Much scholarship in recent years has shed light on enslaved potters working in the American South, most notably David Drake and other African Americans working in the Edgefield District of South Carolina.[1] Aside from recent scholarship by Angelika Kuettner on the free Black potter David Jarbour, little attention has been given to the number of free people of color who worked as potters in a slave economy before the American Civil War.[2] One such free Black potter was a man named Abraham Spencer who worked in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, probably alongside several of the Valley’s well-known white potters.

Although few pieces of pottery survive that can be attributed to Abraham Spencer, numerous records document his life, the lives of his family, and the people with whom the Spencer family interacted (Figure 1). The goal of this article is to gather surviving documentation of Spencer’s life and career, illustrate the extant pottery that can be attributed to his hand, and provide context for his life and work. By doing so it is hoped that this research note will, firstly, broaden awareness and appreciation of Abraham Spencer’s accomplishments as a skilled free person of color in a slave economy and, secondly, inform further research about Black potters working in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley during the nineteenth century.

Born into Freedom

On 3 February 1803, Abraham Spencer’s father, an enslaved man named Jesse Spencer, was emancipated by Robert Carter III in Frederick County, Virginia (Figure 2).[3] In 1791, Carter, a large slaveholder and descendant of one of the wealthiest landowners in America, set into motion the gradual emancipation of over four hundred people.[4] By 1806 seventy-two individuals enslaved by Robert Carter III were emancipated in Frederick County, and many remained in the area.[5] Jesse Spencer was among them.

Along with his parents, Sukey Spencer and Robbin Spencer, as well as several other family members, Jesse Spencer was enslaved at Cancer, a Carter plantation located outside of Richmond, Virginia. Carter named many of his plantations after astrological signs including Capricorn, Sagittarius, Aquarius, and Libra.[6] Cancer was one of Carter’s smaller plantations. Nine people were enslaved there in 1791, four of whom were adults.[7] Though wheat, pork, and tobacco were produced at Cancer, it may not have been a successful plantation.[8] In 1787, William Brickey wrote a letter to Carter relinquishing his claim to becoming overseer at Cancer Plantation, including notes about the Spencer family:

I find there not any Tobacco Land neither is there any chance for wheat, not is there any chance of raising any profit from any thing [sic] but the corn…as for the hands that is there which is Robin & Sucke and their Children I would not have as a compliment for the next year, for I believe their Incumbrance would be more Charge, than the profit of their work… .[9]

In 1796, Robert Carter III turned all of his properties over to his children, leaving Cancer to his daughter Betty Landon Ball and her husband Spencer Ball. In 1797, Carter signed a deed of trust in which he detailed that Baptist minister Benjamin Dawson would “own” his remaining slaves at the price of one dollar in order for Dawson to facilitate their emancipation.[10]

The timing of Jesse Spencer’s emancipation in 1803 provided him an additional freedom. In 1806 the Virginia legislature passed a law, called “The Removal Law,” requiring that individuals who were emancipated after 1 May 1806 and who stayed in Virginia for a year would lose their freedom and could be “apprehended and sold by the overseers of the poor or corporation in which he shall be found for the benefit of the poor of such county or corporation.”[11] Because his emancipation came three years before enactment of the Removal Law, Jesse Spencer was not required to petition to remain in the state.

Abraham Spencer was born sometime around 1806 to Jesse and Mary Spencer.[12] The family was living in Winchester, Virginia at the time and Jesse was recorded in tax lists as a laborer.[13] On 9 November 1809, a deed between Anthony Shomo and his wife as one party, and Jesse Spencer and Dennis Johnson as the other party, recorded the purchase of a quarter acre of land in the town of New Market in Shenandoah County, noted as “Lot Number 13.”[14]

Dennis Johnson, also formerly enslaved by Robert Carter III, was freed two years before Jesse Spencer, and listed as a hostler in Frederick County between 1804 and 1809.[15] Jesse Spencer’s sister, Molley Spencer, was emancipated in the same document as Dennis Johnson in Frederick County; another sister, Hannah Spence[r], was emancipated in Frederick County in 1800.[16]

In 1823, when he was fifteen years old, Abraham Spencer was apprenticed to Henry Forrer to “learn farming.”[17] This apprenticeship may have been an effort by the Spencers to protect their child from Virginia’s treacherous slave laws. Beginning in 1820, the Overseers of the Poor in Virginia were required to investigate the condition of freed people and “unless it shall appear that by their own labor they procure sufficient means for subsistence, they shall be deemed vagrants.”[18] Vagrants could be forced out of Virginia or sold into slavery. To protect free Black children from this law, many were bound out at very young ages through indentures or apprenticeships.[19]

It is likely that at some point Abraham Spencer was bound out to begin an apprenticeship with a potter. This conclusion stems from the fact that there is no evidence that Abraham Spencer learned the skills of a potter from his immediate family since none of them are known to have practiced that trade. Instead, Spencer probably learned his trade while apprenticed to a neighbor, most likely a potter named George Bodel or Jacob Adam.

