge, 14 November 1825, in Edwin Morris Betts and James A. Bear Jr., eds., The Family Letters of Thomas Jefferson (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1966), 451; Interestingly, on 6 November 1822, Jefferson noted in his Memorandum Book: “Pd. Elijah Brown spectacles for J. Hemings 1.D.” Perhaps by 1826 Hemmings had either broken or lost his glasses, or his eyesight may have deterorated further to the point they were no longer effective.

[28] Ellen was writing to Jefferson’s early biographer, Henry Randall. Ellen Wayles Coolidge Letterbook, 1856–1858, Jefferson Family Papers, UVA.

[29] Cornelia Jefferson Randolph to Virginia Jefferson Trist, 22 August 1831, Nicholas Philip Trist Papers #2104, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. John and Priscilla Hemmings were affectionately referred to by the family as “daddy” and “mammy.”

[30] According to Lynn Rainville’s study of African American graveyards in central Virginia: “In my research of three dozen antebellum cemeteries, which include 406 individual slave gravestones, I’ve found less than five percent of the markers to be inscribed.” Lynn Rainville, Hidden History: African American Cemeteries in Central Virginia (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia, 2014), 2.

[31] Various scholars, including Lucia Stanton, Shannon Senior Historian, Monticello (retired) and Lynn Rainville (see Endnote 30), have been unable to reach a conclusion regarding the word “sed.” Hemmings may have learned about stone carving from Thrimston Hern, who was also enslaved at Monticello. Hern, although a much younger man (b. 1799) than Hemmings, was assigned to work with the Lynchburg, Virginia stonecutter John Gorman at Monticello for several years. In 1823 they cut and installed slated paving of Monticello’s east and west porticoes and carved and installed the caps and bases for the West Portico columns. According to Gorman, he trained Hern into a “tollerable good stone cutter.” Following Jefferson’s death, Hern was purchased by University of Virginia Proctor Arthur Spicer Brockenbrough and worked at the university completing the stonework of the Rotunda. See Stanton, “Those Who Labor for my Happiness,” 140.

[32] The only known graveyard for enslaved African Americans at Monticello is located just southwest of the Visitor Center. Between forty and a hundred graves of unidentified individuals are laid out in north-south rows with burials oriented east-west. Many graves were marked at the head and sometimes foot with uninscribed fieldstones; wood markers might also have been used. A sensitive archaeological investigation of this site is pending.

[33] A search of the detailed packing lists for items shipped from various locations did not reveal any evidence for a separate tabletop. Nor is there any evidence that the top itself was re-used from another table.

[34] James Oldham (d. 1843) was a house joiner hired from Philadelphia in 1801 to work on the exterior joinery of Monticello. In the fall of 1804, he moved to Richmond to set up his own joinery shop. Oldham continued his relationship with Jefferson, making nearly all of the doors for the house as well as the window sashes for the South Piazza (Greenhouse). He also procured mahogany for Jefferson on at least two occasions. He later returned to Albemarle County and worked on the construction of the University of Virginia.

[35] Thomas Jefferson to James Oldham, 12 October 1807, Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS.

[36] James Dinsmore to Thomas Jefferson, 11 December 1807, Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS.

[37] Thomas Jefferson to James Dinsmore, 15 December 1807, Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS.

[38] Thomas Jefferson to James Oldham, 15 December 1807, Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS. Jefferson also knew exactly what he wanted for the sash stock; it should “of course” be “strait grained” and of a specific length to allow for efficient cutting of the sash bars. Travis McDonald, Director of Architectural Restoration for Jefferson’s Poplar Forest, notes “Jefferson learned, as had Palladio before him, that architects can’t just learn the lessons of design; they must also study how buildings are actually constructed.” Thus Jefferson knew, that in order to be stable and resist warping, sash stock must be straight grained, something “of course” Oldham would have also understood as a joiner. See Travis McDonald, “Tom the Builder,” UVA Magazine, Spring 2018.

[39] James Oldham to Thomas Jefferson, 24 December 1807, Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS.

