|

In 1846 the city of Washington mourned John McLeod, a man who for more than thirty-five years had operated a series of four successful schools that grew in both popularity and size over the course of his life. Halfway through his career, in 1822 he could accommodate around 300 boys and girls at his Central Academy and was said to have “done more by his system of education for the rising generation than any other man who ever resided among us.”[1] Two years before his death, McLeod reflected on his long and successful career stating that “It will be thirty-six years this day, the 10th of May, since I opened at the Navy Yard with only four scholars. [Since then] I have had some thousands under my care.”[2] Later in his life he boasted to have taught “more pupils than any other teacher in the Union.”[3] However, it was not only the number of students he taught that made him prolific, his longevity was also unrivaled. In 1827 he reflected that “there were thirty teachers here when I commenced – all have deserted the employment long ago.”[4]

McLeod’s outspoken philosophies on teaching included educating boys and girls of all classes, providing free education for mechanics’ (or craftsmen’s) children, and offering needlework instruction to his female students at no additional charge.[5] His goals were ambitious. In 1822 at the opening of his new and spacious Female Central Academy he stated,

“The plan of instruction that will be adopted has never been attempted here. It will ensure success and will afford the citizens of this District an opportunity of having their daughters instructed in these useful and ornamental branches of education, which will qualify them to discharge their duty, in any situation where fortune may cast their lots, with credit to themselves and advantage to their beloved country.”[6]

He noted that his plan would ensure that “any young lady of common talents may, by employing her time well, become well acquainted with all the useful and ornamental branches taught here.”[7] Instruction in the female department at Central Academy included “spelling, reading, writing, arithmetic, the English language grammatically, with composition, Geography, with the use of maps and globes, History and the French language, painting, Drawing, music, Dancing, plain and ornamental Needlework, knitting, millinery and mantua-making.”[8] The plan of instruction that McLeod adopted included the astounding offer that (Figure 1):

“Mechanics of every description may have their sons and daughters educated at this establishment without paying money. Trade will be taken from brickmakers, bricklayers, blacksmiths, silversmiths, tinners, cabinet makers, chair makers, bookbinders, butchers, bakers, weavers, tailors, shoemakers, hatters, chandlers, &c. Also, lumber and wood merchants, and merchants of every description, will be dealt with as liberally as circumstances will permit.”[9]

However, he added, “Clerks and clergy, doctors and lawyers, will, of course, be ready at all times to pay cash.”[10]

As John’s own testimony suggests, his schools were large and employed a staff of teachers that oversaw the day-to-day education of their students. Logically, a school that existed for nearly four decades, educated thousands of students, and offered free education to children whose families were of the tradesman class as well as free needlework education to female students must have surviving examples of the needlework stitched at McLeod’s school.

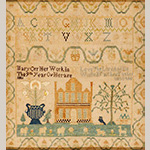

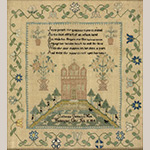

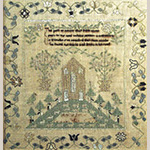

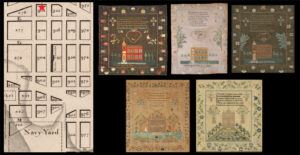

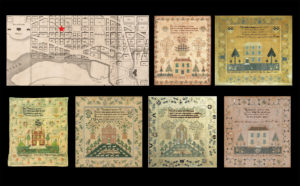

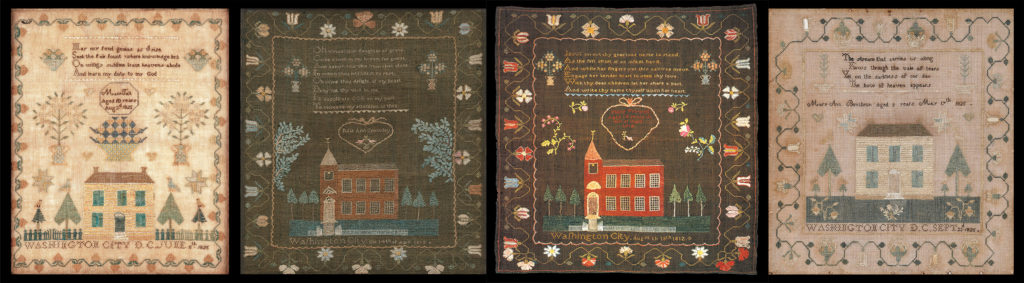

In 2019 the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts acquired a needlework sampler worked by Mary Tait dated 11 June 1825 (Figure 2). This needlework is prominently featured on the cover of Gloria Seaman Allen’s publication Columbia’s Daughters: Girlhood Embroidery from the District of Columbia (Figure 3).[11] Mary’s sampler is part of an impressive group of southern samplers referred to as the Navy Yard Group. Stitched between 1810 and 1842, there are currently fourteen documented examples that form this group of needlework.

Mary Tait (1815-1891) was born in Glenholm, County of Peebles, Scotland, on 3 August 1815 to Alexander Tait (1780-1848) and his wife Jane Affleck Tait (1787-1874).[12] The family immigrated to Washington, DC, in 1817, and by 1822 Alexander was listed in the city directory as a stonecutter living under the shadow of the rising Capitol Building.[13]

Mary Tait’s family was deeply involved in the construction of Washington, DC. Following in his father’s footsteps, Mary’s brother, James A. Tait (c. 1814-1895) was superintendent of stonework for the construction of the Treasury Building, as well as the inspector and receiver of materials for the US Capitol under its supervising engineer, General Montgomery C. Meigs.[14] In 1841, Mary wed Donald Stewart (1809-1855) a Scottish stonemason like her father and brother.[15] After Donald’s death, the industrious Mary provided for her five children and elderly mother by keeping a “fancy store” in the District of Columbia.[16]

Mary completed her “Washington City, D.C.” sampler in June of 1825, shortly before her tenth birthday. Her brother James’s obituary provides a tantalizing clue as to the school where Mary’s sampler might have been made. It notes that James attended “McCloud’s Academy,” a clear reference to John McLeod, whose Central Academy was located between the Capitol and President’s House, ten blocks from the Tait household.[17] Given the proximity to the Tait family, it is likely that a free and valuable education for stonecutters’ children would have been too attractive to pass up.

DISCOVERING THE NAVY YARD SAMPLER GROUP

In 1975 the curator of the DAR Museum, Elisabeth Garrett, published an article in The Magazine ANTIQUES about samplers in their collection. In her article she called attention to the samplers worked by Martha Ensey (Figure 4) and Julia Ann Crowley (Figure 5), both completed in 1813. Garrett observed that these samplers were “nearly identical” and that the sampler makers both lived near the bridge at the Washington Navy Yard. She added that the steepled four-bay brick building with its pedimented doorway, bell, and weathervane suggests that the building is a schoolhouse rather than a church and may have been the school the girls attended.[18] With this publication, Garrett started the pursuit of what was to be known as the Washington Navy Yard Sampler Group.

Almost twenty years later, in 1993 Betty Ring listed the group as the “Samplers of Washington City” in her two-volume book Girlhood Embroidery.[19] She expanded the group with her addition of four more samplers stitched between 1810 and 1813: those stitched by Maria Boswell (Figure 6), Julia O’Brien (Figure 7), Charlotte Clubb (Figure 8), and most intriguingly, yet another sampler stitched by the same Julia Ann Crowley mentioned above (Figure 9). Crowley’s 1810 work is the earliest in the group and the only one that features the inscription “Washington Navy Yard” (the others all say “Washington City”). While no instructor was identified, Ring suggested the teacher responsible for this group may have had ties to Philadelphia because the composition and border resembled samplers from that area.[20]

The foremost expert on this group was Gloria Seaman Allen who was a noted authority on samplers and female education in the Chesapeake and District of Columbia regions. She devoted an entire chapter in her book, Columbia’s Daughters, to this group of samplers.[21] Published in 2012, the book even significantly featured one of these samplers on its cover. Allen’s research expanded the group to include thirteen samplers, falling within three time frames that extended from 1810 to 1842. As each period displayed distinct styles, she suggested that this pointed to the possibility that different teachers were responsible for each of the three sub-groupings. She added that, remarkably, all thirteen samplers are distinct from samplers stitched in neighboring localities of DC and suggested a community identity which is captured in this group.[22] Columbia’s Daughters provided further in-depth discussion of schools and teachers who could possibly have been responsible for this group, which Allen renamed the “Navy Yard Architectural Samplers.”[23]

Previously unpublished, a fourteenth sampler that fits this group has recently been identified. Appearing at Brunk Auctions in February 2023, the Mary Ann Bonthron sampler (Figure 10) shares not only stylistic characteristics with other samplers from the group, but Mary Ann Bonthron herself also shares similar family demographics that characterize many of the other sampler makers’ backgrounds – she was the daughter of Scottish stonemason John Bonthron and her family was part of the mechanic or craftsman class.[24] The discovery of this sampler builds on current research and its visual characteristics solidifies its place within this group. As the group continues to grow, it is extraordinary to have such a large body of work without a clear identification of the educational institution behind it.

With the discovery of this new sampler, it seems appropriate to take another look at the grouping and further develop the story introduced by Garrett, Ring, and Allen, particularly as intriguing questions remain unanswered. Elizabeth Garret put forward the hypothesis that the brick building with the bell tower might be an actual school; this is an intriguing proposition and begs the question, if so, what school does it represent? A sampler dated 1810 specifically identifies the Washington Navy Yard – what inspired this addition and why this distinction? The visual evidence from the samplers themselves makes the connection to Philadelphia likely, but how did that connection come to be a part of these samplers? What or who could be responsible for the Philadelphia, and broadly Pennsylvanian, influence? For a school that was in operation for over thirty-five years there is a remarkable level of consistency in the visual language displayed on the samplers. This begs the question, how is it possible for there to be what Allen termed a “community identity” during a period when various teachers taught at the school? Finally, and most intriguingly, what can explain the large percentage of surviving samplers whose makers’ fathers were from the mechanic class?

Understanding this sampler group within its historical context paints a fascinating picture that resonates with the larger American story. In the early 1800s female education began to flourish in the new nation, and Washington City, now known to us as Washington, DC, proved to be a prime environment to support schools and female seminaries; there were numerous academies and teachers operating in the Capital in the early nineteenth century.[25] Among other candidates identified by Allen, McLeod’s school surfaced as a possible source for the Navy Yard samplers. Further research has revealed his school influenced not only the surrounding community but introduced a new and innovative democratic educational approach that asserted “terms suited to the times and to all classes of the community.”[26]

JOHN McLEOD (c. 1766-1846)

Remembered in the Centennial History of Washington as “the most prominent and peculiar of the earlier teachers in Washington,” McLeod ran his school under the motto “Order is Heaven’s First Law” which he made material in a large sign over the door of his schoolhouse, visible to all his students as they entered.”[27]

Born in Ireland around 1766, John McLeod was educated for a life in the ministry; however, he chose to immigrate to America, where he established himself as a teacher.[28] Information on McLeod’s early career in education has been elusive, yet we know he was living, and presumably working, in Baltimore in 1804 when he married Rebecca Coulson on New Year’s Eve.[29] One account describes McLeod’s bride as one of his former pupils, but it is more likely that the twenty-six-year-old Rebecca was a fellow teacher working in Baltimore.[30]

Rebecca Coulson (1778-1858) was born to William Coulson (1746-1794) and Rhoda Kerr Coulson (b. 1747) in 1778 in Adams County, Pennsylvania; however, by 1780, the family was established in neighboring York County to the east. [31] Rebecca’s role in her husband’s schools has not been made clear. However, it was customary for wives to assist their husbands in their schools, particularly in the female branches of education, and it is likely she served this role, possibly bringing with her the Philadelphia and Pennsylvania influence seen in many of the samplers from this school.[32]

In 1807 John and Rebecca traveled to the nation’s young Capital. Early accounts describe Washington City as consisting of “four classes of people, whose pursuits, interests and manners differ as widely as though they lived on opposite sides of the globe.”[33] The residents of Washington were described as “those who keep congress boarders and their mutual friends, the subordinate officers of government…. the labouring class… what may be called the better sort; and…the free negroes.”[34] McLeod must have seen the potential for growth that was to become of Washington and selected the bustling Navy Yard as the location to open his school. The Navy Yard, the leading manufacturing site in Washington City during this period, thrived with the construction and repair of America’s military warships (Figure 11).[35] This was a prime location to establish an academy for educating the children of tradesmen.

THE NAVY YARD SCHOOL (1808-1812)

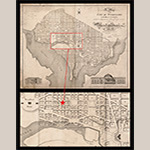

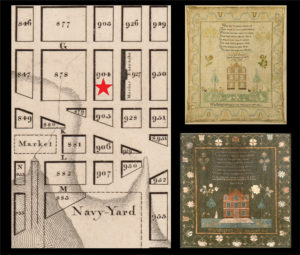

In May 1808, McLeod purchased property from Washington merchant Alexander Cochrane on Lot 904 across from the Marine Barracks (Figure 12).[36] Advertisements in both 1811 and 1812 refer to his home and place of work as “school rooms near the Navy Yard.”[37] Additional documentation helps to pinpoint this location. On 3 June 1810, the Baptist church met for their first few months in “the schoolrooms of John McLeod, on the west side of 8th street, a short distance north of I street, and opposite the Marine Barracks.”[38]

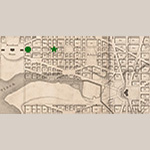

The earliest Navy Yard sampler – Julia Ann Crowley’s 1810 work – is the only one inscribed “Washington Navy Yard” (Fig. 9). Julia Ann (1799-c. 1833) was the daughter of ship carpenter Timothy Crowley who was employed at the Navy Yard and lived on 11th Street East near the Navy Yard Bridge (Figure 13).[39] Julia Ann married Thomas Fitten on 28 June 1820. [40] Thomas was, like Julia’s father, also a ship carpenter who lived near the Navy Yard.[41]

On 4 June 1812 Julia O’Brien (1800-1866) completed her sampler (Fig. 7) just weeks before the advertised year-end examinations at Mr. McLeod’s school which were held on 20 June at the same school rooms near the Navy Yard.[42] Her father, Michael O’Brien, worked at the Navy Yard as a turner and lived nearby on I Street South and 11th Street East (Figure 14).[43] In 1820, Julia married an Italian immigrant named Antonio Catalano who worked as a carpenter and joiner.[44] Julia and her husband Antonio lived near the Navy Yard for their entire lives.

The Crowley and O’Brien samplers (see Fig. 9 and Fig. 7) share similar characteristics and establish many of the criteria that make up this sampler group. The overall composition of these samplers is reminiscent of schoolgirl needlework coming out of Philadelphia during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (For Philadelphia examples, see Figure 15 and 16). Described by Betty Ring as “samplers with mansions and terraced gardens,” in both samplers a triple-peaked building is surrounded by a bucolic landscape scattered with animals and figures.[45] Decorative urns of flowers and floating flower sprigs delicately surround the chosen verse. In both samplers, hymns are stitched to profess their faith and the work is bound by an undulating floral border.

THE EASTERN ACADEMY (1812-1814)

In 1812 McLeod spent $6,000 on the construction of a new school building which he named the Eastern Academy.[46] After the June examinations that year, he moved into the new building. It was located on block 902 E Street between 7th and 8th Streets, only two blocks from his previous schoolrooms (Figure 17).[47] McLeod later described this school as “a beautiful establishment, and in high estimation in 1814… It was the only decent school-room in Washington.”[48]

Five known samplers that were produced during the Eastern Academy period survive: one dated 1812, three dated 1813, and one dated 1814. They include those worked by Maria Boswell (Fig. 6), Martha Ensey (Fig. 4), Julia Ann Crowley (Fig. 5), Charlotte Clubb (Fig. 8), and Catherine Cassady (Figure 18).

Maria Boswell’s 1812 sampler is the first known sampler from the group to feature a building with a bell tower (Fig. 6). Maria (1800-1868) was the daughter of Clement Boswell and Eleanor Collard Boswell. The Boswells and Collards were carpenters and builders and active on the city council.[49] Clement Boswell was a founding member of the Baptist church that met at the Navy Yard, in Mr. McLeod’s first schoolrooms.[50] Ten years after Maria finished her sampler, the 1822 Washington City directory listed her father Clement as a councilman living at the corner of 1st Street East and O Street South (Figure 19).[51]

In April 1813, two additional samplers featuring the same architectural motif of the bell-towered building were stitched by Martha Ensey and Julia Ann Crowley (the same Julia Ann Crowley who stitched the 1810 sampler). With the discovery of these samplers, Elisabeth Garrett was the first scholar to theorize that the building stitched on the Ensey and Crowley samplers represented an actual schoolhouse.[52] It is indeed compelling that the three samplers that feature this specific edifice of a brick building with a bell tower (Figure 20) all fall within the short two-year period between 1812 and 1814 when Mr. McLeod was teaching out of Eastern Academy.[53] Gloria Allen agreed with Garrett that these samplers could be representations of McLeod’s new Eastern Academy and added “it is possible that Maria’s [Boswell] sampler provides an image of this new and impressive building.”[54]

The 1822 Directory places the Ensey household just four blocks from the Eastern Academy (Figure 21).[55] Listed in the directory on the same block as William Ensey was John Jenkins, a dry goods merchant.[56] John Jenkins and Martha Ensey (b. 1803) were married on 22 February 1821 by Reverend McCormick at Christ Church near the Navy Yard.[57]

The 1813 Charlotte Clubb sampler (Fig. 8) does not include the bell-towered school, but it evokes the earlier style building with a triple pediment. Charlotte Clubb (1801-1846) and her family were living near the Navy Yard at the time of the 1820 census.[58] Charlotte never married and is buried at the Congressional Cemetery next to her brother John L. Clubb and her mother Elizabeth Clubb (d. 1851).[59]

In February 1814, Catherine Cassady (c. 1804-1827) stitched her architectural sampler which is part of a sub-group Gloria Allen named the “Stepped Terraces” group (Fig. 18).[60] While still incorporating the consistent composition seen in the other samplers, Catherine’s work is distinguished by a prominent terraced landscape emanating from her triple pedimented building. This stepped landscape is bordered by trees and full of grazing sheep. Catherine’s father, Nicholas Cassady, was a shoemaker living in the Navy Yard on 8th Street East, opposite the Marine Barracks, two blocks from the Eastern Academy (Figure 22).[61]

In 1812 conflict between the United States and Great Britain over maritime rights escalated into war. By 1814, the British set their eyes on Washington, DC, as the War of 1812 progressed. Eastern Academy was in a precarious position in its location not far from the prominent Navy Yard. As McLeod remembered, “When the enemy was approaching the City, I dismissed one hundred and seventy-two scholars from it [the school].”[62] In August 1814, war reached Washington and much of the city was destroyed by fire including the Navy Yard and numerous important public buildings, including the White House and the Capitol (Figure 23); however, it appears the Eastern Academy was spared.[63] Soon after the war, John McLeod sold the building which continued as a school for many years until it fell into disrepair.[64]

THE CENTRAL ACADEMY – CAPITOL HILL SAMPLER GROUP (1817-1835)

Washington experienced a massive surge of construction after the war’s devastating fire. The city’s vitality shifted from the construction at the Navy Yard to a political resurgence and rebuilding of Capitol Hill. Capitalizing on this shift and harnessing its momentum, McLeod invested $12,000 in the building of his next school, Central Academy. Having leased land with an option to purchase from the influential Washington politician John P. Van Ness, he strategically positioned himself between the newly reconstructed White House and Capitol Building. The school occupied lots 9, 10, and 11 of Square 346 and the property extended along G Street 100 feet and on 10th Street 138 feet (Figure 24). His new school building included an adjoining residence.[65]

In December 1817, Central Academy was “completely finished, and in neatness, order, and convenience, surpasses any establishment of its size in the union.”[66] John assured the public that the same “order, energy and attentions, which have characterized his conduct these ten years, in the two literary establishments which he has erected in this city” would continue at his new school, and he declared the motto of Central Academy as “Order is Heaven’s First Law.”[67] Here he continued to flourish.

Four years after he took up residence in his new school, in August 1821, McLeod announced his intention to expand his already successful school, specifically the Female Academy. He explained that “the female department of his present establishment with three rooms in his dwelling house, will afford complete accommodation for seventy young ladies until his new building shall be finished.”[68] In addition, he advertised for “a single lady, of decent deportment and amiable disposition, completely qualified to instruct young ladies in plain and ornamental needle work.”[69] Seven months later in 1822 he advertised that he would be building a second building on the premises, the Female Central Academy of Washington, which he said “will be elegantly finished.”[70] The entire school was quite large, accommodating 300 scholars, 150 of each sex.[71] With equal emphasis on female education at the Central Academy, Mr. McLeod assured that daughters would be instructed in the “useful and ornamental branches of education” including plain and ornamental needlework.[72]

In the eighteen years that Central Academy was open, six of the surviving “Navy Yard” samplers can be traced to the Academy, including the 1825 sampler by Mary Tait in the MESDA Collection (Fig. 2). In fact, this shift allows us to more accurately label the 1823-1828 samplers as the Capitol Hill Group.

Mary Tait and her family appear to embody the demographic profile of students represented in the Navy Yard and Capitol Hill Sampler Groups. At the Navy Yard, Julia Ann Crowley’s father was a ship carpenter, Julia O’Brien’s father was a turner and block maker, Maria Boswell’s father was in construction, and Martha Ensey’s father was a tailor. These trades were supported by the Navy Yard prior to the burning of Washington in 1814. After McLeod relocated his school closer to Capitol Hill, the fathers of the sampler makers of this later group were employed in trades supporting the rebuilding of the Capitol and government buildings; Mary Ann Bonthron, Margaret Simmons, and Mary Tait’s fathers were all stonecutters. This demographic stability may not be a coincidence.

McLeod was committed to the education of tradesmen’s children. Unlike other educators of the period, McLeod purposefully sought to educate children of the mechanic class. In 1822 he advertised in the National Intelligencer:

“Mechanics of every description may have their sons and daughters educated at this establishment without paying money. Trade will be taken from brickmakers, bricklayers, carpenters, stone cutters, plasterers, painters, blacksmiths, silversmiths, tinners, cabinetmakers, chairmakers, bookbinders, butchers, bakers, weavers, tailors, shoemakers, hatters, chandlers, &c.”[73]

This exchange of free tuition for mechanics’ daughters fulfilled McLeod’s mission of education “to all classes of the community” and in return he received free repairs to his schoolhouse.[74]

Living on the same block as Mary Tait, Mary Ann “Eliza” Thompson (1809-1896) was the daughter of James Thompson. The Thompson family lived on the east side of New Jersey Avenue between B and C Street South, at Capitol Hill (Figure 25). James Thompson was a grocer and Scottish immigrant.[75] Mary Ann Eliza stitched her sampler in 1823 (Figure 26), two years prior to Mary Tait’s.

Nine-year-old Margaret Simmons stitched her architectural sampler in 1828 (Figure 27). Margaret (1819 – bef. 1850) was the daughter of stonecutter William Simmons and his wife Elizabeth.[76] The Simmons family lived on B Street North between 1st Street and 2nd Street East, Capitol Hill (Figure 28).[77] Margaret married Patrick Dowling, a stonecutter like her father, in 1839.[78] It is unclear when Margaret died; however, the 1850 census shows Patrick Dowling and their children living with his mother-in-law Elizabeth Simmons, which suggests that she likely died prior to 1850.[79]

The recently discovered sampler worked by Mary Ann Bonthron (Fig. 10) fits snugly within this group. Like Mary Tait and Margaret Simmons, Mary Ann Bonthron (1816-1905) was the daughter of a Scottish immigrant stonecutter.[80] John Bonthron (1788-1835), Mary Ann’s father, is listed in the 1822 Washington Directory as living on 2nd Street West between F Street and G Street North, seven blocks from the Central Academy (Figure 29).[81] Mary Ann’s 1825 sampler depicts the same yellow house with closed shutters and angular trees with birds found on Mary Tait’s work (Figure 30).

Two other samplers round out this group and fall within the Central Academy period. Both samplers pose questions about their makers’ identity. Margaret Cassedy’s 1826 sampler (Figure 31) evokes design elements similar to those in Catherine Cassady’s earlier work from 1814. However, Margaret’s familial relationship to Catherine Cassady has eluded researchers thus far.

The second sampler is attributed to Amelia James (Figure 32).[82] Amelia may have been the daughter of Elizabeth James who is listed in the 1822 Directory living just three blocks from the Central Academy (Figure 33).[83]

JOHN McLEOD – ABOLITIONIST AND HUMANITARIAN

The nation’s capital and the region surrounding it had the largest population of freedmen in the United States thus producing an active environment for abolitionists.[84] In 1820, the Washington City census reported only 150 more enslaved men than free men of color. By 1840 the number of freedmen had jumped to 4,800 while the number of enslaved had fallen to 1,700.[85]

In the 1820s, McLeod began using his Central Academy to hold local Abolition Society meetings including the African Slave Abolition Society and the Abolition Society of Washington DC.[86] In March 1828, he endorsed the “Memorial of Inhabitants of the District of Columbia, Praying for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in the District of Columbia” that was submitted to the House of Representatives.[87] A year later he was listed as a member of the “Washington City Anti-Slavery Society.”[88] By the late 1820’s the abolitionist movement was intensifying in Washington, fueled by the large population of freedmen and active members such as McLeod.

As early as 1822, educational opportunities in Washington for freedmen’s children were growing as well. The Smother’s School (which later went under the names Columbian Institute and Union Seminary) were supported by the community including McLeod who was a “warm friend of the institution.”[89] The Hays’s School, which operated in the 1840s, was led by the formerly enslaved Alexander Hays and his wife Matilda, and McLeod was known to offer encouragement and to assist in their classrooms on occasion.[90]

McLeod’s influence extended beyond the classrooms and into the community. Perhaps because he was an immigrant himself, he dedicated much of his time to the relief of the many poor and impoverished Irish workers in the city. In 1830, under his leadership, the Washington Relief Society was formed.[91] Margaret Bayard Smith described the Irish laborers in Washington as “crowded into wretched cabins, where in some cases they have been found without bedding, seats, or tables – literally lying, sitting and eating on the floor…. working in the midst of disease.”[92]

McLeod did not shy away from educating Washington’s privileged either. Henry Clay, the Kentucky statesman who served as Secretary of State in the administration of John Quincy Adams, paid tuition in 1825 for his son James Brown Clay who was enrolled as a student at Central Academy.[93] Thirteen years earlier eight students from the male and female academy were listed in the National Intelligencer inviting members of the Senate and House of Representatives to their public examinations. These students included Verlinda Burch, the daughter of Captain Benjamin Burch, who later became the doorkeeper of the House of Representatives; Clifton Wharton, son of Colonel Franklin Wharton the Commandant of the Marine Corps; and Evelina McLain, daughter of Isaac McLain a noted architect in Washington City.[94]

COLUMBIAN ACADEMY – (1835-1846)

McLeod’s final school – the Columbian Academy – was established in 1835 and was where he taught alongside “an able corps of assistant teachers” until his death in 1846.[95] Only a couple of blocks away from his former Central Academy, the Columbian Academy, encompassing nearly 14,000 square feet, was his crowning achievement. It was located on 9th Street between G and H streets and was described as one of the most beautiful spaces in Washington (Figure 34).[96] This academy was on the same square the Fourth Presbyterian Church, bordered to the North by the Episcopal Church of the Ascension and St Patrick’s Church was on the adjoining square. The Patent Office was only a block to the south.

Only one sampler has been identified from this era: Mary Christeen Bohlayer’s 1842 sampler (Figure 35). This work is a bit of an outlier from the overall group. The Bohlayers lived near the Navy Yard, and it is likely that Mary Christeen (1828-1867) did not attend McLeod’s Columbian Academy, which was near the Capitol.[97] Although this sampler continues the compositional organization already established in this sampler group with its inclusion of a central architectural building with decorative urns and flowers, an undulating floral border, and a stepped terrace with animals, it is possible that this work, stitched fourteen years after that last documented sampler by Margaret Simmons, was produced at another school near her home at the Navy Yard. Could a former teacher or pupil from one of McLeod‘s academies teaching in the vicinity of the Navy Yard have instructed Mary Christeen in the making of her sampler? This could explain the similarity in the distinctive style and organization of her sampler to the overall group as well as offer an explanation as to the relative distance between the Bohlayers and McLeod’s Columbian Academy.

CONCLUSION

Five years before his death, McLeod reflected on his long career and noted that he had spent more than $20,000 building his schools and had sacrificed much to adhere to his motto “order is heaven’s first law.” However, he also stated that he was glad to boast that he had under his direction “more pupils than any other teacher in the Union.”[98] Having initially established himself at the Navy Yard, John McLeod‘s school quickly became a large and thriving source of educational opportunities for the craftsmen’s children of Washington City. Here immigrant craftsmen could provide education for not only their sons, but their daughters, all at no cost for trade in kind. As his school expanded, he occupied four distinct spaces, the Navy Yard Academy, Eastern Academy, Central Academy, and his Columbian Academy.[99]

This article has argued that the Washington Navy Yard sampler group can be attributed to John McLeod’s academies and that the three distinct sub-groups identified by Gloria Allen map directly onto the dates when John operated out of each distinct physical space. The varying characteristics – or distinct styles – represent the ever-changing staff that was required to run a large school over a long period of time as well as the changes in physical location. With regards to the visual connections of samplers stitched in Philadelphia – could McLeod’s wife, Rebecca Coulson McLeod, whose family was from Pennsylvania, be responsible for the connection and possible Philadelphia influence? While there is still more work to be done on this remarkable group of samplers, it seems clear that they were all stitched by working class girls at McLeod’s four schools between the years of 1810 and 1846. The Washington Navy Yard Group is one of the best-known groupings of American needlework. Being able to link it to McLeod’s schools not only provides an answer to one of the most pressing questions regarding the group but may open a number of avenues for further study.

APPENDIX: McLeod’s schools and the known samplers produced at each location

Navy Yard Academy (1808-1812)

Eastern Academy (1812-1814)

Central Academy (1817-1835)

Jenny Garwood is Assistant Collections Manager & Adjunct Curator of Textiles. She can be reached at [email protected]

The author wishes to express her heartfelt thanks to Anna Marie and David Witmer, the previous stewards of the sampler stitched by Mary Tait. Their generous friendship with MESDA made possible this important acquisition and research. The author also wishes to extend her deep appreciation to Robert Leath for his invaluable assistance, support, and mentorship, without whom this article would not have been possible.

[1] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 28 December 1846.

[2] Whig Standard, Washington, DC, 20 May 1844.

[3] William Bensing Webb and John Wooldridge, Centennial History of the City of Washington, D.C., With Full Outline of the Natural Advantages, Accounts of the Indian Tribes, Selection of the Site, Founding of the City … to the Present Time, ed. Harvey W. Crew (Dayton, Ohio: United Brethren Publishing House, 1892), 471-473. Online: https://archive.org/details/centennialhistor00crew/page/470/mode/2up (accessed 11 July 2024).

[4] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 20 January 1827.

[5] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 14 March 1822; 27 September 1823.

[6] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 14 March 1822.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Gloria Seaman Allen, Columbia’s Daughters Girlhood Embroidery from the District of Columbia (Baltimore: Chesapeake Book Company, 2012).

[12] Scotland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950 [database online]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014.

[13] The Washington Directory, 1822, 75. Online: https://archive.org/details/mdu-ill-060011/page/n83/mode/2up (accessed 11 July 2024).

[14] Evening Star, Washington, DC, 15 May 1895.

[15] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 24 March 1841; 1850 United States Federal Census.

[16] 1860 United States Federal Census.

[17] Evening Star, Washington, DC, 15 May 1895; Washington City Directory, 1822, 75. Online: https://archive.org/details/mdu-ill-060011/page/n83/mode/2up?view=theater (accessed 11 July 2024).

[18] Elizabeth Garrett, “American Samplers and Needlework Pictures in the DAR Museum,” The Magazine ANTIQUES, April 1975: 694-695.

[19] Betty Ring, Girlhood Embroidery (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), 528-531.

[20] Ibid., 530.

[21] Allen, Columbia’s Daughters, 167-188.

[22] Ibid., 187.

[23] Ibid., 224-249. This book also included a comprehensive appendix of all teachers and schools offering needlework instruction in the District of Columbia known at the time of publication.

[24] Scotland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014; The Washington Directory, 1822, 21. Online: https://archive.org/details/mdu-ill-060011/page/n29/mode/2up (accessed 11 July 2024). The surname Bonthron is spelled multiple ways in the records. The 1822 directory lists the surname as Bunthron. The author is using the spelling Bonthron as that is how Mary Ann stitched it on her sampler.

[25] Allen, Columbia’s Daughters, Appendix II, 231-249.

[26] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 30 August 1821.

[27] William Bensing Webb and John Woolridge, Centennial History of the City of Washington, D.C., With Full Outline of the Natural Advantages, Accounts of the Indian Tribes, Selection of the Site, Founding of the City … to the Present Time”, ed. Harvey W. Crew (Dayton, Ohio: United Brethren Publishing House, 1892), 471-473. Online: https://archive.org/details/centennialhistor00crew/page/470/mode/2up (accessed 11 July 2024); The Evening Star, Washington, DC, 22 May 1900.

[28] Evening Star, Washington, DC, 3 July 1900. Fifty-four years after John McLeod’s death, this letter to the editor was written by McLeod’s grandchild in response to a previous article which this writer claimed contained inaccuracies about McLeod. The grandchild wanted to set the record straight about McLeod’s devotion to the cause of education.

[29] Ibid; Maryland, U.S., Compiled Marriages, 1655-1850,” Ancestry.com. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/149508:7846?tid=&pid=&queryId=019693ef1c5a939f87781a932b41e0fb&_phsrc=ovx3&_phstart=successSource (accessed 1 May 2024).

[30] Evening Star, Washington, DC, 3 July 1900.

[31] Christ Presbyterian Church records, Adams County, Pennsylvania, 1777,” Ancestry.com. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/2473448:2451 (accessed 1 May 2024); Pennsylvania Veterans Card Files for William Coulson, 1780-1783, Monaghan, PA, Pennsylvania States Archives; Harrisburg, PA; Militia Officers Index Cards, 1775-1800, Series Number 13.36. Ancestry.com. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/159885:62200?tid=&pid=&queryid=d9a733f7-2baf-4742-a5ce-3eb1f7592117&_phsrc=LmU1106&_phstart=successSource (accessed 30 August 2024);1786 Septennial Census, York County, Pennsylvania, Ancestry.com. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/444369:2702 (accessed 1 May 2024); 1790 United States Census, Ancestry.com. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/356278:5058 (accessed 1 May 2024).

[32] Documented in the MESDA Craftsman Database are 158 entries for needlework teachers who operated schools in partnership with their spouses. Advanced MESDA Craftsman Database search conducted by Kim May, Director of MESDA Research and shared with author on 11 July 2024.

[33] Anne Newport Royall, Sketches of History, Life, and Manners in the United States, (New Haven, 1826), 155. Online: https://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbtn.18960/?sp=149&st=image (accessed 12 July 2024).

[34] Ibid.

[35] Charles William Jansen, The Stranger in America, 1793-1806, reprinted from the 1807 London edition (New York: The Press of the Pioneers, 1935), 208. Online: https://archive.org/details/strangerinameric00injans/page/208/mode/2up (accessed 12 July 2024).

[36] The National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser, Washington, DC, 23 October 1809.

[37] The National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser, Washington, DC, 8 August 1811; 18 June 1812; 14 December 1812.

[38] Wilhelmus Bogart Bryan, A History of the National Capital from its Foundation Through the Period of the Adoption of the Organic Act. (New York: The McMillan Company, 1914), 1: 604-605.

[39] The Washington Directory, 1822, 28. Online: https://archive.org/details/mdu-ill-060011/page/n35/mode/2up (accessed 12 July 2024).

[40] District of Columbia, U.S., Compiled Marriages, 1801-1825 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 1997. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/8581:2084?tid=&pid=&queryId=f5be3f67e314452146782296e4f3517f&_phsrc=fYL1&_phstart=successSource (accessed 12 July 2024).

[41] The Washington Directory, 1822, 35. Online: https://archive.org/details/mdu-ill-060011/page/n43/mode/2up (accessed 12 July 2024).

[42] The National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser, Washington, DC, 18 June 1812.

[43]The Washington Directory, 1822, 62. Online: https://archive.org/details/mdu-ill-060011/page/n69/mode/2up (accessed 12 July 2024).

[44] New York Herald, 8 January 1846. Arriving in Washington in 1817, Antonio Catalano was the son of the hero Salvadore Catalono who was rewarded the position of sailing master in the US Navy after bravely volunteering to pilot the Navy ship “Decatur” into the harbor at Tripoli and successfully setting fire to the American frigate “Philadelphia” which had been captured by pirates.

[45] Ring, Girlhood Embroidery, 361-369.

[46] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 20 January 1827.

[47] Wilhelmus Bogart Bryan, A History of the National Capital: from its Foundation Through the Period of the Adoption of the Organic Act. (New York: The McMillan Company, 1916), 2: 204. Online:https://archive.org/details/ahistorynationa00bryagoog/page/204/mode/2up?q=McLeod (accessed 1 May 2024).

[48]Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 20 January 1827.

[49] The Evening Star, Washington, DC, 26 February 1910.

[50] Washington Evening Star, Washington, DC, 4 January 1947.

[51] The Washington Directory, 1822, xix. Online: https://archive.org/details/mdu-ill-060011/page/n19/mode/2up (accessed 12 July 2024).

[52] “American Samplers and Needlework Pictures in the DAR Museum,” The Magazine ANTIQUES, April 1975, 694-695.

[53] The bell-towered samplers of Maria Boswell and Julia Ann Crowley are stitched on a dyed linen ground, while Martha Ensey’s sampler is worked on natural linen.

[54] Allen, Columbia’s Daughters, 177.

[55] The Washington Directory, 1822, 34. Online: https://archive.org/details/mdu-ill-060011/page/n41/mode/2up (accessed 14 July 2024). The residence is listed at n side Ls btw 7 & 8e, Navy Yard.”

[56] Ibid., 47. Online: https://archive.org/details/mdu-ill-060011/page/n55/mode/2up (accessed 14 July 2024).

[57] Daily National Intelligencer and Washington Express, Washington, DC, 26 February 1821, 3.

[58] 1820 United States Federal Census, Washington, DC, Ward 5. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/660211:7734?_phsrc=ABa9&_phstart=successSource&gsln=Clubb&ml_rpos=1&queryId=6fc60800296f8fbc84eb7714442af040 (accessed 14 July 2024). Listed on the same page of the census a few households before Elizabeth Clubb is Clement Boswell, Maria Boswell’s father.

[59] “Charlotte Clubb,” Find a Grave.com. Online: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/118252232/charlotte-clubb (accessed 1 May 2024).

[60] Allen, Columbia’s Daughters, 177.

[61] The Washington Directory, 1822, 24. Online: https://archive.org/details/mdu-ill-060011/page/n31/mode/2up (accessed 14 July 2024).

[62] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 20 January 1827.

[63] Library of Congress, “British Troops Land in Maryland on the Way to Burn Washington,” Today in History, August 19. Online: https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/august-19/ (accessed 29 January 2024); Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 20 January 1827.

[64] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 20 January 1827.

[65] Wilhelmus Bogart Bryan, A History of the National Capitol from Its Foundation through the Period of the Adoption of the Organic Act, Vol. II, 1815-1878, (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1916), 206.

[66] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 27 December 1817.

[67] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 21 September 1819.

[68] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 30 August 1821.

[69] Ibid.

[70] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 14 March 1822.

[71] McLeod’s school appears to have been comparatively large for the period. Publisher Jonathan Elliot in his Historical Sketches of the Ten Miles Square Forming the District of Columbia: With a Picture of Washington. . . (Washington, DC: J. Elliot Jr, 1830), 256, informs readers that there were two public free schools in Washington, DC, in 1830, which served a total of about 400 students. While McLeod occasionally advertised boarding for a few young ladies, costs for boarding were billed separately and did not appear to have factored in his trade in kind deal for mechanics. Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 14 March 1822.

[72] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 14 March 1822.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Constance McLaughlin Green, Washington: A History of the Capital, 1800-1950 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 93.

[75] The Washington Directory, 1822, 75-76. Online: https://archive.org/details/mdu-ill-060011/page/n83/mode/2up (accessed 1 February 2024).

[76] William Simmons married Elizabeth Shaw on 25 June 1817 in the District of Columbia. District of Columbia, U.S., Marriage Records, 1810-1953 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/153837:61404 (accessed 15 July 2024).

[77] The Washington Directory, 1822, 71. Online: https://archive.org/details/mdu-ill-060011/page/n79/mode/2up (accessed 1 February 2024).

[78] “District of Columbia Marriages, 1811 -1950,” Family Search. Online: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VNT9-CNY (accessed 15 July 2024). Entry for Patrick Dowling and Margaret Simmons, 09 May 1839.

[79] 1850 United States Federal Census, Washington, DC, Ward 3. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/19376498:8054?tid=&pid=&queryId=36caf68d-9b8a-4527-a5e6-c14ad1833339&_phsrc=LRp34&_phstart=successSource (accessed 15 July 2024). Another sampler worked by Margaret Simmons may also be attributed to John McLeod’s Central Academy. Stitched in 1827, the year before her architectural sampler, it is devoid of architectural motifs and bears a simpler form with alphabet bands, urns of flowers, and strawberry baskets with downward facing leaves. It is likely related to the 1827 Maria Brightwell sampler. Featuring a more sophisticated border, reminiscent of those on the architectural samplers, Maria’s work includes alphabet bands, flowers in urns, and a variation of the strawberry basket. Maria Brightwell was the daughter of John L. Brightwell, who is listed in the 1822 Washington Directory as the Sexton of the Eastern Burial Ground with his home on Maryland Avenue near the toll-gate.

[80] Scotland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. John Bonthron married Grace Harper on 2 March 1822 in Washington, DC. District of Columbia, U.S., Compiled Marriages, 1801-1825 database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 1997. Online: https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/3923:2084?tid=&pid=&queryId=8ffba494-fb3f-4082-906f-396a8f144419&_phsrc=DWs5&_phstart=successSource (accessed 1 May 2024); Mary Ann and her stepmother Grace are listed as administrators for the personal estate of John Bonthron. Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 26 May 1836. John Bonthron’s tombstone reads “In Memory of John Bonthron a native of Scotland.” Online: www.findagrave.com/memorial/147440448 (accessed 15 July 2024).

[81] The Washington Directory, 1822, 21. Online: https://archive.org/details/mdu-ill-060011/page/n29/mode/2up (accessed 1 February 2024).

[82] Allen, Columbia’s Daughters,182-183. Significant thread loss makes it difficult to read the stitched name and date. The attribution is based on analysis by Gloria Allen.

[83] The Washington Directory, 1822, 47. Online: https://archive.org/details/mdu-ill-060011/page/n55/mode/2up (accessed 16 July 2024). She lived on the east side of 14th Street West between F Street & G Street North.

[84] Jeff Dickey, Empire of Mud: The Secret History of Washington, DC, (Lyons Press: Guilford, Connecticut, 2014), 88.

[85] Ibid, 87

[86] Washington National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 8 September 1827; 11 December 1828.

[87] William G. Thomas III, et al, editors. “Memorial of Inhabitants of the District of Columbia, Praying for the Gradual Abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia, March 24, 1828.” Online: https://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.supp.0004.001 (accessed 1 May 2024).

[88] Minutes of the Twenty-first Biennial American Convention for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and Improving the Condition of the African Race, convened at the city of Washington, December 8, A.D. 1829. . . (Philadelphia: Thomas B. Town, Pr., 1829), 4. Online: https://www.loc.gov/resource/lcrbmrp.t1505 (accessed 16 July 2024).

[89] Henry Barnard, ed., American Journal of Education, 1870: Vol. 19, (Hartford: F. C. Brownell, 1870), 200. Online: https://archive.org/details/sim_american-journal-of-education-1855_1870_19/page/200/mode/2up (accessed 16 July 2024).

[90] George W. Williams, History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880: Negroes as Slaves, as Soldiers and as Citizens, Together With a Preliminary Consideration of The Unity of The Human Family, an Historical Sketch of Africa, and an Account of The Negro Governments of Sierra Leone and Liberia, Volume 2 (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1883), 138.

[91] Constance McLaughlin Green, Washington: A History of the Capital, 1800-1950, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), 133.

[92] Margaret Bayard Smith and Gaillard Hunt, The first forty years of Washington society, portrayed by the family letters of Mrs. Samuel Harrison Smith (Margaret Bayard) from the collection of her grandson, J. Henley Smith, (New York, C. Scribner’s Sons, 1906), 335-336.

[93] Henry Clay, James F. Hopkins, and Mary W. M. Hargraves, The Papers of Henry Clay. Volume 4. Secretary of State, 1825 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2014).

[94] National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 18 June 1812.

[95] Evening Star, Washington, DC, 3 July 1900.

[96] Daily National Intelligencer, Washington, DC, 20 June 1845.

[97] Edward Waite, The Washington Directory and Congressional and executive record, for 1850 (Washington D.C.: Columbus Alexander, Printer, 1850), 9. Online: https://archive.org/details/washingtondirect00wait/page/n49/mode/2up?q=Bohlayer (accessed 1 May 2024); Daily National Intelligencer and Washington Express, Washington, DC, 27 May 1850. Mary Christeen was the daughter of butcher John Bohlayer (1794-1850) and his wife Ann. John Bohlayer’s obit records “his late residence, near the Navy Yard.”

[98] Harvey W. Crew, Centennial History of the City of Washington D.C. With Full Outline of the Natural Advantages, Accounts of the Indian Tribes, Selection of the Site, Founding of the City….to the Present Time, 1892. Online: https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_5Q81AAAAIAAJ/page/473/mode/2up?q=McLeod (accessed 1 May 2024).

[99] Although John McLeod occupied four distinct spaces throughout his career in Washington, this paper argues, that at this time, surviving samplers can only be attributed to three of his four schools – Navy Yard Academy, Eastern Academy, and Central Academy.