Sometime around 1806 the potter John Brouse purchased the New Market lot immediately adjacent to the one that would be bought by Jesse Spencer and Dennis Johnson.[20] Brouse was likely producing pottery on the site, and on 13 May 1811 he sold the lot to another potter, Jacob Adam, before moving to Canton, Ohio.[21] Jacob Adam was from Hagerstown, Maryland and his brother, Christian Adam, was also a potter who moved to New Market from Hagerstown. Jacob Adam operated a pottery in New Market lot until the 1830s (Figure 3). Although Jacob Adam sold his pottery property in 1837 to George Bodel, it is almost certain that Bodel had been leasing and working at the pottery prior to 1837 because Bodel appeared in New Market beside Jesse Spencer in the 1820 United States Census.[22] Thus Bodel would have been the potter working next door to the Spencers when Abraham Spencer was a child and is therefore the man most likely to have trained him in the trade.

Joseph Martin described New Market in his 1835 New and Comprehensive Gazeteer of Virginia as “…perhaps no town in the state of the same size, where the mechanical pursuits are carried on to a greater extent than in this.” He noted that the town had “two potteries, at one of which stone ware of a superior quality is manufactured” (Figure 4).[23] By 1840, New Market had at least five potters operating there, including George Bodel, Washington Windle, Branson Oraark, John Coffman, and a previously undocumented potter named John Hoffman.[24] The potters of New Market made salt-glazed stoneware, as mentioned by Martin, as well as lead-glazed earthenware. Some of the decorating traditions found on New Market’s pottery, such as a swirled slip surfaces, were likely carried over from Hagerstown by the Adam brothers (Figures 5 and 6).

On 5 May 1830, Margaret Spencer purchased a quarter-acre New Market town lot, Lot 13, for $1,000 from Jesse Spencer of Shenandoah County and Dennis Johnson of Frederick County.[25] Margaret Spencer was likely either a daughter or sister-in-law of Abraham Spencer, her exact relationship is ambiguous in the records. Following the sale of Lot 13 in 1830, Abraham Spencer’s father, Jesse, may have come into financial difficulties. In an 1835 “List of Free Negroes” in Shenandoah County, Jesse Spencer was noted as a male, aged sixty, but “Bound to Joseph Sibert,” perhaps to pay off debts.[26] In 1837, Joseph Sibert took in a young woman, possibly one of the sisters of Abraham Spencer, Sirene Spencer, in order to “learn spinning, cooking, and cleaning and to ascertain her age.”[27]

On 8 September 1829, a year before his father and Dennis Johnson sold New Market Lot 13, Abraham Spencer registered himself in Shenandoah County as a “free negro”; however, by the time the 1830 United States Census was conducted Abraham Spencer does not appear to be living in any household with the last name of Spencer.[28] Perhaps Abraham was working and living with a potter elsewhere in Shenandoah County. One possibility is Daniel Coffman, most likely a relative of potters John Coffman or Andrew Coffman. The 1830 Census recorded two free Black males, aged ten to twenty-four years, in Daniel Coffman’s household in the Western District of Shenandoah County (considered the New Market area). Abraham Spencer may have been one of those two men in Coffman’s household.

“…for this great and growing Evil…”

The 1831 Nat Turner slave rebellion in Southampton County, Virginia gave rise to a bevy of new laws created to regulate the lives of both free and enslaved African Americans. These new laws prohibited education and assembly and further restricted movement within and outside of counties and the commonwealth.[29] An 1833 slave law was passed to decrease the population of free people of color in Virginia. The act stipulated that $18,000 would be appropriated annually for five years to pay for the transportation of “free persons of color to or in Liberia or other places on the western coast of Africa by the American Colonization Society.”[30] Four years after the law was enacted, the white residents of Frederick County were not satisfied with the law’s implementation and on 12 February 1837 submitted a petition that “…we regard the residence of the free black population among us as highly injurious & deprecate its increase as an intolerable burden… .”[31] That same year white residents of Shenandoah County, where both Abraham Spencer and Jesse Spencer were presumably residing, submitted the following petition:

