The recent sale of a circa 1790 Charleston secretary wardrobe featuring a signature that appears to read “John Gough” has increased awareness of the free African American cabinetmaker of the same name. The mahogany secretary wardrobe (Figure 1) along with a previously overlooked primary resource significantly add to our understanding of this craftsman, including how he attained his freedom, under whom he may have trained as a cabinetmaker, and the possible identity of his parents. These two documents—one physical and the other archival—are exceedingly rare survivals for an eighteenth-century free person of color, especially a skilled craftsperson. Through thoughtful analysis and consideration of historical documents and the secretary bookcase we can add substantially to what is known of the life and career of John Gough.

In 1790, besides the communities of at least nine separate European groups, the South Carolina coastal region included some 51,000 enslaved Africans by 1790, many of whom were held in the greater Charleston area. In addition, the city of Charleston was home to nearly six hundred free African Americans, about a third of the total number of free Black individuals in all of South Carolina (Figure 2).[1] Free Black craftspeople were likely drawn to Charleston by the security offered by the city’s sizeable community of free African Americans as well as the potential for profitable business ventures.[2] Enslaved craftspeople, too, could capitalize on their individual skills. Charleston’s slave hire system, in place by late eighteenth century and formalized in the nineteenth century, profited slaveowners through the work of enslaved artisans and laborers but in some cases also provided opportunities for enslaved workers to earn income of their own.

Of the two-dozen African American artisans identified by the MESDA Craftsman Database in South Carolina in 1790, more than half were recorded as working in Charleston.[3] Also, it is vital to note that, besides these known men, it remains nearly impossible to quantify the number of enslaved, unrepresented and unnamed, working within Charleston’s trade shops within the last quarter of the eighteenth century.

An ability to successfully participate in the city’s building trades seems to have been an enticement for South Carolina’s free Black craftsmen of the eighteenth century. In her article “South Carolina’s Forgotten Craftsmen,” Allison Carll-White identified a dozen free African American craftsmen working in the city from 1760 to 1800.[4] Nearly every man she recorded was a carpenter or bricklayer. Some also completed the work of a joiner.[5] Only one was listed as a cabinetmaker. His name was John Gough.

The first decorative arts scholar to identify John Gough as a cabinetmaker was E. Milby Burton in his seminal 1955 book Charleston Furniture, 1700–1825.[6] Although Burton did not establish Gough’s status as a freedman or his race—Allison Carl White’s 1985 article was the first to do that—Burton’s two-sentence entry for Gough provided the name of a cabinetmaker for Brad Rauschenberg and John Bivins to pursue in their exhaustive research that culminated in the 2003 book The Furniture of Charleston, 1680–1820.[7]

The meticulous biographical entry that Rauschenberg and Bivins assembled for Gough provides the most complete biography of the cabinetmaker to date. They established that Gough was a free Black cabinetmaker working in Charleston from 1766 to about 1800. The records revealed that Gough and his wife Margaret Cordes Gough were heavily involved in real estate and that the couple enslaved a number of individuals between the years 1774 and 1791.[8]

Despite these important additions to Gough’s biography, there were questions that remained unanswered. Among the unknowns were whether John Gough was born free or enslaved, who his parents were, and if there is any surviving furniture made by his hand. This article attempts to answer those questions through previously unexamined documents and the recent sale of a significant late eighteenth-century Charleston secretary wardrobe.

1763: Freedom Priced and Purchased

The crucial document for expanding our understanding about John Gough’s life is the 1763 will and testament of Elizabeth Akin.[9] Unknown to previous furniture scholars, Akin’s will reveals that the cabinetmaker John Gough was born enslaved. Furthermore, the document, which was written on 23 February 1763 and proved on 23 September of the same year, set forth the terms through which Akin’s estate would provide Gough his freedom.[10]

Elizabeth Akin was only about twenty years old when she died. She never married and did not appear to have any surviving family. Both her parents had died in the 1750s.[11] Also, it is doubtful that Gough was residing in Charleston with her when she died, as she was living with the Harleston family.[12] It is possible that Gough may not have even worked and lived in the city while he was enslaved and during the first years of his freedom because he was recorded into the early 1770s as “of Christ Church Parish” (located across the Cooper River from Charleston) (Figure 3).[13] These records most often referred to Gough as a “freed negro,” but later newspaper notices described Gough as mixed race or, more specifically, “mulatto,” as Akin did in her 1763 will.[14]

Like many slaveholders who manumitted individuals they enslaved, Elizabeth Akin required that monetary payment be made by Gough in return for his freedom.[15] In particular, Akin required Gough to pay £250 to one of her executors before he was released from bondage. Interestingly, however, despite the required amount paid by Gough for his freedom, the will included an additional clause mandating a sort of refund as it were, of monetary resources that would ensure Gough’s ability to provide for himself as a newly freed man: “I do direct that they pay him when his is Freed the Sum of Fifty pounds Current Money to Enable him to purchase Tools that he may get his Livelyhood by his Trade.”[16]

Although Gough’s trade is not specified in Akin’s will, her attempt to ensure that Gough had the means to purchase tools suggests a trade such as a cabinetmaker, which, like that of a silversmith, was considered among the top-tier occupations within the craftsmen population of Charleston. Their level of talent required significant investments in quality tools, each one crucial to their ability to find suitable work. Based on Akin’s choice of words it seems certain that Gough was already trained in his trade and had been working for some time under an agreement with Akin, whether hired out to another craftsman or finding his own work and paying some or all of his profits to Akin.

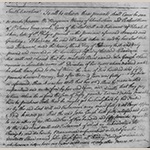

Further indication that Gough was already skilled and working at his trade when Akin died is the fact that he required only two months to raise the £250 needed to purchase his freedom. Indeed, this is a rather astounding feat for his time, one that perhaps points to his well-established personal or commercial relationships (or both) in the city. Whatever the case, Benjamin Waring submitted to the court on 21 November 1763 (Figure 4):

Now know ye, that the said John Gough hath fully satisfied and paid to us or either of us, the said Sum of Two hundred and fifty pounds, agreeable to the said Last will and Testament which we acknowledge the receipt, and do hereby Manumize enfranchise and set free the said Mulatto Slave named John Gough from all Slavery Bondage or Servitude whatsoever… .”[17]

A little over two years after his emancipation, on 6 January 1766, Gough married Margaret Cordes, a union that proved to be invaluable when attempting to reveal how the pair may have met, from whom he received his cabinetmaking training and, potentially, his heretofore unknown parentage.

1766–1770: Marriage Reveals Cabinetmaking Training and Parentage

Margaret Cordes was the daughter of a freedman named Charles Cordes, who died in 1770, four years after his daughter’s marriage to Gough.[18] John Gough was named executor of his father-in-law’s estate. Although these records do not reveal Charles Cordes’s occupation, when the available evidence is evaluated there is reasonable likelihood that John Gough trained as a cabinetmaker under the tutelage of Charles Cordes.

Charles Cordes was born enslaved, probably in St. Johns, Berkeley Parish (see Fig. 3), and given the name Plymouth. His enslavers were members of the Cordes family, a successful and extensive family of French Huguenot planters in St. Johns, Berkeley Parish. Plymouth was the first enslaved person recorded in the 1745 probate inventory of Isaac Cordes (Figure 5).[19] Of particular note is that Plymouth was valued at £400, nearly twice that of any of the other 114 people enslaved on Cordes’s plantation. This appraisal clearly indicates that Plymouth was a worker who possessed a valuable set of skills—possibly those of a cabinetmaker or house joiner. Plymouth was manumitted in 1749 by Isaac Cordes’s daughter, Hester Cordes Dwight.[20] Like Gough’s 1763 emancipation, this event was not purely altruistic as she required Plymouth, recorded as living in Christ Church Parish at the time, to pay her the substantial sum of £750 for his freedom.[21] That same year Plymouth changed his name to Charles Cordes and was baptized at St. Philips Church in Charleston.[22]

Though it’s certainly possible that Cordes may have been hired to a Charleston cabinetmaker prior to his owner’s death in 1745, he was working in or just outside of Charleston by 1749 at the time of his baptism. This puts him in the right place at the right time with the right skills to have trained John Gough as cabinetmaker. Cordes could have begun training John Gough as a cabinetmaker in the late 1750s, when Gough was almost certainly in Charleston and enslaved by Elizabeth Akin. Additionally, both men were recorded living in Christ Church Parish in the 1760s. Finally, and after Gough purchased his freedom, his relationship with Cordes deepened. Gough married Cordes’s daughter in 1766. And in 1770 he was named the administrator of his estate upon his death in 1770.

The Cordes, Gough, and Akin families appear throughout the records of St. Johns, Berkeley Parish in the eighteenth century.[23] These surnames also appear in the probate records of a wealthy St. Johns, Berkeley planter named Richard Gough (d. 1753).[24] Richard Gough’s plantation abutted land owned by the Cordeses and there are numerous notations of bonds and sales between the two families. Of particular note, in Richard Gough’s 1753 estate inventory there is listed among the seventy-four enslaved people a “Jane and Child Johnny” valued at £420 (Figure 6).[25]

While difficult to determine with any certainty, the possibility exists that the freedman cabinetmaker John Gough was the son (“Johnny”) of Jane and her enslaver Richard Gough. As previously mentioned, the cabinetmaker John Gough was referred to as “mulatto” in Elizabeth Akin’s will and was consistently and regularly described the same way in newspaper notices. The Huguenot families of St. Johns, Berkeley Parish were deeply intertwined through marriage, land, and commerce. Those they enslaved were as well. Further research may explain exactly how an enslaved man with the surname Gough, a man who later married a woman who was the daughter of a man enslaved by the Cordes family, came to be owned and freed by Elizabeth Akin.

1770–1790: Land Speculation and Slave Ownership

The biography that Brad Rauschenberg and John Bivins published in their 2003 book remains a thorough and accurate account of Gough’s life during the 1770s and 1780s. After 1770 the historic record reflects a man who was striving for respectability in his community, yet at the same time these records also reveal someone possessing some questionable character traits. What may seem contradictory at first may in fact simply signify the precariousness that all free African Americans experienced in late eighteenth-century Charleston, and in America as a whole. Caught between slavery and white society, free Black Charlestonians in some ways could attain levels of respectability and economic success that were on par with some of their white contemporaries but at the same time remained vulnerable to abuse and exploitation by that very same white society.

In 1772 Gough seems to have achieved some acceptance into white society, at least in name, for he was recorded as a “planter of Christ Church” when he purchased land in Charleston’s Colleton Square for £3,000.[26] Gough and his wife would buy and sell land in Charleston throughout the 1770s and into the 1780s. Margaret seems to have been an active partner in the couple’s land speculation. For example, in December 1770 she was given part of a Charleston town lot.[27] And in March 1777, Margaret and John, recorded as “cabinetmaker of Charleston,” sold land in Colleton Square for £1,200.[28]

Still, despite these perceived successes, the precariousness of the Gough’s legal standing as free Blacks in Charleston can be seen in an 8 March 1783 newspaper announcement in response to some of the couple’s land transactions and their clear titles to them:

PUBLIC Notice is hereby given for all Persons to be careful of purchasing lands and temements of a certain free Mulatto Man named JOHN GOUHH [sic], a Cabinet maker, particulary that House and Lot, No. 14, in Guignard‑street, and the vacant Lot thereto adjoining, the same being under a Lease of Twenty‑one Years, &c. For Information, enquire of EMANUEL ABRAHAMS, No. 50, King‑street.[29]

A year later, on 6 April 1784, it appears the property’s ownership was still in question. Gough asserted that he owned “a lot of Land, fronting Guignard-street” that he wished to sell but another free African American, John Lamputt, also claimed the property.[30]

In addition to land speculation, John Gough was also an active participant in the trade of enslaving other African Americans, although whether any of these men or women were incorporated within his cabinetmaking business is unknown. In May 1774, he mortgaged a woman named Cloe to coachmaker Matthias Hutchinson in order to satisfy a bond of £1,000.[31] Two years later, in 1776, a notice was published in which John Valk announced the self-emancipation of possibly the same woman named Cloe, who was “once the property of John Gough, cabinetmaker in Charleston.”[32] And on 5 July 1790, Gough mortgaged two enslaved men, Martin and Jack, and a schooner named “Friendship” to William McKimmy for £261.[33]

1785–1795: The Secretary Wardrobe

In 2019 a Charleston-made secretary wardrobe (Fig. 1) came to market featuring what appeared to be the signature of John Gough.[34] Located on the top of the bottom case, the white chalk signature has worn away in places but is clearly readable, with a second “John” visible below and to the right of the full name (Figure 7).[35] The combination of a significant example of case furniture displaying regional characteristics along with the signature of a known eighteenth-century African American cabinetmaker in that region captured the interest of numerous curators and collectors across the country. The Historic Charleston Foundation ultimately purchased the secretary wardrobe to exhibit at the Nathaniel Russell House on Meeting Street.

The attention given to this secretary wardrobe (or linen press) was merited.[36] Surviving furniture with the signature of its likely maker is rare. Surviving signed furniture attributable to an enslaved or free Black cabinetmaker is virtually unheard of. Notable exceptions include the work of North Carolina’s Thomas Day (Figure 8) and John Hemmings (Figure 9) at Monticello’s Joinery.[37] Day and Hemmings are two of only seventy-three southern African American cabinetmakers, free and enslaved, recorded by the MESDA Craftsman Database.[38] The extant furniture attributed to them—Thomas Day excluded—can be counted on one hand. And all were made in the nineteenth century.

One of the handful of other known examples is a circa 1810 desk made in Edenton, North Carolina with the name “Burke” written on the bottom of a drawer (Figure 10).[39] Timothy Burke was recorded by John Bivins as a free Black cabinetmaker’s apprentice under Thomas Hankins and his partner William Manning beginning in 1803 and 1807, respectively. Bivins also made note of a sideboard with the pencil inscription “Timothy Burke / Cabinetmaker / Edenton,” evidence that Burke worked on his own after completing his apprenticeship.[40]

Another notable survival of furniture by an African American cabinetmaker is a chest of drawers at the Charleston Museum (Figure 11). The piece itself is consistent in fit and finish to several others attributable to the shop of Scottish-born Robert Walker, a prolific Charleston cabinetmaker working between 1795 and 1833. Like other Charleston cabinetmakers including Jacob Sass and William Axson, Walker was known to sign or mark his shop’s completed works, certainly a more permanent branding than traditional paper labels typical of the period (although Walker employed paper labels as well). Both signatures and labels, however, were usually administered in concealed-yet-easily-accessible locations such as a drawer bottoms. This chest of drawers, however, features a not-so-easily-found penciled signature and date under the top board: “Boston, October the 18th, 1805” (Figure 12). The name Boston appears without surname in the 1790 census, followed by the single word “free” in parenthesis. No other individual named Boston can be found until Katherine Boston, also a free person of color, appears in the 1822 Charleston city directory.[41] Thus, it’s possible that an African American freedman named Boston worked under Walker as a possible joiner at least during the autumn of 1805. The marking’s placement also adds to Boston’s mystery as the top board, once signed, was covered by the chest’s top and almost permanently concealed from view until recent repair work revealed it.[42]

Stylistically, the “John Gough” secretary wardrobe fits firmly into Charleston’s late eighteenth century furniture vocabulary, reflecting the city’s cabinetmaking traditions from the 1770s and 1780s while at the same time embracing fashionable neoclassical influences that wouldn’t fully bloom until after the turn of the nineteenth century. Wardrobes—and their more expensive siblings which included a secretary drawer—were a popular form of furniture made in many of Charleston’s cabinetmaking shops. They are often associated with German-speaking craftsmen such as Jacob Sass, Henry Gesken, and Charles Desel.[43] Further evaluation, however, points to construction features that place the Gough example within a shop that was influenced by the city’s German School furniture but equally, if not more so, by the New England furniture coming to Charleston via the venture furniture trade and the skills of migrating cabinetmakers.[44]

The use of cypress as one of the secondary woods (Figure 13), as well as the inclusion of central muntins on the bottoms of the large drawers of the lower case (Figure 14), establish the secretary wardrobe’s Charleston origins. Its other secondary woods include red cedar, white pine, and yellow pine, all commonly found on the city’s late eighteenth century furniture. The secretary wardrobe deviates from the work of Charleston’s Post-Revolution German School shops in the more circular (rather than oval) sweep of its scrolled pediment (Figure 15), its lack of graduated drawers on the lower case (Fig. 1), door frames that are butt joined (not mitred) at the corners and not covered with veneer (Fig. 15)—all features that reflect British and New England influences on Charleston’s furniture of the late eighteenth century.

Also exhibiting the influence of both the German School shops and British/New England craftsmanship is a library bookcase now on exhibit at the South Carolina Governor’s Mansion (Figure 16).[45] The library bookcase possesses several features reproduced on the secretary wardrobe, although with a bit less sophistication, pointing to a locally trained craftsman mimicking the work of someone else.[46] For example, the pomegranate rosettes found on the secretary wardrobe, although replaced, were carved based on surviving material evidence to reflect those found on the library bookcase (Figures 17 and 18). More importantly, the pediment geometry of the library bookcase follows that of the German School shops while the secretary wardrobe incorporates the more circular plan that reveals the influence of furniture imported from Salem, Massachusetts, and sold locally in Charleston.

In addition to the German and New England influences found on the secretary wardrobe, the layout of its bottom case drawers hints at the coming flood of British—more specifically Scottish—cabinetmakers who would arrive on Charleston’s shores in the late 1790s and early 1800s. This immigration would, alas, quickly push conservatively decorated and standardly styled pieces like the Gough secretary wardrobe out of style by the turn of the nineteenth century. It is one of only a handful of known late eighteenth-century Charleston secretary wardrobes that does not feature inlay and hardware on the face of its secretary drawer to create the illusion of two half-width drawers (Fig. 1). In addition, of the thirty-eight Charleston wardrobes recorded by the MESDA Object Database, only one example (Figure 19) carries this same full-width top-drawer style on its lower case.[47] That wardrobe, made in the late 1780s and now in a private collection, provided the basis for Rauschenberg and Bivins to introduce their discussion about the influx of Scots into the Charleston market:

A sizeable percentage of the case furniture illustrated below is associated with English and New York styles brought to Charleston by Scottish cabinetmakers. The clothes press, or wardrobe, as it was variously known, was a pervasive form in Charleston. They are relatively generic in form, following the appearance of the usual run of good quality but conservative British work. In comparison with other Charleston wardrobes, however, the piece shown in figure NC-53 [Fig. 19] rises above the boredom of homogeneity by virtue of its astragal-molded, flush-paneled doors and the finish of its bracket feet.[48]

Taken in total, it can be deduced that John Gough most likely contributed to the production of this particular secretary wardrobe sometime between 1785 and 1795 and was hired as a journeyman in a Charleston cabinetmaking shop operated by a recent Scottish arrival, perhaps via New York or New England, who may have had some connection to the city’s German community. One candidate that leaps forward is John Watson.[49]

Born circa 1751 in Musselburgh, located about five miles east of Edinburgh on the coast of Firth of Forth (Figure 20), John Watson arrived in Charleston about 1785, possibly to join his brother George, an upholsterer.[50] John would have arrived about thirty-five years of age and fully trained in the “art and mystery” of cabinetmaking. The Watson brothers worked in partnership until George’s death in 1791.

Of particular note, not long after arriving in Charleston John Watson signed the rules and orders of St. John’s Lutheran Church.[51] His choice of congregation may be curious, as most consider Scotland a Presbyterian country, and Watson would eventually be buried in the Anglican churchyard of St. Michael’s.[52] Regardless, St. John’s Lutheran was the church of cabinetmakers Jacob Sass, Henry Gesken, and Charles Desel, with Sass serving as president of the vestry for nearly twenty years.[53] Thus a recent Scottish emigree was weekly worshipping at the epicenter of the city’s German-speaking cabinetmaking community.

1790 found John Watson’s shop at 21 Tradd Street. That same year the first United States Census recorded Watson as the head of a household that included a white male under the age of sixteen, three white women, and one enslaved person. After the 1791 death of George Watson—with Jacob Sass serving as an appraiser of George’s estate—and the subsequent dissolution of their partnership, John Watson embarked upon a twenty-one-year span as a successful cabinetmaker in Charleston. In 1796 he advertised “Secretary and Wardrobe, Wardrobes and Secretaries” and took on a female apprentice, Mary Bowden, to learn the skills of an upholsterer. A year later he placed a notice that stated: “He flatters himself his workmanship will bear the strictest examination, and will be equal to any imported, as it has been his study to procure the best Workmen, both from London and Paris.”[54]

It may not be possible to ascertain whether or not John Gough was one of the “best Workmen” procured by John Watson. It is also impossible to determine with certainty if the secretary bookcase was indeed a product of Watson’s shop. What is known for certain is that Watson was one of only a very few cabinetmakers working in Charleston between 1785 and 1795 who was trained as a cabinetmaker in Scotland, had the means to operate his own shop, and had undeniable ties to the city’s German School cabinetmakers. He also clearly reflects the far-reaching and cosmopolitan nature of Charleston’s cabinetmaking trade in which Lowcountry-born furnituremakers worked alongside German-speaking Lutherans, New England Yankees, recent Scottish immigrants, and African Americans, both free and enslaved.

Perhaps it is with more than a little bit of satisfaction that we can include the name of one of those skilled African Americans in Watson’s shop. After his death in 1812, a newspaper advertisement by auctioneers Campbell & Milliken revealed that among those “best Workmen” in Watson’s shop was an enslaved furnituremaker named David:

…will be sold before our vendue store, on TUESDAY, the 23rd of February, A NEGRO FELLOW, named David, a Cabinet Maker by Trade, belonging to the Estate of John Watson, late of Charleston, deceased.[55]

Nothing more is known about David the cabinetmaker.[56]

1790: Brown Fellowship Society, Jail, Death?

As the last decade of the eighteenth century began, John Gough and his wife Margaret were continuing to purchase and sell land as well as people.[57] The latter activity, slaveholding, did not exclude Gough from becoming the first person to apply and be admitted to Charleston’s Brown Fellowship Society, a benevolent organization for Charleston’s free African Americans established in November 1790.[58]

A significant example of how racism affected the African American community itself, Charleston’s Brown Fellowship Society was founded by men of mixed racial identity to promote and support their positions in relation to white society. Indeed, the society did nothing to assist enslaved African Americans and many members were slaveholders themselves.[59] John Gough met all of those criteria.

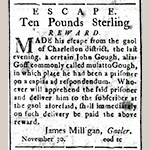

The very same month that Gough was admitted to the Brown Fellowship Society he also found himself under arrest by James Milligan, the Charleston District jailer.[60] Strikingly, the only document giving details of his detainment is a newspaper posting alerting the Charleston community of his escape from the jail (Figure 21). The reason for his arrest is unknown other than that he was facing a civil charge of some kind (“capias ad respondendum”). Whatever the charge’s severity, the fact that Gough risked escape from it reveals his inner intuitions that as a man of mixed race, despite his accomplishments, status, and relative wealth, he was unlikely to receive the fair trial and treatment expected by a free white craftsman in the same situation. Milligan offered a £10 sterling reward for Gough’s capture.[61]

The events of November 1790 place the polarities of John Gough’s life into sharp focus. Gough was a free African American craftsman and landowner, a prominent member of the free Black community, and a charter member of the Brown Fellowship Society. Gough was also accused of benefitting from the lease or sale of property that was not his, he enslaved individuals for his own profit, and was arrested and jailed for unknown reasons. While the events and traits that surround him may seem to be in stark contrast to many of us today, in fact they help to illustrate the fragile and certainly precarious status of a freedman living and working in a white world. Such duality, confusing as it is, may have been perceived as commonplace in Charleston at the time.

There are only two possible paths for John Gough after that momentous month of November 1790: He either died—or was killed, possibly while attempting escape from jail or while in custody—or he did in fact escape his captors and left Charleston for good. Not a single document has been found to prove Gough was alive after November 1790, either in Charleston or elsewhere. His appearances in the historic record after the sheriff’s notice of his escape are limited to the sale of his land and property, including an enslaved woman named Charlotte “Late the Property of John Gough alias John Goff.”[62] Consequentially, Gough’s disappearance also provides a firm 1790 cut-off date for the manufacture of the secretary wardrobe bearing his name.

He was certainly considered deceased by 1811, when Margaret Cordes Gough, “widow of John Gough, late of Charleston,” released her dower that was a claim to part of a lot on Unity Alley.[63] Margaret herself died sometime after 1814, when she too disappeared from the Charleston records.[64]

Conclusion

Renewed scholarship stemming from Historic Charleston Foundation’s 2019 acquisition of the circa 1790 secretary wardrobe featuring the signature of John Gough has dramatically enhanced our understanding of a free Black cabinetmaker working and living in late eighteenth-century Charleston. Specifically, revisiting the historic record brought the will of Elizabeth Akin to the attention of furniture historians for the first time. As a result, details of John Gough’s enslavement and emancipation have been revealed, and possible answers have been put forward for questions about Gough’s parentage and training as a cabinetmaker.

Evaluating the secretary wardrobe within the stylistic and social context of late eighteenth-century Charleston highlighted the complex, cosmopolitan influences on the city’s large urban cabinetmaking shops. Culturally, the furniture made in Charleston in the late 1780s into the 1790s—including the secretary wardrobe—amply reflects the hands of German, Scottish, New England, African American, as well as local Carolina cabinetmakers. The secretary wardrobe also provided a trail of research that reached beyond John Gough’s story to include David, a heretofore unnamed and unrepresented cabinetmaker enslaved by John Watson in the first decade of the nineteenth century.

The evolving biography of John Gough poignantly demonstrates the duality of existence that a free Black craftsman experienced in Charleston at the close of the eighteenth century. It is hoped that the search for more information about John Gough’s life will be continued by emerging historians of material culture, especially those focused on African American craftspeople.[65] Whether to confirm or invalidate the suppositions put forward in this work, the authors encourage continued and deeper study into the life and work of the enigmatic cabinetmaker John Gough.

Grahame Long is the Director of Museums at Historic Charleston Foundation. He is the author of several books on Charleston’s social and material history, including Lost Charleston, an exploration of the city’s lost architectural treasures. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Gary Albert is the Director of MESDA Research at Old Salem Museums & Gardens. He is the editor of the MESDA Journal and also serves as the museum’s adjunct curator of silver and metals. He can be reached at [email protected].

[1] There were 1,801 free African Americans in South Carolina; 950 (53 percent) lived in the Charleston District and 586 (33 percent) lived in the city of Charleston. 1790 Census: Whole Number of Persons within the Districts of the U.S., Data Tables, p. 54, United States Census Bureau, Washington, DC: online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1793/dec/number-of-persons.html (accessed 8 August 2020); Ibid. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1790/number_of_persons/1790a-02.pdf (accessed 19 October 2020).

[2] For example, The Brown Fellowship Society, an organization founded in 1790 specifically for Charleston’s free blacks (and one in which John Gough affiliated), provided its members a certain level of financial aid “for times of illness and indigence,” and further provided suitable funerary arrangements if necessary. The Society restricted its membership to fifty men and required a $50 initiation fee followed by regular monthly dues. Junius P. Rodriguez, Slavery in the United States, Vol. 1 (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2007), 203.

[3] The MESDA Craftsman Database records twenty-three enslaved artisans in South Carolina in 1790; twelve (52 percent) were identified in the Charleston District (all in the city of Charleston) . In the same year, three free African American artisans were recorded in South Carolina, all working in the city of Charleston. MESDA Craftsman Database, online: https://www.mesda.org/craftsman-database (accessed 8 August 2020).

[4] Allison Carll-White, “South Carolina’s Forgotten Craftsmen,” South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 86, No. 1 (January 1986): 32–38.

[5] One of those men was John “Quash” Williams, the subject of Dr. Tiffany Momon’s excellent study presented in this 2020 issue of the MESDA Journal.

[6] E. Milby Burton, Charleston Furniture, 1700–1820 (Charleston, SC: The Charleston Museum, 1955), 93.

[7] Bradford L. Rauschenberg and John Bivins Jr., The Furniture of Charleston, 1680–1820, three volumes (Winston-Salem, NC: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 2003), Vol. III, 1031–1033.

[8] Perhaps as importantly, Rauschenberg and Bivins were able to begin to differentiate records for at least two men named John Gough living in Charleston in the second half of the eighteenth century: one the free African American cabinetmaker and another a white man who married a woman named Rebecca Hext in 1776. Rauschenberg and Bivins, Vol. III, 1032.

[9] Charleston County Will Book, 1767–1771, Vol. 11, pp. 105–107, Civil Works Administration Transcripts, microfilm, Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939L-JXSZ-G8?i=119&wc=M6N4-F6D%3A210905601%2C211576301&cc=1919417 (accessed 8 August 2020). See also Carll-White, “South Carolina’s Forgotten Craftsmen,” 37, note 23.

[10] Elizabeth Akin’s will is a fertile document for research by a social historian, especially someone looking into gender and enslavement. For instance, in addition to John Gough she also manumitted a man named Thomas and his wife Mary. Of particular note is that Akin gave all of her clothing to Mary, not a white friend or family member.

[11] An exact birth date in not known for Elizabeth Akin, Her parents, James Akin and Sarah Bremar, were married in 1741 and Sarah died in 1750. Thus Elizabeth would have been born sometime in the 1740s.

[12] For Elizabeth Akin’s residence with the Harleston family, see Dr. Nic Butler, “The Forgotten Akin Family of Charleston,” Charleston County Public Library blog, 12 October 2018, online: https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/forgotten-akin-family-charleston (accessed 8 August 2020).

[13] For example, see Elizabeth H. Jervey, “Abstracts of Records of the Proceedings in the Court of Ordinary, 1764–1771” SCHGM 43 [1942]: 248; Charleston County Court of Common Pleas, Renunciation of Dower, 1740-1787, 1767–1772, p. 129, 18 September 1770, microfilm, South Carolina Department of Archives & History, Columbia, SC; and Land Records, Miscellaneous, 1719–1820, Pt. 57, Bk. S4, 1775–1778, pp. 83–99, 24 August 1772, Charleston District and County Records, Charleston Public Library, Charleston, SC.

[14] For example, see South Carolina Weekly Gazette (Charleston, SC), 8 March 1783; City Gazette or the Daily Advertiser (Charleston, SC), 30 November 1790; and The State Gazette of South-Carolina (Charleston, SC), 27 October 1791.

[15] For other examples of this practice, see David W. Dangerfield, “Hard Rows to Hoe: Free Black Farmers in Antebellum South Carolina,” p. 58, master’s thesis, University of South Carolina, 2014; available online: https://www.mobt3ath.com/uplode/book/book-2186.pdf (accessed 8 August 2020).

[16] Charleston County Will Book, 1767–1771, Vol. 11, pp. 105.

[17] Miscellaneous Records, 1763–1767, 21 November 1763, Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939L-JGSG-JM?i=39&wc=M6N4-3TP%3A210905601%2C211220801&cc=1919417 (accessed 8 August 2020).

[18] “Register of Marriage Licenses Granted, December 1765, to August 1766,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, Vol. 22 (1921): 34 and Jervey, “Abstracts of Records of the Proceedings in the Court of Ordinary… ,” 248.

[19] Charleston County Inventories, 1732–1746, p. 134, microfilm, Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939L-J698-GB?i=101&wc=MP5M-2NG%3A190562801%2C190562802%2C190575301%2C190560104&cc=1911928 (accessed 8 August 2020).

[20] “Dwight, Hester, Of St. Johns Parish, Berkeley County, Widow, To Her Slave, Charles Cordes, Formerly Known As Plymouth, Manumission,” 16 September 1749, Miscellaneous Records, Series 213003, Vol. 002H, p. 101, South Carolina Department of Archives & History, Columbia, SC. Hester Cordes was “a young lady of great merit and fortune” who married Rev. Daniel Dwight, the rector of St. Johns, Berkeley Parish in April 1747 (The South-Carolina Gazette [Charleston, SC], 27 April 1747). She was at times recorded as “Esther Cordes,” which was also the married name of her mother. Rev. Dwight died a year after their marriage and was buried at Strawberry Chapel (Gravestone for Rev. Daniel Dwight, Strawberry Chapel Cemetery, Berkeley Co., SC; available online: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/29048794/daniel-dwight [accessed 8 August 2020]).

[21] The financial requirements for freedom were not unique to Gough and Cordes. Slave owners may have included in their last wills and testaments financial payments in their terms for emancipation as an indication that the freed individual could support themselves or as compensation to the estate for the value of the freed person. Dangerfield, “Hard Rows to Hoe,” 58, and “Dwight, Hester, Of St. Johns Parish, Berkeley County, Widow, To Her Slave, Charles Cordes… .”

[22] A. S. Salley Jr., ed., Register of St. Philips Parish Charles Town, South Carolina, 1720–1758 (Charleston, SC: A. S. Salley, 1904), 142; available online: https://archive.org/details/registerofstphil00stph (accessed 8 August 2020).

[23] The Cordes and Goughs of St. Johns, Berkeley Parish intermarried with another prominent Huguenot family, the Porchers. For an excellent overview of the African American woodworking families enslaved by the Porchers in St. Johns, Berkeley, see Katherine McCarthy Watts, “Decoding the Woodwork of White Hall: A Network of Enslaved Carpenters and French Huguenots,” MESDA Journal, 2020, Vol 41, online: https://www.mesdajournal.org/2020/decoding-the-woodwork-of-white-hall-a-network-of-enslaved-carpenters-and-french-huguenots/ (accessed 8 August 2020).

[24] Charleston County, Inventories, Vol. 82-A, 1753–1756, pp. 81–84, Civil Works Administration Transcripts, microfilm, Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC; available online https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939L-JZ9M-DV?i=68&wc=MPP1-K6X%3A190562801%2C190562802%2C190652701%2C190560104&cc=1911928 (accessed 8 August 2020) and Charleston County Will Book, 1752–1756, Vol. 7, pp. 83–86, Civil Works Administration Transcripts, microfilm, Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC; available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939L-J89C-WN?i=100&wc=M6N4-XZ9%3A210905601%2C211509901&cc=1919417 (accessed 8 August 2020).

[25] Charleston County, Inventories, Vol. 82-A, 1753–1756, p. 83. The authors fully recognize the issue of suggesting that “Child Johnny” could refer to the cabinetmaker John Gough. If he was the “Child Johnny” inventoried along with his mother in 1753, he was most likely quite young (probably five years of age at the oldest) in order to be coupled with his mother instead of listed separately. Such a theory would make him about fifteen years old in 1763 when he earned his freedom from Elizabeth Akin’s estate—not an impossibility, but also not very likely. It should be noted, however, that “Jane and Child Johnny” were assigned the value of £420, the second highest value placed on any of the people enslaved by Richard Gough (a man named Prince given a value of $450). Such a high value, even for both a mother and her son, suggests they were of some significance to the Gough family.

[26] Land Records, Miscellaneous, 1719–1820, Pt. 57, Bk. S4, 1775–1778, pp. 83–99, 24 August 1772, microfilm, Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC.

[27] Land Records, Miscellaneous, 1719-1820, Pt. 57, Bk. R4, 1775–1778, pp. 162–163, 21 December 1770.

[28] Land Records, Miscellaneous, 1719–1820, Pt. 63, Bks. A5–B5, 1776–1779, B5, pp. 77– 80, 16 and 17 March 1777.

[29] South Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser (Charleston, SC), 8 March 1783.

[30] South Carolina Gazette and General Advertiser (Charleston, SC), 6 April 1784.

[31] Charleston County, Mortgages, 1734–1822, No. E.E., 1777-1790, p. 18, 6 May 1774, microfilm, Department of Archives and History, Columbia, SC.

[32] South Carolina and American General Gazette (Charleston, SC), 19 December 1776.

[33] Charleston County, Mortgages, 1734–1822, No. H.H.H., 1789–1795, p. 105.

[34] Brunk Auctions, 14 September 2019, Lot 1085, online: https://brunkauctions.com/lot/important-signed-charleston-secretary-linen-press-3969150 (accessed 8 August 2020). In 1952 a physician in Charlotte, North Carolina acquired the secretary wardrobe from Connecticut antiques dealer (George Williams report, p. 4). Fifty-three years later the secretary wardrobe was acquired by dealer-scholar George Williams and the white chalk inscription (“John Go__h, John”) on the top of the lower case was first documented.

[35] There has been some discussion about a correct deciphering of the name in white chalk on the top board of secretary bookcase. The authors have concluded that the inscription does indeed reference the free Black cabinetmaker John Gough based on a number of indicators. Certainly, the first name appears to be “John” and the first letter of the last name is an uppercase “G” followed by a lowercase “o” and then three or four other letters. A search of Charleston cabinetmakers working in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries with the proper name John and a surname that begins with “G” resulted in only John Gough as a likely candidate (the others were John Greatreks [w.1804], John Gros [w.1804–c.1840], and John John Guppell [w.1703]). This lack of another “John G” cabinetmaker, evidence that the secretary wardrobe was indeed made in Charleston in the 1785 to 1795 period, and the placement of the signature (not a likely place for an owner to mark their furniture) all point to the name on the secretary wardrobe being “John Gough,” the free Black cabinetmaker working in Charleston.

[36] “Wardrobe” seems to be Charlestonian’s preferred term for this form in the late nineteenth century, supplanting the earlier “press” or “clothes press.” See Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Documentary Evidence for Furniture Forms and Terminology in Charleston, South Carolina, 1670–1820,” MESDA Journal, 2013 (Vol 34), online: https://www.mesdajournal.org/2013/documentary-evidence-furniture-forms-terminology-charleston-south-carolina-ii/#CasePressClothes (accessed 8 August 2020.

[37] For an example of Thomas Day’s furniture, see an 1850 dressing bureau in the MESDA collection (Acc. 5399), online: https://mesda.org/item/collections/dressing-bureau/20016/ (accessed 8 August 2020). For an outstanding analysis of John Hemmings’s work at Monticello and an attributed table he made for Poplar Forest, see Robert Self, “ ‘I Have a Job of 4. Pembroke Tables on Hand at Monticello’: Five Tables Made for Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest by Joiners James Dinsmore and John Hemmings,” MESDA Journal, 2020, Vol. 41, online: https://www.mesdajournal.org/2020/i-have-a-job-of-4-pembroke-tables-on-hand-at-monticello-five-tables-made-for-thomas-jeffersons-poplar-forest-by-joiners-james-dinsmore-and-john-hemmings/ (accessed 8 August 2020).

[38] The number of recorded Black cabinetmakers (seventy-three) can be viewed as both remarkably high due to a scarcity of documentation about free and enslaved craftspeople and exceedingly low because of the vast numbers of southern cabinetmakers who enslaved people but for whom no record exists.

[39] MESDA Object Database, record NN-838, online: https://mesda.org/item/object/desk-slant-top/18382/ (accessed 8 August 2020).

[40] John Bivins Jr., The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina (Winston-Salem, NC: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1988), 459 and MESDA Craftsman Database, record 50575, online: https://mesda.org/item/craftsman/burke-timothy-c-1811/50520/ (accessed 8 August 2020).

[41] James W. Hagy, People and Professions of Charleston, South Carolina, 1782–1802 (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing, 1992), 24.

[42] The placement of Boston’s signature and date was likely an intentional decision to hide his mark, suggesting that Boston was a worker in a shop and not the owner of the chest of drawers. See The Post and Courier (Charleston, SC), 17 February 2017; available online: https://www.postandcourier.com/news/hidden-signature-on-antique-acquired-by-charleston-museum-provides-rare-proof-of-early-african-american/article_cb93a0f4-f3ca-11e6-bfa5-5bea057a7f7c.html (accessed 8 August 2020).

[43] Gary Albert, “Probability and Provenance: Jacob Sass and Charleston’s Post-Revolution German School of Cabinetmakers,” MESDA Journal, 2015, Vol. 36, online: https://www.mesdajournal.org/2015/probability-provenance-jacob-sass-charlestons-post-revolution-german-school-cabinetmakers/ (accessed 8 August 2020).

[44] Rauschenberg and Bivins, Vol. II, 493–497 and 554–563. See also, John Bivins Jr., “The Convergence and Divergence of Three Stylistic Traditions in Charleston Neoclassical Case Furniture, 1785–1800,” American Furniture 1997, edited by Luke Beckerdite: 68–76; available online: http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/279/American-Furniture-1997/The-Convergence-and-Divergence-of-Three-Stylistic-Traditions-in-Charleston-Neoclassical-Case-Furniture,-1785–1800 (accessed 8 August 2020).

[45] MESDA Object Database, record S-6789, online: https://mesda.org/item/object/bookcase-library/14432/ (accessed 8 August 2020).

[46] A wardrobe and secretary bookcase in private collections are related to the library bookcase and were possibly made in the same shop. MESDA Object Database, records S-8433 and S-29209, online: https://mesda.org/item/object/wardrobe/14264/ and https://mesda.org/item/object/secretary/14434/ (accessed 8 August 2020).

[47] MESDA Object Database, record S-8996, online: https://mesda.org/item/object/wardrobe/14283/ (accessed 8 August 2020).

[48] Rauschenberg and Bivins, Vol. II, 563.

[49] Watson was the sole search result of the MESDA Craftsman Database for cabinetmakers known to have come from Scotland and working in Charleston in 1790; MESDA Craftsman Database, John Watson, record 42468, online: https://mesda.org/item/craftsman/watson-john/42262/ (accessed 8 August 2020). See also Rauschenberg and Bivins, Vol. III, 1283–1286.

[50] Rauschenberg and Bivins, Vol. III, 1286; Clare Jervey, Inscriptions on the Tablets and Gravestones in St. Michael’s Church and Churchyard, Charleston, S.C. (Columbia, SC: The State Company, 1906), 290.

[51] Rauschenberg and Bivins, Vol. III, 1284.

[52] Jervey, Inscriptions on the Tablets and Gravestones in St. Michael’s.

[53] Albert, “Probability and Provenance.”

[54] Rauschenberg and Bivins, Vol. III, 1284.

[55] Courier (Charleston, SC) 10 February 1813.

[56] See MESDA Craftsman Database, record 10918, online: https://mesda.org/item/craftsman/david-slave/10858/ (accessed 8 August 2020). See also, Rauschenberg and Bivins, Vol. III, 960.

[57] Charleston County, Mortgages, 1734–1822, No. H.H.H., 1789–1795, p. 105.

[58] The first five members were the founders of the Brown Fellowship Society; Gough was the first member to apply and be admitted. “Lists of Society Members Admitted, 1790 to 1844,” Brown Fellowship Society Records, 1790–1911, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC.

[59] Sarah Bartlett, “Brown Fellowship Society (1790–1945),” BlackPast.org, online: https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/brown-fellowship-society-1790-1945/ (accessed 8 August 2020).

[60] City Gazette or the Daily Advertiser (Charleston, SC), 30 November 1790.

[61] Ibid

[62] The State Gazette of South Carolina (Charleston, SC), 14 February 1791.

[63] Land Records, Miscellaneous, 1719–1820, Pt. 101, Bks. C8–D8, 1810–1811, D8, pp. 35–36, 11 February 1811.

[64] Rauschenberg and Bivins suggested that Margaret Cordes Gough may possibly have been alive in 1820 and was listed in that year’s United States Census. Checking a facsimile of the actual census page, however, reveals that the column marked for “M. Gough” is for a free African American male over the age of forty-five, with seven free African American females under the age of fourteen. Rauschenberg and Bivins, Vol. III, 1033 and 1820 United States Census, Charleston Neck, Charleston, SC, available online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YBW-DJ8?i=103&cc=1803955&personaUrl=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AXHL7-Z67 (accessed 8 August 2020).

[65] The outstanding work undertaken by the Black Craftspeople Digital Archive illustrates the profound need for deepening research into African American artists and artisans and wide dissemination of those findings. Black Craftspeople Digital Archive, online: https://blackcraftspeople.org (accessed 8 August 2020).

© 2020 Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts

![Fig. 20: Locations of Edinburgh and Musselburgh highlighted on a detail from the north center sheet of “Map of the Three Lothians” by Andrew Armstrong and Mostyn Armstrong and engraved by Thomas Kitchin, 1773, Edinburgh. Ink on paper; on map of six sheets; HOA: 34”, WOA: 60”. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland, shelfmark EMS.s.464 (online: http://maps.nls.uk (accessed 5 April 2016]).](https://www.mesdajournal.org/files/Gough_Fig_20_Thumb.jpg)