|

The United States’ new capital city was an odd choice for a portrait painter at the end of the eighteenth century. While Boston and New York were centers of artistic training and activity, when Washington was founded in 1790 it was sometimes referred to as the “Mud Hole” and the “Wilderness City.”[1] Washington resident Marcia Burnes Van Ness went so far as to note that the city had “trails for streets that ran between surveyor’s stakes in the tobacco fields.”[2] Adding further color to early accounts of the city, in 1834, William Dunlap, an artist and chronicler of the arts and theater, republished exaggerated remarks by one writer who had described Washington at the end of the eighteenth century as “morass and forest, the abode of reptiles, wild beasts, and savages.”[3] A developing city bustling with building activity, Washington may not have been an artist’s dream locale, but it was the perfect place for a house painter — or a portrait painter who could also paint houses! — and had struggled to find success in New York. By 1798, the President’s House, the Treasury Building, and the Capitol Building that would house Congress were all under construction and they would need a painter, as might the people occupying them.

Arriving in the city in 1797, Lewis Clephan was one of the few portrait painters who worked in the nation’s new capital – Washington, the District of Columbia – prior to 1800. Skilled as a house painter as well as a portrait painter, Clephan probably knew of the flurry of building activity that defined the early years of Washington, DC, and his move to the city was likely as much for trades painting as for portrait painting. Evidence for piecing together the contours of Lewis Clephan’s early years in Washington are scattered across miscellaneous sources. Bringing them together provides insight into the range of work he was doing in the capital, from house painting, to portraits, to selling materials for both trades. Despite, or perhaps because of, the range of work Clephan undertook during his time in the city, he has been largely overlooked by scholars. In 1983 Andrew J. Cosentino and Henry H. Glassie published what was known about the artist and illustrated the only portrait then known by his hand, the signed and dated 1788 portrait of John I. Remsen of New York City (Figure 1).[4] Subsequent research notes made by the late Whaley Batson and MESDA’s acquisition of seven portraits by Clephan created either in Washington or nearby in Maryland provided a broader biography of the painter and understanding of his idiosyncratic style.[5] This article further adds to our understanding of Clephan’s biography and provides a catalogue raisonné of the portraits currently attributed to the artist. It is hoped that by bringing all his known work together for the first time, this article will spark further research into his painting style, his connections, and those of his sitters in the Early Republic.

Biography

Lewis Clephan was born “Ludowick” Clephan on 13 January 1754 in the South East Parish of Midlothian, Edinburgh, Scotland, to John Clephan (1724–?) and his wife Condradina Murray Clephan (1733–?).[6] Details of Clephan’s early life are unknown, although records indicate he had at least two siblings, Thomas Clephan (1752-1829), and James Clephan (1754-?).[7] While neither of Clephan’s brothers appear to have immigrated to America, his nephew James Clephane (1790-1880) would later join his uncle in Washington, DC.[8] Clephan initially settled in New York City, where he married Ann Shaw in 1788.[9] Two years later, the 1790 census documents him as living in the city’s South Ward in a household comprised of four members, including two females and two males 16 years old or older.[10]

Where and with whom Clephan trained as a painter are unknown, but the advertisements he placed in American papers indicate that he had training in house and related painting trades. His identified portraits further suggest that he had instruction in miniature portrait painting, a format especially popular in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. By 16 May 1787, Lewis Clephan was established enough in New York City to place the following advertisement in The Independent Journal: or, General Advertiser:

Lewis Clephan

Portrait Painter

Begs leave to acquaint the Ladies and Gentlemen, that he has removed from Chapel-Street to Crown Street, No. 28, where he Paints Likenesses, whole, half and quarter Lengths, on the lowest and most reasonable Terms.—He therefore returns his most grateful acknowledgements for the Encouragement he had already received, and hopes a continuance of their Favors; he bids himself, if his Likenesses are not Striking and approved of, he requires no pay. Any Ladies or Gentlemen who please to favor him with their Employ, may depend upon the strictest Attention being paid to their Orders, and their Business done with the Greatest Attention and Dispatch

N.B. Miniature Painting, Hair Work, etc. done in the neatest Manner.[11]

From the advertisement it is clear that Clephan had been active in the city long enough prior to placing the ad to have completed more than one portrait as he acknowledged his gratitude for previous commissions. Working within established conventions for portraiture in both Britain and America at the end of the eighteenth century, the advertisement states that he does various types of portraits: whole, half and three-quarter-lengths, and miniatures.[12] Examples of the artist’s whole, three-quarter and half-length portraits are known; all are on small supports and under life size. Miniature portraits by his hand have yet to be discovered.

In the years immediately following his marriage to Ann, Clephan is listed in the New York City Directory as “Clephan, Lewis, painter,” and the 1791 directory lists his residence as 1 Verletenbergh Street. [13] However, by the 1792 and 1793 directories, a “Clephan, Louis, soap-boiler and tallow-chandler” is recorded at the corner of Verletenbergh and New Streets.[14] It is possible that in the early 1790s Clephan turned to making soap and candles because he was faced with competition from other artists working in New York City, many of whom were better trained and more skilled. It may also be that his inability to find steady work as a portrait painter prompted his decision to leave New York and move to the District of Columbia where he may have hoped to be able to leave the tallow behind.

There are currently no known records noting his activities between 1793 and 1797, but it is likely that Clephan worked in one or more cities prior to Washington, perhaps facing similar competition and thus disappointment. Even at the end of the eighteenth century it was not uncommon for artists to move from city to city for work. Whatever he was doing between 1793 and 1797, by the spring of 1797 Clephan was established in the District of Columbia and placed his first advertisement in the Washington Gazette, an amusing one for a runaway apprentice whose return was clearly unwanted.

HALF A CENT REWARD

Ran away from the subscriber, on the 17th of March last, an indented Apprentice to the Painting Business by the name of Thomas Read. As his indenture is missing, it is supposed he stole it and carried it with him. Any person who will return said Apprentice to me, the subscriber, shall receive the above reward, without thanks or charges.

Lewis Clephan

City of Washington April 17, 1797[15]

However, much like his experience in New York City, Clephan found he needed to augment his portrait income with other business ventures while in the District of Columbia. This was not unusual; many other artists of his day likewise found themselves in similar predicaments. In addition to portrait painting, Clephan relied on his skills in house painting and selling materials related to his trade. By 1799 Clephan had established important relationships with several influential leaders in the District of Columbia, including Dr. William Thornton, the first architect of the United States Capitol building and superintendent of the United States Patent building. In a letter dated 10 August 1799 addressed to George Washington from Thomas Law, the husband of George Washington’s granddaughter Eliza Parke Custis and a leading investor and developer of the new capital, Law describes spending a pleasant evening with “Thornton the Architect[,] Cliffin [Clephan] the Poet & Painter, Bernard the Actor & Darley the Singer….”[16] Clephan likely leveraged these new networks and connections to advance both his portraiture business — with the likeness of the builder Leonard Harbaugh (Figure 2) as one such example — as well as his house painting business.

Four mentions of Clephan in the diary of Mrs. William Thornton, the wife of Dr. William Thornton, illustrate the breadth of work he was doing beyond portrait painting. On the morning of 6 January 1800, Mrs. Thornton “stopped at the Capitol to get Mr. Clephan to put a glass into an oval picture frame” and, again on 8 January, she sent “Joe” to get another glass from the artist to replace the one she broke.[17] By this time Clephan was working for Dr. Thornton supplying glass for the Capitol, and he submitted an advertisement in August 1803 that ran in numerous issues of Washington papers until spring of 1804 informing potential customers that he sold sheet glass “cut to any size” at his shop east of the Branch Bank on F Street. He also noted that “Gentlemen sending their Sashes to the subscriber will have them neatly glazed and on moderate terms.”[18] In this same ad, he listed painters’ colors of all sorts, linseed oil, spirits of turpentine, and gold and silver leaf by the pack or book. Records from 1801 indicate that he was also drawing on his training in house painting as he was due $1,500 for his work painting in the Capitol building and the President’s House.[19] By 1802 his business relationship with Thornton and others involved in erecting new buildings in Washington included “painting work of every sort and kind” at the Octagon House, a home designed by Thornton for the wealthy Virginia plantation owner Colonel John Tayloe III.[20]

Other references to the artist’s activities in Washington in the first decade of the nineteenth century include mentions of his role as an executor of David Ogilvie’s will, written in 1804 and proven on 19 April 1805.[21] Clephan was appointed the guardian of Ogilvie’s daughter Anne until she was 16 years old. In 1819, Anne married Lewis’s nephew James Clephane who emigrated from Scotland and lived with his uncle.[22] Around this time Clephan is also listed as having an “account” with the Washington Theater, an enterprise that held its first performances in 1804. The building of the theater was financed through accounts, or “subscriptions,” paid in cash or through work performed in trade. Lewis Clephan’s account was probably for painting or glazing.[23] This same year, Clephan was naturalized as a United States citizen.[24]

In addition to his painting trade, Clephan was appointed with architect James Hoban to one of five committees in the city to obtain contributions “for the purpose of taking into consideration the necessities of the poor…”[25] It was also around this time that he was listed on the ticket for city council men and sought to collect on a voucher for $5.50 for “Linseed Oil & spanish Whiting” used at the President’s House.[26] In 1807 Clephan announced his plan to publish by subscription an east view of the Capitol and a south view of the Navy Yard. He noted that the project was sanctioned by the President of the United States and that the engravings would be executed by a well-known artist. Whether or not this project was realized is unknown; no engraved views of the type described in the advertisement have been identified.[27]

Clephan was also involved in various property transactions, several of which pointed to impending financial distress. In the years between 1804 and 1807 he was included in the sale of a dwelling house near Square 170 by which Clephan was due $110 on a mortgage.[28] An 1809 notice in the National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser indicated that a lot on Eighth Street, which included a two-story brick house, was ordered to be sold to satisfy a judgment in favor of Lewis Clephan.[29] He had won his suit against the owner of the property to collect debts due to him, but by 1814, Clephan was seeking additional income. He advertised that “Six or seven gentlemen can be accommodated with lodgings, at that elegant three-story house on F street.”[30] The house on F Street that he had occupied since at least 1803 was offered for sale in 1815, 1817, and for sale or rent in 1819.[31] Clephan may have been in financial trouble in 1819 because the next year he sold personal property to pay city taxes he owed from 1819 and earlier years.[32]

Among the most interesting references to Clephan are those recorded for 1830. On 22 April, Clephan and John Gardiner (c. 1770–1839) wrote to President Andrew Jackson with a request to borrow and copy the “Indian portraits displayed in the War Department.” The President forwarded their request to the Secretary of War, John H. Eaton, adding “that it might be well to permit them to copy the pictures if they will do so, in the Portrait room—they ought not to be taken from the room.”[33] Eaton in turn requested that Colonel Thomas L. McKenney, Superintendent of Indian Trade/Superintendent of Indian Affairs, advise Clephan and Gardiner. On 26 April, McKenney denied the request because he had previously refused other artists who wanted to copy the portraits.[34] The next day, Clephan and Gardiner wrote President Jackson again:

We trust you will grant our petition, & thus gratify the curiosity of those who wish to see the Portraits & pay for us for the sight at their own homes, instead of coming to this City to see them. . . [I]t is strange that a subordinate clerk [McKenney] should dare to refuse to permit the Artists of the Republic to copy the Public paintings for the gratification of all the Citizens who may be willing to pay the Artists for their labor in Copying them, and who cannot conveniently come to the Seat of Government.[35]

Presumably, this request was also denied since Clephan and Gardiner persisted with a slightly modified request to Eaton to “trust us with two or three portraits at a time for a few days for copying.”[36] Eaton or McKenney refused this request as well. The latter collaborated with James Hall (1793–1867) and the artist Charles Bird King (1785–1862) to write and illustrate the History of the Indian Tribes of North America, published between 1836 and 1844.[37]

The business relationship between Clephan and John Gardiner seems to have been brief and only for the purposes of making copies of the “Indian portraits.” Several advertisements by a John Gardiner, an upholsterer from Dublin, appear in Washington papers beginning in 1802. There are no references to painting of any sort in these references.[38]

A death notice published on 5 November in the New York Evening Post announced that Clephan died in Washington in 1833.[39]

Catalog of Known Portraits by Lewis Clephan

This section of the article discusses the known portraits attributed to Lewis Clephan. In addition to the 1788 New York likeness of John I. Remsen Sr. (Figure 1), the portraits now attributed to him include Leonard Harbaugh, Otho Berry Beall, Mary (Berry) Beall, Benjamin Berry, two portraits of Zachariah Berry, and a double portrait of Zachariah Berry’s children. Being able to study these paintings as a group may lead to further attributions.

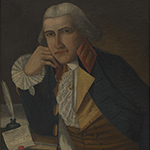

John I Remsen Sr (1750-1815)

The painting is inscribed on the paper below the inkwell “M.r John I. Remsen/Merct/N. York” and at the upper right corner “Lewis clephan Pin.xt/1788”.

This portrait is the earliest of the known works identified or attributed to Clephan. John I. Remsen was born in New York around 1750 and married a woman named Dorothea in New York City in 1781.[40] He worked as a merchant in the city until his death on 29 April 1815.[41] The sitter’s pose, with his elbow resting on a table and relaxed hand at his face, is typical of the period but is not seen in other works by the artist. Clephan’s ability to paint convincing fine detail is especially apparent in this portrait in the lace cuff and jabot, feather pen, ink bottle, and letter. The sitter is wearing a white wig and has a small stickpin in his elaborate lace jabot. Although Remsen appears to be dressed in a British army officer’s uniform, he served in the New York 2nd Regiment during the Revolutionary War.

Leonard Harbaugh (1749-1822)

On the back of the frame is the old inscription “Died/September/ 11th 1822 and buried in the National Yard [Congressional Cemetery].” There are other inscriptions on the verso that cannot be deciphered.

Leonard Harbaugh was born at Kreutz Creek, York County, Pennsylvania on 10 May 1749. He married Rebecca Reinbeck (1754–1801) of Germantown, Pennsylvania, and the couple had fourteen children. Harbaugh died in Washington, DC, 10 September 1822.[42]

Harbaugh was a successful inventor, builder, carpenter, and designer who worked in Baltimore beginning in the 1770s. By the 1790s his ventures into various import/export businesses had failed, putting him in considerable debt. He and his family soon fled, first to Frederick, Maryland, before settling in Washington, DC, in 1792. There Harbaugh built the old War and Treasury buildings. He assisted in the rebuilding of the Capitol building after it was burned by the British in 1814. Harbaugh is also credited with much of the work in opening the channel of the Potomac River above Washington. It is very likely Clephan and Harbaugh knew each other from one or more of these projects since both men were actively working on some of the same buildings.[43]

Harbaugh’s portrait, at 9 1/2″ high, is the smallest likeness currently assigned to Clephan. While not a miniature, it provides some idea of the artist’s ability to successfully render human figures significantly under life size. The face and costume details are crisply painted, and the sitter seems relaxed in his seated pose. The draped proper right hand with closely held fingers is seen in other Clephan portraits.

Benjamin Berry (1768-1815)

A modern inscription on the back of the canvas states that “the following was on the back of the original canvas ‘Benjamin Berry, Esq./Born in ye year/1739/on July 16th O. L./ Lewis Claphane, Painter.’“

Benjamin Berry was born in Montgomery County, Maryland, to John Berry (1736–86) and Eleanor Bowie Clagett (1740–86). In 1787, Benjamin Berry married Eleanor Lansdale (1769-94), and the couple had three children: Eleanor Berry (1788-?), Thomas Lansdale Berry (1789-1856), and John Berry (1791-1856). After Eleanor’s death in 1794, he married Elizabeth Ridgely Dorsey (1765–1839?).[44] Early in their marriage the Berrys resided in Ritchie, Prince George’s County. Their plantation property, described as being within 13 miles of Washington, was advertised for sale in Baltimore papers in 1801. Berry noted that he, the advertisement’s subscriber, formerly lived on the plantation and was at present a brick maker living on Lee Street in Baltimore.

In 1803, Berry advertised that he was operating two brick yards and wanted to sell one of them.[46] Both of these businesses were likely located in the vicinity of Lee and Sharp Streets, near Baltimore’s busy waterfront and wharfs, often referred to in advertisements as the “Basin” or “Bason.” The last listing for Berry’s brick making businesses in The Baltimore Directory and Register, for 1814–15 gave the location as the southeast corner of Lee and Sharp Streets. Listed in the same directory was the brickmaker John Berry, who was located across the street on the southwest corner of Lee and Sharp Streets.[47] John was most likely Benjamin’s son from his first marriage. In July 1815, Benjamin Berry ”departed this life. . . at the seat of Dr. A. [probably Archibald] Dorsey.”[48] John Berry took over his father’s brick yard after Benjamin‘s death. By August 1815, John Berry took his brother Thomas L. Berry as a partner in “the Brick Making Business.”[49]

Otho Berry Beall (1790–1853)

Otho Berry Beall was born in Montgomery County, Maryland, the son of Samuel Brooke Beall (1762–1828) and his first wife Eleanor [Elinor] Berry Beall. On 16 January 1813, Otho married Mary Berry (1780–1853) (Figure 5), the daughter of Zachariah Berry Sr. (Figure 6 and Figure 7) and the couple had at least three children. According to family history, the family lived at Westphalia, also known as White House Place, on White House Road near Ritchie in Prince George’s County.[50] The portraits of Otho and Mary were probably painted soon after their marriage. They are shown as young adults, have identical original gilt frames, and measure the same size. Both subjects are seated with similar curtains and tassels in the background, and they both have hands with tightly closed fingers. All of these elements can be seen in other works by the artist.

Mary Berry Beall (Mrs. Otho Berry) (1780–1853)

Mary Berry Beall was the daughter of Zachariah Berry Sr. (Figure 6 and Figure 7) and his wife Mary Williams Berry (1749-1805).[51] The flowers and basket, her double laced collar, and the vine decoration on the chair back demonstrate Clephan’s ability to convincingly render small details. Mary and her husband’s portraits descended to their son Washington Jeremiah Beall (1818–95) and once hung in his home, Mt. Lubentia, a plantation that Otho Berry Beall purchased and conveyed to his son about 1839.[52]

Zachariah Berry Sr. (1749–1845)

There are two three-quarter length Clephan portraits of Zachariah Berry Sr., this example and a second showing him as a slightly younger man with darker hair (Figure 7). Here, a column and a draped blue curtain with fringe provide the backdrop for Berry who holds a book and sits in an upholstered chair that is likely leather with prominent rows of brass tacks. His meticulously painted watch fob hangs at his waist on his proper right side in both portraits. Berry was a wealthy tobacco farmer who enslaved at least sixty-nine people of African descent; he built and raised his family at Concord Plantation in Prince George’s County, Maryland.[53]

The sitter was the son of Jeremiah Berry (1712–69) and Mary Claggett Berry (1715–92). Zachariah was the father of the two boys shown in figure 8 and Mary Berry Beall (Figure 5), the wife of Otho Berry Beall (Figure 4). He married Mary Owen Williams (1749-1805) of Georgetown, DC in 1777.[54] His will, probated in Washington on 2 April 1845, indicates that it was written in Prince George’s County, Maryland. Zachariah may have been in Washington at the time of his death since he owed land in the city and had a son living there.[55] Zachariah and his wife Mary Owen Williams Berry are buried at Concord Plantation in the family cemetery.

Zachariah Berry Sr. (1749–1845)

This portrait may have been painted either a few years before the one illustrated in figure 6 or it may have been painted later, as a copy for one of the children. The figure 6 portrait is more elaborate in its setting with the brass-tacked chair, fringed curtain, and what is probably an account book held by the sitter. Except for the likeness of John Remsen (Figure 1), men in Clephan’s portraits tend to be small in stature and portly. Whether these physical traits reflect the artist’s idiosyncratic style or were accurate to the subjects is unknown.

Zachariah Berry’s Sons (probably Zachariah Berry Jr., 1785–1859, and Washington Berry, 1790–1856)

This portrait descended in the Berry family but the identity of the two sitters was not recorded. They are probably Zachariah’s youngest sons since his two other sons would have been in their late teens or early twenties in 1800. These two sons, like Zachariah’s other children, inherited considerable land from their father.

The boys are shown in an interior setting with a draped red curtain above an alcove and a carpeted floor. Their dog is between them. One son holds a stick or cane while the other has a hat in his proper right hand. The attribution of this painting to Clephan is based on its history of descent with likenesses of Zachariah Berry (Figure 6 and Figure 7), the loosely painted style of the red curtain, and the portrait’s nearly identical size to other Berry family portraits. By comparison with those, the faces and dress in the children’s likeness is sketchy and less refined.

Carolyn J. Weekley is the former Juli Grainger Director of Museums for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and the author of Painters and Painting in the Early American South (2013).

[1] United States Marine Corps Publicity Bureau, The United States Marine Corps Band; Its History and Acheivements; A Message for Musicians (Philadelphia: United States Marine Corps Publicity Bureau, 1937), 8.

[2] Frances Carpenter Huntington, “The Heiress of Washington City: Marcia Burnes Van Ness (1782–1832),” Records of the Columbia Historical Society 69/70, (Washington, DC: 1969–70): 84.

[3] William Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of The Arts of Design in the United States (New York: George P. Scott and Co. Printers, 1834): 1, 339. Other sources describe the difficulties of traveling to and from the city and its sparse population. See Evelyn Levow Greenberg, Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, 48, no.1 (September, 1958): 1–19, which states there were about 370 houses in the city, of which 107 were brick.

[4] Andrew J. Cosentino and Henry H. Glassie, The Capital Image: Painters in Washington, 1800–1915, (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1983) 21, 24, and fig. 1. Leila Mechlin was probably the earliest historian to discuss Clephane and other artists who worked in Washington, DC in her article “Art Life in Washington,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, vol. 24 (1922):164–191. “Clephan” is the spelling of his name in most documents; occasionally it is spelled “Clephane,” as it is when referring to some of his relatives and descendants.

[5] Whaley Batson’s research notes and correspondences (1973-1988) on the artist Lewis Clephan are located in the MESDA Object Database files, “Paintings/ Clephan, Lewis.”

[6] “Scotland Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950,” database, FamilySearch, online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:F319-W9Q (accessed 20 July 2023).

[7] Thomas Clephan’s birth is recorded on 12 May 1752; “Scotland Births and Baptisms, 1565-1950,” database, FamilySearch, online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:F31M-B9K (accessed 29 September 2023). James Clephan is recorded as being born to John Clephan and Condradina Murray on the same date that Lewis Clephan was born, 13 January 1754. ”Scotland Births and Baptisms, 1565-1950,” database, FamilySearch, online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XYWX-BL9 (accessed 29 September 2023).

[8] James Clephan[e] (his name usually spelled with the “e” in records) was the son of Thomas Clephan and father of Lewis (1825-1898), a politician credited with leading the Republican Party during much of his lifetime. James was also the grandfather of the well-known artist Lewis Painter Clephane. See Walter C. Clephane, “Lewis Clephane: A Pioneer Washington Republican,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, 1918, 21:263-277.

[9] “Records of the First and Second Presbyterian Churches of the City of New York,” The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record 14, issue 2 (1882): 94.

[10] 1790 United States Federal Census, South Ward, New York City, NY, 1.

[11] The New-York Historical Society Quarterly Bulletin, 4, no 1 (April 1920): 27, online: https://digitalcollections.nyhistory.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A5446#page/27/mode/2up (accessed 12 July 2023). Frederic Fairchild Sherman, “Some Recently Discovered Early American Portrait Miniatures,” Antiques II (April 1927): 296. Sherman notes that Clephan painted miniatures in Connecticut in 1787, though he gives no source for the claim, and no examples of Clephan’s work in Connecticut have been found.

[12] For a discussion of the standardization of portraiture sizes see: Robin Simon, The Portrait in Britain and America: With a Biographical Dictionary of Portrait Painters, 1680–1914 (London: G. K. Hall, 1987): 111–12.

[13] The New York City Directory, 1789, 21, online: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/86f759e0-da8e-0134-7249-71f128b48285 (accessed 13 July 2023); The New York City Directory, 1790, 24, online: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/dfc54ca0-e67b-0134-0aa0-5ddffb4c30ce (accessed 13 July 2023); The New York City Directory, 1791, 24, online: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/c17c01a0-ea58-0134-e644-063df2ab41c5/book#page/41/mode/2up (accessed 12 July 2023).

[14] New York City Directory, 1792, 26, online: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/ed1966f0-69aa-0135-b0a4-7f9b879b56cd (accessed 13 July 2023); New York City Directory, 1793, 29, online: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/eb687a50-3cb3-0135-cf9a-318ca6fcafdb (accessed 13 July 2023).

[15] Washington Gazette, Washington, 19-22 April 1797: 3.

[16] Thomas Law to George Washington, 10 August 1799, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-04-02-0194 (accessed 30 September 2023). Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 4, 20 April 1799 – 13 December 1799, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999, pp. 231–233.

[17] Worthington C. Ford, “Diary of Mrs. William Thornton, 1800-1863,“ Records of the Columbia Historical Society 10 (1907): 91, 93. These entries were for January 6 and 8, 1800, online: https://archive.org/details/jstor-40066957/page/n5/mode/2up (accessed 13 July 2023).

[18] Ibid., 112. This entry was from 27 February 1800, online: https://archive.org/details/jstor-40066957/page/n25/mode/2up (accessed 13 July 2023); The National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser, Washington, 3 August 1803, 12-19 October 1803, 11–14 November 1803, 23–28 December 1803; 4 January 1804, 1 February 1804. These ads generally appear on pages 3 or 4, except for 12 October 1803 which is on page 2. Clephan placed similar advertisements in the Washington Federalist, Georgetown, DC, 21 May 1804, 28 May 1804, 12 September 1804. The National Intelligencer, Washington, 11 November 1814. In the latter issue he offered lodgings at his house on F Street in Washington.

[19] See: Message from the President of the United States: Transmitting a Representation of the Commissioners of the City of Washington, Relative to the Affairs of the City, printed by William Duane, Washington City, 1802, Document G-4. Indicates that Lewis Clephan was due $1,500 for the painting of the Capitol and the President’s House.

[20] Lewis Clephan’s account with John Tayloe, 1802, Tayloe Family of Richmond County, Va., Papers, 1650–1970. 27,925 items. Mss1 T2118d. Microfilm reels C163–213. Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, VA. Photocopy in MESDA Object Database files, ”Paintings, Clephan, Lewis.”

[21] Shannon Green, “Broadening Search Parameters: A Case Study,” The National Genealogical Society Magazine 44, no. 2 (April-June 2018): 53-56.

[22] Ibid; “Marriage notice,” Belfast Newsletter, 8 February 1820, 3.

[23] AnnMarie T. Saunders, “‘To the Advantage of the City’: Playgoing, Patriotism, and the First Washington Theatres, 1800–1836” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Maryland, 2012), 54.

[24] “Index to the Naturalization Records of the U. S. Supreme County for the District of Columbia, 18-2-1909,” U. S. Naturalization Records Indexes, 1794–1995, Microfilm Serial M1827, roll 1, 55, National Archives and Records Administration, online: https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1192/images/M1827_1-0039 (accessed 14 July 2023). James Clephan is listed with a naturalization date of 1833 below Lewis on the same page of the index.

[25]The Intelligencer National and Washington Advertiser, Washington, 23 January 1805, 3. James Hoban immigrated from Ireland and established himself as an architect in Philadelphia in 1785. In 1792, Hoban won the design competition for the White House in Washington and moved to that city. Hoban also served as a supervising architect on the building of the Capitol and worked closely with its designer, Dr. William Thornton. Clephan would have been familiar with both of these men and others, including Leonard Harbaugh (Figure 2), as all of them were involved in the government’s building projects.

[26] The National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser, Washington, 22 May 1805, 3; Founders Online, “Monies Expended on the President’s House 1807. 31 December 1807,” online: https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Monies%20Expended%20on%20the%20President%E2%80%99s%20House%201807.%2031%20December%201807&s=1111311111&sa=&r=1&sr= (accessed 1 July 2023).

[27] Washington Federalist, Georgetown, 16 December 1807, 3.

[28] Washington Federalist, Georgetown, 1 December 1804, 3.

[29] National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser, Washington, 15 March 1809, 3.

[30] National Intelligencer, Washington, 11 November 1814, 3.

[31] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, 10 August 1815, 3; 25 July 1817, 1.

[32] Ibid., 21 July 1820, 3.

[33] Daniel Feller, Thomas Coens, Laura-Eve Moss, eds. The Papers of Andrew Jackson, VIII, 1830 (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2010): 213-214, online: https://trace.tennessee.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1006&context=utk_jackson (accessed 2 July 2023).

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Independent American and Columbian Advertiser, Georgetown, 5 September 1809, 5; Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, 25 April 1817, 3.

[39] New York Evening Post, New York City, 5 November 1833, 5. The notice reads “[Died] At Washington, DC on Saturday last, Mr. Lewis Clephane, aged about 81, a native of Scotland—the first person who introduced the manufacture of white lead into the United States.”

[40] New York Marriage Index, 1600-1784 32: 88, Record Number M.B., online: https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/12802:4205 (accessed 20 July 2023).

[41] The Evening Post, New York, 29 April 1815, 2.

[42] MESDA accession file 2501, online: https://mesda.org/item/collections/leonard-harbaugh/1187/ (accessed 17 July 2023). Other sources on Harbaugh’s biography include Todd Andrew Dorsett, ed., “The Harbaugh Family,” Antietam Ancestors, I, no. 3 (Summer 1984): 56–63, 66–70. Another version of this painting appeared in Antiques Magazine (December 1942): 324–325. Its location is unknown. Assigning attribution to Clephan based on the illustration is difficult; however, the prominent vertical crack in the support suggests that it is oil on a wood panel, similar to MESDA’s portrait of Harbaugh.

[43] Ibid. For additional details on his work and his business failures, see The Maryland Gazette or, the Baltimore Advertiser, Baltimore, 18 November, 1788, 3; 9 October 1789,3; Gazette of the State of Georgia, Savannah, 12 June 1788, 2–3; Maryland Journal & Baltimore Advertiser, Baltimore, 6 May 1788, 2; 15 December 1789, 3 Virginia Herald, Fredericksburg, 30 July 1789, 2; 6 August 1789, 3; Maryland Journal & Baltimore Advertiser, Baltimore, 29 December 1789, 3; 5 January 1790, 2; 12 January 1790, 3; Maryland Journal and Baltimore Advertiser, Baltimore, 15 January 1790, 4; 26 January 1790, 3; 28 January 1790, 4; 19 February 1790, 3; 9 March, 1790, 4; 26 March 1790, 3; 30 March 1790, 4; 2 April 1790, 4; 16 April 1790, 3; 3 September 1790, 1, 3; 14 December 1790,3; 29 April 1791, 3; 21 March 1794; The Baltimore Daily Intelligencer, Baltimore, 20 March 1794, 2–3. See also Garrett Power, “The Carpenter and The Crocodile,” Maryland Historical Magazine, 91, no. 1 (Spring 1996): 5–15; Glenn Crothers, “Agricultural improvement and Technological Innovation in a Slave Society: The Case of Early National Northern Virginia,” Agricultural History, 75, no. 2 (Spring 2001): 142.

[44] George Norbury Mackenzie and Nelson Osgood Rhoades, eds., Colonial Families of the United States of America: in Which is Given the History, Genealogy and Armorial Bearings of Colonial Families Who Settled in the American Colonies From the Time of the Settlement of Jamestown, 13th May, 1607, to the Battle of Lexington, 19th April, 1775 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1966, 1995), 2: 114-116, online: https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61175/images/colonialfamiliesii-001069_116 (accessed 17 July 2023). See also Mary E. Quillen Honeywell, “The Du Bury-Berry Family in General: The Benjamin Berry Family in Particular,” (Mary E. Quillen Honeywell, 1970), 150-151, online: https://www.seekingmyroots.com/members/files/G000191.pdf (accessed 17 July 2023).

[45] Federal Gazette & Baltimore Daily Advertiser, Maryland, 17 June 1801, 3. This describes his plantation in Montgomery County in detail. While living in Baltimore, Berry is listed as enslaving six individuals in his household in the 1810 census. It is not known whether these individuals were forced to labor in Berry’s brick yards. 1810 United States Census, Baltimore Wards 2 through 6, Baltimore, Maryland, p. 157, online: https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7613/images/4433406_00089https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7613/images/4433406_00089 (accessed 28 September 2023).

[46] Federal Gazette & Baltimore Daily Advertiser, Maryland, 26 October 1803, 3.

[47] In 1807 and 1814, Berry advertised dwellings for rent—one presumably in the Lee Street area and the other at the Corner of Sharp and Lee Street. Federal Gazette & Baltimore Daily Advertiser, Maryland, 10 August 1807, 3; Baltimore Patriot & Evening Advertiser, Maryland, 4 May 1814, 3. Various Baltimore city directories list him in this area until 1814.

[48] American & Commercial Daily Advertiser, Baltimore, Maryland, 20 July 1815. Benjamin Berry was interrelated to the Dorsey’s through marriage to Elizabeth Ridgely Dorsey. Her mother was Elizabeth Ridgely who married Thomas Dorsey. Their son (and Elizabeth Dorsey Berry’s brother) Theodore Dorsey lived on the property adjoining “Dr. A.[Archibald] Dorsey” where Benjamin died. Theodore may have inherited a brick yard from his father since he and his mother had a brick making business on their property in Spring Gardens. Their relationship to Archibald Dorsey is uncertain. Benjamin Berry was the Administrator of Theodore Dorsey’s estate in 1812 and, after Elizabeth Dorsey’s death Benjamin was involved in selling her property. See Baltimore Evening Post, Maryland, 3 June 1809, 3; Federal Gazette and Baltimore Daily Advertiser, Maryland, 25 September 1812, 3. American & Commercial Daily Advertiser, Baltimore, Maryland, 17 March 1815. Federal Gazette & Baltimore Daily Advertiser, Maryland 19 April 1815, 2.

[49] American & Commercial Daily Advertiser, Baltimore, Maryland, 3 August 1815, 3.

[50] MESDA accession file 4347.2, online: https://mesda.org/item/collections/otho-berry-beall/2564/ (accessed 17 July 2023). Descendants of Mary Berry Beall give her birth date as 1775, however, a written note accompanying a needlework picture by her hand says she completed it in 1792 when she was twelve years old, making her birth date 1780. The later date seems more accurate since she was probably younger than fifty when her third child, Zachariah Berry Beall (1825–1859) was born. Her two other children were William Zachariah Beall (1815–1858) and Washington Jeremiah Beall (1818–1895). See also Effie Gwynn Bowie, Across the Years in Prince George’s County: A Genealogical and Biographical History of Some Prince George’s County, Maryland and Allied Families (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1975), 65-66, online: https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/49019/images/FLHG_AcrsYearsPrinceGeorgesCnty-0097 (accessed 17 July 2023).

[51] Effie Gwynn Bowie, Across the Years in Prince George’s County: A Genealogical and Biographical History of Some Prince George’s County, Maryland and Allied Families (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1975), 65-66, online: https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/49019/images/FLHG_AcrsYearsPrinceGeorgesCnty-0097 (accessed 17 July 2023).

[52] MESDA accession file 4347.3, online: https://mesda.org/item/collections/mary-berry-beall/2565/ (accessed 17 July 2023). Like the portraits of Mary Berry Beall and her husband, a small silk on paper needlework picture depicting a hummingbird in flight descended through the Washington Jeremiah Beal family at Mt. Lubentia. This embroidered picture was worked by Mary Berry Beall when she was a young girl. See MESDA accession file 4347.1, online: https://mesda.org/item/collections/needlework-on-paper/2563/ (accessed 2 October 2023).

[53] 1840 United States Census, Prince Georges, Maryland, 10, online: https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/2183401:8057 (accessed 2 October 2023).

[54] Effie Gwynn Bowie, Across the Years in Prince George’s County: A Genealogical and Biographical History of Some Prince George’s County, Maryland and Allied Families (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1975), 59-60, online: https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/49019/images/FLHG_AcrsYearsPrinceGeorgesCnty-0091 (accessed 18 July 2023).

[55] Washington DC, Wills and Probate Records, 1737–1952, will box 00037, online: https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/104461:9083 (accessed 18 July 2023). Zachariah’s will mentions his sons Thomas, Washington, Jeremiah, and Zachariah, and daughters Elizabeth, Sarah and Mary Beall. His wife was deceased. There are discrepancies in genealogical sources regarding Zachariah’s wife’s name and whether he was twice married. The Archives of Maryland state that he first married Elizabeth Owen (dates unknown) and had the following children: Barbara, Zachariah Jr., Thomas, Jeremiah, and Mary Berry; by his second wife, Mary Williams, he had one son. In his will, Zachariah bequeathed land in various areas of Maryland, Washington, DC, and Kentucky to his children and grandchildren.