…the undersigned Citizens of the County of Shenandoah, Respectfully represent to your Honorable Body: That we regard the residence of the free black population, among us as highly injurious, both to us and to themselves, and do deeply deprecate the increase of an evil so stunning…the conviction that the existing Laws on this very important subject are Inadequate, do Respectfully invite the attention hoping that your evidence may provide a more certain remedy for this great and growing Evil… .[32]

These petitions also called out what the white citizens saw as an error of the legislature in that the laws requiring people freed from slavery to leave the Commonwealth only applied to those freed after 1806. This law did not apply to people freed prior to 1806, which included the hundreds of slaves emancipated by Robert Carter III, as well as children who were born to parents freed before 1806. Sporadic raids throughout Virginia during the 1830s targeted free people of color.[33] These types of raids, combined with the agitated citizenry of the counties they were living in, were almost certainly among the reasons that by the 1840s Jesse Spencer and Abraham Spencer left New Market and thereafter moved frequently.

In the 1840 United States Census Jesse Spencer is listed as living beside a free black barber named Prince Henry in Woodstock, Virginia. Prince Henry also had a store and perhaps a tavern as well based on surviving receipts showing a variety of services that ranged from shaving and trimming hair to boarding horses to the sale of goods including oysters, cakes, candy, and pints of cider. Tax records show that Prince Henry was taxed in 1840 for “2 free negroes” at $2.00 and taxed fifty-three cents for two lots in the town of Woodstock.[34] Jesse Spencer may have been working for Prince Henry because sometime after Henry’s death in the mid-1840s Spencer returned to New Market. In 1850 he was recorded living back at Lot 13 in Margaret Spencer’s household, but without any person named Rebecca (the name of a woman that Jesse had married in 1839) or any of the young children listed as living in his Woodstock household in 1840.[35]

Abraham Spencer appeared in personal property tax records for Frederick County in 1843 and 1844 in the district of Sydnor.[36] In 1850, Spencer and a man named Benjamin Howard were listed in the personal property tax lists in the district of Carson for Frederick County.[37] A year later an “Abm Spencer,” age forty-two, was noted as a free Black potter in the 1851 Winchester, Virginia personal property tax lists. Also recorded on the 1851 Winchester tax lists was twenty-four-year-old Benjamin Howard, a free person of color and a potter.[38] Howard was not a common surname in Frederick and Shenandoah counties during the mid nineteenth-century and many of the Howards who were living there at the time appear to have been people of color. A man named Harry Howard was the first free African American registered in Shenandoah County in 1803 following a law passed in 1801 requiring an annual list of all free people of color within each district with “name, sex, place of abode, and trade.”[39]

Throughout the 1850s Abraham Spencer and Benjamin Howard were recorded on the personal property tax rolls in the same districts of Frederick County: Carson district through 1851, Sangster in 1852, Barnes from 1853 to 1855, and then in Hale district through the end of the decade.[40] Abraham Spencer (sometimes listed as “Spence”) appeared several times on Frederick County registers in the early 1850s under the heading of not able to pay taxes. He and others were listed with their occupations and were required to work or be hired out to pay off their taxes.[41] Spencer was also registered in Shenandoah County in 1854, perhaps alluding to the possibility of his being employed by a pottery there.[42]

The 1860 Census places Abraham Spencer in Harrisonburg, Virginia, located in Rockingham County, living beside Thomas Logan. Both Abraham Spencer and Thomas Logan have “Potter” listed as their occupations. Thomas Logan was a native of Ireland and may have immigrated around 1820 to Harrisonburg.[43] Maria Carr, who grew up in Harrisonburg, Virginia and was born in 1812, described the pottery of Thomas Logan as such:

…Mr. Logan’s Pottery which was due E. from Mr. Bushnell’s house – Mr. Logan at that time supplied all the people with milk and butter pots. They were made of clay – and were the color of light terra-cotta when burnt… .[44]

Likely only making utilitarian lead-glazed earthenware as described, no known pieces of pottery attributed to Thomas Logan survive. At the same time as the 1860 Census record from Harrisonburg, Virginia, Abraham Spencer was also documented in tax records as registered in the district of Hale in Frederick County, Virginia, as was Benjamin Howard. Again, this alludes to the likelihood of Spencer having been employed by more than one potter in separate counties. What is known for certain is that by the 1860s and into the 1870s Abraham Spencer was working at least some of the time in Solomon Bell’s pottery located in the town of Strasburg, Shenandoah County.[45]

Attributed Pottery

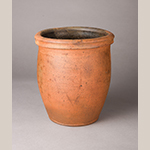

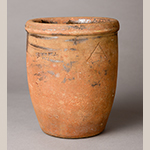

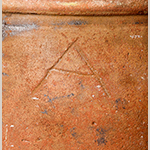

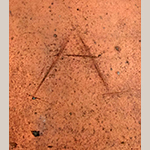

There are no known pieces of pottery fully signed or directly associated with Abraham Spencer. Several pieces exist with incised “A” marks on the sides, sometimes upside down. These marks were made prior to the initial kiln firing.[46] See Figures 7 and 8 for an example. Another jar (Figure 9) is similar in style and form to those made in the New Market, Virginia area in the second and third quarters of the nineteenth century. Another surviving piece of pottery is stamped “SOLOMON BELL / STRASBURG” (Figures 10 and 11) and incised with an “A” similar to the earthenware crock illustrated in Fig. 7 (see Figures 12 and 13 top compare the incised marks). Comstock stated that the examples featuring an incised “A” as well as a stamp of the Bell pottery are “usually distinguishable from most products made by the Bells,” so it perhaps possible to separate the work made by Abraham Spencer while he worked at the Bell pottery after the Civil War.

In 1929 Alvin H. Rice and John Baer Stoudt noted in their book The Shenandoah Pottery that Abraham Spencer, when working with the Bell family, had made his own ware to fire in the Bell pottery kiln and sell for his own profit.[48] Perhaps the pottery associated with this incising denoted Spencer’s work made for the Bell’s in exchange for making his wares in their shop and firing in their kiln. The crock in Fig. 7 may have been made earlier than that the one illustrated in Fig. 10 but may allude to a similar arrangement that Spencer had with another potter, perhaps in the New Market area.

Conclusion

Abraham Spencer died in 1873.[47] In 1915, his daughter, Serena Spencer (Figure 14), was interviewed about her experiences as witness to the American Civil War battle of Cedar Creek. Abraham Spencer and his family were living in the nearby town of Middletown in October 1864 when the battle occurred. Serena Spencer noted that her father “was free, and so was the rest of us,” including her mother and five siblings. They lived in “a log cabin on a back street jis’ across the road from Mr. Wright’s.”[49] She also described her father physically, stating that he “was a man that weighed nearly three hundred pounds, but he toddled around lively” on the morning of the Battle of Cedar Creek.[50]

Another description of Abraham Spencer came from interviews collected by Rice and Stoudt for The Shenandoah Pottery. In a passage describing workers who supported the pottery of the Bell family in Strasburg, the authors mistakenly recorded that after “his freedom” Abraham Spencer came to work for the Bells, and also noted that “Abe” referred to Samuel Bell as “my master.”[51] Of course this is incorrect because Abraham Spencer was born a free man. Spencer likely remained in Middletown while working for the Bells. As late as 1867 an account book for Brinker and Harris, merchants in Middletown, recorded “Abe Spencer, col[ored]” purchasing sugar, coffee, and butter.[52] He most likely traveled the six miles or so each way from Middletown to Strasburg to work at the Bell pottery. Abraham Spencer’s last residence can be found in the 1870 United States Census where he and his wife Henrietta were listed as living in Opequon, Frederick County, Virginia.

A descendent of an emancipated father and enslaved ancestors, Spencer died in 1873 and left a legacy amongst the potters in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. While he may have operated his own business, few pieces of pottery survive that can be attributed to his hands. According to his daughter he was a large man in stature, but his ambition, work ethic, and capabilities as a potter far outweighed his physical presence. Most importantly, Abraham Spencer is noteworthy for the potters with whom he worked—both Black and white—and his ability to successfully navigate life as a free person of color and a craftsman in a slave economy.

Brenda Hornsby Heindl is an independent scholar, working potter, and founder of Liberty Stoneware. She can be contacted at [email protected].

[1] An abbreviated list of articles presenting scholarship about enslaved potters in the South includes:

• Corbett Toussaint, “Edgefield District Stoneware: The Potter’s Legacy,” MESDA Journal, 2020 (Vol. 41).

• Arthur F. Goldberg and James Witkowski, “Beneath his Magic Touch: The Dated Vessels of the African-American Slave Potter Dave” in Ceramics in America, 2006, edited by Robert Hunter (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2006); available online: http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/281/Ceramics-in-America-2006/Beneath-his-Magic-Touch:-The-Dated-Vessels-of-the-African-American-Slave-Potter-Dave (accessed 20 January 2021).

• Barbara H. Magid, “Alexandria, Virginia” in Ceramics in America, 2017, edited by Robert Hunter and Angelika R. Kuettner (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2017); available online: http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/772/Ceramics-in-America-2017/?s=enslaved (accessed 20 January 2021).

• Martha A. Zierden et al., “Charleston, South Carolina” in Ceramics in America, 2017, edited by Robert Hunter and Angelika R. Kuettner (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2017); available online: http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/773/Ceramics-in-America-2017/Charleston,-South-Carolina(accessed 20 January 2021).

• Claudia Arzeno Mooney, April L. Hynes, and Mark M. Newell, “African-American Face Vessels: History and Ritual in 19th-Century Edgefield” in Ceramics in America, 2013, edited by Robert Hunter (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2013); available online: http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/537/Ceramics-in-America-2013/African-American-Face-Vessels:-History-and-Ritual-in-19th-Century-Edgefield (accessed 20 January 2021).

• Philip Wingard, “From Baltimore to the South Carolina Backcountry: Thomas Chandler’s Influence on 19th-Century Stoneware” in Ceramics in America, 2013, edited by Robert Hunter (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2013); available online: http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/538/Ceramics-in-America-2013/From-Baltimore-to-the-South-Carolina-Backcountry:-Thomas-Chandler’s-Influence-on-19th-Century-Stoneware (accessed 20 January 2021).

• Barbara H. Magid, “ ‘Stone-ware of excellent quality, Alexandria manufacture’ Part I: The Pottery of John Swann” in Ceramics in America, 2012, edited by Robert Hunter (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2012); available online: http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/524/Ceramics-in-America-2012/“Stone-ware-of-excellent-quality,-Alexandria-manufacture”-Part-I:-The-Pottery-of-John-Swann (accessed 20 January 2021).

• John A. Burrison, “Fluid Vessel: Journey of the Jug” in Ceramics in America, 2006, edited by Robert Hunter (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2006); available online: http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/285/Ceramics-in-America-2006/Fluid-Vessel:-Journey-of-the-Jug (accessed 20 January 2021).

• Mark M. Newell with Peter Lenzo, “Making Faces: Archaeological Evidence of African-American Face Jug Production” in Ceramics in America, 2006, edited by Robert Hunter (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2006); available online: http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/287/Ceramics-in-America-2006/Making-Faces:-Archaeological-Evidence-of-African-American-Face-Jug-Production (accessed 20 January 2021).

[2] Angelika Kuettner, “…my friend David Jarboe…”: The Unfinished Portrait of an Alexandria Potter,” MESDA Journal, 2020 (Vol. 41), online: https://www.mesdajournal.org/2020/my-friend-david-jarboe-the-unfinished-portrait-of-an-alexandria-potter/ (accessed 20 January 2021). See also Barbara H. Magid, “Alexandria, Virginia” in Ceramics in America, 2017, edited by Robert Hunter and Angelika R. Kuettner (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2017); available online: http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/772/Ceramics-in-America-2017/?s=enslaved (accessed 20 January 2021).

[3] John Randolph Barden, “Flushed with Notions of Freedom: The Growth and Emancipation of a Virginia Slave Community, 1732–1812,” doctoral dissertation (Duke University, 1993), 536. Entry reads, “Jesse Spence Born 1782. Son of Sukey Spence and Robin Spence. Residing at Cancer/Richmond in 1782, 1789, 1790, 1791, and 1796. Named in 1791 deed of emancipation. Scheduled for emancipation in 1803. Emancipated by deed dated January 1, 1803; deed proved in Frederick County Court, February 1, 1803.”

[4] Andrew Levy, The First Emancipator: The Forgotten Story of Robert Carter, the Founding Father Who Freed His Slaves (New York: Random House, 2005), 144–145.

[5] Rebecca Aleene Ebert, “A Window on the Valley: A Study of the Free Black Community of Winchester and Frederick County, Virginia, 1785–1860,” master’s thesis (University of Maryland, 1986), 12–13.

[6] Levy, The First Emancipator, 75, 121–122.

[7] Barden, “Flushed with Notions of Freedom,” 463, Appendix 12 (“Occupations within the Nomony Hall Community, 1791”). Cancer Plantation in Richmond was noted as having nine slaves: two children under the age of five; three children aged six to ten years; and four enslaved laborers considered agricultural workers or occupation unknown. No artisans or special task workers were listed as working at Cancer. It is not clear how or why a number of the enslaved individuals at Cancer, located in Westmoreland County, were emancipated in Frederick County. A possibility is that Cancer Plantation was sold following Robert Carter’s death and those yet-to-be-emancipated enslaved people were relocated to a plantation in Frederick County.

[8] Robert Carter, Account Book, 1785–1792, manuscript, pp. 12–13 and 105, VHS Mss1C2465a7, section 5, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, VA. Two houses were built at Cancer Plantation in 1787 under the entry of overseer William Fleming. Peter Bricky and William Brickey paid for one year’s rent at Cancer on 31 December 1789.

[9] William Brickey, Letter, “William Brickey, his letter relinguishing his Claim to Cancer Plantation, August 11, 1787,” VHS Mss1C2468a223, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, VA.

[10] Levy, The First Emancipator, 159 and Robert Carter, Land Book, 1802, manuscript, p. 11, VHS Mss1C2465a9, section 7, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, VA. Carter’s land book reveals ownership of the plantation called “Cancer” outside of Richmond by his daughter, Betty Landon Ball, and a note that “the two last named Plantations, the Forest & Cancer, are part of a Tract commonly called Cary’s Tract.”

[11] Ebert, “A Window on the Valley,” 32–33.

[12] Abraham Spencer’s estimated birth date has a wide variation based on the ages he gave during census and tax recordings. The birth year of 1806 is an estimation based on the average time frame for all of the ages in these documents. His mother, Mary, most probably died before 1839 when Jesse Spencer was recorded marrying Rebecca Moore (Marriage record for Jesse Spencer and Rebecca Moore, 24 December 1839, “Virginia Marriages, 1785-1940”, database, FamilySearch.org, online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XR76-X5X (accessed 20 January 2021).

[13] Joy MacDonald, Free Blacks on the Personal Property Tax Lists of Winchester City, Virginia, 1789–1862 (Athens, GA: New Papyrus, 2013), 212. Jesse Spence was noted on personal property tax lists of Winchester, Virginia in 1806 and 1807, noted as a laborer and in location of Kent.

[14] Shenandoah County, Virginia, Deed Book R, 1809–1810, 9 November 1809, p. 394, microfilm, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[15] Ebert, “A Window on the Valley,” 13 (Table 2) and 25. Dennis Johnson was listed as a hostler in 1804, 1807, and 1809; Frederick County, Virginia, Deed Book 27, 1800–1803, p. 134, microfilm, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[16] Barden, “Flushed with Notions of Freedom,” 539, 586. Entry for Molley Spence (p. 539): “Born 1782. Daugher of Sukey Spence and Robin Spence, granddaughter of Payne. Residing at Cancer/Richmond in 1784, 1789, 1790, 1791, and 1796. Nursed by her grandfather in 1784. Named in 1791 deed of emancipation. Scheduled for emancipation in 1801. Emancipated by deed dated January 1, 1801; deed proved in Frederick County Court, February 2, 1801.” Entry for Hannah Spence (p. 586): “Born 1769. Parents unknown (perhaps related to Robin Spence; mother of Dennis. Formerly at Dickersons Mill; residing at Virgo in 1788, at Scorpio in 1791 and 1796. Valued at 55 pounds in 1785. Named in 1791 deed of emancipation. Scheduled for emancipation in 1800. Emancipated by deed dated January 6, 1800; deed proved in Frederick County Court, January 6, 1800.”

[17] Daniel W. Bly, comp., “Records of Indentures and Guardianships in Shenandoah County, Virginia, 1772-1831” (extracted from the Minutes of the Circuit Court), online: http://www.vagenweb.org/shenandoah/bly_1822_1825.html (accessed 20 January 2021). Entry for 8 September 1823: “Overseer of Poor to bind Abraham, a boy of color to Henry Forrer to learn farming. He is 15 years old June 27, last.”

[18] June Purcell Guild, Black Laws of Virginia (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 1995, reprint of 1936 original), 100.

[19] Ebert, “A Window on the Valley,” 34–35.

[20] H. E. Comstock, The Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region (Winston-Salem, NC: Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1994), 377.

[21] Ibid.

[22] 1820 United States Census. Jesse Spencer was listed in 1820 as having one male free person of color under the age of fourteen, one male free person of color aged twenty-six to forty-four years, four female free persons of color under the age of fourteen years, and one free female person of color aged twenty-six to forty-four years.

[23] Joseph Martin, A New and Comprehensive Gazeteer of Virginia and the District of Columbia (Charlottesville, VA, J. Martin, 1835), 451; available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/loc.ark:/13960/t3nv9r141 (accessed 20 January 2021).

[24] 1840 United States Census. In his census record, John Hoffman’s name is written with the word “Potter” in parenthesis following his name. This is an unexpected occurrence as the occupations or trades of individuals were not usually recorded in the 1840 Census. Other influential neighbors of the Spencers in New Market were the Henkel family. The renowned Reverend Paul Henkel resided two lots from Jesse Spencer. Solomon Henkel, Rev. Henkel’s son, was a physician and pharmacist who studied medicine in Philadelphia and with other members of his family started a New Market printing business in the early 1800s. “Solomon Henkel to Thomas Jefferson, 5 July 1817,” Founders Online, National Archives, online: https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Solomon%20henkel&s=1111311111&sa=&r=1&sr= (accessed 20 January 2021); original source: J. Jefferson Looney, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series, Vol. 11, 19 January to 31 August 1817 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 2018), 504.

Solomon Henkel also ran a drugstore in New Market and within his day book for 1817 there are numerous entries for Jesse Spencer. Spencer was credited for manual labor, including cutting wood, washing, and hay making. Spencer’s debits include several entries for bleeding his wife, tinctures and herbs purchased for his wife, and also one entry that reads, “Jesse Spencer [debit] to Bleeding Self & David & Pills.” Solomon Henkel, “Day Book of Solomon Henkel: Begun and continued to be kept by him from the first Day of March in the Year of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ 1817,” pp. 27 and 79. Collection of the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. H. E. Comstock, 2019.24.1.

[25] Shenandoah County, Virginia, Deed Book JJ, 1838–1840, 5 May 1830, pp. 194-195, microfilm, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[26] Nancy R. Stewart, comp., “A List of Free Negroes with the District of James Allen, one of the Commissioners of Revenue for Shenandoah County for the year 1835” in African Americans in Shenandoah County, Virginia, Notebooks, Vol. II: Book B, manuscript, 2010, Shenandoah County Historical Society, Woodstock, VA.

[27] One of Abraham Spencer’s daughters’ names is also listed as “Sarena” or “Serena” in the 1860 United States Census, but her birth year would have been around 1852. Stewart, African Americans in Shenandoah County, Virginia, Notebooks, Vol. II: Book A, p. 29, 6 March 1837. Entry reads: “Overseer of the Poor to bind Sirene Spencer, a girl of color, to Joseph R. Sibert to learn spinning, cooking, and cleaning and to ascertain her age.” Further research on Joseph Sibert is warranted as his name also appeared on the records of Prince Henry for settling Henry’s estate when he died in the 1840s.

[28] Stewart, “1828 Shenandoah County Register of Free Colored” in African Americans in Shenandoah County, Virginia, Notebooks, Vol. II: Book A, p. 6. Entry reads: “September 8, 1829, registration #141 o Abraham Spencer, “a free negro”. Abraham Spencer would have been around 22 years in 1830.”

[29] Nancy R. Stewart, “How Did Shenandoah County Get into the Slavery Business?” p. 8, manuscript, Shenandoah County Historical Society, Woodstock, VA.

[30] Guild, Black Laws of Virginia, 108.

[31] Legislative Petitions, Frederick Co., VA, 12 February 1838, Hadley Library and Archives, Winchester, VA. Entry reads: “[citizens of Frederick County] regard the residence of the free black population among us as highly injurious & deprecate its increase as an intolerable burden… . The series of laws commencing with that of 1806 has been frustrated by the Legislature of our sister States prohibiting the admission of this class of population into their respective territories. Besides, the Acts alluded to refer only to those emancipated since 1806 except the Act of 1833, the defect of which is obvious, in the complicated action required by the County Courts.”

[32] Legislative Petitions, Frederick Co., VA, 12 December 1837, Hadley Library and Archives, Winchester, VA. Note: although this folder was marked for Frederick County it contains petitions from other areas including the quoted excerpt from Shenandoah County.

[33] Ted Maris-Wolf, Family Bonds: Free Blacks and Re-Enslavement Law in Antebellum Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2015), 43.

[34] Stickley Family Papers, 1795–1912, Loose Ephemera, MsslSt515 a304-321, section 21, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, VA. In 1840, Prince Henry was taxed for “2 free negroes” at $2.00 and taxed fifty-three cents for 2 lots in the town of Woodstock.” It is noteworthy that the settlement of the estate was done by Joseph Sibert, perhaps the same Joseph Sibert who Jesse Spencer and Sirene Spencer were bound to in the 1830s.

[35] The 1840 United States Census recorded a man named John Ford living at Lot 13. John Ford probably died between 1840 and 1850 and his wife Rachel Ford (possibly Jesse Spencer’s daughter) was recorded at the property in the 1850 Census, with Jesse Spencer (age 70) also living in the household. Rachel Ford sold New Market Lot 13 for non-payment of taxes in 1873. Jesse Spencer had married Rebecca Moore in 1839 (see Endnote 12).

[36] MacDonald, Free Blacks on the Personal Property Tax Lists of Winchester, 167, 207. The 1840 United States Census recorded a free African American named Abraham Spencer living in Page County, Virginia with one person in his household employed in manufactures and trade. Little scholarship has been published about pottery made in early Page County. This may or may not be a record for the potter Abraham Spencer, although he does not appear elsewhere in the 1840 census. In his seminal book on the pottery of the Shenandoah Valley region, H. E. Comstock noted that in 1870 a man named Daniel Coffman (possibly the same Daniel Coffman mentioned earlier in New Market) was working at a pottery in Luray, and that by that time the only recorded pottery in the area “was at Blosserville (Stonyman) in Luray District.” Comstock described the pottery as being rented by a merchant named David H. Henkel in 1870, but gives no information for a pottery operating in the 1840s when Abraham Spencer may have resided in Page County. Comstock, The Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region, 387, 311–314.

[37] The 1850 United States Census also recorded another Abraham Spencer in Frederick County, residing in Middletown. There is no evidence that this Abraham Spencer was a potter, but he was listed as living beside merchants, father and son, George Wright and John Wright.

[38] MacDonald, Free Blacks on the Personal Property Tax Lists of Winchester, 213. Benjamin Howard was recorded in 1851 as a potter and twenty-four years old (“List of Free Negroes in the County of Frederick,” 1851, Frederick County (Va.) Free Negro and Slave Records, 1795–1871, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA. The same document recorded Abraham (Abram) Spencer as a male, age sixty-three and a potter, along with his wife, Henny Spencer, age fifty-six and a “Cripple.”

[39 Stewart, “How Did Shenandoah County Get into the Slavery Business?” 8.

[40] MacDonald, Free Blacks on the Personal Property Tax Lists of Winchester, 167, 207. Note: Designations of these districts has not been fully deciphered.

[41] Ebert, “A Window on the Valley,” 36. Abraham Spencer appeared in the 1851 and 1853 tax lists so recorded.

[42] Stewart, African Americans in Shenandoah County, Virginia, Notebooks, Vol. II: Book A, p. 6.

[43] Comstock, The Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley Region, 435.

[44] Maria Graham Koontz Carr, My Recollection of Rocktown, Now Known as Harrisonburg, from 1817–1820 (Harrisonburg, VA: F. Stover, 1959), 35.

[45] A.H. Rice and John Baer Stoudt, The Shenandoah Pottery (Strasburg, VA: Shenandoah Publishing House, 1929), 62.

[46] See Kuettner, “…my friend David Jarboe…” for a discussion of free and enslaved potters in Alexandria incising their pots with only a single initial.

[47] Rice and Stoudt, The Shenandoah Pottery, 62.

[48] Death Certificate for Abraham (Abram) Spencer, 31 October 1873, Winchester, VA, “Virginia Deaths and Burials, 1853–1912, database, FamilySearch.org, online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XR91-7VH (accessed 20 January 2021). Spencer’s death certificate noted that his mother’s name was Mary and his father was Jesse Spencer. It also recorded his birth date as 1798.

[49] Clifton Johnson, Battleground Adventures: The Stories of Dwellers on the Scenes of Conflict in Some of the Most Notable Battles of the Civil War (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1915). 406.

[50] Ibid, 407. Rice and Stoudt also recorded remembrances of Abraham Spencer’s physique by Strasburg residents: “…some say he weighed two hundred pounds, others that he weighed at least three hundred pounds, while a few declare his weight was at least four hundred pounds.” Rice and Stoudt, The Shenandoah Pottery, 63.

[51] Ibid, 62.

[52] Day book of Brinker and Harris, merchants, Middletown, Frederick Co., 16 September 1867 (book not paginated), VA, Mss. MsV Ame9-MsV Ame10, Special Collections Research Center, SWEM Library, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA.

© 2020 Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts