The focus of this article is the 125 outstanding client accounts from 1839 to 1852 of Rockbridge County, Virginia, cabinetmaker Thomas G. Chittum. The client accounts are found in the 1855 Rockbridge County chancery court case John D. Camden vs. Thomas G. Chittum, Etc. The case has been digitized and may be accessed online through the Library of Virginia’s Chancery Records Index.[1] This article will analyze the client accounts to understand Chittum’s furniture production, look at his connection with other craftsmen, and provide a list of customers. Analysis of the accounts will add to the relatively few published resources and contextualize the cabinetmaking business in this part of the Valley of Virginia (Figures 1 and 2).[2]

Early Life

Before examining the client accounts it is necessary to understand Chittum’s career and the socioeconomic environment in which he worked. Thomas G. Chittum was born in 1805 in Goochland County, Virginia, to William Chittum and his wife Nafanar Grubb Chittum.[3] His parents were married 23 October 1791 in Goochland County. The bride’s father, Daniel Grubb, gave consent for her, as she was underage.[4] By 1815, the family lived in Rockbridge County, Virginia.[5] In 1820, William Chittum, who owned no land, mortgaged his personal property. Among the items listed was one set of carpenter’s tools, which may indicate his occupation.[6] After 1820, there is no further record of William Chittum in Rockbridge County.

It is possible that Thomas G. Chittum’s maternal grandfather, Daniel Grubb, was also a carpenter. In his will, he called himself a farmer.[7] However, items found in Daniel Grubb’s inventory—such as hand saws, planes, chisels, augurs, and a set of turning tools—suggest Daniel Grubb did more than farming.[8] Moreover, in the Goochland County chancery case of Gideon Moss vs. Executors of John Moss, Daniel Grubb states in his deposition of 13 May 1791 that he had “saw plank to lay a floor”[9] for Gideon Moss, which proves his woodworking occupation. Thus, Thomas G. Chittum was the third member of his family to be involved in woodworking.

The Valley of Virginia

The Valley of Virginia differed from that part of the state east of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Migration to the Valley, which began in the 1730s, was made up primarily by settlers from eastern Pennsylvania traveling south along the Great Wagon Road. The settlers were a diverse group both ethnically and in religious affiliation. This melting pot of Quakers, Scots-Irish Presbyterians, and German speaking members of the Lutheran, German Reformed, United Brethren, Mennonite, and Church of the Brethren congregations more closely resembled Piedmont North Carolina than eastern Virginia. While the dominant ethnic group in Rockbridge County were Scots-Irish Presbyterians, there were also German speaking settlers. There seems to be a blending of the two cultures in the county.[10] These settlers brought with them the building styles, craftsmanship, artistry, and farming techniques that they had known in Pennsylvania.

In the Valley of Virginia, three factors drove the development of towns. The first factor was where the Great Wagon Road crossed routes that went east through the Blue Ridge Mountains. Another reason was a combination of being near water courses and trade routes. Becoming the seat for the county court was the third factor. Lexington in Rockbridge County was both the county seat and a location where the wagon road and routes that went east through the Blue Ridge Mountains crossed.[11]

The socioeconomic life of Rockbridge County was far different than that of Goochland County and eastern Virginia. The economy of the Valley of Virginia was based on the raising of wheat. The social system was more middle class than eastern Virginia and resembled that of Pennsylvania. Rockbridge and the counties of the upper valley were less developed than the counties of the lower valley and had commercial relationships to Richmond.[12] The greatest distinction between the Valley of Virginia and eastern Pennsylvania was slavery, be it enslaving individuals or hiring enslaved persons.[13]

Lexington Cabinetmaker

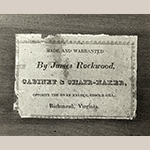

The first record of Thomas G. Chittum as a cabinetmaker appeared in a notice of the 2 February 1838 issue of the Lexington Gazette, which stated that cabinetmaker James Rockwood hired Chittum to manage his shop.[14] The 1850 census listed Rockwood as being born in 1797 in Massachusetts. By 1820, he resided in Richmond, Virginia.[15] He was in Lexington by at least 1826.[16] In the 1840 census, Rockwood was listed in Botetourt County, which is the county south of Rockbridge. He appeared on the 1850 census for Cooper County, Missouri, and his occupation was listed as farmer at that time. A labeled card table (Figures 3 and 4) was made while Rockwood was working in Richmond.

In 1839, James Rockwood was in debt and executed two deeds of mortgage. In the first deed, to satisfy his creditors he mortgaged the contents of his blacksmith shop and his cabinetmaking shop.[17] The second deed of mortgage listed specific amounts owed to two creditors, but beside the names of the other six creditors instead of a specific amount owed was the phrase, “in a sum not known.” Because Jacob Ruff, one of the creditors, was assigned the task of resolving the financial situation, Rockwood mortgaged the following two important items:

one ledger bound in paper binding (and more particularly described as half binding) which ledger, commences in August 1826, and contains the accounts of the said Rockwoods cabinet making business, which said ledger, together with all accounts & claims contained in it.—Also one other ledger, bound in leather, commencing on February 1837, and contains the accounts of the said Rockwoods blacksmith shop, and other accounts & debts due the said Rockwood, which last named ledger with all accounts & claims contained and charged in it.[18]

The only way for Jacob Ruff to resolve Rockwood’s financial problems was to follow the money, and that could only be achieved through the ledgers and accounts. Sadly, the way to understand Thomas G. Chittum’s cabinetmaking business would also come through following his accounts.

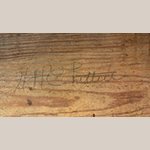

Chittum’s desire to be master of his own shop may have been hastened on by Rockwood’s difficulties. In any case, their business connections did not last long, and Chittum advertised in 5 October 1838 issue of the Lexington Gazette that his new business location was, “a shop lately occupied by Mr. Dorsey one door below Franklin Hall.”[19] The following year, Chittum purchased a lot in Lexington described as being between the lots of Dr. John W. Paine and Henry Norgrove, fronting Main Street and extending to Jefferson Street.[20] The 18 May 1839 issue of the Lexington Gazette provided further description of the location as one door west of Dr. Paine’s and opposite the saddlery shop of Mr. John Carr.[21] The notice advertised furniture “made in the neatest manner possible and coffins, which could be sent to any to any part of the county.”[22] A table, illustrated in Figure 5, is attributed to Thomas Chittum based its provenance, in particular the signature of his grandson, Hugh Hugo Chittum (Figure 6).

Chittum stated in the 25 May 1843 issue of the Lexington Gazette that he could offer the public turning of all kinds.[23] The turned legs on the table in Fig. 5 reflect this capacity. In 1850, Chittum expanded his furniture offerings and advertised that he had a large assortment of chairs for sale.[24] Given that turning and chairmaking are specialized trades that differ from cabinetmaking, the last two notices raise the question, which will be discussed later in the section titled “Furniture Repairs,” if Chittum was subcontracting turning and chairmaking to other craftsmen.

John D. Camden vs. Thomas G. Chittum, Etc.

In her book Buying into the World of Goods: Early Consumers in Back Country Virginia, Ann Smart Martin emphasizes that anyone doing business needed to know bookkeeping to understand their specific financial status. This double entry system of debits and credits required various interconnected volumes that had to be maintained on a regular basis.[25] In Lexington, the cabinetmaker Thomas G. Chittum, a carpenter named William Gibson, and John D. Camden, a sawmill operator, all lacked the ability to keep records of their business transactions and thus found themselves entangled in litigation in the Rockbridge County Circuit Superior Court of Law and Chancery.

In 1842, Chittum delivered furniture valued at $75.75 to the sawmill operator John Camden. The furniture consisted of the following items: a bureau, two bedsteads, a safe, and some chairs. Problems over payment for the furniture soon arose. Camden claimed that the carpenter William Gibson was indebted to him and ordered the furniture from Chittum to pay off the debt. Camden claimed that Chittum was indebted to Gibson for a contract to supply Chittum with plank and the furniture would satisfy all debts involving the three men. In response, Chittum stated the furniture order was at Camden’s request and that he was not indebted to Gibson.

Six years later, in 1848, Chittum had still not been paid for the furniture and had Camden sign a bond that obligated him to pay for the furniture. Chittum was given a judgment for an execution—an order to seize and sell—on Camden’s property in 1851. Camden responded the following year by bringing suit in chancery against Chittum and Gibson with a bill of complaint dated 7 June 1852. In his complaint to the court, Camden requested that Chittum and Gibson be required to settle their accounts and show who owed what to whom.

Because the case was too complicated to be decided by written law, it was heard in chancery court. Chancery cases were complicated law cases that had to be decided by fairness rather than written law. The final disposition of such cases were decided by the court and not a jury. The three main parts of a chancery case are the plaintiff’s bill of complaint, the defendant’s answer, and the court’s decree, although other documents may also be included, such as accounts and depositions.

In the depositions for this case, Gibson was questioned if he had asked Chittum for an account of the furniture provided to Camden. Gibson responded that he had not asked specifically for a bill for the furniture furnished to Camden, but requested that Chittum make a settlement of all accounts between them. Chittum responded that, “he was no s[c]holler himself for his wife kept his books & they were badly kept, but he was a going to some one to make out his accts.”[26]

Chittum’s statement during his deposition is significant because it establishes that he was illiterate (barely able to write his name”) and he relied on the math skills of his wife, Frances Sarah Turner Chittum, to keep his shop’s books.[27] It is difficult to determine whether it was rare in the first half of the nineteenth century for wives to keep ledgers for their cabinetmaking husbands. Very little if any research has been done about gender roles and bookkeeping in the shops of early American mechanics. That said, scholars of business history have written that before the 1870s the “relations between employer and employee were quite personal” but that “middle-class men generally filled bookkeeping positions.”[28] Thus, Frances Chittum’s keeping of her husband’s books could be quite significant and worthy of further inquiry by students of early American cabinetmakers.

Returning Chittum’s court case, matters became more complicated when the plaintiff John Camden died before the case was settled and the sheriff of Rockbridge County, J. A. M. Lusk, as administrator of Camden’s estate, took his place as the plaintiff. In the end, on 17 September 1855, the court issued its decree and required that Chittum pay Camden’s court costs.

Goods

The lack of bookkeeping skills that caused Chittum’s legal problems resulted in the inclusion of 125 accounts in the chancery case file. These accounts allow the researcher of southern decorative arts an opportunity to better understand furniture forms produced in the upper part of the Valley of Virginia. The outstanding accounts from the chancery case fall into the categories of goods and services. Goods included the following categories: 1) furniture produced; 2) coffins and funerals; and 3) other woodworking products. Services are interpreted to mean repairs. The total amount of revenue came to $2,428.05:

• Furniture: $1,481.96 (61%)

• Coffins and Funerals: $492.75 (20%)

• Miscellaneous woodworking: $385.73 (16%)

• Repairs: $67.61 (3%)

These accounts provide insight into Chittum’s shop, even if they cannot provide a completely accurate picture of his business. It is important to recognize that these records document only outstanding accounts and are not a comprehensive account book. That said, the client accounts represent a rare glimpse into the production of a Rockbridge County cabinetmaker’s shop in near the middle of the nineteenth century.

With accounts for eighty bedsteads and fifty-four coffins, as well as replacing knobs for a bureau and making newel posts and carriage hubs, it is evident that Chittum was steadily producing a wide variety of goods and services for the citizens of Lexington and Rockbridge County. In 1902 Chittum’s service as a cabinetmaker for the community was still fresh in the memory of local residents. From February through March of 1902 the Rockbridge County News published a series of articles by William Alexander Ruff entitled, “Reminiscences of Lexington 65 and 70 Years Ago.” The author went block by block describing the inhabitants. Of Thomas G. Chittum, he wrote the following: “Across the alley and above lived Thomas Chittum, who was a cabinetmaker by trade and did a considerable business.”[29]

Furniture Forms

Bedsteads

From 1839 to 1851, the client accounts record eighty of the bedsteads produced by the Chittum shop. Twenty-four of the bedsteads were described as “acorn bedsteads” and cost $9.00 apiece. The term “acorn” probably refers to the turning at the top of the bedpost. For a comparison, the bedstead in Figure 7 illustrates a North Carolina bedstead with this type of turning. Because the table in Fig. 5 is the only known surviving furniture form attributed to Chittum’s shop, all of the illustrated furniture examples that follow are presented for comparison only and are not associated with Chittum or his shop.

Twenty bedsteads were described as “common bedsteads” and ranged in price from $2.00 to $6.00. Sixteen bedsteads, one of which was made of walnut, were listed simply as “bedsteads” and ranged in price from $3.00 to $18.00. Nine “fine bedsteads “were included with the cost ranging from $8.00 to $18.00. One of the “fine bedsteads” was made of walnut, and another was described as a high post bedstead. Six trundle bedsteads, one of which was painted, were made with cost ranging between $3.00 and $5.00. Two high post bedsteads were listed for $12.00 each. There was an entry for one French bedstead for $20.00, one curtain bedstead at $15.00, and a single bedstead for $4.00.

Breakfast Tables

From 1841 to 1850, the accounts recorded Chittum making nine breakfast tables or Pembroke tables for an average price of $5.00 each.

Bureaus (Chests of Drawers)

Nine bureaus, or chests of drawers, were recorded being made between 1840 and 1844. The accounts had two listings for “a bureau,” one for $14.00 and one for $18.00. The three cherry bureaus listed cost $25.00 apiece. Three walnut bureaus were listed at $18.00 each. The most expensive bureau was a “fine walnut bureau” for $30.00.

Chests

Chittum sold a chest in 1845 for $4.00.

Benches

Three benches were recorded as being made by Chittum, one for $1.00, a second for $0.375, and the third for $5.00.

Bookcases

Two bookcases were sold in 1841 for $8.00 each. In 1845, another bookcase sold for $6.00.

Candlestands

From 1842 to 1846, there were only three listings for candlestands with an average cost $4.00. For an example of a Rockbridge County, Virginia, candlestand, see Figure 8.

Chairs

From 1843 to 1852, there were seven entries for the sale of chairs. Three rocking chairs were sold; one was described as large, and another was described as having a cane seat. There were two entries for sets of chairs, with one set having cane seats.

Several of these entries for chairs show that Thomas Chittum had interactions with other artisans. In 1842, he sold various items including plank for rockers to Lexington chairmaker Enoch Bogus, who paid part of his bill with a rocking chair.[30] In 1846, Chittum sold Lexington chairmaker Samuel R. Smith “chair stuff,” which was material used for stuffing an upholstered chair.[31] The account for Lexington cabinetmaker Matthew S. Kahle, shows work done for him by Chittum.[32] The account with Kahle also shows the following purchases:

1852 to Matthew S. Kahle

May to ½ doz split bottom chairs 7.50

To cash 5.00 5.00

March 20th to 38 of inch and ¼ plank .76

To piece of poplar .50

To 2 dozen chairs

To be paid in cabinet work at twenty dollars and also stuff

for chairs at sixteen dollars

Because the wording of this interaction between Chittum and Kahle is sufficiently vague and there is a lack of a clearly marked sections for debits and credits, it is not clear who is the seller and who is the purchaser of the chairs. While cabinetmaking and chairmaking are usually two different crafts, Chittum’s 1850 advertisement for the sale of chairs, customer accounts for the purchase of chairs, and the fact that Chittum’s inventory lists chair cane, chair rungs, and hair cloth would seem to indicate that he was making chairs or at the very least retailing chairs.[33]

Coffins (and Funerals)

The accounts listed fifty-four coffins, of which six were described as “covered coffins,” one was listed as a “covered coffin and box,” and one was listed as a “covered coffin and case.” The term “covered coffin” refers to a coffin with a piece of cloth covering it.[34] The terms “case” and “box” may both refer to what is now called a vault in which a coffin is placed given that in the ledger of Augusta County cabinetmaker William Benjamin Alexander, who was Chittum’s contemporary, there are entries for a “coffin and case” and a “coffin and a vault.”[35]

A typical funeral entry, such as the account of a Mr. Irvin, lists simply a “coffin and taking out the same.” While most entries for coffins are not detailed, the account for Jacob Clyce was particularly specific:

Covered coffin for wife $20.00

Trimmings $5.00

Making a case $5.00

[Total] $30.00

Matthew Kahle’s account with Chittum listed the following two funeral costs: The entry for 12 May 1840 was for “taking out coffin 3.00,” which meant transporting a coffin to the home of the deceased. This could have been handled with a wagon. The second entry, for 8 November 1840, was for “taking corpse to timberridge 2.00,” which meant transporting the deceased to the country for burial. In this case, a wagon or hearse may have been used. The assumption is that for whatever reason Kahle did not have a means of transportation on those days.

Thomas G. Chittum also made coffins for African Americans. Three coffins were made for Black children, and one coffin was made for a Black woman. Another account was for Jordan and Jordan, which was a partnership that formed in 1847 between brothers Samuel Francis Jordan and Benjamin J. Jordan. The Jordans established the Buena Vista Iron Furnace, which was located on the South River a few miles east of Lexington.[36] They purchased a coffin for a “hired servant.” According to the account, “His height 6 feet 4 inches width 19 inches.” Enslaved individuals and those hired out by their enslavers formed the fundamental workforce for the iron manufacturing industry in Virginia and elsewhere in the American South. For example, in 1771 the state of Virginia hired enslaved people to work at the Public Foundry at Westham near Richmond.[37] On 7 November 1777, David Ross, owner of the Oxford Iron Works near Lynchburg, placed a notice in the Virginia Gazette for the hire of enslaved men. In Chittum’s home county of Rockbridge County, the Buffalo Forge had over a hundred hired enslaved workers.[38]

The exception to individual accounts for coffins was two accounts for the Overseers of the Poor. In colonial Virginia, the Anglican vestry provided for the impoverished. After the American Revolution, this responsibility was taken over by the county government organization known as the Overseers of the Poor. By Chittum’s time, the destitute lived in the county poor houses. The Overseers of the Poor were responsible for persons who died in their care, and therefore paid to have coffins made for the deceased, as well as for burials.

Cradles

From 1833 to 1847, the records show Chittum made at least six cradles, four of which were of walnut. The costs ranged from $3.00 to $4.00.

Cribs

Chittum sold a crib in 1844 and another in 1846. Both items cost $5.00.

Cupboards

Nine cupboards were made between 1840 and 1848, with a price range between $12.00 and $15.00. There were three listings for “a cupboard,” one for $12.00, one for $16.00, and one for $18.00. There were two listings for “walnut cupboards,” one for $14.00, and one for $18.00. The most expensive cupboards were two cherry cupboards, both of which cost $25.00. A listing for making the lower part of a cupboard for $5.00 suggests a cupboard with two separate parts.

Dressers (Kitchen)

There was an 1845 account for “1 dresser for kitchen,” with a price of $3.60. This furniture form was probably a cupboard with an open top for the placement of dishes.[39] Figure 9 illustrates an example from Augusta County, Virginia.

Fire Screens

In 1840, one fire screen sold for $0.75.

Frames (Looking Glass)

In 1842, one looking glass frame was sold for $4.00.

Frames (Picture)

From 1840 to 1846, Chittum made twenty-two picture frames.

Hatracks

In 1847, Chittum made one hat rack for $1.00.

Presses

There was an 1840 account for a cherry china press for $25.00, and an 1843 account for a press sold for $12.00.

Safes (Food/Storage)

From 1831 to 1845 there were four accounts for safes for the storage of food and other items. The costs ranged from $7.00 to $12.00. Safes in the Valley featured punched-tin panels for air circulation and keeping insects and rodents away from the food and other kitchen or household items stored in the safes.[40] Figure 10 illustrates an example with punched-tin panels made in Botetourt County or Roanoke County.

Sideboards

The only account for a sideboard was for one that cost $15.00 in 1845.

Stools

Only two stools were recorded in Chittum’s outstanding client accounts although his shop almost certainly produced more. Both recorded stools cost $1.00.

Tables (General)

From 1832 to 1847, there were nine listings for a “table” with costs ranging from $2.50 to $8.00. One of the tables was described as square in shape.

The account for Robert Gilmore in the 1840s listed two bedsteads and a dining table made by Chittum. While Gilmore paid off his bill primarily in produce, such as a bushel of apples or damsons, payment was also made by 250 table legs for $12.50, 240 table legs for $12.00, and five locust posts for $0.80. See Fig. 5 for an example of turned table legs attributed to Chittum’s shop. The 1850 Rockbridge County Census lists a teacher Robert Gilmore, age 70, who was born in Ireland. This could be a candidate for the maker of the table legs, or it could refer to another Robert Gilmore who had died or left Rockbridge County by 1850. This brings up the question were the table legs tapered or turned? If turned, Robert Gilmore could have been a turner employed by Thomas G. Chittum.

Tables (Dining)

Chittum made ten dining tables from 1841 to 1847. Nine of the dining tables sold for $9.00, and one described as a small dining table was priced at $7.00.

Tables (Little)

Four tables described as “little tables” were sold for $2.00 to $3.00 from 1841 to 1846.

Tables (Writing)

A writing table was sold in 1839 for $7.00, and a second one was sold in 1843 for $4.00.

Wardrobes

Two wardrobes were sold in the 1840s, one for $12.00 and another for $17.00.

Washstands

Fourteen washstands were sold between 1839 and 1847. One was described as being made of cherry, and a second one was made of walnut. The costs varied from $2.50 to $10.00. Illustrated in Figure 11 is a walnut with yellow pine example from the Shenandoah Valley that dates to the period Chittum’s shop was actively producing similar washstands.

Work Stands

Three work stands or tables for ladies’ sewing were produced between 1842 and 1846, two of which were made of cherry. The cost ranged between $4.00 to $5.00. A Wythe County, Virginia, work stand or sewing table made by James Frederick Seagle is illustrated in Figures 12 and 13. While this is a compartmentalized work stand, one or two drawer tables were also used as work stands.

Miscellaneous Woodworking

Thomas G. Chittum did various woodworking jobs for Lexington craftsmen. Hatmaker John McConn paid him for turning ten hat blocks. Chittum turned four carriage hubs for cabinetmaker Matthew S. Kahle. The account of gunsmith W. George Cockrell had numerous listings for making gun stocks. Illustrated in Figures 14 and 15 is an example of a Rockbridge County, Virginia, rifle made by William Zollman. For boot- and shoemaker J. L. Deaver, Chittum made two crimping boards, which were templates used in cutting leather. In May of 1848, iron manufacturer B. J. Jordan placed the following order with Chittum: “make the pattern I send it by the bearer. the Hole in the center to be strong 1¼ inch. Make both sides like the best side of the one sent.”

The account for coppersmith Thomas M. Wade showed a charge for making one hydrant cap and two boxes for the [Virginia Military] Institute hydrant, as well as many other listings for hydrants, boxes for hydrants, plugs for hydrants, and bucket handles. This work was explained in an article written by his son, Benjamin F. Wade, and published in the 27 February 1936 issue of the Rockbridge County News:

About this time the whole town was dependent for water upon two springs, one on Randolph street and the other on Jefferson street. The one on Jefferson Street is now unknown, but every student coming up town passes over or very near it, as the street has had a great fill. One servant was required to supply every family with water. Then as a matter of economy it was determined to get from Mr. A. T. Barclay the right of way through his land to pipe the water to the town from Brushy hills. The streets were trenched for months for the pipes, and made mothers anxious, as they were several feet deep and often filled with waters from the rains. In fact this writer, was a victim of the above said anxiety. The hydrants were placed along the streets and every family had an iron key to open them. The thirsty traveler must get a key to get water. Such was the basis for your splendid system of water supply. It was a comfort to rich and poor.[41]

There were numerous listings for other building or architectural items produced by Chittum’s shop. For G. A. Baker, there was a charge for turning knobs for a gate. Other turning work included three newel posts for Joseph Steel and eight porch columns for John C. Laird. Accounts for innkeeper William Jordan included putting up washstands in cabins and building a bathhouse.

For Madison Pettigrew, Thomas G. Chittum turned a coconut shell, which was probably for the bowl of a water dipper. Other items for his customers included an apple butter stirrer, a fly brush handle, and a squirrel cage. For iron manufacturer Samuel F. Jordan, there was an entry for “wooding parr of skates for son.” There were also listings for “turning mallets”; making a large number of bucket handles; making and altering brick molds; producing four washing machines at $1.50 each in 1842; and in 1847 making “1 show case” sold for $4.50 to Hugh Barclay, a Lexington merchant.

Furniture Repairs

Repairs are a constant in life. Typical entries for furniture repair included items such as varnishing a bedstead, a set of bureau knobs, and repairing a wardrobe. Comparing furniture forms produced and furniture forms repaired provides interesting information. Chittum made nine bureaus and repaired nine bureaus. Three workstands were made and three workstands were repaired. Chittum made two wardrobes and repaired two wardrobes. Nine cupboards/presses were made, and four were repaired. No desks were made, but one desk was repaired. Thus, furniture repairs were an essential part of Chittum’s business—and probably most cabinetmakers—and provided a steady stream of income.

The two entries for a Mr. Powers for turning legs for a washstand and turning posts for a common bedstead show that Thomas G. Chittum had a lathe. Again, see Fig. 5 for a table with turned legs attributed to Chittum’s shop. The question is, did Chittum do the turning, or was the work contracted out to a turner? The relationship of a turner working with a cabinetmaker such as Chittum—whether employed in the shop or contracted out—is difficult to establish due to the substantial number of furniture forms and other items turned from wood that require a lathe and a skilled turner. While Chittum may have done the turning work himself, there is also evidence that there was a separation of trades in Lexington. As previously mentioned, the account of Robert Gilmore reveals that he paid part of his bill to Chittum with 250 table legs for $12.50 and 240 table legs for $12.00, implying that—if the table legs were turned—Gilmore may have been a turner. One of Chittum’s other clients, an F. Kurtz, was identified as a turner in the accounts. While there is a strong connection between the trades of chairmaking and turning, it is worth noting that the Lexington chairmaker Samuel R. Smith in 1842 paid Joseph Bell for turning and in 1844 paid Jacob Parent for turning.[42] The chairmaker Smith seems to have required the services of contracted turners even though as a chairmaker Smith most likely was adept at the lathe himself. Although these facts do not absolutely prove that Chittum did not operate a lathe, it does indicate a diversification of trades and raise the possibility of a contracted turner working in his shop.

Clients

By analyzing the 1850 federal census and annual personal property tax records, it is evident that Thomas G. Chittum’s clients spanned the range from the wealthy to those moderately well off to those of more limited means. Similar results were recorded in this author’s 2004 article on the analysis of the account book of Lynchburg cabinetmaker Sampson Diuguid.[43] Competition from local and northern producers of furniture required southern cabinetmakers such as Chittum to provide goods and services to anyone who could pay them.

The 1850 federal census and personal property tax records were used to assess the relative wealth and economic status of Thomas Chittum’s clients. While the value of real estate reported in the census and the number of enslaved individuals taxed cannot provide a complete portrayal of the wealth of Chittum’s clients, taken together, they nevertheless offer a generalized overview of their economic status.[44] Appendix A contains a complete list of Thomas G. Chittum’s clients and the value of their real estate from the 1850 census (if any was reported). Appendix B consists of those clients who were enslavers and the number and age ranges of individuals for whom they were taxed in 1850.

Examples of the top economic tier of Chittum’s clients include iron manufacturer Samuel F. Jordan, farmer Joseph Steel, and merchant Hugh Barclay. Jordan had real estate valued at $24,000.00 and was taxed for eleven enslaved people above 16 years of age. Steel had real estate valued at $17,000.00 and was taxed for four enslaved people above 12 years and eight enslaved people above 16 years. Barclay had real estate valued at $18,000.00 and was taxed for two enslaved people above 12 years.

Examples from the next economic group are farmer John Kerr and coppersmith Thomas M. Wade. Kerr’s real estate was valued at $4,000.00, and he was taxed for four enslaved people above 16 years of age. Thomas M. Wade had real estate valued at $4,000.00 and was taxed for three enslaved people above 16 years of age. This middle group is an example of clients that while not the elite were solidly well off.

Examples of the third group, which consists of craftsmen, have a wider range of economic resources and include blacksmith Joshua Parks, carpenter James Matheny, saddlers George W. Adams and Alexander McCown, cabinetmaker Matthew Kahle, and turner F. Kurtz. Joshua Parks had real estate valued at $1,500.00 and no taxable enslaved persons. James Matheny had real estate valued at $1,800.00 and was taxed for one enslaved person above 12 years. George W. Adams had real estate valued at $1,200.00 and was taxed for two enslaved people above 16 years of age. Matthew Kahle had real estate valued at $800.00 and was taxed for one enslaved person above 16 years of age. Alexander McCown and F. Kurtz had no real estate and no taxable enslaved persons.

Multiple individuals with the same name pose questions about the identity of Chittum’s client named James Harper, who may be the only African American client mentioned in the accounts. In 1841, Thomas G. Chittum purchased plank worth $7.44 from a James Harper, who was paid with a bedstead, scantling, and one lot of plank. The remainder was to be paid in a dollar’s worth of work. The only James Harper in the 1840 Rockbridge census is listed as white; however, in 1835 a James Harper, aged 33, was registered in the Rockbridge County “Free Negro Register.”[45] There is no listing for a free Black named James Harper in the Rockbridge County personal property tax for the years 1841 to 1842.[46] The 1850 Rockbridge census lists a James Harper who was a “mulatto” carpenter aged 49, and the 1860 Rockbridge census lists a free Black carpenter James H. Harper, aged 56. This James Harper’s age and trade as a carpenter make him the most likely candidate for the James Harper that Chittum purchased plank from in 1841.

Conclusion

Litigation between Thomas G. Chittum and John D. Camden began in 1851 when Chittum received a judgment for an execution on Camden’s property. Camden, feeling the judgment was not fair, had the right to counter the judgment with a case in chancery court, which he did in 1852.[47] While a chancery case may contain numerous accounts and other items, the 125 outstanding accounts for a cabinetmaker make Camden vs. Chittum a particularly rare find for the researcher of the southern decorative arts.

Chittum’s client accounts provide a window into the operation of a cabinetmaking shop during the mid-nineteenth century in Rockbridge County and the surrounding region. They reveal a considerable amount of business being done through Chittum’s shop and attest to a wide variety of furniture forms and miscellaneous items produced for the inhabitants of Rockbridge County. From cradles to graves (coffins), Chittum labored long and hard to produce items of use and beauty for his customers. As important are the records that bring to light his interactions with other artisans in the area.

In Chittum’s deed of mortgage to satisfy debts, dated 1852 and recorded in 1855, he put up his home as collateral.[48] This record was a harbinger of more financial troubles to come. Chittum died in June 1857 and his estate settlement presents a dire economic situation.[49] His debts were greater than his assets, as the entry “property claimed by the widow under the poor law” makes this point vividly clear.[50]

In the end, Thomas G. Chittum’s labors to meet the needs of Rockbridge citizens were not rewarded with economic security. The life of the southern cabinetmakers was not an easy one in the middle of the nineteenth century. They had to contend with local and northern wares and the vicissitudes of the economy. The estate records for cabinetmaker Willis Cowling of Richmond show financial problems.[51] As previously mentioned, James Rockwood left Virginia for Missouri to take up farming. If there is a silver lining in Thomas G. Chittum’s struggles—business or personal—it is the chancery case with 125 client accounts that allows researchers today to better understand the cabinetmaking business of this region of the Valley of Virginia in the 1840s and 1850s.

Christian Kolbe is an emeritus Archives Reference Services Coordinator at The Library of Virginia in Richmond. He can be contacted at [email protected]. He is much indebted to Ms. Cara Griggs for her editorial expertise.

APPENDIX A: Clients of Thomas G. Chittum

After the name of each client, there are the image numbers for the account from the John D. Camden vs. Thomas G. Chittum, Etc. chancery suit. When possible, the 1850 Rockbridge County census was used to identify the occupation of the client. In some cases the goods and services purchased from Chittum further documented the occupation. Value of real estate is noted when a client could be identified in the 1850 census.

|

Adams, Geo. W., 75-76, saddler, $1,200.00 |

|

Anderson & Parker, 185-186 |

|

Armentrout, Mr., 412-413 |

|

Baker, [George B.], 67-68, tailor, $6,700.00 |

|

Baldwin, C[ornelius], 392-393, lawyer, $2,000.00 |

|

Barclay, A. T., 375-376 |

|

Barclay, Hugh, 403-404, merchant, $18,000.00 |

|

Barclay, T., 379-380 |

|

Bare, Mrs. [Susan], 384-385, 444-445 |

|

Bear, Jacob, 63-64, silversmith |

|

Bowlen, Thomas, 388-389, blacksmith, $3,000.00 |

|

Bobbitt, Milton, 373-374, carpenter |

|

Buck, David, 394-395 |

|

Bogus, Enoch, 448-449, chairmaker |

|

Camden, Benjamin, 367-368, farmer |

|

Caruthers, E. G., 371-372 |

|

Caruthers, J. F. & E. G., 455-457 |

|

Caruthers, Wm. H., 365-366, farmer, $34,000.00 |

|

Charlton, Seburn, 65-66, painter, $1,000.00 |

|

Clark, Daniel, 369-370 |

|

Clyce, Jacob, 356-357, 442-443, carpenter |

|

Cockrell, W. George, 363-364, gunsmith |

|

Conner, Fitzallen, 361-362, carpenter |

|

Day, Wm., 341-342, Manager |

|

Deaver, J. L., 354-355, boot and shoe maker, $700.00 |

|

Douglass, Wm., 339-340, farmer |

|

Dunlap, Madison, 349-350, farmer, $13,000.00 |

|

Echols, Edward, 57-58, farmer |

|

Elison, Mr., 59-60 |

|

Estill, H. M., 347-348, physician, $5,000.00 |

|

Figgat, John T., 331-332, saddler, $3,000.00 |

|

Fisher, Martin, 335-336 |

|

Fix, Mr., 333-334 |

|

Graham, [Archd.], 61-62, physician, $10,000.00 |

|

Gibson, David A., 321-322, farmer, $5,000.00 |

|

Gillock, [Samuel], 327-328, printer, $850.00 |

|

Gilmore, Mr., 429-430 |

|

Gilmore, Robert, 323-324 |

|

Gilmore, Wm., 433-434 |

|

Gilmore, William C., 417, 427, 431-432, farmer, $6,000.00 |

|

Glasgow, R[obert], 329-330, farmer |

|

Gold, James, 318-319, farmer, $14,000.00 |

|

Gregory, Henry, 246-247 |

|

H[a]ll, John, 313-314 |

|

Hamilton, John G., 305-306, farmer, $6,000.00 |

|

Hamilton, Samuel, 309-310, wheelwright |

|

Harper, James, 315-316, carpenter |

|

Henry, Williamson, 307-308 |

|

Hull, Philip, 311-312 |

|

Hutcheson, Mrs., 55-56 |

|

Irvin, Mr., 303-304 |

|

Jordan & Jordan, 286 |

|

Jordan, B. J., 284-285, 288, iron manufacturer, $5,000.00 |

|

Jordan, Dr. James, 297-298, |

|

Jordan, Samuel F., 79-80, iron manufacturer, $24,000.00 |

|

Jordan, Wm., 291-292, inn keeper, $10,000.00 |

|

Johnston, Alex., 293-294, farmer, $2,000.00 |

|

Johnston, Thos., 299-300 |

|

Johnston, Saml., 301-302, overseer, $2,000.00 |

|

Kahle, Matthew, 282, 436-438, cabinetmaker, $800.00 |

|

Keffer, Abram, 275-276 |

|

Kennear, Herdin, 273-274 |

|

Kerr, John, 53-54, farmer, $4,000.00 |

|

Kinnear, Joseph, 271-272 |

|

Kurtz, F., 267-268, turner |

|

Lecky, Thomas, 260-261, farmer |

|

Laird, John C., 256-257, farmer, $1,800.00 |

|

Laughlin, Samuel, tailor |

|

Lawson, John, Estate of, 242-243 |

|

Lawson, Wm., 232-233 |

|

Letcher, Wm. H., 228-229, 230-231, carpenter, $7,000.00 |

|

Lewis, Wm. C., 262-263, Commissioner, $6,000.00 |

|

Lindsay, Mr., 250-251 |

|

Logan, Robert C., 244-245, 254-255, farmer |

|

Lowery, Mr., 258-259 |

|

McClung, James, 459-460, farmer, $3,000.00 |

|

McClure, Moses, Estate of, 465-466 |

|

McConn, 85-86, hatter, $700.00 |

|

McCoppen, Mr., 209-210, |

|

McCorkle, Benjamin, 220-221, farmer, $1,500.00 |

|

McCo[r]ckle, Saml., 207-208, $7,000.00 |

|

McCown, Alexr., 51-52, saddler |

|

McDowell, Robt., 343-344, farmer, $10,500.00 |

|

McKee, J. T., 224, Farmer, $8,000.00 |

|

McKee, John, 214-215 |

|

McWilson, H. J. & Thomas, 97-98, |

|

Matheny, James, 225-227, carpenter, $1,800.00 |

|

Middleton, John, 77-78, blacksmith, $7,750.00 |

|

Moor, James C. C., 216-217, farmer, $12,000.00 |

|

Moor, David E., 222-223, lawyer, $10,000.00 |

|

Moor, Wm., 205-206 |

|

Morrison, Wm., 212-213, farmer, $4,650.00 |

|

Overseers of the Poor, 40-41, 269-270 |

|

Parker, Mr., 183-184 |

|

Parks, Joshua, 81-82, blacksmith, $1,500.00 |

|

Paxton, Alex., 189-190, farmer, $5,500.00 |

|

Pettigrew, J. M., 129, confectioner |

|

Pettigrew, Madison, 49-50 |

|

Philips & Sydnor [also identified as “Wm. Sydnor’s Act.”], 71-72 |

|

Plank Road Company, 188 |

|

Powers, Mr., 179 |

|

Ruff, John, 128, hat maker |

|

Scott, John, 137-138 |

|

Shaw, D[aniel], 139-140, miller |

|

Smith, James, 141-142 |

|

Smith, S. R., 47-48, chair manufacturer, $1,800.00 |

|

Steel, Joseph, 145-146, farmer, $17,250.00 |

|

Taylor, Dr., 69-70 |

|

Turner, Wm. [Illegible], 133 |

|

Varner, Charles, 45-46, hatter |

|

Wade, Thomas M., 107-108, coppersmith, $4,000.00 |

|

Walkup, Samuel, 170-171, farmer, $100.00 |

|

Wallace, And., 105-106, farmer, $7,500.00 |

|

Wallace, Wm., 118 |

|

Weaver, Mr., 101-102 |

|

Webb, J[as.], 114 |

|

Whitlock, Mr., 89-90 |

|

Wilson, J. M., 197-198 |

|

Willson, James, 111-112 |

|

Winn, Joseph, 87-88, bricklayer, $2,500.00 |

|

Woodson, Saml., 446-447 |

|

Wright, James R., 96, silversmith |

|

Zollman, H., 42-43, farmer, $10,000.00 |

APPENDIX B: Clients of Thomas G. Chittum Who Paid Taxes on Enslaved People

Appendix B lists a sampling of clients according to the number of enslaved persons for whom they were taxed in 1850. The two categories on the yearly personal property tax were “slaves above 12” and “slaves above 16.”

There are two lists for the 1850 Rockbridge County Personal Property Tax. The tax list taken by Samuel Gold has twenty individuals Identified from Chittum’s client list in Appendix A that were taxed for owning enslaved individuals. The tax list taken Robert S. Campbell has fifteen individuals identified from Chittum client list in Appendix A that were taxed for owning enslaved individuals. Because both lists mirror each other in showing the diversity of the economic status of Chittum ‘s clients, Appendix B is a composite or sampling of both lists.

|

Samuel F. Jordan, slaves above 16: 11 |

|

Joseph Steel, slaves above 12: 4 & slaves above 16: 8 |

|

Hugh Barclay, slaves above 12: 2 & slaves above 16: 7 |

|

Matthew Kahle, slaves above 16: 1 |

|

John Kerr, slaves above 16: 4 |

|

Thomas M. Wade, slaves above 16: 3 |

|

Joshua Parks, none |

|

James Matheny, slaves above 12: 1 |

|

Geo. W. Adams, slaves above 16: 2 |

|

Alexr. McCowan, none |

|

F. Kurtz, none |

[1] Rockbridge County, Virginia, Chancery Court Case, Index No. 1855-005, John D. Camden vs. Thomas G. Chittum, Etc.; digital images, Library of Virginia, Chancery Records Index, available online: http://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=163-1855-005 (accessed 21 November 2022).

[2] See Barbara Crawford and Royster Lyle Jr., Rockbridge County Artists and Artisans (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1995); Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Southern Furniture 1680–1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection (New York: Abrams, 1997), 448–450; Kurt C. Russ and Jeffrey S. Evans, “The Kahle-Henson School of Punched-Tin Paneled Furniture” in American Furniture 2012, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone, 2012; and C. Tracey Parks, “Moses Crawford: Tennessee’s Earliest Cabinetmaker Revealed, MESDA Journal, 2013 (Vol. 34), online: https://www.mesdajournal.org/2013/moses-crawford-tennessees-earliest-cabinetmaker-revealed/ (accessed 17 November 2022).

[3] Rockbridge County, Death Register, 1853–1870, 27, Rockbridge County Microfilm Reel 181, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[4] Goochland County, Marriage Register, 1730–1853, 46, Goochland County Microfilm Reel 38, Library of Virginia, Richmond., VA

[5] Auditor of Public Accounts, Personal Property Tax, Rockbridge County, 1828, James McClung’s District, Personal Property Tax Records Microfilm Reel 302, Library of Virginia, Richmond., VA

[6] Rockbridge County, Deed Book M: 176, Rockbridge County Microfilm Reel 7, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[7] Goochland County, Deed Book 18:94, Goochland County Microfilm Reel 7, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[8] Ibid, 122–124.

[9] Goochland County, Virginia, Chancery Court Case, Index No. 1796-010, Gideon Moss vs. Executors of John Moss, Deposition of Daniel Grubb, Image 13; digital images, Library of Virginia, Chancery Records Index, available online: http://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=075-1796-010 (accessed 21 November 2022).

[10] Klaus Wust, The Virginia Germans (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia, 1969), 97.

[11] Ann E. McCleary, “The Turnpike Town” in The Great Valley Road of Virginia: Shenandoah Landscapes from Prehistory to the Present (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia, 2010), 194–195.

[12] Kenneth E. Koons and Warren R. Hofstra, “Introduction: The World Wheat Made” in After the Backcountry, Rural Life in the Great Valley of Virginia 1800–1900 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee , 2000), xx-xxi.

[13] Ibid, xxvi.

[14] Lexington Gazette (Lexington, VA), 2 February 1838, 3–4.

[15] Hurst and Prown, Southern Furniture 1680–1830, 162. For more about James Rockwood while he was in Richmond, see MESDA Craftsman Database, ID 31206, online: https://mesda.org/item/craftsman/rockwood-james/31064/ (accessed 10 November 2022).

[16] Rockbridge County, Deed Book U:461, Rockbridge County Microfilm Reel 10, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid, 460–461.

[19] Lexington Gazette, 5 October 1838, 3-3.

[20] Rockbridge County, Deed Book AA:144, Rockbridge County Microfilm Reel 13, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[21] Lexington Gazette, 18 May 1838, 3–4.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Lexington Gazette, 25 May 1843, 3–1

[24] Lexington Gazette, 15 May 1850, 3–2.

[25] Ann Smart Martin, Buying into the World of Goods: Early Consumers in Backcountry Virginia (Baltimore: John Hopkins University, 2008), 68–69.

[26] Rockbridge County, Virginia, Chancery Court Case, Index No. 1855-005, John D. Camden vs. Thomas G. Chittum, Etc., Answer of Thomas G. Chittum, Image 20; digital images, Library of Virginia, Chancery Records Index, available online: http://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=163-1855-005 (accessed 21 November 2022).

[27] Ibid, Image 10. Frances Sarah Turner married Thomas G. Chittum on 23 April 1828 in Rockbridge County. Virginia, U.S., Compiled Marriages, 1740–1850, Ancestry.com; available online with subscription: https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/136967:3723 (accessed 16 December 2022).

[28] See Charles W. Wooten and Barbara E. Kemmerer, “The Changing Genderization of Bookkeeping in the United States, 1870–1930,” The Business History Review, Vol. 70, No. 4 (Winter 1996), 548.

[29] Rockbridge County News, 13 February 1902, 2-5.

[30] Crawford and Lyle, 190. See also MESDA Craftsman Database, ID 94367, online: https://mesda.org/item/craftsman/bogus-enoch/93630/ (accessed 10 November 2022).

[31] Ibid, 223. See also MESDA Craftsman Database, ID 36447, online: https://mesda.org/item/craftsman/smith-samuel-r/36259/ (accessed 10 November 2020).

[32] Crawford and Lyle, 207-208; Rockbridge County, Virginia, Chancery Court Case, Index No. 1855-005, John D. Camden vs. Thomas G. Chittum, Etc., Account of Matthew Kahle, Image 282; digital images, Library of Virginia, Chancery Records Index, available online: http://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=163-1855-005 (accessed 21 November 2022). See also MESDA Craftsman Database, ID 93965, online: https://mesda.org/item/craftsman/kahle-mathew-s/93232/ (accessed 10 November 2022).

[33] Rockbridge County, Will Book 14:352-353, Rockbridge County Microfilm Reel 28, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[34] Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Coffin Making and Undertaking in Charleston and its Environs, 1705–1820,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Vol. 16, No. 1 (May 1990): 21, 38; available online: https://archive.org/details/journalofearlyso1611990muse/page/18/mode/2up (accessed 21 November 2022).

[35] William Benjamin Alexander, Ledger, 1850–1888, pp. 15, 22b, 30, 49, 50, Accession 29658, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[36] Crawford and Lyle, 206–207. See also Jordan Family Collection, 1752–1992, Accession 42492, Business Records Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[37] John J. Zaborney, Slaves for Hire, Renting Enslaved Laborers in Antebellum Virginia (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 2012), 120–121.

[38] Ibid.

[39] The English and Welsh seem to have the term “dresser” for this form while Germans most often used the term “cupboard.” Mary Ellen Snodgrass, The Encyclopedia of Kitchen History (New York and London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2004), 128.

[40] Kurt C. Russ and Jeffrey S. Evans, Opening the Door: The Safes of the Shenandoah Valley (Winchester, VA: Museum of the Shenandoah Valley, 2017), 7-9.

[41] Rockbridge County News (Lexington, VA), 27 February 1936, 6-3.

[42] Crawford and Lyle, 189, 219.

[43] J. Christian Kolbe, “The Account Book of Sampson Diuguid, Lynchburg, Virginia, Cabinetmaker,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Winter 2004): 19, available online: https://archive.org/details/journalofearlyso3022004muse (accessed 21 November 2022).

[44] For instance, there is no way to know what assets individuals had in cash, money loaned out, money in the bank, and stock owned. These types of assets usually only appear in an estate account of a deceased individual. In addition, the number of enslaved people in a region primarily producing grains would be less than in areas growing tobacco because cultivation of grains is less labor intensive than tobacco. In the same vein, residents of towns would not have a need to enslave as many laborers as the owners of large tracts of cultivated land.

[45] Rockbridge County, “Free Negro Register,” 1831–1860, 41, Rockbridge County Microfilm Reel 90, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[46] Failure to pay personal property tax could result in free African Americans being hired out to another individual to pay off the tax.

[47] Gregory Crawford and J. Christian Kolbe, Judgments (Richmond, VA: The Library of Virginia, 2007), available online: http://digitool1.lva.lib.va.us:8881/R/SKQKDTRYNNHX9IABBLNUEN28NSFSMXL59TGCLU4BK3725HJ5I7-04392?func=dbin-jump-full&object_id=5160&pds_handle=GUEST (accessed 21 November 2022).

[48] Rockbridge County, Deed Book DD:451-452, Rockbridge County Microfilm Reel 14, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[49] Rockbridge County, Death Register, 1853–1870, 27, Rockbridge County Microfilm Reel 181, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[50] Rockbridge County, Will Book 15:382, Rockbridge County Microfilm Reel 28, Library of Virginia, Richmond. The 1860 Code of Virginia allowed heads of household in debt to specify items that could not be seized by creditors (The Code of Virginia, 2nd ed., Including Legislation to the Year 1860 [Richmond, VA: Ritchie, Dunnavant and Company, 1860], 286).

[51] J. Christian Kolbe, “Willis Cowling (1788–1828): Richmond Cabinetmaker,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Vol. 27, No. 2 (Winter 2001), 57, available online: https://archive.org/details/journalofearlyso2722001muse?view=theater (accessed 21 November 2022).

© 2022 Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts