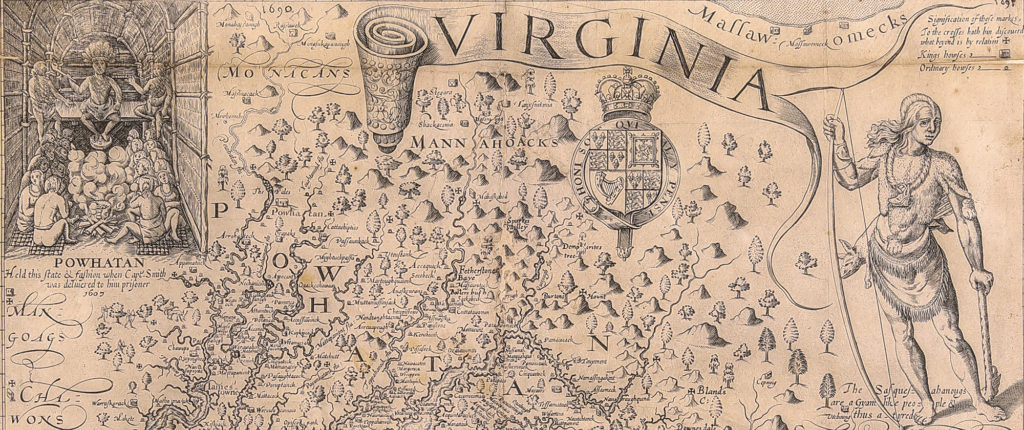

John Smith’s maps of Virginia and New England have stood out as important pieces of colonial American history, particularly as they relate to their distinctive regions (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The maps were first published in 1612 and 1616, respectively. To European cultures, the representations of Powhatan’s village and Virginia’s Algonquin population on Smith’s map of Virginia became symbolic of America’s original inhabitants. Many mapmakers, map-sellers, and booksellers of the seventeenth century and thereafter liberally reproduced images found on the map. Smith’s map of Virginia’s Tidewater region was considered the seminal representation of the colony until John Senex published his map of Virginia in the late seventeenth century (Figure 3). Smith’s chart of New England’s coastline is likewise one of the foundational charts of that region’s cartography.[1] Smith’s map is the first time that “New England” was published in reference to lands north of Virginia. The map was used to promote colonization to the area, and it identified the region as being English, with numerous English place names printed on it.[2]

Smith’s maps of Virginia and New England have been referred to, referenced, pirated, and, since the nineteenth century, published as facsimiles. From their release in the seventeenth century and into the twenty-first century, the impressive accuracy of Smith’s maps have been noted, particularly his map of Virginia, considering the tools and techniques available to the maps’ makers. Today the maps are often used as primary source illustrations by historians because of the archaeological, anthropological, historical, and pictorial information they provide. Scholars of cartography and authorities of early Virginia and New England history are keenly aware of Smith’s work, each map’s popularity, and the number of states in which each was printed.

Aside from academic awareness, do John Smith’s maps serve as emblems of a collective narrative about the founding of Virginia and New England? Do they serve the public memory of those regions, and America in general? According to Stephen Browne, a scholar of rhetoric, public memory is “a shared sense of the past, fashioned from the symbolic resources of community and subject to its particular history, hierarchies, and aspirations.”[3] Jamestown, Pocahontas, Captain John Smith, the Pilgrims, the Mayflower, and Plymouth Rock are all emblematic of America’s founding. Have Smith’s maps of Virginia and New England served a similar role in the past and today?

“Public memory,” as philosopher Edward S. Casey noted, “is often composed in visible space, and ‘ordinary’ people become part of public memory by being publicly noted.”[4] As such this article briefly considers a sampling of the many ways “ordinary” citizens have commemorated the founding of Virginia and New England. A review of the symbols and imagery employed by those celebrations, expositions, and festivals, as well as illustrated in popular books and magazines, will reveal whether or not Smith’s Virginia and New England have indeed become icons of American memory.

Virginia

In 1807 interested citizens from Norfolk, Portsmouth, Petersburg, and Williamsburg gathered to plan for a day of celebration in the hopes of drawing attention to Virginia’s role in the founding of the Republic and to rectify Jamestown’s anonymity in the annals of American history. These citizens planned the Jubilee, as it came to be known, and decided to meet on the thirteenth day of May, the date attributed to the original landing as based on the Julian calendar. The Jamestown Jubilee of 1807 was not promoted beyond advertisements in Virginia newspapers (Figure 4) and by commercial vessels that stopped at Jamestown Island regularly. Word of the celebration spread and over 2,000 participants traveled by water to the island.[5] Subsequent jubilees were held in 1822 and 1834.

During the turbulent 1850s, the Jamestown celebrations were overseen for the first time by citizens from outside the Tidewater. Virginians living in the District of Columbia organized together to create the Jamestown Society, which partnered with the Virginia Historical Society to plan and promote the 250th anniversary celebration that was held on 13 May 1857.[6] The Civil War and Reconstruction prevented any official celebrations at Jamestown Island until the end of the nineteenth century.

Virginians participated in the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, although the exhibits were not historical in nature. Seventeen years later, in 1893, the Association for the Preservation of Virginia (APVA) acquired Jamestown Island and planning began for the Jamestown Ter-Centennial Exposition with financial support from Virginia’s General Assembly.[7] The commonwealth of Virginia—and the United States as a whole—had undergone significant changes since the 250th in 1857: the Civil War, several economic depressions, and the beginnings of the second industrial revolution all changed the nation’s political and economic landscape. For the tercentennial, Virginians were more interested in projecting their economic successes than celebrating the event that marked the beginning of English rule in North America.

The 1907 Jamestown Ter-Centennial Exposition was not held in Jamestown but instead in nearby Norfolk County along the Hampton Roads Channel. The exposition opened on 26 April and closed 30 November 1907. Unlike previous celebrations, the 1907 Ter-Centennial Exposition received much publicity from state and national publications. For example, Town and Country magazine described the location of the celebration as “admirable” with “frontage of two- and one-half miles of historic waters.”[8] The grounds for the exposition embraced about five hundred acres in area and afforded viewers an excellent place to view the naval displays and colonial architecture of exhibition buildings. The area’s historical tourist appeal was emphasized, specifically Hampton Road’s involvement in the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and Civil War. Several other states contributed exhibitions and the exposition’s stated intent was to make the “celebration historical and accurate.”[9]

The Ter-Centennial Exposition was an “international naval, marine and military celebration that included historical, educational, and industrial exhibitions.”[10] Most of the exhibitions were not historical but instead closely resembled previous state expositions that touted a region’s economic and educational development, advancements in art and science, and flourishing commercial industries. Numerous national magazines, journals, and newspapers reported on the exposition, and the fair was promoted nationally. The best-known advertisement for it was a bird’s eye view of the Hampton Roads area published by A. Hoen and Company titled Jamestown Ter-Centennial Exposition/Historical, Educational, Naval, Military, Industrial/Commemorating the 300th Anniversary of the First Permanent English Settlement in America/Located on Hampton Roads close to Norfolk, Portsmouth, Newport News, Hampton and Fortress Monroe / Opens April 26, 1907, General Offices: Norfolk, Virginia. Closes Nov. 30, 1907 (Figure 5). Magazines like Town and Country and Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature published this view to accompany articles promoting the exposition.[11]

As the Ter-Centennial Exposition was promoted through magazines that had a national readership, articles were written to cater to general audience. Some articles explored the roles of Pocahontas and John Smith at Jamestown (Figure 6). None of those publications are known to have included John Smith’s map of Virginia. For example, Jane Stewart, who wrote for the New York Observer and Chronicle, described the different exhibitions and especially focused on the Library of Congress’s exhibit that included maps and manuscript materials.[12]

The Library of Congress’s exhibit at the 1907 Ter-Centennial marks the first time that John Smith’s map Virginia is documented as being part of a celebration of Jamestown’s founding. The map was displayed in Government Building A alongside other rare maps to show the development of Virginia. The other maps exhibited included wall maps and charts to show the location of Indian tribes, expansion, settlement, and data related to the colonial period and the Civil War.

In contrast, Virginia’s own exhibition, designed and curated by State Librarian James P. Kennedy, did not display Smith’s map of Virginia. Kennedy was commissioned to oversee the planning and creation of the exhibit and given the power to negotiate loans for archival material as needed for the event.[13] The rare books, maps, portraits, and manuscripts displayed were borrowed from the Virginia State Library’s and the Virginia Historical Society’s collections.[14] The map collection was displayed in the annex to the main Virginia exhibition and Kennedy purposely wanted to show “many interesting maps of the earliest period of our [Virginia’s] history.”[15] The historical maps were complemented by a series of population maps that showed westward expansion. The Virginia State Library report for the Ter-Centennial Exposition lists the maps shown and indicates that they were all reproductions. Again, Smith’s Virginia was conspicuously absent.[16] The list of maps includes the following:[17]

-

-

- DeBry-White map of Virginia published in 1585

- Jansson’s map of Virginia and Florida dated 1630

- Blaue’s map of Virginia dated 1667

- Augustine Herrman’s map of Virginia and Maryland, 1670

- Mortier’s Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and East and West New Jersey

- Senex’s Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New York, 1719

- Pierre Vander’s Virginia, 1729

- Robert de Vaugondy’s Virginia and Maryland, 1755

- Homann’s Virginia, Maryland and Carolina, 1759

- Fry-Jefferson Map of Virginia, 1775

- Hinton’s Virginia

-

The 1907 Ter-Centennial exposition also included exhibitions from several New England states. The only three that included maps in their exhibits were Vermont, New York, and Massachusetts. Unsurprisingly, none were recorded as including John Smith’s map of New England.[18] Interestingly, the Colonial Dames of Massachusetts were responsible for collecting items for that state’s exhibit, and a large map of Virginia, dated 1781, and a chart of the coast were included. Unfortunately, the title of that map was not published in their report on the Ter-Centennial.[19]

New England

Since the 1790s New Englanders had gathered yearly to commemorate Pilgrims Day, a day set aside to remember the Pilgrim’s landing at Plymouth in 1620 with special emphasis placed on New England’s role in the development of the American Republic. Another important celebration to emerge in New England to celebrate the landing of the Pilgrims was Forefather’s Day.[20] Each commemoration was marked by speeches, dinners, and poetry readings. As the nineteenth century progressed, Plymouth Rock, the Mayflower Compact, and even the Pilgrims themselves became iconic representations of New England and American memory. In 1820 the Pilgrim Society was established. The society raised money to build Pilgrim Hall, which opened in 1824, making the town of Plymouth an early American tourist destination.

One hundred years later, planning for the Pilgrim Tercentenary of 1920-1921 began during the First World War. The committee planning the celebration decided not to host an exposition but to focus their efforts on restoring Plymouth Rock, improving Coles Hill, hosting a pageant during the summer of 1921, supporting the dedication of monuments and other structures related to the Pilgrim landing, and erecting markers at historic sites (Figure 7 and 8).[21] The principal celebrations were held in the summer of 1921. There was an exhibition displayed in Pilgrim Hall, but no mention was made of Smith’s New England, his pamphlet, or his survey of the coastline.[22]

The American publishing industry showed its support by producing numerous articles and books related to the 1620 Pilgrim landing, including juvenile literature such as A Mayflower Maid by E.A. and A.A. Knipe ( The Century Company) and The Young Pilgrims by Charles Herbert ( The Lippincott Company) (Figure 9)[23] Advertised adult fiction and nonfiction included The Old Coast Road by Agnes Edwards; In the Days of the Pilgrim Fathers by Mary Caroline Crawford; Young Peoples History of the Pilgrims by William Elliot Griffis; The Women Who Came in the Mayflower by Annie Russell Marble; The Last of the Mayflower by Rendel Harris; The Argonauts of Faith by Basil Mathews; The Story of the Pilgrim Fathers by H.G. Tunnicliff; A Pilgrim Maid by Marion Ames Taggart; and A Loiterer in New England by Helen W. Henderson. Mr. Byron Barnes Horton of Sheffield, Pennsylvania worked on a bibliography of Pilgrims of Plymouth that was to be published in 1920.[24] Although Smith’s map of New England was not used as a promotional piece to advance and publicize the Tercentennial, George H. Boughton’s painting “Puritans Going to Church” appeared in numerous publications (Figure 10). The work shows a small company of early New England settlers marching through the snow to church led by their minister and accompanied by men in arms. Ironically, the painting better reflects the era of King Philip’s War than the era of the Pilgrim’s settlement at Plymouth.[25]

As part of an effort to encourage local support for the Pilgrim Tercentennial, the Massachusetts Department of Education published materials that provided teachers with classroom curriculum that included program materials, suggestions for pageants, and reading materials. Students could make scrapbooks about the Pilgrims and trips to Plymouth could be made by graduating classes. The materials produced included a bibliography of reliable sources. John Smith was included on page 57 of the bibliography, noted for having explored New England and naming Plymouth on his chart of New England.[26]

The year 1921 also saw a number of major libraries and museums throughout the United States hold exhibitions to celebrate the Pilgrims. The Detroit Institute of Art hosted an exhibition that included textiles, furniture, silverware, household wares, weapons, plates, dishes, clothes, samplers, portraits, and rare books. Maps were not displayed.[27] The New York Public Library produced an exhibition titled The Pilgrim Tercentenary Exhibition in the New York Public Library. It was held in the main exhibition hall and included “books, pictures, personalia, maps, views, commemoration and celebration orations, medals, cards, programs, etc., relating to the Mayflower Pilgrims in their homes and haunts in England, Holland and America down through the entire period during which Plymouth Colony existed as a separate body politic.”[28] According to Victor Hugo Paltsits this exhibition “sharply differentiates the Pilgrims from the more extensive and better known Puritan Commonwealth of Massachusetts Bay.”[29] The exhibit spent a great deal of space representing Pilgrims in New England before and after colonization. John Smith’s tract A Description of New England and his map titled New England were displayed. Smith’s works were presented in a context of how they related to the Pilgrim landing and the exhibition labels emphasized Smith’s influence, in general, on English settlement in New England. Paltsits wrote “his work really constitutes a group of factors in Pilgrim [New England] history.”[30]

To date, the Pilgrim Tercentenary was the last true national and regional celebration of the events of 1620.

Virginia Redux

By the early 1950s plans were once again being made to celebrate the first permanent English settlement in North America. In contrast to 1907, when the focus of celebration was on Virginia’s economic growth and potential, the planners of the 350th anniversary jubilee intended to commemorate the history of Jamestown Island. Federal and state support were secured to highlight the roles of Jamestown, Yorktown, and Williamsburg in colonial and national American history. Plans were made to complete the Colonial Parkway, a highway that connected Yorktown, Williamsburg, and Jamestown, to re-create the 1607 Jamestown settlement by Jamestown Island, and to build a visitor’s center on the site.

Of most significance to our discussion of John Smith’s maps, it was during the 1957 celebration that his map of Virginia became an icon of American memory. The Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission meticulously selected symbols and images to represent the festival. Those symbols were widely used by local businesses and newspapers as well as various organizations to show their support for the program. Details from Smith’s Virginia were not selected by the commission because images easily reproduced in promotional materials were preferred; however, Smith’s map of Virginia was published in newspapers, discussed in scholarly works, and was the inspiration for an exhibition at the 1957 Jamestown Festival.

As would be expected, local newspapers published numerous articles and special editions about the Virginia 350th Anniversary Festival. Of note, there were articles published specifically regarding Smith’s Virginia. For example, the Richmond Times Dispatch included a Jamestown Festival section that opened with a large illustration based on the Smith map of Virginia.[31] Richmond printers Whittet and Shepperson produced the Jamestown Festival Official Program. Smith’s Virginia was included as an illustration in the program, accompanied by text about Smith’s leadership and literary and cartographic accomplishments. Smith’s map of New England and his contributions to that region were also acknowledged in the program.[32] By including Smith’s New England and his contributions to the development of that region, the Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission chose to acknowledge New England and its role in American history rather than take an adversarial stance to challenge the pilgrims, Plymouth Rock, and the Mayflower’s status as iconic to our nation’s memory.

The 1957 Jamestown celebration inspired many books. Edward M. Riley, director of research for Colonial Williamsburg, was hired to organize the festival’s archival and historical consultants.[33] Riley decided to make research completed on seventeenth century Virginia history available and to provide “something in print that would inform the tourist and be also of permanent reference value.”[34] This included the twenty-three historical booklets edited under the supervision of Dr. Earl G. Swem, librarian for the College of William and Mary. The third book in the series, authored by Ben C. McCary, was titled John Smith’s Map of Virginia with A Brief Account of Its History and provides a synopsis of Smith’s Chesapeake voyages and an analysis of the map’s ten states. Several journals also published issues devoted to the festival, including the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, The William and Mary Quarterly, and Virginia Cavalcade. Institutions such as the Library of Congress hosted exhibitions, including one titled “The 350th Anniversary Settlement of Jamestown” that displayed Smith’s map of Virginia and his book The Generall Historie of Virginia. The Library of Congress, with the Verner W. Clapp Publication Fund, printed a limited run of facsimile copies of Smith’s map of Virginia for distribution and sale to the public.[35] The Huntington Library, the John Carter Brown Library, Princeton University Library, the Mariner’s Museum, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the Virginia State Library, Alderman Library at the University of Virginia, the College of William and Mary Library, the Valentine Museum, and the Richmond Academy of Medicine also opened exhibitions related to the 1607 Jamestown Settlement.[36]

As part of the exhibition space at Jamestown Festival Park the organizers created the Old and New World pavilions to “house the British and American exhibits” and to best “orient visitors with the British background settlement and of American achievement which grew out of that settlement.”[37] The British exhibit titled “Old World Heritage” emphasized the common ideals between Great Britain and the United States. Priceless artifacts from England were displayed. Of specific note, the British government loaned a copy of John Smith’s Virginia owned by the Duke of Devonshire and the Trustees of the Chatsworth Settlement.[38] “Old World Heritage” was connected to the New World Pavilion where the “New World Achievement” exhibition was placed.

“New World Achievement” was presented in two sections; the first emphasized the early colonial period and the second focused on the contributions made by Virginians in the New World. The commission worked with many museums, archives, libraries, colleges and universities, and private owners to compile the exhibitions.[39] Several items were loaned to the Commonwealth of Virginia for the exhibition. The Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission loaned a photographic reproduction of John Smith’s map of Virginia to the exhibition, as well as a reproduction of a letter from John Smith.[40] The commission decided to rebuild the Jamestown fort. With the assistance of experts such as Professor Ben McCary, Powhatan’s lodge was also reconstructed. Dr. McCary “provided information for its design and construction, which follows closely the depiction in John Smith’s map and the descriptions provided by period writers.”[41]

Fifty years later, Jamestown 2007 celebrated the quadricentennial of Virginia’s founding. The events and exhibitions of Jamestown 2007 brought John Smith and his maps into the national spotlight once again. Virginia was used to promote Jamestown 2007, exhibited during the festival, and has been discussed, analyzed, and debated by historical and cartographic scholars over the years. Smith’s map of Virginia has proven to be a source of curiosity and intrigue for researchers and map connoisseurs alike, who continue to learn from it.

Conclusion

This brief review of the imagery and artifacts employed by expositions commemorating the founding of Virginia and New England, as well associated newspapers and other printed materials, reveals that it was not until the second half of the twentieth century that John Smith’s Virginia became an icon of Virginia and American memory. Smith’s map of New England is still used, referenced, and discussed by historians and cartographic scholars, but it has never achieved the same iconic status in regional or national memory as Smith’s map of Virginia.

Several factors may explain why Smith’s New England did not become iconic for the region. First, unlike Smith’s map of Virginia, New England is not a “mother” map, a map from which several derivative publications are based. Second, even though John Smith’s map was the first to give the region north of Virginia its now-familiar regional name, New England, the appellation was not fully accepted until the second half of the seventeenth century.[42] Third, the map of New England was not widely circulated, and only those interested in New World colonization would have shown the map any attention. Fourth, map scholars have pointedly discussed the numerous, and currently used, English toponyms on Smith’s chart, but cartographic historian Matthew Edney points out that the placenames were not adopted by the English prior to colonization but instead, and coincidentally, only through the passage of time.[43]

Perhaps the most significant reason for Smith’s New England not becoming a “mother map” is because it is not a true sea chart. The coastline is defined correctly but many key details are left out, including numerous inlets and shoal depths. The purpose of Smith’s voyage to New England was commercial in nature and sponsored by the Northern Virginia Company. Smith’s instructions for this particular voyage north were to 1) hunt for whales, 2) look for gold and silver mines, and 3) catch fish and trade furs with Native Americans if the hunt for whales and the search for gold and silver mines were unsuccessful.[44] Unlike his time in Virginia, Smith was not afforded the time to properly survey the coastline because of his preassigned duties. His time along the coastline was short: six weeks at most. His resulting map of New England is really a reconnaissance of the region’s coastline and not a complete work. Because it does not include a great amount of detail about coastal features and shoal depths, the map was not useful to those sailing in the region. And due to the dearth of information about inland topography, Smith’s map was of little value to European colonists looking to settle New England’s interior.

As Edney observes, Smith’s New England was for landlubbers, merchants, and other proprietors interested in colonial settlement.[45] It became just another historical chart of New England. Virginia, however, was the source for a number of later maps of Virginia and the American South. Although it would take nearly three and half centuries, Virginia eventually did become iconic to Virginia memory. The economic prosperity that came to the Virginia Tidewater in the twentieth century certainly contributed to the historical and archaeological interest in the region. The popularity and success of Colonial Williamsburg only bolstered the historic image of the region. And the Virginia 350th Anniversary in 1957 solidified Smith’s map of Virginia as an iconic feature of Virginia’s identity and earliest memory.

Cassandra Farrell is Sr. Map Archivist at the Library of Virginia and a doctoral student in history at George Mason University. She can be contacted at [email protected].

[1] John Smith, New England: most remarqueable parts thus named by the high and mighty Prince Charles, prince of great Britaine (London: Printed by Geor. Lowe, [1616]), Boston Public Library, https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:3f462s698.

[2] Joseph A. Conforti, Imagining New England: Exploration of Regional Identity from the Pilgrims to the Mid-Twentieth Century, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001)11-17. Pilgrims and Puritans were inheritors of the name New England, a name given to the region by Captain John Smith. Smith had explored the New England coastline in 1614 and viewed the region as an extension of England. He published his description in 1616 and the name Virginia was supplanted by the name/phrase “New England.” His map definitely portrayed the region as an English annex. English place names, instead of Indigenous Native American names were printed on the map and Smith spent the rest of his career promoting the colonization of New England. In fact, Smith supported Puritan migration to the New World- he had been in correspondence/contact with John Winthrop-and the Puritans seemed to support Smith’s view that their colony was an extension of England. This view wasn’t supported by the Pilgrims. If they were in any way influenced by his writings, it is not clear.

[3] Stephen Browne, “Reading, Rhetoric, and the Texture of Public Memory,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 81, no. 2 (1995): 248.

[4] Edward S. Casey, “Public Memory in Place and Time,” in Framing Public Memory, edited by Kendal Phillips (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama, 2004), 19.

[5] “National Jubilee,” The American Gleaner and Virginia Magazine 1, Issue 10 (30 May 1807): 155. For more information about the 1804 and subsequent celebrations please see Kiracofe’s “The Jamestown Jubilees: State Patriotism and Virginia Identity in the Early Nineteenth Century.” On page 8 of his report, M’Laughlin describes how yards of the original palisade are still seen at low tide at least 150 or 200 paces from the shore, and the island has sustained great loss on the south side and more considerable on the west side. A tiny sliver of land still connects Jamestown with the mainland, but it was clear that it would not be long before Jamestown was to be an island.

[6] Ralph Hardee Rives, “The Jamestown Celebration of 1857,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 66, No. 3, (July 1958): 259-260.

[7] J.S. Ingram, The Centennial Exposition (Philadelphia: Hubbard Bros., 1876). See Publishers’ Weekly issues for 1 July 1876, 29 July 1876, 16 September 1876, and 7 October 1876 for further information about maps displayed at the 1876 Centennial; see W.D. Howell’s article “A Sennight of the Centennial” for more information about the Massachusetts exhibit. This was published in the July 1876 Atlantic Monthly on page 101.

[8] “The Coming Exposition at Jamestown: Education, Science, Industry, Commerce and Social Progress to be Splendidly Shown: Naval and Military Features Prominent, ” 1907 Town and Country (Feb 02, 1907): 12 https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.virginiamemory.com/docview/126853904?accountid=44788

[9] Carol Abbott, “Norfolk in the New Century: The Jamestown Exposition and Urban Boosterism,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 85, no. 1 (January 1977): 92.

[10] “The Coming Exposition at Jamestown,” Town and Country (February 2, 1907): 1, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.virginiamemory.com/docview/126853904?accountid=44788

[11] Ibid. This same bird’s-eye view is seen in other magazines from 1907 and is included in the Blue Book and seen as a representation of the exposition, a symbol of the 1907 expo; See: “Naval and Military Features Prominent,” Town and Country, February 2, 1907; Charles Frederick Stansbury, “The Jamestown Exposition,” Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature 148 (March 2, 1907: 273-280); Please see the front cover of The Illustrated History of the Jamestown Exposition published by the Hampton Roads Naval Museum in 1990. *Interestingly, a bird’s-eye view of Philadelphia, including Centennial Exhibition grounds was published in 1876. So, it was not uncommon to use a bird’s-eye view to represent a locality for a major international event. See “Philadelphia,” Harper’s Weekly, (May 27, 1876): 433.

[12] “The Jamestown Exposition and the Event Which It Commemorates,” The American Antiquarian and Oriental Journal 28, no. 6: 325-330, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.virginiamemory.com/docview/89621226?accountid=44788; Jane A. Stewart, “The Jamestown Exposition: Three Centuries of Progress to be Shown,” New York Observer and Chronicle, (1833-1912), 25 Apr, 544, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.virginiamemory.com/docview/136285684?accountid=44788; John T. Maginnis, “Opening of the Jamestown Exposition,” Scientific American (1845-1908), Apr 27, 351-353. https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.virginiamemory.com/docview/126807414?accountid=44788.

[13] Governor Claude Swanson to The President, 4 October 1906, Correspondence and Subject Files of the Librarian of Virginia, Box 139, Folder 1, Accession 28078, State Government Records Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[14] Kennedy to Wm. A. Anderson, 10 June 1906, Correspondence and Subject Files of the Librarian of Virginia, Box One, Folder One, Accession 28078, State Government Records Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA. This letter indicates that the General Assembly requested that the state library “make an exhibition of such books, portraits, manuscripts, or other state possessions entrusted to their keeping at the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition. In making this request it is understood that the exhibit will be placed in one of the fireproof buildings of the Exposition set apart for such purpose.” And Kennedy requested that the state library be able to determine how much room it needed in the exhibition hall before other states were allotted space in the building.

[15]Kennedy to Hon. J. Taylor Ellyson, 11 May 1906, Correspondence and Subject Files of the Librarian of Virginia, Box 40, Folder 1, Accession 28078. State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[16] The Library of Virginia did not have an unbound copy of the Smith map until the late 1990s and today’s records at the Virginia Historical Society indicate that their collection did not include an unbound copy per telephone conversation with VHS staff on Friday, 27 February 2015. Both collections have rare books that include or have included states of Smith’s maps.

[17] Fourth Annual Report of the Library Board of the Virginia State Library 1906-1907 to which is Appended the Fourth Annual Report of the State Librarian, (Richmond: Davis Bottom, Superintendent of Public Printing, 1907), 101. (Eckenrode worked with William Stanard of the Virginia Historical Society to set up this exhibition. Torrence compiled title pages from early books of Virginia for display). A letter dated 1 April 1907 from Kennedy to B.S. Hume lists the insurance appraisal for Library materials exhibited at the exposition. Fourteen maps are listed, and this seems to indicate that the reproductions were from the state library’s collections, see Kennedy to Mr. B.S. Hume, 1 April 1907, Correspondence and Subject Files of the Librarian of Virginia, Box 55, Folder 8, Accession 28078, State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[18] The Massachusetts exhibition included silver, miniatures, rare books, and manuscripts. For more information see The Official Blue Book of the Jamestown Ter-Centennial Exposition (Norfolk, Va.: The Colonial Publishing Company, 1909), 519-522. The New York State exhibit at Jamestown included several maps; see Cuyler Reynolds, New York State Historical Exhibit at the Jamestown Exposition, 1907 (Albany: J.B. Lyons Company, State Printers, 1907) for more information. The New York State exhibit did include Captain John Smith’s journal. The Rhode Island exhibit included maps; see Rhode Island Jamestown Ter-Centennial Exposition Committee report for more information, Report of the Jamestown Ter-Centennial Exposition Committee Made to the General Assembly at its January Session, 1908 (Providence, Rhode Island: E.L. Freeman Company, State Printers, 1908).

[19] The Massachusetts Colonial Loan Exhibit at the Jamestown Ter-Centennial Exposition, Boston: Wright and Potter Printing Co., 1907.

[20] David J. Kiracofe, “The Jamestown Jubilees: State Patriotism and Virginia Identity in the Early Nineteenth Century,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 110, no. 1, (2002): 43-44.

[21] Joseph Walsh, “Pilgrim Tercentenary Celebration,” session vol. 2, 28 February 1920, H. Report 691, serial V7653, 1-3.

[22] H. Whitfeld, ed., Mother Plymouth: A Souvenir of the Mayflower Tercentenary, Together with the Story of the Pilgrim Fathers, 1620-1920 (Devenport: Whitfield and Newman, 1920).

[23] “The Tercentennial of the Mayflower,” The Methodist Review 36 (Nov. 1920): 6; William Elliot Griffis, “What the Pilgrim Fathers Accomplished,” The North American Review 213 (January 1921): 782; Sidonie Matzner Gruenberg, “The Book Table: Devoted to Books and their Makers: Children’s Reading”, Outlook (24 November 1920): 557.

[24] “Notes for Bibliophiles,” The Dial: A Semi-monthly Journal of Literary Criticism, Discussion and Information 62 (11 January 1917): 7.

[25] A.W. Abrams, “Puritans Going to Church,” Outlook (8 December 1920): 639, https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.virginiamemory.com/docview/136994403?accountid=44788.

[26] Prepared by the Special Committee on the School Observance of the Pilgrim Tercentenary, The Pilgrim Tercentenary 1620-1920: Suggestions for Observance in the Schools, Giving Specific Programs, Pilgrim Stories, a Pageant and a Bibliography, The Commonwealth of Massachusetts Bulletin of the Department of Education (Boston: Wright and Potter Printing Co., 1920), 33. The quote is… “Of all the parts of the world I have yet seen not inhabited I would rather live here than anywhere.”

[27] Detroit Institute of Arts, “Catalog of the Pilgrim Tercentenary Exhibition,” (Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 1921), https://archive.org/details/catalogofpilgrim00detr/page/n2.

[28] Victor Hugo Paltsits, The Pilgrim Tercentenary Exhibition in the New York Public Library (New York: Printed at the New York Public Library, 1921), 1

[29] Paltsits, Pilgrim Tercentenary Exhibition, 1.

[30] Paltsits, Pilgrim Tercentenary Exhibition, 3.

[31] Box 33, Accession 25869, Records of the Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission, 1953-1958, State Government Records Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA.

[32] The Jamestown Official Program (Richmond: Whittet and Shepperson, 1957), 9.

[33] Lyman H. Butterfield of the Institute of Early American History and Culture in Williamsburg was the original organizer of the 1957 festivals archival and historical consultants. He resigned and was replaced by Riley. Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission, Report Jamestown Festival, 71.

[34]Jamestown-Williamsburg-Yorktown Celebration Commission, The 350th Anniversary of Jamestown 1607-1957: Final Report to the President and Congress of the Jamestown-Williamsburg-Yorktown Celebration Commission (Washington D.C., 1958), 107.

[35] United States. Jamestown-Williamsburg-Yorktown Celebration Commission, 350th Anniversary of Jamestown, 117.

[36] Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission Report Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission, 81-82.

[37] Report of the Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission, House Document No. 32 (Commonwealth of Virginia Division of Purchase and Printing, Richmond, 1958), 29.

[38]Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission, Report Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission, 210.

[39] Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission, Report Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission, 31.

[40] Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission, Report Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission, 213.

[41] Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission, Report of the Virginia 350th Anniversary Commission, 33.

[42] See Matthew Edney, “A Cautionary Historiography of John Smith’s New England,” Cartographica 46, issue 1, 1-27.

[43] Edney, “Cautionary Historiography,” 1-27; Matthew Edney, “The Anglophone Toponyms Associated with John Smith’s Description and Map of New England,” Names: A Journal of Onomastics 57, no. 4 (December 2009):189-207.

[44] Jeannette Black, “Mapping the English Colonies in North America: The Beginnings,” The Compleat Plattmaker: Essays on Chart, Map and Globe Making in England in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, Ed. Norman J.W. Thrower (Berkeley: University of California Press), 101-125.

[45] Edney, “Cautionary Tale,” 1-27.

![Fig. 2: "New England" by John Smith (cartographer), Simon Passaeus (engraver), George Low (printer); London, England; [1624]. Ink on paper; HOA: 30 cm, WOA: 36 cm. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center. https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:3f462s64w (accessed 6 June 2023).](https://www.mesdajournal.org/files/CFarrell_Fig_02_Thumb.jpg)

![Fig. 3: "A New Map of Virginia. . ." by John Senex (cartographer); London, England; 1721. Ink on paper; HOA: 49 cm, WOA: 54 cm. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, Map Div. 97-6264 [LHS 37], The New York Public Library. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-eeed-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (accessed 6 June 2023).](https://www.mesdajournal.org/files/CFarrell_Fig_03_Thumb.jpg)