[40] Santo Domingo mahogany (Swietenia mahogoni) is a dark, dense mahogany indigenous to the Greater Antilles in the West Indies. This species is referred to variously as Santo Domingo mahogany, Cuban mahogany, Jamaican mahogany, etc. depending on which particular island produced it. Each apparently had slightly different qualities, in the same way that Virginian walnut, for instance, varies from that grown in Pennsylvania owing to subtle differences in soil and climate. Also referred to as simply “Spanish wood” or simply “island mahogany,” Santo Domingo mahogany’s better-known cousin, Honduras mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla,), also called “Bay wood” in the period, is the species chosen by Oldham for the window sash stock. Perhaps owing to its being more readily available, the Honduras mahogany sent by Oldham cost one third less than the Santo Domingo. Although costing the same per running foot, the Honduras timbers are one and one-half inches thick versus one inch for the Santo Domingo lumber. Thomas Sheraton describes both species in The Cabinet Dictionary (1803): “Hispaniola or St. Domingo, is a West Indian Island and produces dying woods and mahogany of a hardish texture…”; and, echoing Oldham’s comment, “it is not much in use here.” Sheraton’s description of Cuban mahogany, which is very similar to Santo Domingo, gives us a fuller picture of the character of these “island” mahoganies: “Cuba wood is a kind of mahogany somewhat harder than Honduras wood, but of no figure in the grain… . It is generally used for chair wood, for which some of it will do very well.” Honduras mahogany, on the other hand, is described as: “…the principal kind of mahogany in use amongst cabinetmakers…having a very different quality [than Santo Domingo mahogany] and frequently of a more flashy figure.” So whether Oldham correctly interpreted the meaning of “fine mahogany” depends on if Jefferson wanted the dense, rich quality of Santo Domingo mahogany or if he would have preferred the “flashy” character of Honduras. Other than a cursory note from Jefferson thanking Oldham for obtaining the mahogany for him, there is nothing to tell us one way or the other.

[41] Thomas Jefferson to James Dinsmore, memo, 3 January 1808, Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS.

[42] James A. Bear Jr., ed., “Directions for Mr. Bacon June 7, 1808,” Jefferson at Monticello: Recollections of a Monticello Slave and of a Monticello Overseer (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1967), 67–68 (originally published by Hamilton W. Pierson, Jefferson at Monticello: The Private Life of Thomas Jefferson [New York: Scribner, 1862], 65–67). Goods were frequently transported both up and down the James River, as well as other navigable rivers, in flat-bottomed boats called “batteaux” (the singular is “batteau”). For fragile items (such as freshly glazed window sashes) this was especially preferred to overland transport. Writing to his daughter Martha concerning the shipment to Monticello of delicate furnishings, part of a large lot that had previously been circuitously sent from France to Philadelphia and thence to Richmond, Jefferson said, “I enclose you the list wherein I have marked with an * the boxes which must remain in Richmond till they can be carried by water, as to put them into a wagon would be certain to sacrifice them.” Items marked included terra cotta busts, glassware, marble tops for commodes, and looking glasses. Thomas Jefferson to Martha Jefferson Randolph, 12 May 1793, John Catanzariti, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson (Princeton, NJ, Princeton University, 1995), 26:18.

[43] James Dinsmore to Thomas Jefferson, 24 June 1808, Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS. Without having to worry about the sashes, Dinsmore decided, perhaps because of the tremendous weight of the stoves, sash weights, etc., the cargo would be more easily (“best”) transported overland rather than laboriously poling it upriver to Lynchburg in a batteau.

[44] Edmund Bacon to Thomas Jefferson, 30 June 1808, Jefferson Family Papers, UVA. The date 30 June in 1808 was a Thursday; the previous Saturday, then, would have been 25 June, so the wagon left the day after Dinsmore packed it up on the 24th. The reader may note that only nine letters were cited rather than eleven as stated. One additional letter was written requesting mahogany from another source (Thomas Jefferson to George Jefferson, 15 December 1808, Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS). This letter simply repeated the same information contained in Jefferson’s initial letter to Oldham. The second additional letter was a brief note to Oldham thanking him for procuring the mahogany (Thomas Jefferson to James Oldham, 7 February 1808, Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS).

[45] S. Allen Chambers Jr., un-published research compilation of letters associated with Poplar Forest, March 1989, Poplar Forest Archives, Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest, Forest, VA.

[46] Hugh Chisholm to Thomas Jefferson, 22 July 1808, Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS.

[47] Thomas Jefferson to Hugh Chisholm, 8 September 1808, Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS.

[48] James A. Bear Jr. and Lucia C. Stanton, eds., “Chronology,” Jefferson’s Memorandum Books: Accounts, with Legal Records and Miscellany, 1767–1826, two vols. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 1997), vol. 1, liii. A subsequent letter from Dinsmore to Jefferson indicates the sashes were completed sometime around mid-July 1808: “The wagon was obliged to leave the sash weights behind being overloaded so that we must send them and the cord along with the sashes, which will be ready in a fortnight… .” James Dinsmore to Thomas Jefferson, 1 July 1808, Jefferson Manuscripts, MHS.