Alexandria’s tradition of stoneware manufacture is one of the great American ceramics stories. The broad outlines of stoneware made in Alexandria, Virginia have been put forth by scholars and collectors in the last fifteen years, but much more remains to be addressed, especially the roles played by enslaved and free African American potters.[1] The narrative of free African American potter David Jarbour is an important part of this story. From 1791 until 1847, the city of Alexandria was part of the District of Columbia. In the District of Columbia, enslaved African Americans could purchase their freedom and remain within the community, often working as skilled craftsmen. Jarbour purchased his freedom in 1820 and practiced his trade at the Wilkes Street Pottery in Alexandria.

The important role played by African American potters in American ceramics history has only recently been widely acknowledged. National recognition has been given to the enslaved potter David Drake of Edgefield, South Carolina and free black potter and entrepreneur Thomas Commeraw of New York City.[2] Yet the story of David Jarbour remains largely untold.

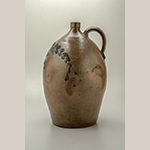

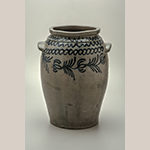

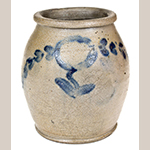

Signed and dated by David Jarbour, this jar at MESDA is one of the finest examples of southern salt-glazed, cobalt-decorated stoneware (Figures 1 and 2).[3] The storage jar serves as a Rosetta stone for developing a typology of his unsigned ceramics. Through a re-examination of the documentary evidence for Jarbour’s life and a stylistic analysis of pots attributed to him, this article illuminates the contributions of Jarbour and other free African American potters to the social and material landscapes of early nineteenth-century Alexandria.

Standing approximately twenty-eight-inches tall, with a diameter of fourteen-and-a-half inches at its widest point, the Jarbour storage jar is made of salt-glazed stoneware that was thrown in at least three sections. There is evidence of a horizontal join approximately half way up the sides of the jar below the lug handles on either side of the object and another join evident on the interior at the shoulder of the object. Kiln furniture ghost marks on the slightly-rolled rim suggest that another object was stacked on top of the jar in the kiln. Stacking as many objects as is safely possible in a kiln is common practice among potters. The weight of the additional object on top of the jar, however, accentuated the joint on the jar, resulting in a prominent sag or slump where the object’s sections meet.

Exuberantly painted cobalt floral and foliage decoration envelops the jar (see Figs. 1 and 2). One side of the object exhibits a large stylized tulip blossom with three petals and a central stem. Leafy fern-like fronds extend up each side of the central stem at forty-five degree angles. The other side of the jar bears an equally large flower resembling a stylized chrysanthemum. Although the blossom is different from the tulip, the leaves and central stem are clearly painted by the same hand. Frond-like shoots are painted below the lug handles and each handle is daubed with cobalt at the outer junctures. The rim of the jar is encircled with cobalt and the cobalt decoration on the body has areas of thin running drips that extend down to the foot—the direction of these drips reveals that the jar was fired right-side-up. Hidden on the underside of the flat wire-trimmed base is the incised inscription written in well-executed script: “1830 / Alexa / Maid By / D,, Jarbour” (Figure 3).[4]

Who Was David Jarbour?

It is unclear exactly when and where David Jarbour was born, but he is listed in the Free Negro Registers of Alexandria, District of Columbia, in 1821 as a black man of about thirty-three years of age, which means he was born in the late 1780s or early 1790s.[5] Some evidence points to St. Mary’s City as his place of birth.[6] This theory is based around the signature of potter Lewis Plum on Jarbour’s manumission record.[7] Plum, originally from St. Mary’s City, witnessed Jarbour’s emancipation document, suggesting he had a close relationship with Jarbour. Given their shared profession, it is very plausible that Jarbour trained with Plum. But it is unclear whether he trained with him in St. Mary’s City or in Alexandria.

Another theory is that Jarbour was actually born in Alexandria. In the 1790s a white woman named Cassandra Jarber resided in the city and married at the First Presbyterian Church, 2 January 1791, a man named Simpson Talbott.[8] More research is needed to determine Cassandra Jarber’s status and if she brought any enslaved individuals to her marriage. But since the spelling of her maiden name is one of the alternate spellings found in documents for David Jarbour’s surname, the theory should be considered.

We know more about Jarbour’s spouse, Rebecca. A search of Alexandria records reveals an African American woman named Rebecca Dover Jarbo who is listed in 1813 as David Jarbour’s wife and the daughter of Samuel and Betty Dover. In that same year a Quaker businessman named Ezra Kinsey testified on behalf of the Dover family stating that he had known the family for over twenty years and that “they have always been considered free.”[9]

What it meant to be considered free in nineteenth-century Alexandria is a dissertation topic in itself.[10] For the purposes of this article it should be noted that free African Americans residing within the city of Alexandria were mandated to carry registration certificates at all times in the event that their status was questioned. The inability or failure to present a certificate often resulted in imprisonment and the possibility of being sold into slavery. The law required both freeborn and emancipated African Americans to register at the courthouse or with the court and update that registration on a regular basis. (Figure 4) Within smaller and more rural communities this part of the legal system was sometimes overlooked; but in the bustling port of Alexandria the inspection of registration certificates was routinely enforced.[11]

In 1820, out of Alexandria’s population of approximately ten thousand, over thirteen percent were free blacks. By 1840 that percentage had increased to nearly nineteen percent.[12] This growth was almost certainly due to the influence of Quaker individuals and families within the city. The Quaker Ezra Kinsey ran a tanning business with his brother Zenas Kinsey. In addition to their business interests, the Kinseys were also involved in efforts to better Alexandria at large. They were instrumental in the workings of the Friendship Fire Company, which maintained the Friendship Fire Station at a central location within the city and provided fire protection to the surrounding businesses and neighborhoods (Figure 5).

The Kinsey (also spelled “Kinzey”) family was strategic in its efforts to assist the African American community. The Alexandria County Deed Book reveals that David Jarbour purchased his freedom from Zenas Kinsey, and the Free Negro Registers for the same county show that the Dover family, Jarbour’s wife’s family, was affirmed free by Ezra Kinsey.[13] Additionally, the Kinseys testified to the free status of other African Americans listed in the Free Negro Registers.[14] David Jarbour had at least five children with his wife Rebecca Dover, including David, Rachel, Samuel, Mary, and Chloe. All of their children were listed in the Free Negro Registers of Alexandria between 1838 and 1847 and most of them were affirmed to be free blacks by Zenas Kinsey (Figure 6).[15]

In addition to Quakers like the Kinseys, many free African Americans were instrumental in securing or maintaining the freedom of fellow freedmen in Alexandria. Some appeared as witnesses to the sales of enslaved African Americans who were guaranteed their freedom after a certain period of time.[16] Others witnessed emancipation documents, land deeds, and court documents, even providing character representation in bankruptcy cases. Spencer Gray was a free African American who was recorded in Alexandria newspapers and court documents as giving financial assistance to several free blacks. In his 1822 will, Gray left ten dollars “to my friend David Jarboe.”[17] The exact role that Spencer Gray played in David Jarbour’s life is yet to be determined, but he may have encountered Jarbour at the Wilkes Street Pottery where he worked, since Gray’s will was witnessed by one of Jarbour’s employers, Benedict C. Milburn (Figure 7).[18]

Alexandria and the Wilkes Street Pottery

Alexandria was an important port city in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Situated just below the fall line of the Potomac River, the city’s port was navigable by ocean-going ships and yet had easy access to the fertile lands and natural resources of the interior—including large clay deposits suitable for potting. The strip of shops and warehouses on the waterfront was known as the Strand. Contemporary artist Lewis Miller sketched a view of the city and wrote of Alexandria: “its Situation is Elevated and pleasant” (Figure 8). From the wharfs on the Strand, Alexandria’s businesses and manufactories extended inland perpendicular to the river, providing easy access for the movement of finished products between shops and wharfs on the waterfront (Figure 9). By the first quarter of the nineteenth century, Alexandria’s newspapers were running advertisements for turnpikes that connected that city’s manufacturing areas and port to inland communities such as Fauquier County west of Alexandria.

Alexandria was often referred to as “Little Philadelphia” because of its grid-layout seen clearly on the period plan published by I. V. Thomas in 1798 (Figure 10). The Quaker meeting house (denoted by the left green star in Fig. 10) is important to Jarbour’s story not only because of the significant role The Society of Friends played in Alexandria’s free African American community, but also for their establishment of the city’s two free black neighborhoods: Bottoms and Hayti (represented by the blue ovals in Fig. 10). Both the Bottoms neighborhood at South Alfred Street and the Hayti neighborhood at South Royal Street were created in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.[19]

The Wilkes Street Pottery (designated by the right green star in Fig. 10) was Alexandria’s center for ceramic production from 1813 until 1876. Ezra and Zenas Kinsey’s tannery was located diagonally across the street. This location five blocks from the Bottoms and Hayti neighborhoods provided access to the city’s free Black labor force. In addition to David Jarbour, there were at least fourteen other free African Americans who worked at the Wilkes Street Pottery.[20]

The Wilkes Street Pottery was managed by three different owners over its sixty-three-year operation. The first owner was John Swann; the second consisted of a variety of partnerships between entrepreneur Hugh Smith and his sons; and the third was Benedict C. Milburn. This ownership timeline is not as straightforward as it might first appear: Swann continued to work at the pottery during the Hugh Smith years and there was also overlap between the Smith years and those of Milburn, all of which makes the dating of pots and decoration a difficult endeavor.[21] Complicating the situation is the fact that the owners of the Wilkes Street Pottery did not actually make the pottery—any number of white and free and enslaved African American potters produced the wares that bore the proprietors’ names. Regardless, throughout the proprietorships of Smith and Milburn the “Alexandria flower” motif—as it is frequently referred to by collectors today—persisted in Wilkes Street Pottery production (Figures 11 through 16).

Looking closely at MESDA’s signed and dated jar, it is clear that Jarbour’s exuberant decoration deviates from the Alexandria flower motif (see Fig. 1). The decoration on the signed jar at MESDA may serve as a guide for attribution of other pots made and decorated by Jarbour that are not signed. The jar illustrated in Figure 17 is a good example. The same frond-like foliage, sweeping finger-like brush strokes, and, perhaps most notably, the presence of a central stemmed flower, enable us to attribute this exuberantly decorated storage jar to David Jarbour. By identifying these same characteristics on other pots, a decorative lexicon can be built for attribution of other objects and different forms with similar decoration such as Jarbour’s distinctive central stem and flower motif and his frond-like leaves.

The hand of the same decorator can also be seen on less profusely painted objects such as the bottle illustrated in Fig. 13 with a beautifully executed Alexandria flower motif. This object also bears an incised “D” on its base (Figure 18) that closely resembles the “D” in the script of Jarbour’s first name on the base of the MESDA jar (Fig. 3). Thus the presence of the incised initial “D” on the base, coupled with comparable materials and decoration, provides evidence for attributing an object to the hand of David Jarbour (Figure 19).

The inscribed “D” on the base of the MESDA jar links David Jarbour to his contemporaries working at the Wilkes Street Pottery and perhaps elsewhere in Alexandria. Another example of Wilkes Street Pottery, illustrated in Figure 20, also bears the initial of the potter’s first name on its base. In this instance a stamp was employed rather than incised script. The “T” stamped on the underside of the jar (Figure 21) was the mark used by enslaved African American potter Thomas Valentine who also labored at the Wilkes Street Pottery. Valentine should be the subject of another project entirely; but his jar suggests that the use of initial marks by the free and enslaved black potters at the Wilkes Street Pottery, and perhaps elsewhere in Alexandria, while not unique, is certainly noteworthy.[22]

Fauquier County Trade Connections and Alexandria’s Potteries

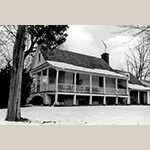

MESDA’s signed David Jarbour jar came into the museum’s collection in 1977 as a gift of Mr. and Mrs. Byron Banks, who were descendants of Henry and Frances Eleanor Smith of West View in Fauquier County, Virginia. Henry was the son of William Rowley Smith of Alton, another home in Fauquier County; and Henry built West View on land his father gave him when he reached twenty-one years of age. Completed around 1840, West View was of modest size with one-and-a-half stories on an English basement. But despite the modest size of the structure, it was constructed in the fashionable and imposing Greek Revival style (Figure 22).[23]

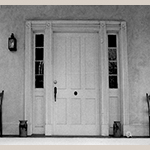

MESDA’s director and founder Frank Horton visited West View and Mr. and Mrs. Banks in the 1970s.[24] Over the course of the visit, according to an oral history, Horton noticed the storage jar lurking in a corner of the house’s cellar. Noting his interest in the object, Mrs. Smith interjected something along these lines: “That’s been there forever. If you’d like to take it, it’s yours.”[25] Curators and collectors alike are often skeptical of phrases such as “That’s been there forever.” In this instance it seems very plausible that the storage jar really had remained in the cellar for a century or more. A photo taken in the late 1970s by the Virginia Department of Historical Resources documented West View’s architecture and two Alexandria-made stoneware jars on either side of the front door (Figure 23).[26] Those same jars show up in similar photographs taken in the late 1990s (not illustrated). If the small, easily movable jars in those photos gave evidence to a twenty-year time lapse on a porch stoop, a one-hundred-and-fifty year stint in a cellar for a nearly forty-pound, abnormally large jar seems equally plausible.

The 1830 date on the underside of the signed jar’s foot raises the question of the object’s original owner. It could have been owned by the earlier generation of the Smith family and then gifted to Henry and Frances. Not surprisingly given the utilitarian nature of the jar, neither William Smith’s will and inventory nor Henry’s will and inventory provide proof for this theory. A single reference to “crockery ware” valued at $9.00 in Henry’s estate inventory suggests it may have been lumped into that entry.[27] Regardless, the existence of the jar raises the question: How did an Alexandria-made jar end up in a rural Fauquier County house sometime in the first half of the nineteenth century?

Fauquier County had a flourishing trade with Baltimore during the mid eighteenth century. Even though Alexandria was only sixty miles from Fauquier County, the Baltimore trade route provided an easier path for the shipment of goods until the construction of the Little River Turnpike and the Fauquier and Alexandria Turnpike in the first quarter of the nineteenth century. Those roadways opened up a closer market for Fauquier County residents and a new consumer base for Alexandria’s merchants.[28]

Alexandria businessmen were heavily involved with the turnpike.[29] One such person was Hugh Smith, who oversaw the Wilkes Street Pottery during part of Jarbour’s tenure there as a potter. Smith was involved in many business ventures in Alexandria and, in addition to being involved at the Wilkes Street Pottery, he was also a china merchant and dry goods seller. As an Alexandria entrepreneur, Smith served on the boards of several turnpikes and canals including the Fauquier County Turnpike. His involvement helped secure trade routes for his goods from the Wilkes Street Pottery and his other business endeavors, as well as figuratively and literally paving the way for a large storage jar signed by David Jarbour to travel west sixty miles from Alexandria to a house in Fauquier County.

Conclusion

The free African American potter and entrepreneur Thomas Commeraw of New York City and the enslaved potter David Drake of Edgefield, South Carolina have both received national recognition for their contributions to the history of American ceramics. David Drake is known for his ability to successfully throw very large pots and the poetry he composed and incised into them. Like David Drake, David Jarbour was also a master at his craft. The size of the signed piece in MESDA’s collection would be a feat for any potter; keeping its weight to a mere forty pounds bears testament to the skill needed to create such a large and thinly potted object.

The story of David Jarbour has only begun to unfold. There is still much more to learn about Jarbour, his family, and his pots. While the broad outlines of Alexandria’s stoneware history have been put forth by scholars and collectors during the last fifteen years, there is still much to discover. It is the hope of the author that this brief glimpse into what is currently known about David Jarbour will help bring more of his story and his pottery to light. If we listen to the objects and couple that information with the documentary evidence, we can better paint the unfinished portrait of Jarbour and so many other still unidentified enslaved and free African American artisans and craftsmen in our history.

While the author takes full responsibility for the information presented in this article, she wishes to thank the following for their invaluable assistance with the manuscript and the MESDA Summer Institute project that made it possible: Gary Albert, Kim Wilson May, the MESDA Journal Editorial Board, the MESDA Summer Institute Cass of 2016, Susan and Bill Mariner, Robert Leath, Carroll Van West, Daniel Ackermann, Michele Doyle, Suzanne Findlen Hood, Rob Hunter, Ron Hurst, Chris Jones, June Lucas, Barbara Magid, Zara Phillips, Susan Shames, Janine E. Skerry, and Brandt and Luke Zipp.

Angelika Kuettner is the Associate Curator of Ceramics & Glass at Colonial Williamsburg. She can be contacted at [email protected].

[1] In particular, see Eddie L. Wilder, Alexandria, Virginia Pottery, 1792–1876 (Marceline, MO: Walsworth Publishing, 2007). See also Barbara H. Magid, “ ‘Stone-ware of excellent quality, Alexandria manufacture’ Part I: The Pottery of John Swann,” Ceramics in America 2012, edited by Robert Hunter (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2012); available online: http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/524/Ceramics-in-America-2012/“Stone-ware-of-excellent-quality,-Alexandria-manufacture”-Part-I:-The-Pottery-of-John-Swann (accessed 29 May 2020)

and Barbara H. Magid, “ ‘Stone-ware of excellent quality, Alexandria manufacture’ Part II: The Pottery of B. C. Milburnnn,” Ceramics in America 2013, edited by Robert Hunter (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2013); available online: http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/539/Ceramics-in-America-2013/“Stone-ware-of-excellent-quality,-Alexandria-manufacture”-Part-II:-The-Pottery-of-B.-C.-Milburnnn (accessed 29 May 2020).

[2] See Brandt A. Zipp, “Washington, D.C. Stoneware,” Antiques and Fine Art, December 2012; available online: http://www.afanews.com/articles/item/1451-washington-dc-stoneware#.V3rXUlQrLIU (accessed 29 May 2020); Eve M. Kahn, “Slave Potter’s Presence Emerges in Fragments.” New York Times, 30 August 2012; available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/31/arts/design/pottery-by-david-drake-a-slave-craftsman-in-edgefield-sc.html (accessed 29 May 2020); and Jill Beute Koverman, editor, “I made this jar…”: The Life and Works of the Enslaved African-American Potter, Dave (Columbia: McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, 1998).

[3] MESDA Collection, Acc. 2964, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Byron J. Banks; available online: https://mesda.org/item/collections/jar/1477/ (accessed 29 May 2020).

[4] The signature on the base of the jar is only one of the spellings found in period documents for the surname Jarbour. The written evidence contains at least seven different spellings including “Jarbour,” “Jarbor,” “Jarber,” “Jarboe,” “Jarbo,” “Tarbor,” and “Garber” found in research thus far.

[5] Dorothy S. Provine, Alexandria County, Virginia Free Negro Registers 1797–1861 (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 1990).

[6] Author’s conversations and email correspondence with Christopher H. Jones, July 2016.

[7] Alexandria Deed Book K-2, p. 205, records of the Alexandria Circuit Court, Alexandria, VA.

[8] Wesley E. Pippenger, Marriage and Death Notices from Alexandria Newspapers (Arlington, VA: W. E. Pippenger, 2005).

[9] Provine, Alexandria County, Virginia Free Negro Registers 1797–1861.

[10] For example, see Eric Foner, “The Meaning of Freedom in the Age of Emancipation,” The Journal of American History, Vol. 81, No. 2 (September 1994): 435–460.

[11] See Harold W. Hurst, Alexandria on the Potomac: The Portrait of an Antebellum Community (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1991).

[12] Ibid. See also Leonard P. Curry, The Free Black in Urban America, 1800–1850: The Shadow of the Dream (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, 1986) and Provine, Alexandria County, Virginia Free Negro Registers 1797–1861.

[13] For Jarbour and Dover entries, see Alexandria Deed Book K-2, p. 205 and Provine, Alexandria County, Virginia Free Negro Register 1797-1861.

[14] The Kinsey family’s association with at least thirty registration records, witnessing large families in several instances, can be found in Provine, Alexandria County, Virginia Free Negro Registers 1797–1861.

[15] Chloe Jarbour’s affidavit was substantiated by B. C. Milburne, who ran the Wilkes Street Pottery, 1841–1876.

[16] Pamela Cressey, “Early 1800s Saw Rise of Free Black Society,” Alexandria Gazette Packet, 16 February 1995. Cressey, the Alexandria City Archaeologist, discusses free mulatto William Goddard’s role in emancipating and preserving the freedom of African Americans in Alexandria.

[17] Will of Spencer Gray, dated 20 November 1822 and probated 10 December 1822, Alexandria County Will Book K, 1821-1831, p. 78. See Fig. 7 for an image of the document.

[18] The Alexandria Gazette records that David Jarbour filed for bankruptcy in 1825, three years after Spencer Gray’s death. The bankruptcy may have been the culmination of earlier financial difficulties during which Gray would have been alive to assist. It is interesting to note that Spencer Gray was an executor for William Goddard’s will (see Cressey, “Early 1800s Saw Rise of Free Black Society”).

[19] For more on these communities, see To Witness the Past: African American Archaeology in Alexandria, Virginia, Catalogue of an Exhibition (Alexandria, VA: Alexandria Archaeology, 1993).

[20] This number tallied from the Alexandria County Registers; Magid, “ ‘Stone-ware of excellent quality, Alexandria manufacture’ Part I: The Pottery of John Swann,” 111–145; and To Witness the Past: African American Archaeology in Alexandria, Virginia.

[21] For additional information and the archaeological evidence recovered at the potteries, see Magid, “‘Stone-ware of excellent quality, Alexandria manufacture’ Part I: The Pottery of John Swann,” 111–145. Magid adeptly explains the different eras of the pottery, closely examining the archaeological finds and pairing those finds with intact above ground examples.

[22] For a brief look at the career and work of Thomas Valentine, see Magid, “ ‘Stone-ware of excellent quality, Alexandria manufacture’ Part I: The Pottery of John Swann,” 111–145. See also the Crocker Farm Auction record available online: https://www.crockerfarm.com/stoneware-auction/2019-07-20/lot-129/Very-Rare-and-Important-Alexandria-VA-Stoneware-Jar-att-African-American-Potter-Thomas-Valentine/ (accessed 29 May 2020). Thomas Valentine had purchased his freedom by 1831 when he and David Jarbour signed a petion of the “free colored inhabitants of the Town of Alexandria… .” The petition was published in the Alexandria Phenix Gazette, 4 October 1831, p. 2.

[23] Kimberley Prothro Williams, A Pride of Place: Rural Residences of Fauquier County, Virginia (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 2004) and Fauquier County, Virginia 1759–1959 (Warrenton, VA: Fauquier County Bicentennial Committee, 1959).

[24] The Bankses were a philanthropic couple with a dedication to historical preservation. Mrs. Banks was on the Board of Directors of the Fauquier County Historical Society and gave objects and loans for the society’s exhibits in the early 1980s. See News and Notes from The Fauquier County Historical Society, Vol. 7, No. 3 (Summer 1985): 4–5.

[25] Information from the MESDA accession files and author’s conversations with Bradford L. Rauschenberg, MESDA’s emeritus director of research, July 2016.

[26] Virginia Historic Registers, ID: 030-0528, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Richmond, VA.

[27] Fauquier County Will Book 38, 1883–1886, Fauquier County Clerk’s Office, Warrenton, VA.

[28] The Little River Turnpike is modern-day State Road 236.

[29] Michael T. Miller, Portrait of a Town: Alexandria, District of Columbia [Virginia] 1820–1830 (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 1995), 78–84.

© 2020 Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts